Aztec Art – Exploring the Most Influential Aztec Ancient Artworks

The Aztec civilization is part of the broader ancient Mesoamerican society of the 15th and 16th centuries based at Tenochtitlán, better recognized today as Mexico-Tenochtitlán. Mexico-Tenochtitlán was the capital of the Aztec empire, which is currently a historical city of Mexico City and the birthplace of some of the most intricate and profound artworks in history. In this article, we will examine the Aztec civilization and its art forms, including some of the most famous surviving examples of ancient Aztec paintings, sculptures, and objects. Read on for a comprehensive tour of the ancient art world of the Aztecs!

The Aztec Empire in Mesoamerica

Present-day Mexico City was built on the ancient ruins of a historical and influential city called Tenochtitlán. It was around 1325 CE when a Mesoamerican civilization called the Aztecs or Mexica people founded Tenochtitlán, which was established as the capital of the Aztec Empire. Legends state that the Mexica people were guided by a God named Huitzilopochtli to leave their homeland, Aztlan, and build a new life wherever they encountered a specific scene of an eagle devouring a snake while perched on a cactus.

This was how Tenochtitlán was founded. This region was called Anáhuac and was connected to five lakes. The largest lake was chosen as the site for the Aztecs to build their new city.

Aztec Coyolxauhqui, Moon Goddess (15th Century); Gary Todd, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Aztec Coyolxauhqui, Moon Goddess (15th Century); Gary Todd, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Aztec empire is also referred to as the Triple Alliance, which is short for the trio of allies between the Nahua city-states: Tetzcoco, Mexico-Tenochtitlán, and Tlacopan. The capital that dominated the Aztec empire rose to power militarily despite the alliance initially relying on self-governing systems. Many scholars describe the governance of the empire as “indirect” since they allowed rulers of cities, they conquered to remain in their positions on the condition that they paid a set amount to the alliance and offer up military labor when necessary.

The Aztecs offered their protection through military power and political stability, which made the empire somewhat of an effective form of imperial authority.

Some key cultural and religious factors that governed the lives of the Aztec empire included the worship of the rain God, Tlaloc, the God of the sun and war, Huitzilopochtli, and human sacrifices via bloodletting practiced at the Templo Mayor precinct (city center). The Aztec culture believed in numerous Gods and goddesses, each dedicated to a particular aspect of human function for survival or the elements of nature. In August 1521, the city was invaded by the Spanish and after rounds of looting and destruction, the capital was rebuilt and renamed Mexico City.

The Aztecs’ Art and Architecture

Among the other Mesoamerican societies such as the Olmec, Maya, Toltec, and many other Mesoamerican groups, the most common forms of art practiced during the 15th and 16th centuries include architecture, monumental sculpture, geometric shapes on stamps, decorative pottery, metalwork, and even body art. Symbols were incredibly important to Aztec society as they incorporated some of the culture’s most significant religious motifs involving themes such as fertility and agriculture, plants, deities, animals, and ceremonial processes.

Aztec Feather Shield (15th Century);Gary Todd, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Aztec Feather Shield (15th Century);Gary Todd, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

As in any diverse environment, Aztec artists were inspired by the productions of their neighbors such as the Oaxaca society, many of whom belonged to the culture and resided in the capital. Aztec art is considered the most eclectic and complex art from the ancient Mesoamerican era. Many surviving Aztec art drawings can also be seen on the remains of ancient architecture at sites such as the Templo Mayor of the Sun and Moon. The Aztecs’ art and architecture were embedded with a diverse array of symbols, from sea creatures and birds to conch shells and frogs.

The most common themes found in Aztec carvings on reliefs in architecture include symbols of fertility, Tlaloc symbols, the eagle as a symbol for warriors and the sun, and myriads of colorful paintings that once decorated the inner chambers of temples.

It is important to remember that the many Aztec Gods were of high value and importance to the Aztecs and they specifically built temples dedicated to certain Gods that would be decorated and embellished with the finest artworks. Aztec carvings on the stones of these temples would draw on astronomy, religion, and cosmology, and stressed the importance of the desire for sacrifice in service to their Gods. Below, we will explore some of the most famous examples of Aztec art across painting, sculpture, drawing, and carving.

The Aztecs’ Sculpture

The Aztecs’ sculptures are the best surviving art form from the society that sheds light on the lifestyle and religious beliefs that led them. Many sculptures attributed to the Aztec culture were carved out of wood or stone and were often monumental structures that held some sort of religious purpose.

The most common purpose of these monumental sculptures was that they served as idols for the Gods to inhabit.

The practice of bloodletting or offering up one’s blood for sacrificial purposes was connected with the sculpture as food offerings for the Gods alongside other precious jewels. Below, we will introduce you to some of the most fascinating sculptures from Aztec culture.

Vulture Vessel (c. 1200 – 1521)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1200 – 1521 |

| Medium | Ceramic |

| Dimensions (cm) | 21.3 x 21 x 23.2 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

Pottery and ceramics were incredibly popular art forms in Mesoamerican cultures, including the Aztecs. Ceramic vessels such as the Vulture Vessel are part of a genre of ceramics dedicated to animal effigies during the pre-Columbian era and were discovered across Mexico. The bird was a symbol of the celestial realm, including celestial objects such as the sun, moon, stars, and the planet Venus.

These colorful animal ceramics were often used in ceremonies and the animals selected for the ceremonies would have held a role in the myth enacted or narrated.

Vulture Vessel (c. 1200 – 1521); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Vulture Vessel (c. 1200 – 1521); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This vulture vessel is supported by a tripod base formed by the bird’s legs and tail. It is believed that the bird is the Sarcoramphus papa or the king vulture and was connected to human sacrificial ceremonies. The vulture’s talons are portrayed as human hands with enlarged thumbs and its head features a pleated fan-shaped headrest that mimics the headrests of many Aztec deities.

The surface is coated in a red and black pigment, which creates a striking contrast that echoes the significance of rituals such as human sacrifice in the Aztec culture.

The Stone of Tizoc (c. 1485)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1485 |

| Discovery Date | 17 December 1791 |

| Site of Discovery | Mexico City |

| Medium | Carved Basalt rock |

| Dimensions (cm) | 93 (h) x 265 (d) x 831 (c) |

| Where It Is Housed | National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico |

This massive circular sculpture portrays scenes of Aztec mythology combined with the politics of the culture at the time, dating back to the late 15th century. The sculpture is believed to have originally possessed a sacrificial function where human sacrifices were made on the stone itself. It is also believed that the victims of these sacrifices were most likely warriors defeated in battles.

The relief carvings around the sculpture portray Tizoc, an Aztec ruler, charging into battle against warriors from Matlatzinca.

Stone of Tizoc (c. 1485); Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Stone of Tizoc (c. 1485); Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The defeated parties are depicted as “landless barbarians”, referred to as Chichimecs, and the winning group is seen adorned in noble attire characteristic of ancient Toltec. The upper section of the sculpture is almost three meters wide and illustrates an eight-pointed sun disc. The top half also contains celestial symbols of the stars and Venus with multiple circular pieces of jade. The bottom half of the rim contains imagery representing a pre-Columbian deity called Tlaltecuhtli at each cardinal point. Separating the glyphs are images of sacrificial knives called tecpatl. The sculpture itself is said to be an instrument of propaganda for one of the Aztec emperors, Tizoc, who most likely commissioned the work as a nod to the multiple sites that the Mexica people conquered.

Other associations drawn to the meaning of the sculpture are identified as an acknowledgment of the Aztec tribute system where conquered cities were required to offer up sacrifices as a tribute to the current emperor as well as the Aztecs’ relationship with the divine.

Mosaic Skull of Tezcatlipoca (c. 15th – 16th Century)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 15th – 16th century |

| Medium | Turquoise, pyrite, pine, lignite, human bone, deerskin, conch shell, agave |

| Dimensions (cm) | 19 x 13.9 x 12.2 |

| Where It Is Housed | The British Museum, London, England |

Turquoise was a stone sent to the capital as a tribute to the Aztecs as part of the other city-states’ deal with the empire. This enigmatic turquoise encrusted skull represents a God called Tezcatlipoca, who was regarded as one of four powerful deities and one of the most important Gods to the Mexica.

The turquoise mosaic on the skull is a common characteristic of Aztec art that was used to decorate objects belonging to members of high nobility and priests, including objects dedicated to Gods.

Mosaic Skull of Tezcatlipoca (c. 15th – 16th Century);© Hans Hillewaert

Mosaic Skull of Tezcatlipoca (c. 15th – 16th Century);© Hans Hillewaert

Numerous human skulls were used as the base for such decorations in tribute to the Aztec Gods and included other materials such as shells and various precious gems. Additional sculptural inlays would be made to such objects to enhance the sculpture. Approximately 25 mosaic artifacts are housed in Europe with nine at the British Museum in London. Most of the surviving mosaics date to before the Spanish conquest in 1521 and are recorded in the colonial inventories of objects sent to Europe during this period.

Other well-preserved mosaics can be found in the United States and Mexico.

The Sun Stone (c. 1502 – 1521)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1502 – 1521 |

| Discovery Date | 17 December 1790 |

| Site of Discovery | Mexico City |

| Medium | Carved Basalt rock |

| Dimensions (cm) | 358 x 98 |

| Where It Is Housed | National Anthropology Museum, Mexico City, Mexico |

This is perhaps one of the most recognizable sculptures from Aztec art history that has fascinated many scholars since its rediscovery in 1790. It is believed to have been sculpted between 1502 and 1521 toward the end of the Mesoamerican Postclassical period and is also dubbed the Aztec Calendar Stone. The source of the rock from which the Sun Stone was sculpted was taken from the Xitle volcano, which is believed to originate from either San Ángel or Xochimilco.

It is believed that the rock was dragged by thousands of people across 22 kilometers to the center of the capital.

The Sun Stone (c. 1502 – 1521); Sasha Isachenko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Sun Stone (c. 1502 – 1521); Sasha Isachenko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to a report, the Archbishop of Mexico, Alonso de Montúfar, ordered the sculpture to be buried around the mid-15th century so that the memories associated with ancient sacrifices on that stone would be lost too. Scholars initially concluded that the stone was most likely used for chronology, astrology, or as a sundial, however, in an effort by various scholars to determine the actual meaning of the glyphs on the stone, it was discovered that the glyphs were representative of days in a month and that it was once painted in bright colors.

It was later established that the four symbols on the face of the stone were representative of the four past suns or eras. The four points may also allude to the four corners of the earth while the inner circles on the face could refer to space and time, but these are all theories.

Another theory that builds on the stone’s religious significance is that the face on the stone represents the deity of the sun, Tonatiuh and this is why the stone is called the “Sun Stone”. Other scholars identify the face as Tlaltecuhtli, who was a Mexica earth deity that was commonly found in many creation myths. Researchers from the National Anthropology Museum believe that the stone was a ceremonial basin or altar as opposed to a tool for astrological or astronomical purposes. The second most plausible function of the stone aside from its function as a sacrificial altar is that it carried political weight in terms of its placement and function as a symbol of authority.

Aztec Objects

The Aztec culture appreciated the ornamental and decorative nature of art, which can be seen in pottery and many ancient objects and artifacts. Below, you will find a few interesting and ornate Aztec objects that bring us closer to the lifestyle and preferences of the Aztecs.

Pectoral Ornament (c. 1200 to 1519); Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Pectoral Ornament (c. 1200 to 1519); Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Feathered Serpent Pendant (c. 14th – 16th Century)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 14th – 16th century |

| Medium | Shell |

| Dimensions (cm) | 4.4 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

This dainty yet remarkably detailed shell pendant is an ehecacozcatl or wind jewel, which is an ornament affiliated with the wind God Quetzalcoatl-Ehecatl. This minuscule pendant is carved with tender accuracy and is embedded with many meanings. The medium, shell, was a material associated with warriors, fertility, and water, and its importance was further associated with the Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl. These tiny ornaments were highly treasured in ancient times and were often produced in specialized shell workshops situated close to royal buildings.

The function of such pendants was linked to private ceremonial purposes for the Mexica elite and is a symbol of the control over access to raw materials and fine artworks that exude beauty, which was a privilege at the time.

The pendant still holds the original shape of a conch shell while its delicate incisions illustrate a feathered serpent and a coiled rattlesnake on opposing ends. In addition to the snakes are two human hands: one holding a knife and the other holding a plant called Philodendron affine (huacalxo ́ chitl), which was associated with pleasure and sensuality. The feathered snake pendant is so tiny yet it holds immense meaning. It is definitely an object to be admired. You can find images and more information here.

Frog Pendants From Ornamental Necklace (c. 15th – Early 16th Century)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 15th – early 16th century |

| Medium | Gold |

| Dimensions (cm) | 2.2 x 15.2 x 14 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

The Aztecs ascribed meaning to many animals, including the frog as seen in the necklace pendants above. Necklaces such as this were worn by the elite members of the Aztec society and were commonly decorated with beads shaped as shells, frogs, turtles, and other mini-gold animal figures. The frog is an amphibious creature associated with water, which is further affiliated with sustenance and fertility.

You can find pictures and more information here.

It is believed that these tiny frog pendants were cast using a long-lost wax process with a separate mold made out of clay for each pendant. The mold would then be broken after casting, which explains the varied sizes and appearance of each pendant. Talk about a highly customized, bespoke adornment!

These pendants were also made out of gold, which was attributed to another Mesoamerican culture known as the Mixtecs, who were recognized as the best craftsmen in all of Mesoamerica.

The Aztecs, of course, sought out the pleasures of fine workmanship and would have commissioned many ornamental objects. These gold pendants are currently still unclassified as either Aztec or Mixtec since there is uncertainty as to the true source.

Ancient Aztec Paintings and Drawings

Art and language were interconnected for the Aztec people of Central Mexico. Painting images as a language was so important to this culture that the Nahuatl word for a painter, tlacuilo directly translates to the English word painter-writer or painter-scribe.

This resulted in many manuscripts and books, which document the culture, lifestyle, and history of the Aztec civilization.

The Codex Mendoza is one such record that was commissioned by the first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, in 1541. The historical record was commissioned as part of a project to document any and all information about the Aztec people and system. The book contained information, mainly presented through glyphs, about the different rulers of Tenochtitlán, the tributes paid to the empire, and a detailed account of the life of the people each year.

Codex Mendoza (1541); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Codex Mendoza (1541); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The artists behind the glyphs and paintings were indigenous and the images were annotated by a priest who spoke the language of the Nahua people (Nahuatl). The codex was meant to be sent to Emperor Charles V (Spain) but it did not reach its intended destination. Instead, the codex was stolen by French pirates and moved to France. The codex resurfaced to the French public in the 16th century after being acquired by the cosmographer of King Henry II, André Thevet, who signed his name on a few pages in the book.

Below, we will examine a few ancient Aztec paintings that shed valuable insight into ancient Aztec paintings and drawings.

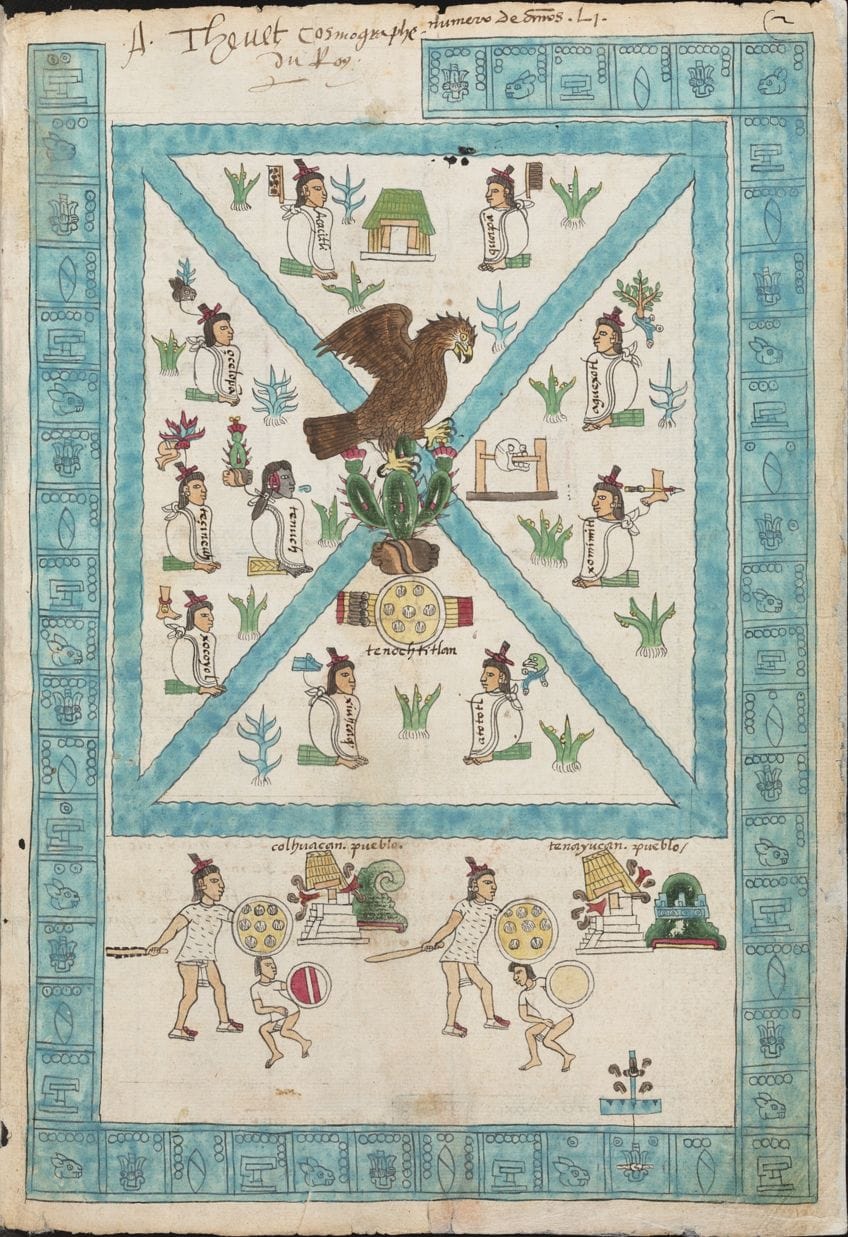

Frontispiece, Codex Mendoza (c. 1541 – 1542)

| Artist | Unknown indigenous artist |

| Date | c. 1541 – 1542 |

| Medium | Pigment on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 32.7 x 22.9 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Bodleian Library, Oxford, England |

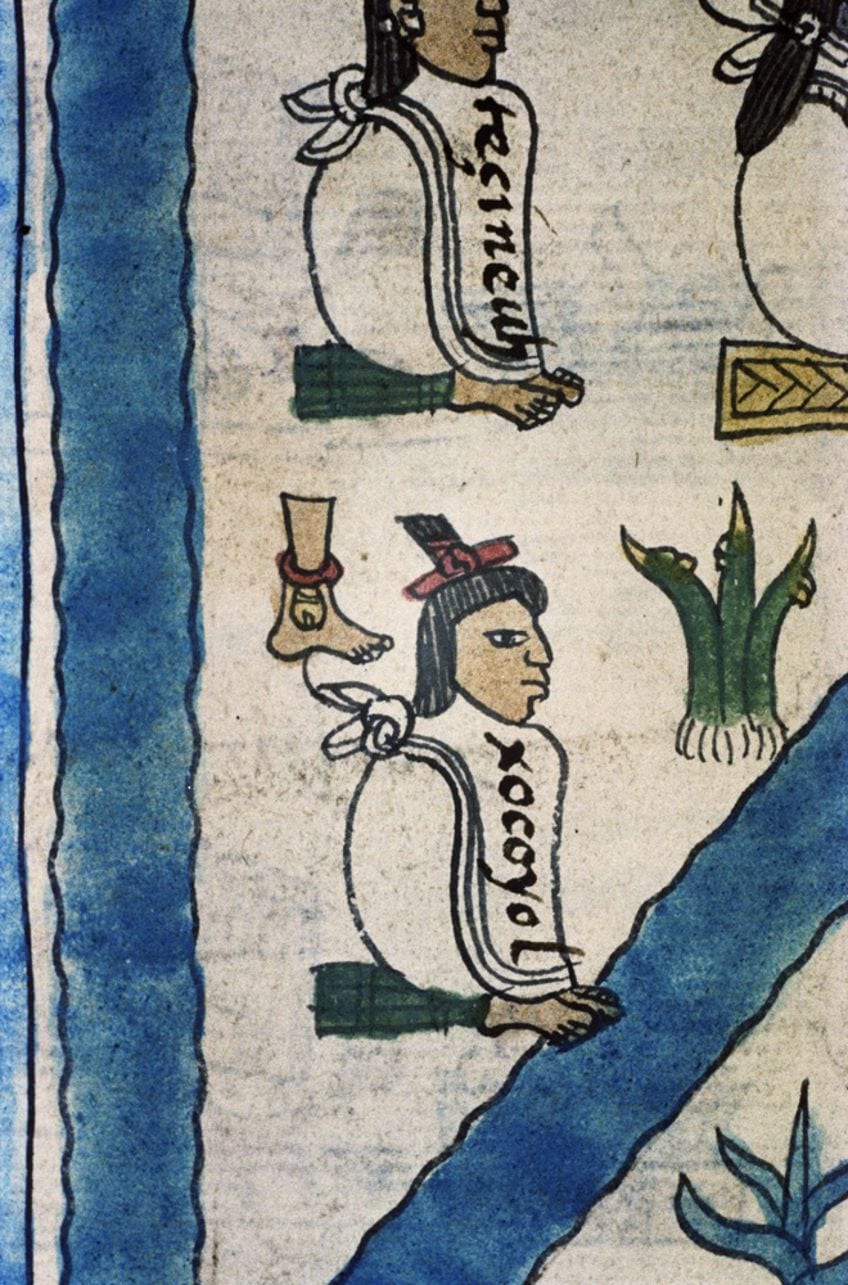

This is the first page of the Codex Mendoza, which illustrates the founding of Tenochtitlán. It is important to note that the book is divided into three sections: an Aztec chronicle listing the lords of the capital from 1325 to 1521, a list of 39 provinces with conquered towns amounting to 400 that were required to pay tributes, and the last section detailing the everyday life of the Aztec people.

This painting illustrates the discovery of Tenochtitlán in Lake Texcoco with the iconic imagery of the eagle perched on the cactus that is growing out of a stone.

Frontispiece, Codex Mendoza (c. 1541 – 1542); The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Frontispiece, Codex Mendoza (c. 1541 – 1542); The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There are multiple figures surrounding the eagle and each is said to be the 10 founders of Tenochtitlán. On the left of the eagle is the founder whose name was used for the city, Tenoch. This is perhaps one of the most significant ancient Aztec paintings that contain traces of generations of retelling and sharing of the narrative around Tenochtitlán. Although the codex is a post-conquest project, its artwork and symbolism convey the once-dynamic nature of the original Aztec culture. The artwork appears very organized, geometric, and pictorial.

One can immediately understand that the culture valued symbolism, order, a degree of sophisticated opulence, and space.

Ancient Aztec artists/scribes were intentional about the organization and presentation of narratives and story arcs. Some narratives include crowds of people in a single event while others highlight durational changes or the role of the environment in the story. The artists of the time were creative and story-telling was clearly a major influential factor in the art. The composition was more about communication and less about artistic enjoyment. Aztec art was a language.

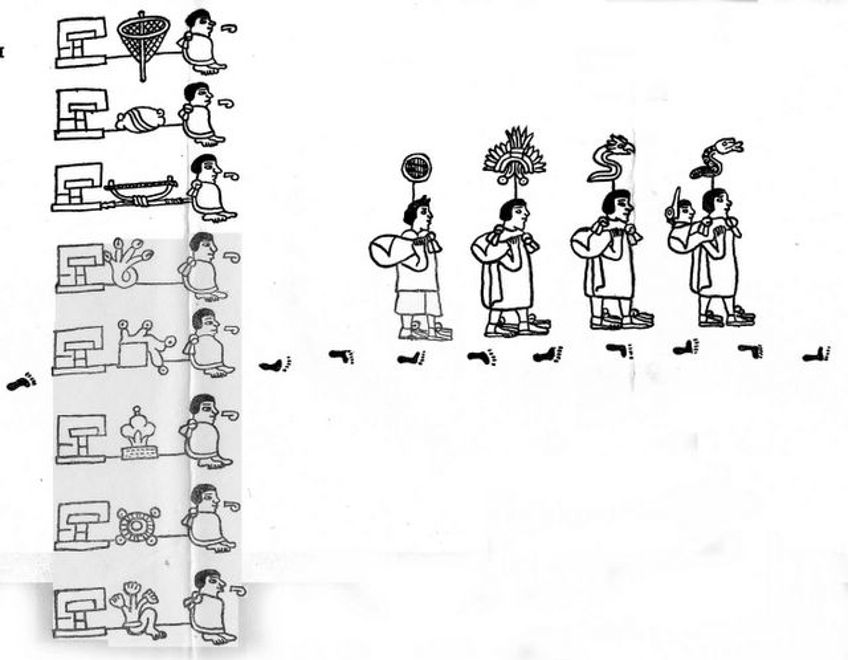

Folio 1, Tira de la Peregrinación de Los Mexica (Early 16th Century)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. early 16th century (either just before or immediately after the 1521 conquest) |

| Medium | Pigment on folded amate |

| Dimensions (cm) | 19.8 x 25.4 (Codex: 549 x 19.8) |

| Where It Is Housed | National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City, Mexico |

The Tira de la Peregrinación de Los Mexica “Tale of the Mexican Migration” or the Codex Boturini is another important historical document with Aztec drawings that document the migration of the Aztec people from their previous hometown, Aztlán, to Tenochtitlán. While the date of creation or artist is unknown, the Codex Boturini is said to have been created either just before the Spanish invaded Tenochtitlán or right after the invasion. The imagery from the codex has become an iconic symbol of the pilgrimage and heritage of the Aztec people and can be viewed at the entrance of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

The book earned its nickname Codex Boturini from an 18th-century collector called Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci who was also a historian and ethnographer of New Spain.

Folio 1, Tira de la Peregrinación de Los Mexica (Early 16th Century); AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Folio 1, Tira de la Peregrinación de Los Mexica (Early 16th Century); AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The book itself is quite uniquely shaped since it was made in an accordion format with indigenous paper. This format was considered conventional for pre-Hispanic books with paintings in Mexico. The first page as seen above illustrates the migration by showcasing a figure in a canoe that appears to depart an island on the lake. The artist highlights that this is an island by outlining the shore in a continuous wavy line. The image also shows a male and female figure with their profiles facing the direction of the canoe. The footprints on the parchment lead to an image of Colhuacan, which contains an image of the head of an Aztec deity called Huitzilopochtli.

A pile of curled scrolls appears from the deity’s head and represents the deity in conversation with the migrants, acting as a guide.

Other pages of the codex contain further scenes from the story of the Aztec migration, including a glyph showing their pit stops on the way and signs to indicate how many years they stayed in a particular location before moving. The artists were incredibly skilled at combining narrative with detail, accuracy, and visual imagery, of course. The artist(s) of this codex seemed to focus more on the chronological sequence of the journey as compared to the artist of the Codex Mendoza whose artwork carries more visual detail in terms of color and general symbolism.

Jaguar Fresco (c. 16th Century) at Tlatelolco

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 16th century |

| Medium | Pigment on a cave wall |

| Dimensions (cm) | Information Unavailable |

| Where It Is Housed | Caja de agua, Tlatelolco, Mexico City, Mexico |

The city of Tlatelolco was one of the rival city-states of Tenochtitlán, which was later integrated into the capital around 1473. Archaeologically, the city of Tlatelolco contained an impressive ceremonial complex that was equally as impressive as that of Tenochtitlán, however, around the time that this jaguar mural was painted, the Spanish conquest was afoot. This jaguar wall painting is one of its kind since it is one of the few remaining paintings of modern Aztec society, close to the civilization’s conquest and end of its reign.

The jaguar painting was discovered at Caja de Agua, which is a basin with water that runs from Chapultepec Hill.

Jaguar Fresco (c. 16th Century); Ymblanter, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Jaguar Fresco (c. 16th Century); Ymblanter, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Other Aztec art drawings found alongside the jaguar mural were once vividly colored but with time, have been subject to the forces of nature and erosion. This painting is considered a unique expression of both Spanish and Aztec-themed imagery depicting scenes of people fishing, canoes on lakes, frogs, jaguars, reeds, and snakes. Archaeologist Salvador Guilliem states that these murals demonstrate the encounter that the Europeans had with Mexican culture, made at the exact moment of the conquest. This is also perhaps one of the last ancient Aztec paintings to exist outside the destruction of the Spanish conquest yet at the same time coinciding with it.

Aztec art is multifaceted and loaded with rich artistic expertise that is difficult to pinpoint in Contemporary art forms. The intricacy, technical skill, and talent for story-telling across the Aztecs’ art and architecture is something to be marveled at. Religious beliefs and ceremonial practices played a huge role in defining the core tenets of Aztec artwork, which enveloped the lives of this ancient Mesoamerican civilization so much that it was a customary part of their existence and historical record. We hope that this overview of Aztec ancient art has enlightened you on the magnitude and breadth of this culture’s artistic oeuvre.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Main Themes in Aztec Artworks?

The main themes in Aztec artwork are religious themes and symbols associated with the worship of various Gods and deities. Common themes include the celebration of fertility, narrative scenes of Aztec history, everyday life, celestial objects, human sacrifice, and many animals with specific meanings attached to them.

Why Is Aztec Ancient Art Significant?

Aztec ancient art is significant because it provides visual information via glyphs, paintings, and drawings related to the heritage and culture of the Aztec culture, which forms a major part of Mesoamerican society before the Spanish conquest. It is a strong part of Mexican history that provides data on the belief systems, methods of governance, lifestyle, culture, and historical events of a pre-Columbian culture that once dominated many societies.

What Is the Most Famous Aztec Sculpture?

The most famous Aztec sculpture is considered to be the Sun Stone, otherwise referred to as the calendar stone. It is recognized as an important artifact and sculpture from the Aztec empire that was once located at the center of Tenochtitlán. The stone sculpture is estimated to date between the years 1502 and 1521, just before the Spanish Conquest.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.