Battle of Culloden – Death Knell for the Jacobean Revolt

When was the Battle of Culloden and who won the Battle of Culloden? The Culloden Battle took place on the 16th of April, 1746, and was an important conflict of the Jacobite uprising that began in 1745. The Battle of Culloden combatants comprised the Jacobites on the Scottish side, and the British government forces, who were led by the Duke of Cumberland. To learn more about the Scotland Battle of Culloden, read on below!

Contents

The History of the Battle of Culloden

| Name of Battle | Battle of Culloden |

| War Associated With | Jacobite Rising |

| Date Battle Began | 16 April 1746 |

| Date Battle Ended | 16 April 1746 |

| Location of Battle | Inverness, Scotland |

The Culloden Battle was the result of attempts by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the throne in Britain for the House of Stuart. The Jacobite army was substantially outnumbered, suffering the loss of around 1500 men, while only around 50 Royalist soldiers were killed. To better understand why the battle took place, let us begin with some background historical context.

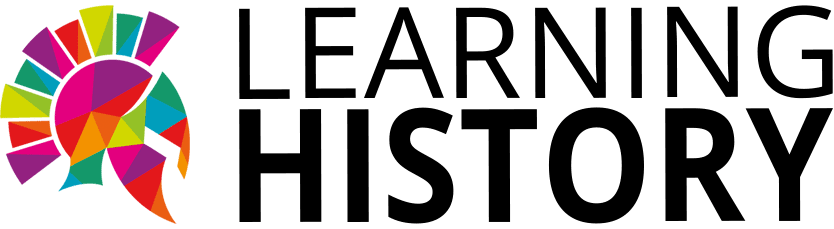

The Battle of Culloden by David Morier (between 1746–1765); David Morier (1705?–1770), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Culloden by David Morier (between 1746–1765); David Morier (1705?–1770), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Historical Context of the Scotland Battle of Culloden

The Roman Catholic monarch, King James II, was ousted by Parliament and a predominantly Protestant political society in 1688. His dictatorial conduct and the creation of a formidable standing army seemed to indicate the emergence of a totalitarian Catholic monarchy. Mary and Anne, James’s daughters from his first marriage, reigned after his passing. On the instructions of their uncle King Charles II, Mary and Anne were raised as Anglicans and Anne married her Dutch protestant cousin William III of Orange. The behavior of the Catholic James II had fueled longstanding fears. From the 16th century onwards, following Queen Mary I’s sometimes violent attempts to reverse her father Henry VIII’s and her brother Edward VI’s protestant reformations, the English parliament had regarded Catholic monarchs with apprehensive suspicion.

In 1714, when Queen Anne, despite 17 pregnancies, died without an heir, Parliament replaced the Stuarts with the German dynasty, the Hanoverians. The claims to the throne of James II’s son, the Catholic James Francis Edward, fell on deaf ears.

Anne Queen of Great Britain by Michael Dahl (1705); Michael Dahl, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Anne Queen of Great Britain by Michael Dahl (1705); Michael Dahl, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Causes of the Battle of Culloden

Before we get into the details of the battle, we shall first look at the various causes of the battle. This will enable you to better understand the motivations of the highland clans who fought in the battle. This includes the various political, ideological, and economic factors that resulted in the Jacobite uprising.

Political and Economic Factors

At the time, Scotland was divided politically between individuals who were in support of the British government versus those who favored the House of Stuart, Scotland’s historic governing family.

The Jacobites attempted to re-establish the Stuart dynasty in the British monarchy, which had been deposed in 1714 by the Hanoverians.

Many Highland Scots joined the Jacobite cause, believing that the Hanoverian monarchy had abandoned their allegiance to the Stuarts. In the mid-18th century, the Scottish economy was faltering, and many Highlanders were enduring hardships and impoverishment. Those who supported the Jacobite cause were guaranteed economic benefits such as land reform and an elimination of heavy taxes.

Image from the Jacobite Broadside depicting the “stature, dress, and likeness of the rebel lords” by an unknown engraver (18th Century); unknown/various, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Image from the Jacobite Broadside depicting the “stature, dress, and likeness of the rebel lords” by an unknown engraver (18th Century); unknown/various, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ideological and Religious Factors

The Stuarts were the legitimate rulers of Britain and Scotland, according to the Jacobites, who believed in the divine right of monarchs. They were also motivated by a desire to preserve Scotland’s customary way of life, which they saw as under threat from the Hanoverians and their policies in general.

The majority of Jacobite followers were Roman Catholic, whereas Hanoverians and those who supported them were primarily Protestant.

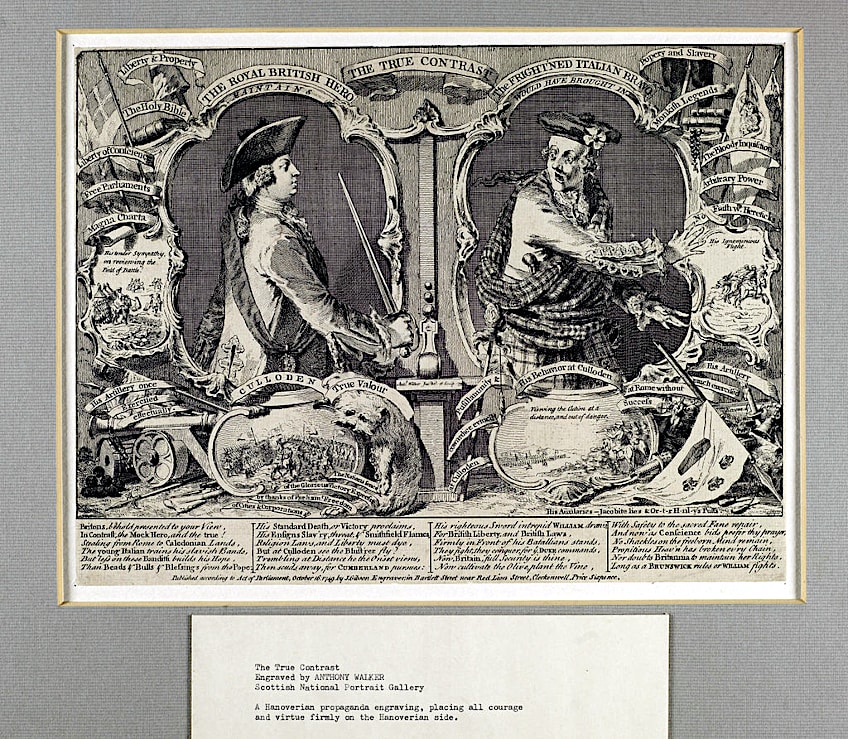

During this time, there was still considerable religious tension in Scotland between Protestants and Catholics, with Catholics facing social and legal discrimination. Some saw the Jacobite struggle as a way to bring back Catholicism to a more prominent place in Scotland. In England, popular publications such as the Jacobite Broadside used various forms of satire and propaganda to vilify the rebels as uncouth barbarians whose cause would lead to the destruction of England.

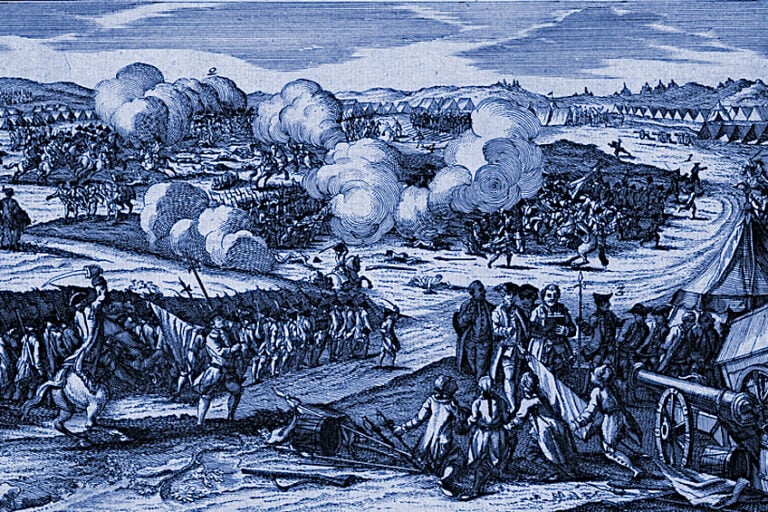

Engraving depicting Jacobean officers attacking one of the King’s men at the battle of Culloden (1747); Creator:British Cartoon Prints Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Engraving depicting Jacobean officers attacking one of the King’s men at the battle of Culloden (1747); Creator:British Cartoon Prints Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ambitions of the Rulers

The man in charge of the Jacobite revolt, Charles Edward Stuart (commonly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie), wanted to reestablish the Stuart line to the crown of Great Britain. His father, James Francis Edward Stuart, had been dethroned in the 1688 Glorious Revolution, and the Hanoverians were now enthroned in his place. Charles considered himself to be the natural heir to the throne, and his plan was to overthrow the Hanoverians and reclaim his rightful place on the British throne

William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and the son of King George II, had been tasked with crushing the Jacobite revolt. His intention was to preserve the status quo and defend the Hanoverian monarchy. He considered the Jacobite rebels and traitors who threatened British stability, and he vowed to destroy their rebellion and reestablish order.

Satirical comparison of William the Duke of Cumberland and Prince Charles Edward Stuart in the Jacobite Broadside (1745 – 1746); National Library of Scotland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Satirical comparison of William the Duke of Cumberland and Prince Charles Edward Stuart in the Jacobite Broadside (1745 – 1746); National Library of Scotland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Culloden Combatants

Were the opposing forces in the battle evenly matched? What were their backgrounds and tactics? Let’s find out more about the Jacobites and the government army they fought against.

The Jacobites

The Jacobite Army is generally considered to have been mostly made up of Catholic Gaelic-speaking Highlanders; nevertheless, approximately one-fourth of the file and rank were enlisted in Forfarshire, Aberdeenshire, and Banffshire, with another 20 percent enlisted in Perthshire. Catholicism was the religion of a minority of people by 1745, and many of those who supported the Rebellion were Episcopalians. While the army was primarily composed of Scots, it also included a few English soldiers as well as a substantial number of Irish and French professionals serving with the Royal Ecossais and Irish Brigade in French service.

The Jacobites relied significantly on the traditional prerogative preserved by many Scottish landlords to enlist tenants for military service in order to quickly mobilize an army. This was based on an expectation of short-term warfare: a lengthy campaign required greater expertise and training, and the colonels of several Highland regiments deemed their troops uncontrollable.

Depiction of a Jacobite Highlander by an unknown engraver (1745 – 1746); National Library of Scotland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Depiction of a Jacobite Highlander by an unknown engraver (1745 – 1746); National Library of Scotland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The highly armed tacksmen led a conventional ‘clan’ unit, with their subtenants acting as regular troops. The tacksmen stood in the front rank, sustaining proportionately heavy fatalities; the Appin Regiment’s gentlemen accounted for one-quarter of those slain and one-third of those injured. Many Jacobite troops, particularly those from the northeast, had been more formally organized and drilled, but, like the Highland battalions, were unprepared and very quickly trained.

The Government Army

Cumberland’s forces at Culloden consisted of 16 infantry battalions, one Irish, and four Scottish. The majority of the infantry regiments had previously experienced battle at Falkirk, but had subsequently been further organized, refreshed, and resupplied. Many of the soldiers were seasoned veterans of Continental service, but when the Jacobite rising broke out, recruits were offered further incentives to bolster the units of depleted troops.

Remains of the King’s color of the King’s Own Regiment of Foot that was carried at Culloden; British Army, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Remains of the King’s color of the King’s Own Regiment of Foot that was carried at Culloden; British Army, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On the 6th of September, 1745, each new recruit who enlisted in the Guards before the 24th received £6, while those who joined in the final days of the month received £4.

In general, a regular single-battalion British infantry regiment was meant to be around 815 men strong, but in actuality, the units were often considerably smaller, and at Culloden, their regiments were not much greater than 400 people. In January 1746, the government troops arrived in Scotland. Many lacked expertise in combat, after spending the previous years fighting smuggling. A regular cavalryman carried a carbine and a pistol, but the British cavalry’s main weapon was a 35-inch sword.

During the Culloden Battle, the Royal Artillery significantly surpassed their Jacobite rivals. However, the government artillery had been performing dismally up to this point in the conflict. The 3-pounder was the artillery’s main weapon. The range of this weapon was 460 meters.

Modern Re-enactment of the Battle of Culloden featuring artillery fire; Edd Scorpio, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Modern Re-enactment of the Battle of Culloden featuring artillery fire; Edd Scorpio, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Arrival of Prince Charles Edward

Between 1708 to 1719, James Francis Edward attempted, with either Spanish or French support, to encourage revolt in Scotland, his forebears’ homeland. Despite its persistent unpopularity, the Hanoverian dynasty still remained strong. So, when word started to spread that the young Prince Charles Edward had arrived in Scotland with a small band of adherents and was amassing supporters among the clans of the highland, there was little concern at first. This all changed in September 1745 when Charles Edward’s men defeated the government’s forces at Prestonpans, captured Edinburgh, and then subsequently entered England that November.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart “The Young Pretender” by Cosmo Alexander (1749); Cosmo Alexander, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Prince Charles Edward Stuart “The Young Pretender” by Cosmo Alexander (1749); Cosmo Alexander, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The highland army at this point numbered around 5,000 men and marched as far as Derby but did not manage to gain any support from the English.

The highland army was then confronted by advancing armies composed of British soldiers who had been called back from combat in the Austrian Succession War in Europe. The army started to retreat back to Scotland on the 5th of December. The highland army was able to defeat the first government army deployed against them at Falkirk after receiving French reinforcements. However, by the time the highland men encountered the Duke of Cumberland’s soldiers on Culloden Moor on the 16th of April, they were demoralized, undersupplied, and the numbers had dwindled due to desertion.

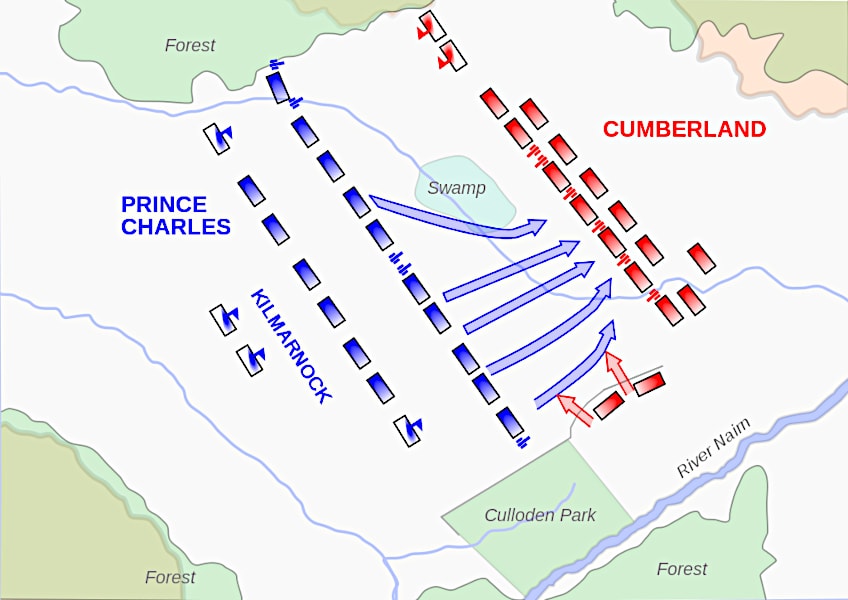

The Battle

The night before the Culloden Battle, the Highland force tried to carry out a surprise attack. However, it had not arrived at Cumberland’s camp by sunrise, having been delayed by men falling behind as they searched for food. They retreated to Culloden Moor, a battleground five miles east of Inverness. The battleground was a poor choice since it provided an unobstructed field of fire for Cumberland’s guns. The highland army was cannonaded for about 30 minutes with no effective form of response.

Battle tactics at the battle of Culloden; Andrei nacu at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle tactics at the battle of Culloden; Andrei nacu at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Orders to attack were conveyed slowly down the highland army’s jumbled line of command, but the highlanders eventually advanced, and they charged over the 320 meters between them and the adversary. Despite being delayed and slowed by the swampy ground, many Highlanders made it to the adversary lines.

The Redcoat approach of bayoneting the more vulnerable side of the individual to the right, instead of attacking the one straight in front, seems to have proven effective in the bloody hand-to-hand fighting that followed. The Highland army ultimately gave up and retreated after less than an hour of fighting. At this moment, regimental cavalry started to push their way around the highlanders’ flanks, turning the defeat into a massacre. They pursued the retreating men all the way to Inverness.

The Aftermath

Under the command of the Master of Lovat, The 2nd battalion regiment, encountered the first of the retreating Highlanders as they neared Inverness. It has been claimed that Lovat deftly switched sides and fought against the fleeing Jacobites, which could account for his meteoric increase in fortune in the following years. Following the Culloden battle, the Lowland regiments of the Jacobites marched southward to Corrybrough before continuing to Ruthven Barracks, while their Highland troops marched northwards toward Inverness and then on to Fort Augustus.

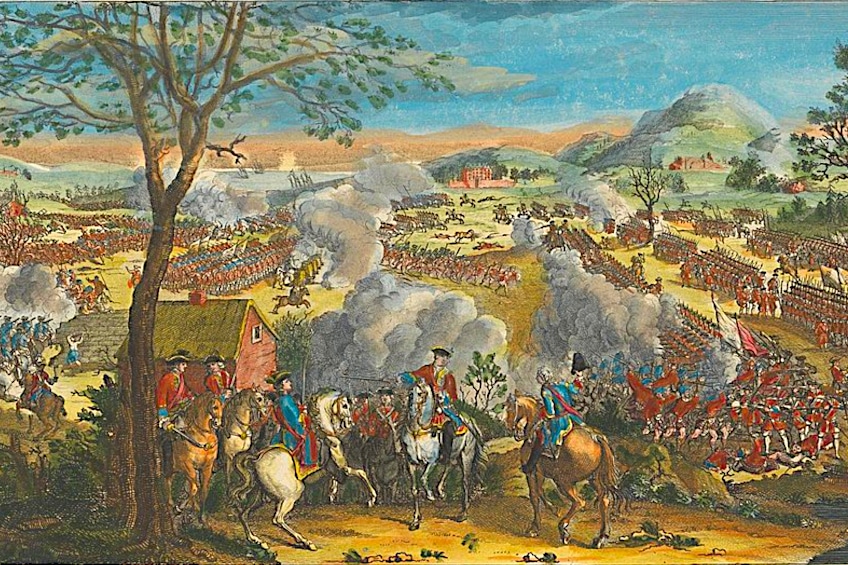

The Battle of Culloden, near Inverness in Scotland by an unknown engraver; Yale Center for British Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Culloden, near Inverness in Scotland by an unknown engraver; Yale Center for British Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

A few of the men present at Ruthven reported that despite being defeated, the Highland men were optimistic and anxious to get back into the battle. In terms of manpower, continuing the Jacobite struggle remained a possibility at that point. At least one-third of the Highlanders had either never made it to or slept through the Battle of Culloden, providing the army a potential force of around 5,000 to 6,000 people. However, the approximately 1,500 troops gathered at Ruthven Barracks obtained orders from Charles to scatter until he arrived with French reinforcement.

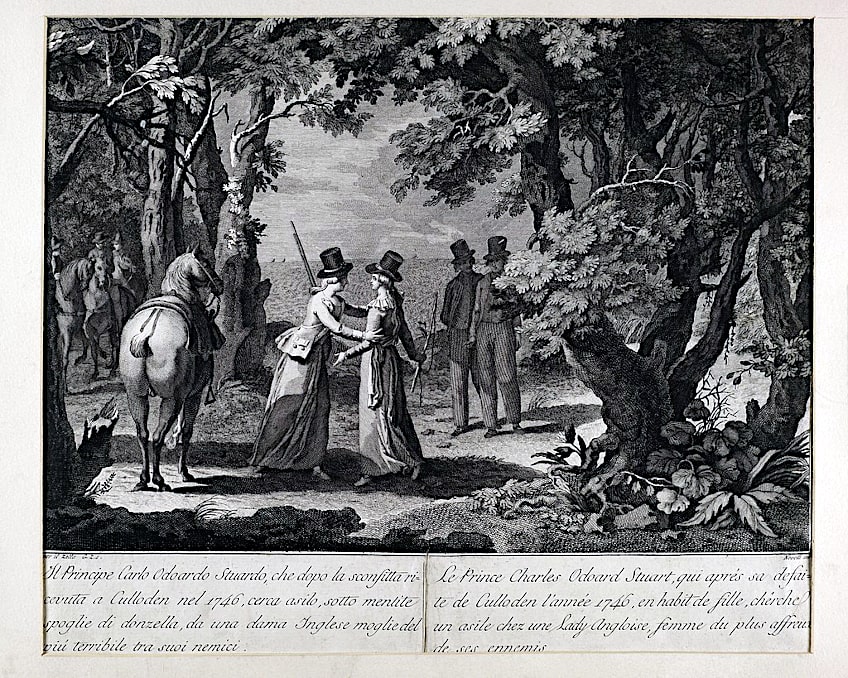

The Highland battalions positioned at Fort Augustus must have been issued similar orders, and by the 18th of April, nearly all of the Jacobite army was completely disbanded. Officers and troops from the French units marched to Inverness on the 19th of April, where they surrendered. The majority of the army disbanded, with men returning home or looking for refuge overseas, while the Appin Regiment, among others, remained ready for action as late as July. Rumor had it that Prince Charles Stuart had escaped from Culloden disguised as a woman.

Jacobite Broadside depiction of Prince Charles Edward Stuart dressed as a lady after his flight from Culloden (1745-460); National Library of Scotland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jacobite Broadside depiction of Prince Charles Edward Stuart dressed as a lady after his flight from Culloden (1745-460); National Library of Scotland, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Following his escape from the battle, Prince Charles Edward Stuart traveled to the Hebrides with a handful of followers.

By the 20th of April, he had arrived in Arisaig on the west coast of Scotland. He departed for the island of Benbecula after having spent a few days with his close companions. He then traveled to Scalpay, and from there to Stornoway. The Prince crisscrossed the Hebrides for almost half a year, chased by supporters of the government and threatened by local noblemen who were ready to take advantage of the £30,000 reward on his head. It was during this time that he met Flora Macdonald, who reportedly helped him flee to Skye. Finally, on the 19th of September, he arrived in Arisaig, where his group boarded two small French vessels that carried them to France, and he never went back to Scotland.

Repercussions

Cumberland cleared the jails that were overcrowded with those that the Jacobites had imprisoned and filled them with Jacobites. Prisoners were transported south to England to face high treason charges. Many were imprisoned in Tilbury Fort, and executions occurred in York, Carlisle, and Kennington Common. The majority of commoner Jacobite sympathizers fared better than those who held rank. In total, 120 commoners were put to death with a third of them being deserters of the British Army. The common inmates selected lots among themselves, and just one out of 20 ended up on trial. Although the majority of those on trial were convicted and sentenced to death, almost every one of them had their sentences reduced to life imprisonment in British colonies.

Satire depicting events related to the Battle of Culloden (c. 1746); British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Satire depicting events related to the Battle of Culloden (c. 1746); British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Following their military victory, the British government enacted legislation to better integrate Scotland, notably the Scottish Highlands, with the remainder of Britain. The Episcopal clergy were forced to swear loyalty to the governing Hanoverian monarchy. The Heritable Jurisdictions Act abolished landowners’ hereditary power to govern justice on their property via barony courts. Before the passing of the Act, feudal lords wielded extensive administrative and military power over their subjects, including the oft-quoted “pit and gallows” powers.

Lords who remained loyal to the government were handsomely reimbursed for the loss of their traditional privileges and powers. Clan chiefs and lords who supported the Jacobite revolt were deprived of their lands, which were subsequently sold and the proceeds used to advance agriculture and trade in Scotland. An Act of Parliament passed anti-clothing legislation against the dress of the highlanders in 1746. As a consequence, tartan was outlawed, save as officers’ and soldiers’ uniforms in the British Army, and later for wealthy men and their offspring.

The Legacy of the Culloden Battlefield

A visitor center is now constructed near the battleground. It first opened in December 2007, with the goal of maintaining the battlefield in the same state it was on the 16th of April, 1746. One distinction is that it is currently overgrown with plants and heather. Yet, during the 18th century, the region served as common grazing land, mostly for employees of the Culloden estate. Visitors may stroll around the site on trails and also enjoy the scenery from above on a high platform. The six-meter-tall monument cairn constructed by Duncan Forbes in 1881 is perhaps the most recognizable relic of the battlefield today. Forbes also placed headstones to memorialize the clans’ mass graves the same year.

The farmhouse of Leanach is from around 1760, however, it is located on the same site as the turf-walled cottage that acted as a field hospital for government forces following the conflict. The burial spot of the government soldiers is said to be marked by “The English Stone” west of the Old Leanach cottage. Another stone, west of this one, was raised by Forbes to indicate the location where Alexander McGillivray of Dunmaglass’s body was discovered after the battle. A stone on the battlefield’s eastern edge is said to mark the location from where Cumberland led the battle.

The battlefield at Culloden; Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The battlefield at Culloden; Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Historic Scotland has inventoried and preserved the battlefield under the Historic Environment Act. Since 2001, the battleground has been subjected to geophysical, topographic, and metal detector studies, as well as archaeological digs. Intriguing discoveries have been uncovered in the locations where most intense combat took place on the government side’s left wing, especially where Dejean’s and Barrell’s troops were stationed. Broken musket pieces and pistol balls, for instance, have been discovered here, indicating close-quarters combat, as pistols were only employed at close range, and the musket pieces seem to have been destroyed by pistol balls or heavy broadswords.

Weapons Found at the Site

Musket ball findings appear to indicate where the lines of soldiers stood and fought. Some of the musket balls seem to have been dropped without being shot, while others look like they missed their intended targets and have been deformed from impact with human bodies. In some situations, it’s possible to determine whether the shots were fired by government soldiers or Jacobites because Jacobite forces are known to have utilized a considerable number of French muskets, which discharged a slightly smaller caliber shot than the British Army’s weapons.

The findings confirm that the Jacobites utilized muskets in greater quantities than previously assumed. Mortar shell remnants were discovered a short distance from where the hand-to-hand combat took place.

Collection of swords used at the battle of Culloden on display in Edinburgh Castle; Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Collection of swords used at the battle of Culloden on display in Edinburgh Castle; Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Though Forbes’ stones indicate the graves of Jacobites, the whereabouts of the remains of over 60 government troops remain unknown. The recent finding of a silver Thaler from 1752, though, may lead archaeologists to the graves. A geophysical examination right beneath the coin’s discovery site appears to reveal the presence of a massive rectangular burial trench. The coin could have been dropped by a member of the military who formerly served in the wars on the Continent while visiting the graves of his dead companions. The National Trust for Scotland is actively attempting to restore Culloden Moor as closely as possible to its pre-Battle of Culloden Moor form.

The Battle of Culloden marked the end of the Stuart dynasty’s ambitions to recapture the throne in Britain and the decisive defeat of the Jacobite revolt of 1745. For many years, the Jacobite struggle had been a source of stress in Scotland, and the defeat suffered at Culloden largely ended the prospect of another insurrection. The impact of the Culloden Battle on Scottish society was also substantial. Following the conflict, the British government imposed a number of severe measures aimed at crushing the Highlands clans and deterring future uprisings.

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the Battle of Culloden?

The Culloden Battle took place on the 16th of April, 1746. The actual battle did not last very long though, and it is estimated that the whole thing was over in an hour. There were further conflicts that followed after the battle when the two sides encountered each other as the Highlanders fled.

Who Won the Battle of Culloden?

The battle was won by the British government soldiers, with the highland troops suffering major losses due to being tired and hungry upon arriving at the battle. Only around 50 of the government troops were said to have died. On the other hand, there were around 1500 slain soldiers from the highland army. Prince Stuart fled to France after losing the battle.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.