Battle of Saratoga – Proving American Revolutionary Resilience

What was the Battle of Saratoga all about and why did the Battle of Saratoga happen in the first place? The Battle of Saratoga is regarded as a defining moment in the American Revolutionary War. The outcome demonstrated that the Americans could hold their own against Britain, paving the way for an alliance with France. In this article, we will provide a description and summary of the Battle of Saratoga, with the aim of finding out what happened and answering related questions, such as “why was the Battle of Saratoga a turning point in the War against the British?”.

Contents

The Battles of Saratoga Summary

| Name of Battle | Battle of Saratoga |

| War Associated With | American Revolutionary War |

| First Battle | 19 September 1777 |

| Second Battle | 7 October 1777 |

| Location of Battle | Stillwater, Saratoga County, New York, United States |

What is now known as the Battle of Saratoga refers to two separate engagements that took place during the fall of 1777. The first battle of Saratoga occurred at Freeman’s Farm on the 19th of September, the second Battle of Saratoga took place at Bemis Heights on 7 October.

The impact of these two battles were of such significance to the revolutionary cause that they are commonly regarded as a single military event.

The British adapted their strategy as the American Revolutionary War approached its two-year mark. They intended to divide the Thirteen Colonies and separate New England from the far more Loyalist southern and middle colonies. In 1777, the British leadership prepared a three-way pincer strategy to separate the colonies. The west pincer, led by Barry St. Leger, was to travel from Ontario to western New York via the Mohawk River, while the south pincer was to travel from New York City along the Hudson River valley. The north pincer was supposed to move south from Montreal, and the three troops were supposed to meet around Albany in New York, separating New England from the rest of the colonies.

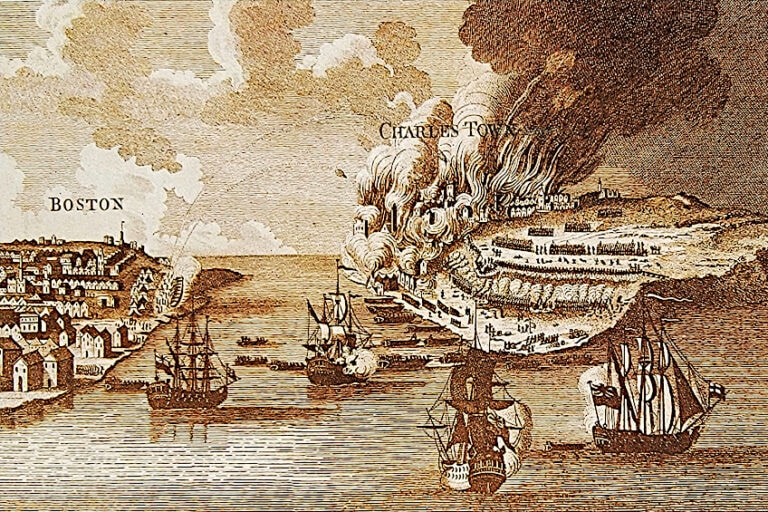

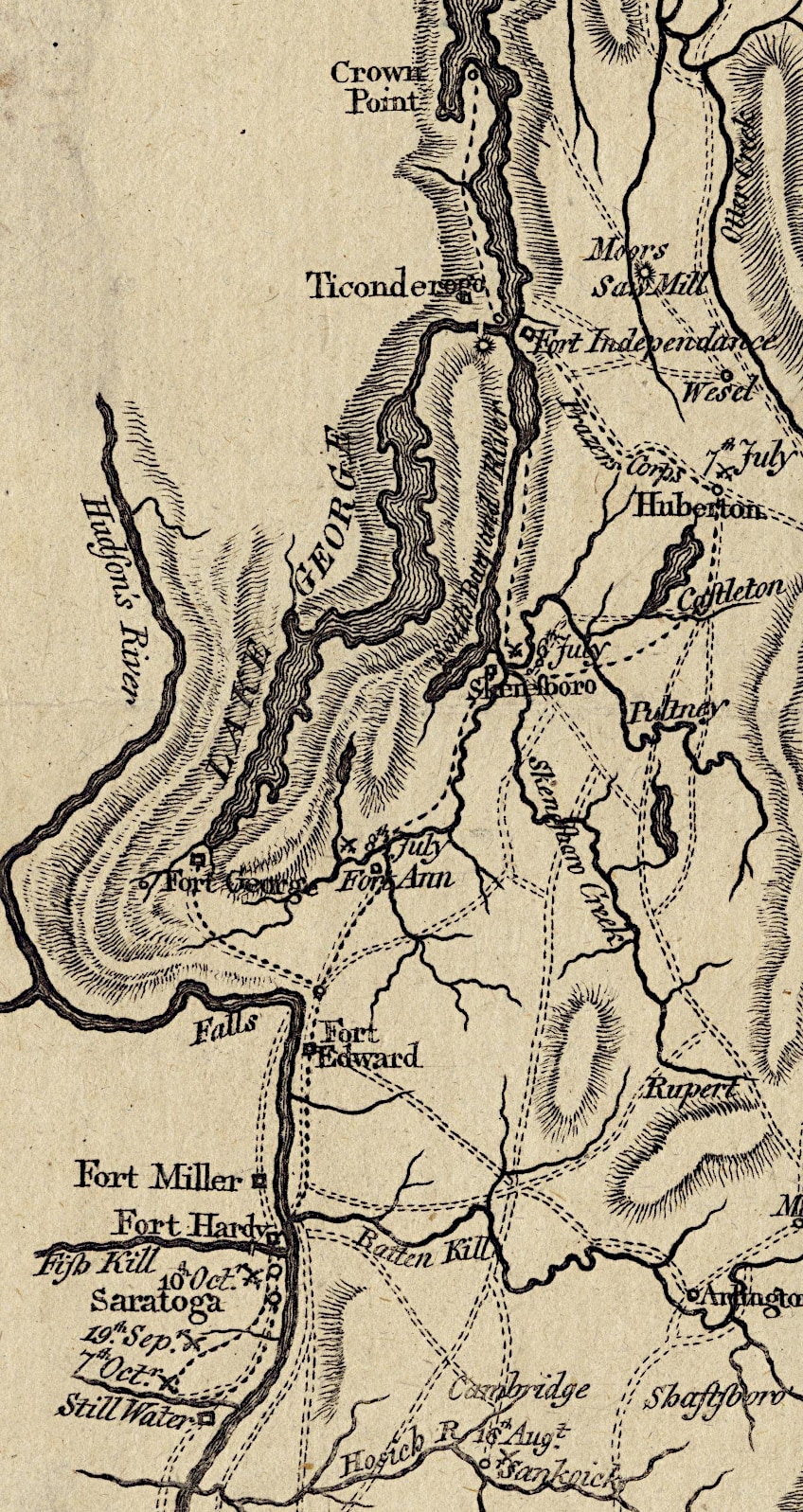

Map showing the geographic area of General John Burgoyne’s 1777 Saratoga Campaign (1780); William Faden, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Map showing the geographic area of General John Burgoyne’s 1777 Saratoga Campaign (1780); William Faden, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Pre-Battle British Situation

In June 1777, British General John Burgoyne advanced south from the province of Quebec to take possession of the upper Hudson River valley. After his victory at Fort Ticonderoga, his expedition had become mired with one problem after another. Parts of the army had arrived on the upper Hudson by the end of July, but logistic supply issues postponed the main army’s arrival at Fort Edward. At the Battle of Bennington on the 16th of August, almost 1,000 troops died or were taken prisoner in an attempt to address these issues.

On the 28th of August, Burgoyne learned that St. Leger’s army that was heading down the Mohawk River valley had decided to turn back following the disastrous Siege of Fort Stanwix.

General John Burgoyne by Joshua Reynolds (c. 1766); Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

General John Burgoyne by Joshua Reynolds (c. 1766); Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Instead of advancing north to meet Burgoyne, Howe had sent his army by sea from New York City on an expedition to seize Philadelphia. Following the defeat at Bennington, the majority of Burgoyne’s Native American supporters had left, rendering his situation challenging.

He needed to reach safe winter quarters, which meant either retreating back to Ticonderoga or advancing to Albany, and he chose the latter.

He then purposefully blocked connections to the north in order to avoid having to maintain a network of strongly defended outposts between his position and Ticonderoga, and he chose to traverse the Hudson River while he still held a fairly strong position. He directed the army’s rear to leave outposts from Skenesboro, and subsequently directed the army to traverse the Hudson directly north of Saratoga between the 13th and 15th of September.

The Pre-Battle American Situation

Since Burgoyne’s conquest of Ticonderoga in early July, the Continental Army had been in a sluggish retreat south to Stillwater in New York. Major General Horatio Gates then took charge on the 19th of August. General George Washington’s strategic moves benefited Gates’ army as well.

Washington was especially anxious about General Howe’s movements. He was well aware that Burgoyne was also on the move, so he decided to take a few risks that July.

Major General Benedict Arnold and Major General Benjamin Lincoln were ordered north to help. In August, before he knew for sure that Howe had gone south, he dispatched 750 soldiers from Israel Putnam’s troops guarding the New York highlands to accompany Gates’ army.

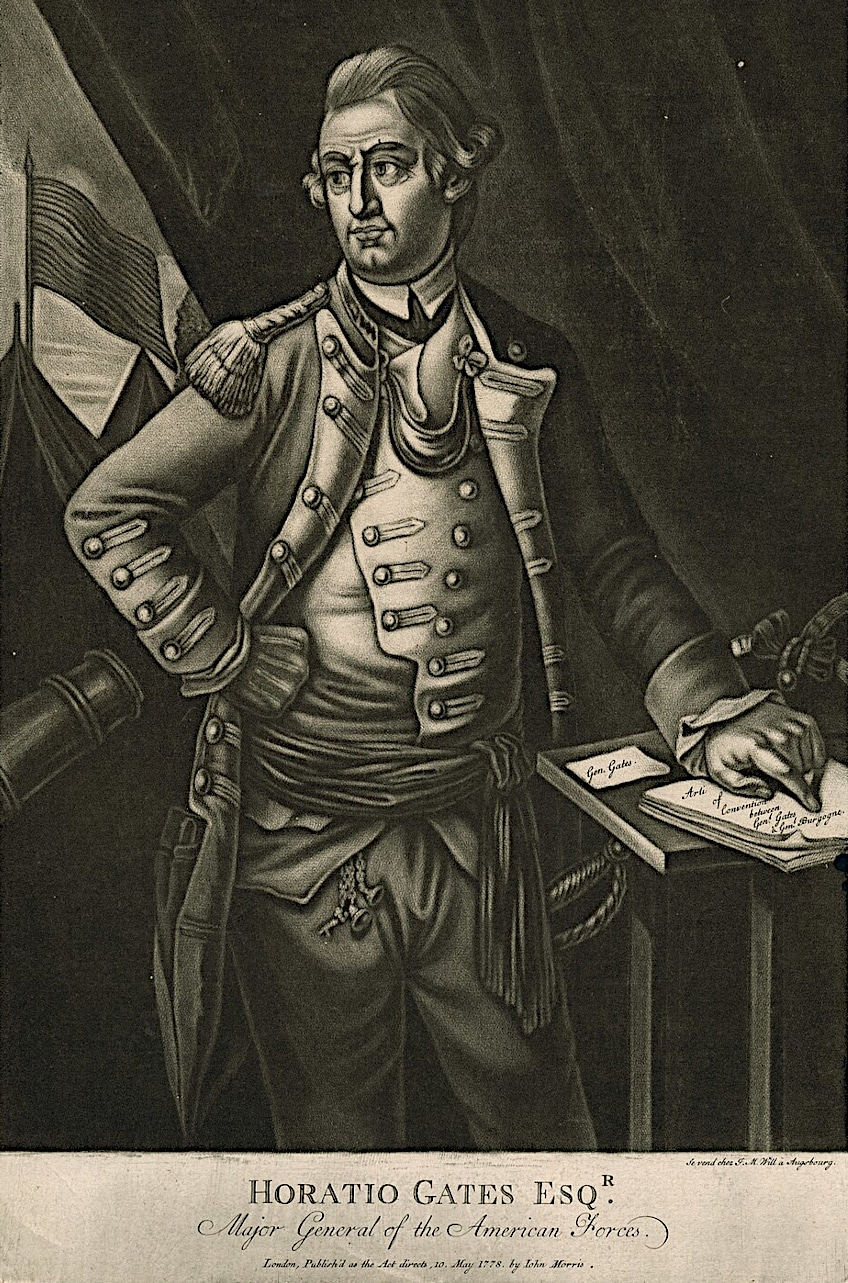

Horatio Gates by an unknown artist (published 1778); Scan by NYPL, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Horatio Gates by an unknown artist (published 1778); Scan by NYPL, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Colonel Morgan and the newly established Provisional Rifle Corps, which consisted of around 500 carefully picked riflemen from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia selected for their sharpshooting abilities, were also deployed. The name given to this regiment was Morgan’s Riflemen.

Gates instructed his force to head north on the 7th of September. Bemis Heights, roughly 16 kilometers south of Saratoga, was chosen for its defensive qualities; the army spent about a week erecting defensive fortifications directed by Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

The heights offered an unobstructed view of the surrounding region and dominated the sole road to Albany, which crossed through an opening between the Hudson River and the heights. The heavily wooded cliffs to the west of this area would provide a substantial barrier to any well-equipped force.

September 19th: The First Saratoga Battle

Burgoyne pushed to the south after crossing the Hudson with caution. On the 18th of September, his army’s vanguard arrived just north of Saratoga, some six kilometers from the defensive line of the Americans, when clashes broke out among American scouting groups and the leading troops of his army. Since Arnold’s return from Fort Stanwix, the American encampment had been a hotbed of intrigue.

Despite the fact that he and Gates had previously been on pretty good terms, Arnold succeeded in turning Gates against him. The circumstances had not yet reached a boiling point on the 19th of September, but the events of the day had added to the tension.

Prelude to the Battle

Gates had given Arnold leadership of the left wing of the fortifications and seized control of the right. Arnold and Burgoyne both recognized the significance of the American left and the necessity to seize the heights there.

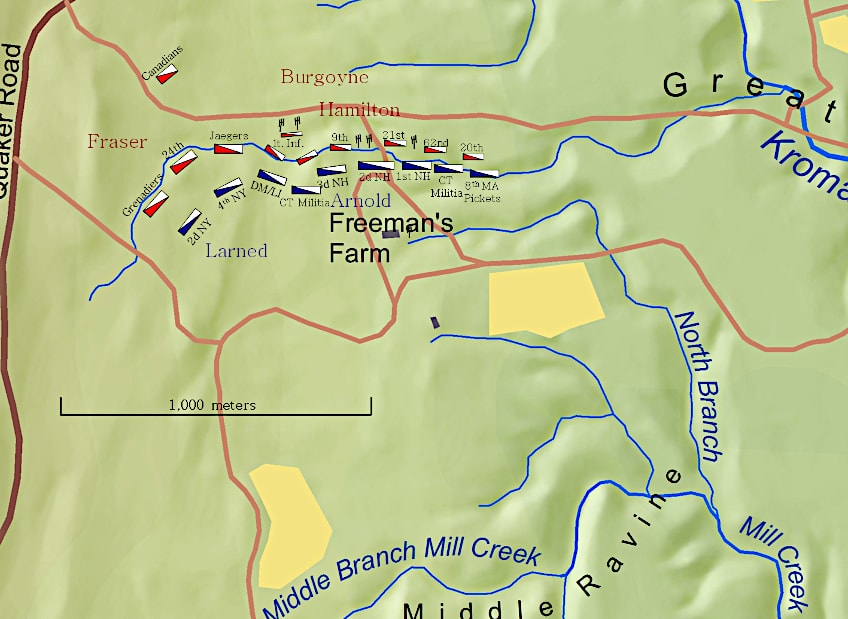

Burgoyne directed the soldiers to advance in three columns as the morning fog dissipated around 10 a.m. that morning.

General Fraser led the right wing over the thickly forested high ground north and west of Bemis Heights, with the intention of turning the American left flank. Arnold recognized the possibility of a flanking maneuver and requested Gates for permission to move his troops from the heights to meet this anticipated maneuver head-on, where the American aptitude in forest battle would be advantageous.

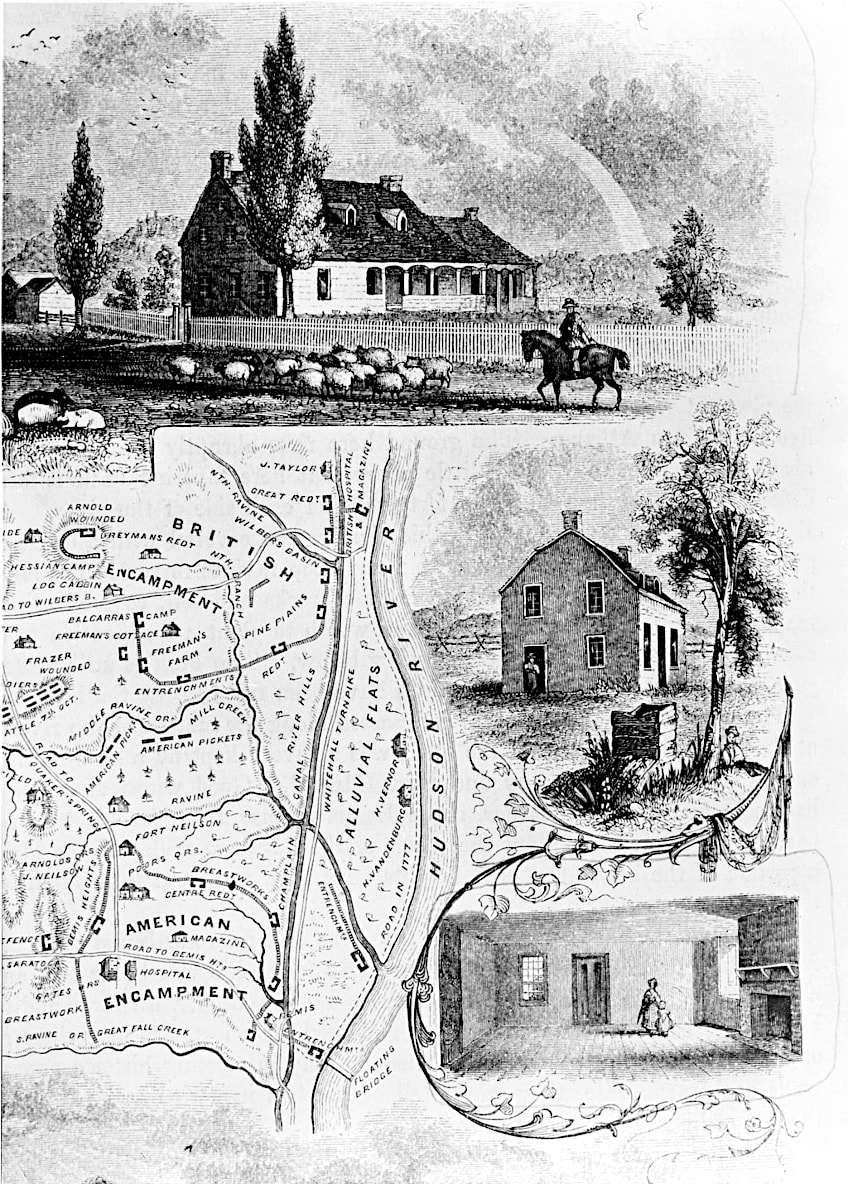

Plan of the battlefield of Saratoga with views of John Neilson’s house where Generals Benedict Arnold and Enoch Poor were headquartered from Benson Lossing’s Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution (1851); Benson John Lossing, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Plan of the battlefield of Saratoga with views of John Neilson’s house where Generals Benedict Arnold and Enoch Poor were headquartered from Benson Lossing’s Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution (1851); Benson John Lossing, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gates, whose favored tactic was to stay back and wait for the anticipated frontal attack, reluctantly allowed a scouting group of Daniel Morgan’s soldiers.

Morgan’s soldiers then encountered British advance forces in a clearing on Freeman’s Farm northwest of Bemis Heights. The two other columns were still making their way to this open field. Riedesel’s army was impeded on the way by obstructions laid down by the American troops. The sound of firing to the west pushed Riedesel to send some of his armed troops that way. Morgan’s soldiers then encountered an advancing unit from Hamilton’s column.

American Riflemen from Col. Daniel Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps at the Battle of Saratoga by Hugh Charles McBarron, Jr. (1975); Published by U.S. Government Printing Office; painting by Hugh Charles McBarron, Jr. (1902-1992), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

American Riflemen from Col. Daniel Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps at the Battle of Saratoga by Hugh Charles McBarron, Jr. (1975); Published by U.S. Government Printing Office; painting by Hugh Charles McBarron, Jr. (1902-1992), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The First Battle of Saratoga

Morgan strategically deployed marksmen, who subsequently killed nearly every soldier in the advancing company. Morgan and his troops then attacked, not realizing they were heading straight toward Burgoyne’s main group. While the advancing company was driven back, Fraser’s frontal assault emerged just in time to strike Morgan’s left, his troops pushed back into the dense forest.

After riding ahead to view the fire, James Wilkinson withdrew to the American encampment for reinforcements. As the British regiment retreated into the main column, the column’s front line opened fire, killing several of their own soldiers.

The combat then progressed through periods that alternated between heavy fighting and pauses in the action. Morgan’s troops had reassembled in the forest and had taken commanders and artillerymen hostage. They were so efficient at decreasing the latter that the Americans obtained momentary control of British field artillery only to lose them during the next British attack on numerous occasions. At a certain point, it was thought that Burgoyne had been killed by a sniper; however, the person who died was one of Burgoyne’s assistants riding a finely dressed horse.

Field array at at the outset of the Battle of Freeman’s Farm on 19 September 1777; Charles E. Frye, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Field array at at the outset of the Battle of Freeman’s Farm on 19 September 1777; Charles E. Frye, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Riedesel dispatched a messenger to Burgoyne for orders at about 3 p.m. He reappeared two hours later, not only with orders to watch the luggage train but also with instructions to dispatch as many soldiers as he was able to spare to the American’s right flank. Riedesel took a calculated risk by leaving 500 soldiers to protect the important supply train as the remainder of his column advanced toward the battle. Luckily for the American right, night descended, bringing the battle to a close for the day. The Americans returned to their defensive positions, abandoning the British on the field.

Burgoyne had won the battle, but his forces sustained about 600 fatalities with three-quarters of the artillerymen dead or injured. Nearly 300 Americans were killed or critically injured in the battle that day.

Interlude

Burgoyne’s council debated whether to launch another attack the very next day, and a decision was made to postpone further action until more reinforcements had arrived. During this time, there were practically daily conflicts between the two armies’ patrols.

Morgan’s sharpshooters, who had extensive training in forest warfare tactics and strategy, regularly attacked British troops on the western flank.

As September progressed into October, it became evident that no one would be arriving to support Burgoyne, who had already placed the troops on rations on the 3rd of October. The following day, Burgoyne convened a military council, during which Riedesel recommended withdrawal. Burgoyne turned down the idea, insisting that withdrawal would be humiliating.

View of the west bank of the Hudson’s River 3 miles above Still Water, upon which the army under the command of General Burgoyne took post on the 20th Sepr. 1777 by an unknown artist (published between 1777 and 1890); Scan by NYPL, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

View of the west bank of the Hudson’s River 3 miles above Still Water, upon which the army under the command of General Burgoyne took post on the 20th Sepr. 1777 by an unknown artist (published between 1777 and 1890); Scan by NYPL, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

October 7th: Second Battle of Saratoga

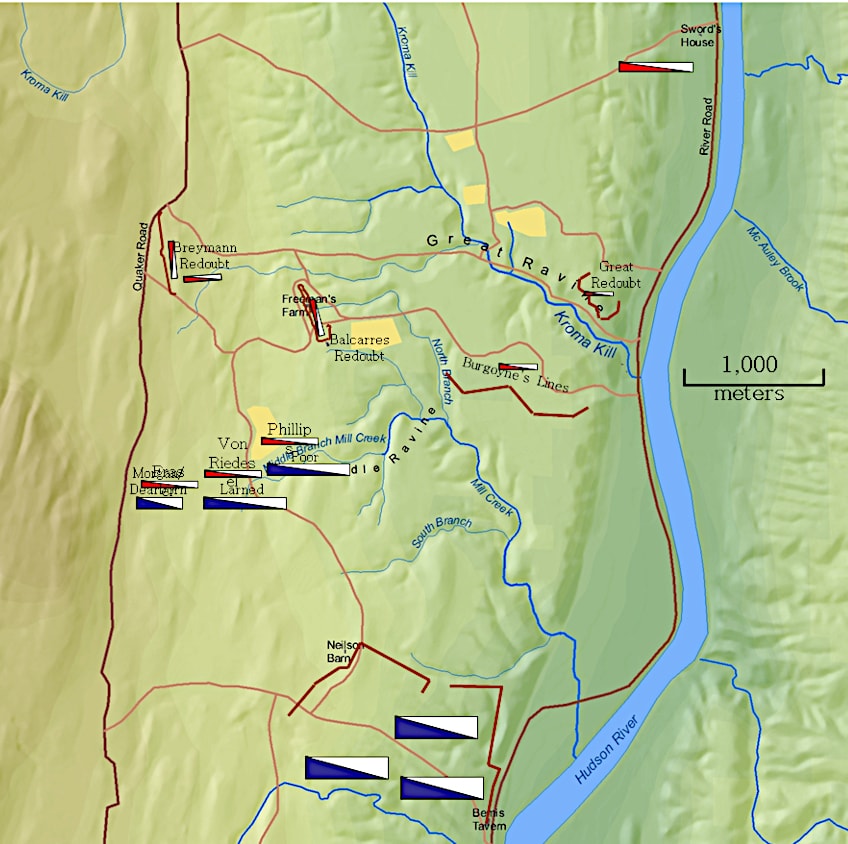

On the 7th of October, they eventually agreed to launch an offensive on the American’s left flank with 2,000 troops, or over a third of the British army. However, the army he was planning to attack had grown significantly in the interim period. In addition to the detachment’s return sent by Lincoln, troops and provisions kept on arriving at the American camp, including important increases in ammunition stock, which had been critically exhausted during the first battle.

On the 7th of October, Burgoyne encountered an army of about 12,000 troops headed by a man who understood the magnitude of the problems Burgoyne was dealing with. Gates had obtained constant intelligence from the influx of deserters fleeing the British lines, as well as intercepted Clinton’s negative reply to Burgoyne’s call for assistance.

Field array at at the outset of the Battle of Bemis Heights on 7 October 1777; Charles E. Frye, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Field array at at the outset of the Battle of Bemis Heights on 7 October 1777; Charles E. Frye, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The British Maneuvers

While Burgoyne’s army was actually bigger, he likely only had approximately 5,000 combat-ready men on the 7th of October, since casualties from earlier fights and deserters after the September battle had weakened his forces. General Riedesel once again recommended that the troops withdraw. Burgoyne chose to reconnoiter the American’s left flank to determine the potential success of an offensive. The generals selected Fraser’s Advanced Corps as guides, with light soldiers on the right, British grenadiers on the left, and an army drawn from all of the army’s German divisions in the middle. They proceeded about one kilometer to a hill above Mill Brook, where they paused to examine the American position.

While there was some space for artillery to operate on the field, the flanks were perilously close to the surrounding forests. General Lincoln took command of the American left while Gates commanded the American right flank.

When American scouts informed Gates of Burgoyne’s movement, he directed Morgan’s riflemen to the far left, followed by Poor’s men on the left, New York Regiments on the right, and the others in the middle. Behind Learned’s line was a force of 1,200 New York militiamen led by Brigadier General Broeck. Over 8,000 American soldiers joined the battle that day, including approximately 1,400 troops from Lincoln’s command who were dispatched as the fighting grew more intense. Around 2:30 p.m., the British grenadiers opened fire. Poor’s soldiers held their fire, and the landscape rendered British fire ineffectual.

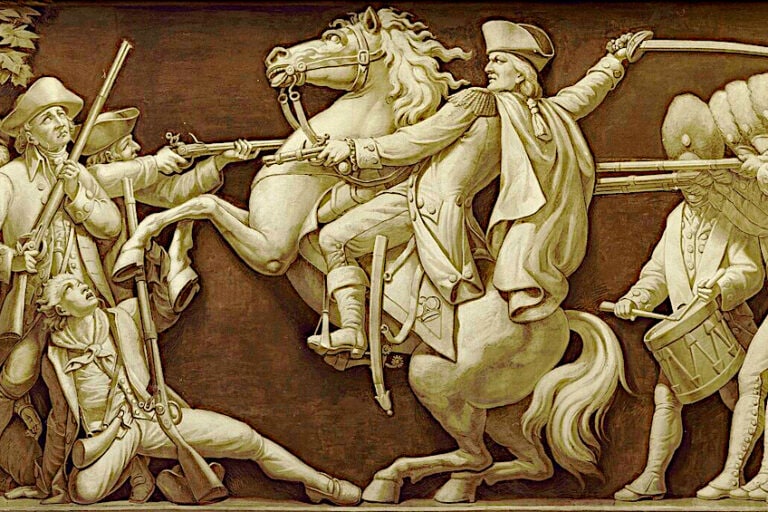

Battle of Saratoga by Johann Martin Will (published 19 September 1777); Johann Martin Will, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle of Saratoga by Johann Martin Will (published 19 September 1777); Johann Martin Will, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Americans eventually started shooting at close range after Major Acland led the English grenadiers in a bayonet attack. Acland was wounded in both legs and several of the grenadiers were killed. Their column was destroyed, and Poor’s troops approached to capture Williams and Acland along with their weaponry. Events were also not turning out well for the English on the American left. Morgan’s soldiers quickly eliminated the Native Americans and Canadians in order to fight Fraser’s regulars. Despite being outnumbered, Morgan was able to thwart multiple British efforts to march west.

While General Fraser was fatally wounded during this period of the battle, Luzader believes a widely circulated tale saying it resulted from a shot delivered by one of Morgan’s troops, Timothy Morgan, was actually made up in the 19th century.

The defeat of Fraser, along with the arrival of Broeck’s potent militia brigade (about equivalent in size to the whole British scouting group), shattered the British will, and they launched a disorderly retreat into their entrenchments. Burgoyne was also almost murdered by one of Morgan’s marksmen, who struck his horse, waistcoat, and hat. In the first part of the battle, Burgoyne lost about 400 soldiers, including the capture of the majority of the grenadier leadership and six of the 10 artillery pieces sent into battle.

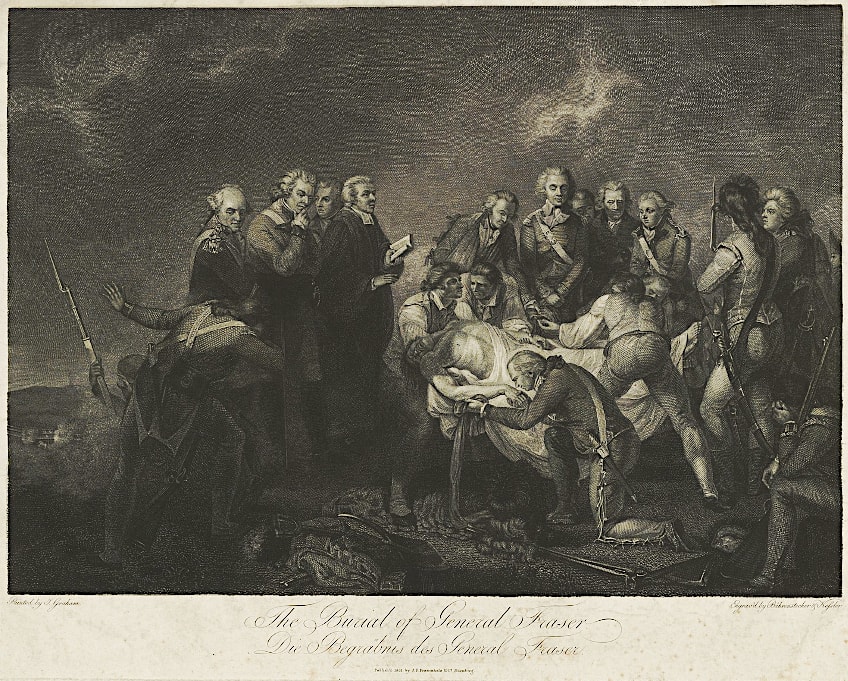

The Burial of General Fraser by and unknown artist; Popular Graphic Arts, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Burial of General Fraser by and unknown artist; Popular Graphic Arts, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The American Attack

The American side was joined at this moment by an unexpected guest. General Arnold, who had been dismissed from his position earlier, and may have been inebriated at the time, galloped out to join the battle. Major Armstrong was instantly dispatched after him with instructions to return; Armstrong, however, did not manage to catch up with him until the fighting was almost finished.

(According to a letter submitted by a witness to the camp procedures, General Arnold did, in fact, get Gates’ permission to take part in this battle).

Benedict Arnold by Thomas Hart (1776); Thomas Hart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Benedict Arnold by Thomas Hart (1776); Thomas Hart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Two redoubts anchored the fortifications on the right flank of the British camp. The outermost one was guarded by around 300 troops led by Heinrich von Breymann, and the other was led by Lord Balcarres. Between these two fortifications, a small group of Canadians controlled the terrain. Because Breymann’s position was somewhat to the north and farther away from the initial battle, the majority of the retreating army went for Balcarres’. Arnold commanded the American assault before leading Poor’s troops in an assault on the Balcarres redoubt.

Balcarres had well-prepared his fortifications, and the redoubt was defended in such a fierce battle that Burgoyne later wrote, “A greater degree of endurance than they exhibited is not in any officer’s memory”.

Arnold proceeded toward the battle, hazardously riding across the lines and miraculously escaping unharmed, seeing that the advance had been blocked and that Learned was ready to strike the Breymann redoubt. He led Learned’s troops through the breach between the redoubts, exposing the back of Breymann’s location, while Morgan’s soldiers were circling around from the far side. The redoubt was captured in a fierce struggle, and Breymann died in the conflict. Arnold’s horse got hit in one of the last volleys, and the falling horse shattered Arnold’s leg. Arnold was subsequently confronted by Major Armstrong, who formally ordered him to return to headquarters. General Arnold had hoped he’d been shot in the heart, knowing that if he died in combat, he’d be remembered as a martyr and revered by the public.

Benedict Arnold at the Second Battle of Saratoga by an unknown artist (19th Century); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Benedict Arnold at the Second Battle of Saratoga by an unknown artist (19th Century); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The seizure of Breymann’s redoubt revealed the British camp, but it was almost dark. An effort by a few Germans to recover the redoubt failed as night fell and an untrustworthy escort led them near the American line.

The Surrender

Burgoyne suffered the loss of 1,000 troops between the two events, rendering him outnumbered by around three to one. Approximately 500 Americans were killed or injured. Burgoyne had additionally lost some of his most qualified commanders, his attempts at capturing the American position were unsuccessful, and his forward line had been broken.

Following the last battle, Burgoyne lit massive fires at the front posts and retreated under cover of night. His troops retreated around 16 kilometers north, to Schuylerville in New York. He had returned to the entrenched positions he had originally held on the 16th of September by the morning of the 8th of October. With his army besieged, Burgoyne convened a council of war on the 13th of October to discuss the conditions of surrender.

Riedesel proposed that they be given parole and permitted to travel back to Canada without any weaponry. Burgoyne believed the Americans would disapprove of such terms and instead requested transportation to Boston, from where they would travel back to Europe by boat. The two parties signed the terms of surrender after many days of negotiations. Burgoyne surrendered his forces to the Americans on the 17th of October. As the British and German forces walked out in surrender, they received the usual honors of battle.

Surrender of General Burgoyne by John Trumbull (1821); John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Surrender of General Burgoyne by John Trumbull (1821); John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

These soldiers came to be known as the Convention Army, so named due to the convention that authorized their safe return to Europe. However, when the Continental Congress subsequently annulled this convention the troops were imprisoned until the end of the war.

The Aftermath of the Battle of Saratoga

Burgoyne’s unsuccessful campaign represented a historic turning point in the Revolutionary War. Burgoyne departed for England and never received another command post in the British Army again. The British found out the hard way that the Americans could fight courageously and successfully. The Revolutionaries’ victory also caught the attention of the French king Louis XVI, paving the way for the alliance with France that would greatly contribute to American success against Britain.

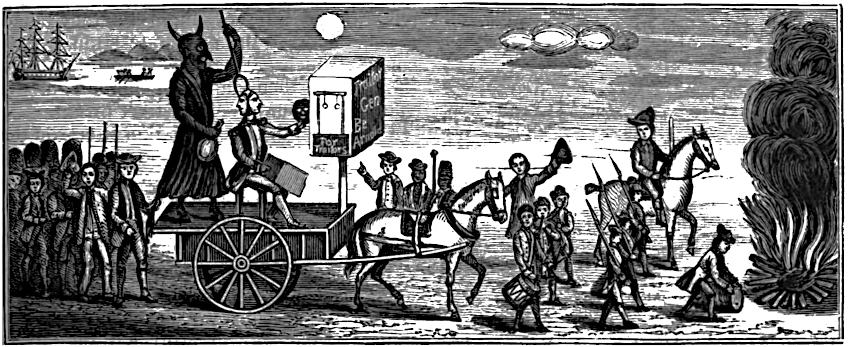

French Satire depicting the defeat of General Burgoyne at Saratoga by an unknown artist (1781); British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

French Satire depicting the defeat of General Burgoyne at Saratoga by an unknown artist (1781); British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

While General Arnold’s seniority was restored in acknowledgment of his service in the battles, the wound he received in the Battle of Saratoga left him bedridden for five months.

Arnold subsequently engaged in treasonous interactions with the British while still incapacitated but acting as Philadelphia’s military governor.

He was commanding the fort at West Point and was involved in a plot to surrender it to the British. He then fled into British lines when his accomplice John Andre was apprehended, exposing the conspiracy. Arnold went on to participate in a 1781 British campaign in Virginia under the commander of Burgoyne’s right-wing, William Phillips. The name Benedict Arnold soon became synonymous with treason.

Depiction of the burning of an effigy of Benedict Arnold by and unknown artist (1876); Century illustrated Volume 12, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Depiction of the burning of an effigy of Benedict Arnold by and unknown artist (1876); Century illustrated Volume 12, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although he delegated leadership to subordinates during battle, General Gates was considered by many as the commanding general of the biggest American victory of the Revolutionary War up to that point. He and others may have plotted to depose George Washington as commander-in-chief. Rather, he was given leadership of the substantial American army in the southern region. He, unfortunately, led it to a horrible loss at the Battle of Camden in 1780, where he executed a hurried retreat. Gates never again led soldiers in the field again.

After Burgoyne’s surrender, Congress announced that the 18th of December was to be recognized as a national day “for heartfelt Thanksgiving and praise”; it was the country’s first formal celebration of a holiday of that name.

The Legacy of the Battle of Saratoga

Burgoyne’s surrender site and the battlefield have been conserved as the Saratoga National Historical Park. The park preserves several historical buildings in the neighborhood and features a number of notable monuments. Most of the niches on the Saratoga Monument obelisk house sculptures of American commanders. Sculptures of Schuyler, Gates, and Colonel Daniel Morgan are the commanders represented. The fourth niche, which would have housed Arnold’s sculpture, remains empty.

The Boot Monument is a spectacular homage to Arnold’s heroics that is unique amongst American memorials in that it does not name its honoree.

Boot Monument to Benedict Arnold in Saratoga National Historical Park; Manuela Michailescu, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Boot Monument to Benedict Arnold in Saratoga National Historical Park; Manuela Michailescu, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It was presented by John Watts de Peyster, a Civil War General, and depicts a major general’s boot with spurs and decorations. It pays tribute to “the most outstanding soldier of the Continental Army”, and stands where Arnold was wounded on the 7th of October while attacking Breymann’s redoubt.

Before we go, let’s look at the Battle of Saratoga in summary. The Battle of Saratoga was a historically important event in the American Revolutionary War. But why was the Battle of Saratoga a turning point in the war against the British? The American defeat over the greater British force boosted the patriot’s morale, increased the prospect of independence, and helped obtain the necessary foreign backing to win the war. Saratoga was one of the most critical engagements of the American Revolutionary War, ending British general Burgoyne’s efforts to seize the Hudson River Valley. The outcome persuaded King Louis XVI’s Court that the American troops were capable of holding their own against the British, thereby securing the partnership between the Americans and the French. Benedict Arnold, an American commander, was lauded as a hero for his gallantry on the battlefield, but his image suffered as a result of his subsequent treason and defection to the British Royalists.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Battle of Saratoga Remembered For?

As with any war, there are certain defining moments that can change the trajectory of events, and the Battle of Saratoga is one such example. It proved once and for all that the Americans were more than capable and willing to defend what was theirs from the British. It also went a long way to persuade the French that they could work together with the Americans to overthrow the British rule once and for all.

Why Did the Battle of Saratoga Happen?

Saratoga, located on the Hudson River in New York, was regarded as a significant location. Securing the Hudson River Valley was critical for both the Americans and the British because it supplied a major river route for troops and supply transportation. In order to capture the American colonies, the British designed a three-pronged approach. General Burgoyne had been charged with sending an army south from Canada, with the goal of cutting New England off from the rest of the surrounding colonies and isolating the uprising. The intention was to join other British soldiers in Albany, thereby dividing the American forces. The American soldiers attempted to maintain their positions while preventing the British from entering Albany, headed by General Gates and enabled by General Arnold.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.