Minoan Art – Exploring the Ancient World of Minoan Artifacts

The Minoan society was one of the first advanced civilizations on the Aegean island of Crete, which thrived during the Bronze age. This civilization is not often heard of today, yet, its cultural and artistic influence has affected many other Mediterranean and Near East settlements, including the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Cyprus, Anatolia, Levantine, the Cyclades, and Canaan. This article will introduce you to Minoan art and culture as envisioned through painting, sculpture, and artifacts.

Contents

The Minoan Civilization

The Minoan civilization once thrived between 3500 BCE and 1100 BCE on the Aegean island of Crete and was recognized as the first advanced civilization in Europe. This complex society developed the foundations of what modern-day scholars would recognize as sophisticated art, including architectural designs and writing systems. The rediscovery of the Minoan civilization occurred in the 20th century with the term “Minoan” originating from a mythical figure named King Minos.

The term “Minoan” was then coined by the archaeologist who rediscovered the civilization at Knossos, Sir Arthur Evans.

Palace of Zakros ruins, Eastern Crete; Vladimír Držík, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Palace of Zakros ruins, Eastern Crete; Vladimír Držík, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

What makes studying the art and culture of this civilization is that the Minoans were the first known “link in the European chain” and thus, the art that emerged from this civilization set the script for thinking around traditional European art and what aspects of Minoan art remain today. The Minoan civilization was famous for its monumental and ornate palaces that reached heights of up to four stories high and were decorated with frescoes.

Another important aspect of Minoan culture was trading since the Aegean and Mediterranean regions witnessed a period of increased trade, especially toward the Near East.

This is how the culture and artistic influences spread to other regions such as the Old Kingdom of Egypt and Anatolia with the best-preserved artworks remaining in Akrotiri, Santorini. Around 1600 BCE, a massive eruption destroyed Akrotiri and left significant damage to Crete and the surrounding islands. Dubbed the Minoan eruption, the Akrotiri disaster was one of the biggest volcanic eruptions in Earth’s history.

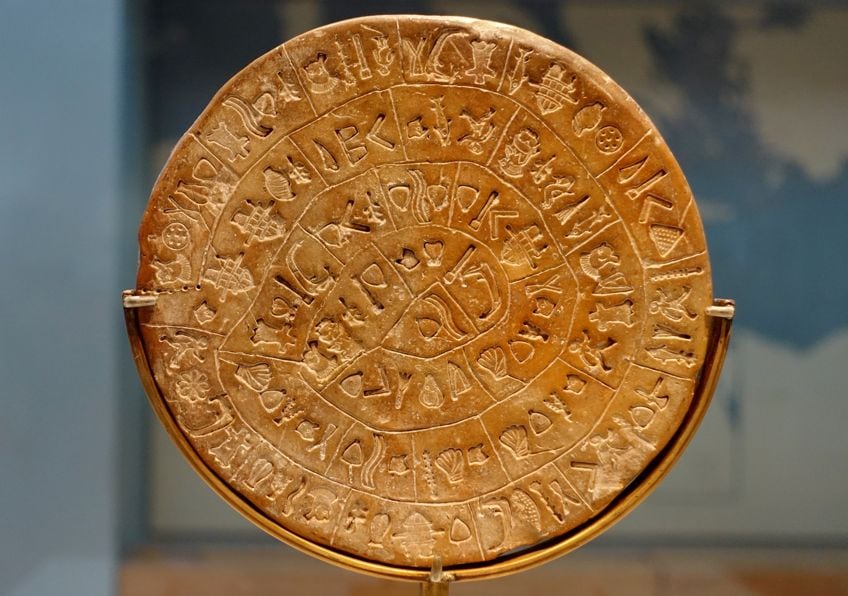

The language employed by the Minoan civilization was Linear A script and Cretan hieroglyphics, which became known as the Minoan language. The gradual decline of civilization began around 1550 BCE and is attributed to various reasons, but with no definitive answer as to why the civilization disappeared. A few theories include the major Santorini eruption and the Mycenaean invasions.

Kamares-style Minoan pottery, Protopalatial Period ( 2100-1700 B.C.); Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Kamares-style Minoan pottery, Protopalatial Period ( 2100-1700 B.C.); Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Minoan society was a mercantile group of people who not only thrived in trade relations but also in local agriculture. The Minoan civilization peaked as they reached the height of trade success with international relations across the Mediterranean. Much of the religious aspect of the culture revolved around women and female deities.

This led scholars to believe, although contested by archaeologists and historians, that the Minoan society was matriarchal since the culture seemed to prioritize female deities and officials over male deities.

The Minoan economy was structured around the system known as palace economy and refers to a broad term for ancient pre-monetary cultures where the strength of the economy depended on the gathering of crops and goods by a central government or religious body, often religion and politics partnering up with one another, to redistribute “wealth” to the rest of the population.

Minoan Art: From the Bronze Age to Foreign Influences

You may wonder what Minoan art looked like or how it played a role in Minoan culture. The Bronze Age, which commenced around 3200 BCE, was an important moment in Minoan history. The early Bronze Age, occurring between 3500 and 2100 BCE was the age of promise and greatness for Crete, which saw the development of commercial networks and the expansion of the upper class. The early Minoan period birthed pottery produced by the Korakou culture, also understood as the early Helladic II culture.

The middle Minoan period saw the construction and expansion of palaces after the early Bronze Age.

Around 1700 BCE, an earthquake or invasion caused some disturbance in Crete, resulting in a few palaces being obliterated. The reconstruction of the palaces took place on a larger scale in the New Palatial period between the 17th and 16th centuries. The late Minoan period saw a major volcanic eruption and the Minoans soon had to rebuild their palaces again. The majority of Minoan palaces and Cretan cities declined by the 13th century with the last Minoan location at Karfi, which became a refuge hub close to the Iron Age.

The art of the Minoans covered both sculpture and painting as seen in the surviving works of Minoan artifacts and frescoes. A few Mycenae shaft tombs contain Cretan imports that convey the role of Symbolism in Minoan culture. The relationships between Egyptian and Minoan cultures are also seen in materials such as papyrus and Minoan ceramics, which were discovered in Egypt. The trade network from the Aegean islands, Mediterranean, and Near East was key to the sharing of knowledge and artistic processes. It is believed that the hieroglyphs of the Egyptians possibly served as an inspiration to the Minoans and incited the development of the Linear A and B writing systems.

The Phaistos Disc (side B) found in the Phaistos archaeological site on July 3, 1908. On display in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete, Greece; Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Phaistos Disc (side B) found in the Phaistos archaeological site on July 3, 1908. On display in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete, Greece; Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Toward the latter stage of the Bronze Age, the Mycenaeans began occupying many Minoan palaces, which sparked the development of the language to an ancient form of Greek called Mycenaean Greek. The cultural development was more of an adaptation of the previous culture as opposed to a completely new society and this pooled into other aspects of the civilization, including art, religion, economics, and bureaucracy.

Minoan paintings and frescoes often featured landscape scenes with a diverse array of subject matter, executed in a variety of media. While pottery featured figurative imagery, the image of bull-leaping was a common subject in painting and sculpture. The human figures that do appear in Minoan art do not indicate whether these figures were royal or simply official and there are no remaining portraits of individuals from which to conclude the varying styles. Minoan art also includes marine fauna and sea creatures like the octopus. Hunting scenes and scenes of warfare were discovered in later works believed to have been executed by Cretan artists for the Mycenaean market or Cretan overlords.

Today, the best collection of Minoan art is located at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Crete.

Minoan Painting

You may be curious as to how this early European civilization created its unique frescoes and wall paintings. The Minoans employed a variety of painting techniques, inspired by other regions in the trade network, which resulted in vivid imagery often depicted in blue, yellow, red, green, and white. Artists also made use of mechanical tools to create advanced geometric patterns and motifs while integrating stylistic elements and detail in their paintings. One unique aspect of Minoan painting to note is that many of the artworks do not display a true sense of perspective and were not overtly technically focused.

The “Blue Boy” or the “Saffron-Gatherer” Minoan fresco from Knossos; Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The “Blue Boy” or the “Saffron-Gatherer” Minoan fresco from Knossos; Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Techniques such as buon fresco and fresco-secco were used in Minoan paintings to maintain the luminosity and preservation of color on the plastered lime walls of palaces. Pigments were often made from minerals and then combined with organic materials to create unique shades.

The art depicted in Minoan frescoes demonstrates not only the culture and lifestyle of the Minoan society at its height but also the ability of the Minoan artists to narrate an event and grant character to the human figures in Minoan paintings.

Prehistoric Crete offers much insight into the daily life of Minoan society as seen in the examples of Minoan frescoes below.

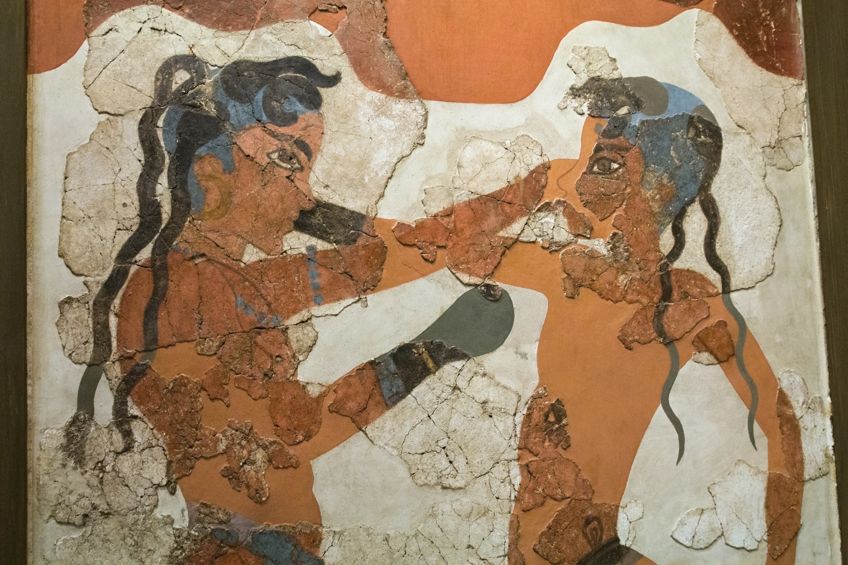

Akrotiri Boxer Fresco (c. 1700 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1700 BCE |

| Medium | Buon fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 94 x 275 |

| Where It Is Housed | Akrotiri, Santorini |

The Akrotiri Boxer Fresco is one of the most famous Minoan frescoes discovered in 1967 and portrays two young boxers in boxing attire. The painting dates back to 1700 BCE, which was just before the major earthquake and volcanic eruption that destroyed numerous buildings in Akrotiri. Luckily for the disaster, many frescoes in certain parts of Akrotiri survived.

Boxing Children fresco, from Akrotiri, Middle Bronze Age (2000-1600 BC); Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Boxing Children fresco, from Akrotiri, Middle Bronze Age (2000-1600 BC); Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What makes this fresco so important is that it provides scholars with an understanding of the preferred cultural activities of Minoans at the time. The young men are also represented with brown skin to illustrate their gender. The young man with jewelry on the left of the fresco is said to hold a higher status than the boy on the right. Among boxing, the Minoans were invested in several other sports, including acrobatics, wrestling, and bull-jumping.

Sports were incredibly important to Minoan society and even formed a part of their religious belief system.

Ladies in Blue (c. 1600 – 1450 BCE)

| Artist(s) | Original: Unknown Reproduction: Émile Gilliéron (1850 – 1924) |

| Date | c. 1600 – 1450 BCE |

| Medium | Painted plaster |

| Dimensions (cm) | 156.2 x 101.6 |

| Where It Is Housed | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

This fresco is a reproduction of the original Minoan painting found in Knossos in 1914. The image depicts three women and is a reconstruction by E. Gillieron, based on the remains of the original. It is not clear as to the full essence of Minoan painting styles and approaches since many frescoes were discovered in fragments and all that remain are possible reconstructions.

Ladies in Blue was created between 1600 and 1450 BCE and illustrates three women against a blue backdrop wearing open blouses, believed to be part of the fashion at the time. The ladies’ faces are portrayed as bright white as they show off their exquisite hairstyles and shapely, graceful figures. The figures appear to be conversing with each other during a court festival or important religious event.

It is believed that these women represent the upper class of Minoan society and may be symbolic of goddesses such as the Snake Goddess or simply noblewoman.

Ladies in Blue Fresco (c. 1600 – 1450 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ladies in Blue Fresco (c. 1600 – 1450 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Minoan art saw a shift in the depiction of the human form or ideal figure in relation to the fashions of the time. According to Minoan iconography, there was a shift in preference from depictions with figures wearing hats to long hair, and eventually complex headdresses, especially in the New Palace era. This may have been a defining statement that singled out noblewomen or women of high stature from ordinary citizens.

Another common stylistic element of Minoan painting is the depiction of figures with narrow waists and sinuous linework, which shows the confidence of the artist’s hand and careful rendering of each figure, according to an ideal. Given that these frescoes were probably executed on wet plaster, the artist would have to be exceptionally skilled at improvisation and integrating the art of chance while painting. The Minoans favored the fluid nature of such approaches and it reflects strongly in their work. This also mirrors the seafaring culture of the Minoan society as seen through the freedom of line work and color.

The original remains of Ladies in Blue can also be found at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum.

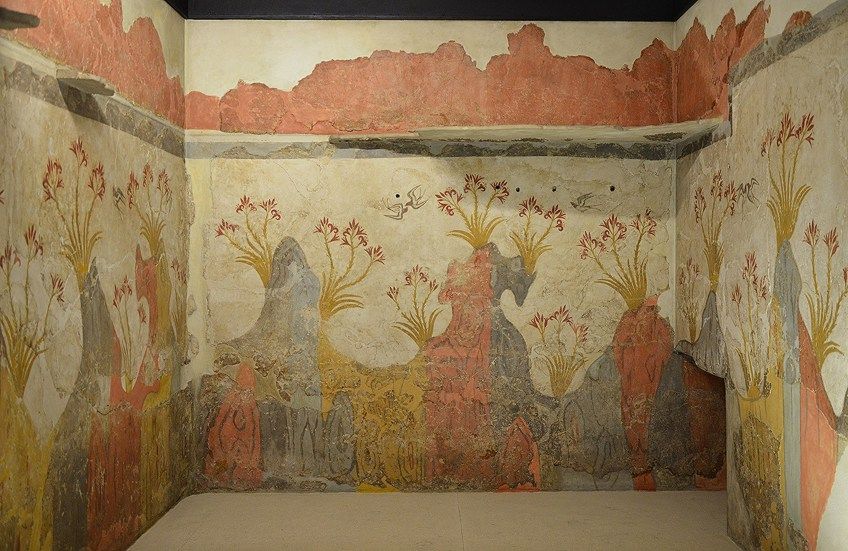

Landscape with Sparrows, Spring Fresco (c. 1650 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1650 BCE |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | Center: 250 x 260 Side walls: 50 x 222; 250 x 188 |

| Where It Is Housed | National Archaeological Museum, Collection of Prehistoric Antiquities, Athens, Greece |

Landscape with Sparrows or Spring Fresco is one of the most famous Minoan wall paintings from Akrotiri, recognized for being one of the first examples of pure landscape painting. The ruins of the painting capture an ancient view of the natural land with such a dream-like quality that nature seemed to have been romanticized.

The Spring Fresco, from Akrotiri, Thera (Santorini), Minoan Civilization, 16th Century BC; Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The painting illustrates a hilly landscape featuring many lilies sprouting from the earth as the sparrows dance in the windy atmosphere above. The wind is highlighted by the sway of the lilies, which adds a sense of movement and rhythm to the room.

Dolphin Fresco (c. 1500 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1500 BCE |

| Medium | Fresco; lime, hematite/ferrous oxide, yellow ochre on dry wall |

| Dimensions (cm) | Information unavailable |

| Where It Is Housed | Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

This famous Dolphin Fresco is one of the most famous surviving artworks from the Neo-Palatial palace of Knossos in Greece. The fresco was discovered in fragments in the East Wing residential quarters of Knossos Palace next to the Queen’s Megaron, as named by Arthur Evans. The fresco was restored by Piet de Jong between 1922 and 1930 and a replica currently stands over the entrance of the north side of the quarter.

This fresco illustrates five larger dolphins in the foreground, surrounded by numerous smaller dolphins in the background, and is a great example of the art style of Neo palatial Minoan art.

Minoan paintings were made on plastered walls and often featured the Egyptian influence of the side profile of a human face with solid bold outlines. Such natural scenes are a characteristic of Minoan art that demonstrate fluidity in motion and an elegant sense of freedom in painting.

So, how do Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes? One of the most frequently asked questions at the forefront of early European art revolves around the actual difference between Egyptian approaches to painting and Minoan practices in art. Egyptian painters of the old kingdom created frescoes using the fresco secco method or dry-fresco technique, which refers to painting on dry-plastered walls.

Dolphins Fresco (c. 1500 BCE); Jebulon, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Dolphins Fresco (c. 1500 BCE); Jebulon, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

On the other hand, the Minoans employed the wet-on-wet fresco technique by applying pigments directly on wet plaster. This gave the Minoan artists an advantage since the wet plaster enabled the pigments in mineral oxides and other pigmented metals to bind to the wall, thus allowing an extended period of preservation.

The flip side of this technique was that it had to be executed quite fast, which meant that such surviving frescoes were probably created by highly-skilled artists of the time.

Hagia Triada Sarcophagus (c. 1400 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1400 BCE |

| Medium | Fresco on limestone |

| Dimensions (m) | 1.375 x 0.45 x 0.985 |

| Where It Is Housed | Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

The Hagia Triada Sarcophagus is the only fully-painted Minoan sarcophagus known to date, which depicts a narrative scene believed to represent burial and sacrificial practice. The Hagia Triada Sarcophagus was discovered in 1903 by Roberto Paribeni at the archaeological site, Hagia Triada in Tomb 4. The tomb belonged to a family from a wealthy Minoan settlement located in Southern Crete. The sarcophagus was crafted from limestone and an additional ceramic coffin. The tomb also contained various ornaments and Minoan artifacts, which led researchers to believe that the tomb belonged to a family of royals.

Hagia Triada Sarcophagus (c. 1400 BCE);Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hagia Triada Sarcophagus (c. 1400 BCE);Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

One of the most visible portions of the fresco illustrates a funeral procession and a libation ceremony with several figures. The left side of the painting shows a woman facing her left and dressed in a fashionable hide skirt with an open shirt. She appears to hold a vessel with both her hands as she pours the liquid into a larger vessel. Another woman is seen dressed in an elaborate robe with a lily crown and carries a pole on her shoulders that is supported by two extra vessels.

The other figures on the left include three adult males painted with bare chests and dressed in hide skirts.

The first two men are seen with bovine statues in their hands and the third man with a small boat sculpture. The men are depicted in the composite profile with their shoulders facing forward and heads set in profile view, which was a borrowed convention from Egypt. The deceased individual in question is represented as a man without feet and positioned as though his body were a sculpture. Behind the deceased man is another ornate structure decorated with running spirals and veined stone as an inlay.

The background of the fresco shifts from blue to white as your gaze wanders over to the left. Here, there is another male figure with a double flute dressed in a short blue garment. In front of the flute player is an altar or offering table with a trussed bull facing the viewer on its side. The bull’s neck is highlighted with streaks of blood pouring from its neck into a vessel on the floor. The two goats stand in line, awaiting their fate as sacrifices.

La Parisienne (c. 1350 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1350 BCE |

| Medium | Buon fresco |

| Dimensions (cm) | 20 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete, Greece |

This famous Minoan painting portrays a young woman with curly hair, dressed in a brightly-colored dress, and is one of the most well-known surviving Minoan wall paintings in history. This rare fresco portrait is one of the few surviving paintings of a woman executed in full color and with great attention to detail. The painting received its title from the popular art historian, Edmond Pottier, who compared the painting to that of a Parisian woman and since then, the painting has been known as La Parisienne.

Many Minoan wall paintings illustrated subjects from everyday life, especially the scenes found at Knossos.

La Parisienne, Knossos, 14th century BC; Heraklion Archaeological Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

La Parisienne, Knossos, 14th century BC; Heraklion Archaeological Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Other subjects featured in Minoan wall paintings include religious themes that celebrate divinity in nature, rituals, processions, cult-like activities, important festivals, Gods and deities, priesthood, and bull-leaping contests. Nature was closely connected to the divine and thus its representation in art was also crucial to paying respect to the divine. Other Minoan frescoes illustrate the flora and fauna of the island of Crete, with imagery of roses, lilies, and animals such as the griffin, dolphins, octopi, and bulls.

One of the striking features of La Parisienne is the woman’s hair with one curl dangling on her forehead and the rest of her hair falling effortlessly down her back. The white skin represented in the painting was inspired by the conventional colors used to represent women as seen in ancient Egypt while men were represented with brown skin. The most Egyptian quality of the painting is the woman’s eye, yet her bright lips are a slight adjustment from the Egyptian influence.

The woman is also dressed in a red and blue striped dress with a sacred knot tied to the back of her dress. The “sacred knot” refers to the looped pieces of fabric tied to the nape of the woman’s neck.

This sacred knot features in one of two paintings of a woman wearing a knot and is believed to be a symbol related to a holy figure or priestess. Other places where the sacred knot was found included seals, pieces of ivory, and painted onto pottery and walls. Minoan art also features a variety of decorative motifs and designs that were used to adorn the ceilings of palaces. Some common patterns included borders with garlands, spiral shapes, and rosettes in rows.

Minoan Sculpture

The majority of Minoan sculptures were considered monumental and this is why there are not many surviving Minoan sculptures from which to assess the development of the early Minoan sculptural style and the transition to larger structures. Minoan sculptors from the early Bronze Age were known to be just as skilled as the artisans from Egypt, especially in the art of stone sculpture.

Minoan plastic rhyton vase from the Prepalatial Period, early Minoan III – middle Minoan IA; ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Minoan plastic rhyton vase from the Prepalatial Period, early Minoan III – middle Minoan IA; ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The end of the third millennium BCE saw the development of advanced stone sculptures in Minoan society that were crafted from refractory stones such as soapstone and sandstone. Highly pigmented stones from Crete such as alabaster, breccias, marble, and different shades of soapstone were the foundations of many stunning vases, which fueled the design and inspiration of Minoan sculptors.

Below, you will find a few interesting Minoan artifacts and sculptures that will enlighten you about the Cretan lifestyle and culture.

Snake Goddess (c. 1600 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1600 BCE |

| Medium | Minoan Majolica |

| Dimensions (cm) | 29.5 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

Sir Arthur Evans uncovered many important Minoan finds during his excavations in Crete, including the statue of the Snake Goddess. This powerful deity is one of the most replicated images in antiquity and was originally discovered in fragments. The Minoan Snake Goddess figurine was restored by both Evans and Halvor Bagge with the addition of an arm, a snake, the goddess’s head, and a cat on her head. Many small artifacts were dedicated to representing kings and Gods but the Snake Goddess figurine stands out the most for her frontal pose. The Snake Goddess figurine portrays the goddess in a pose that is reminiscent of Egyptian and Mesopotamian sculpture and is possibly a combination of the two influences.

Snake Goddess (c. 1600 BC); Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Snake Goddess (c. 1600 BC); Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The figure’s arms bear snakes, which adds a sense of life and movement to the static nature of the goddess’s pose. Upon Evan’s discovery, he assumed the statue to be a goddess yet it may also simply represent a powerful priestess. Another common feature of the representation of women in Minoan art is that most sculptures and paintings portray the women with their breasts exposed, adding a sense of vulnerability and power that the matriarchal society worshiped. The exposure of female breasts was a common practice and seen as a norm in Minoan society.

Kamares Crater Banquet Vessel (1800 – 1700 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | c. 1800 – 1700 BCE |

| Medium | Clay |

| Dimensions (cm) | 45.5 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Heraklion, Crete, Greece |

Housed in the permanent collection of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, this Kamares Crater Banquet Vessel with decorative lilies is an iconic piece that was discovered in Phaistos. The Kamares style was a unique polychrome style that originated in Crete during the proto-palatial era.

The clay vessel is decorated with flowers emerging from the body and is one of the most beautiful sculptural works from Minoan art history.

The vase was sculpted with two horizontal handles, a circular base, and ornate decoration with plastic and painted flowers. The plastic flowers appear to be either lilies or daffodils and are symbolic of the grace of nature. The red curled motifs at the foot of the vase and the handles could be identified as corals given the marine culture of the Minoan society. The vase may have been a royal vessel that was used especially for royal banquets at the Phaistos palace.

Terracotta Vase, Bull’s Head (1450 – 1400 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown |

| Period | Late Minoan II |

| Date | c. 1450 – 1400 BCE |

| Medium | Terracotta vase; painted |

| Dimensions (cm) | 9.5 x 13.9 |

| Where It Is Housed | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

This Late Minoan II terracotta vase was sculpted in the shape of a bull’s head and is recognized as a type of libation vase. A libation vase refers to a vessel that is used for ceremonial or offering purposes, usually to pour beer or water from. The offering, in this case, would be poured through the holes in the bull’s nose and would be topped up via immersion or through a hold on the top of the vase.

The bull is also known as the divine bull and is one of the most venerated creatures of this ancient civilization.

The Minoan civilization drew logic from the natural world and created ritual practices that combined the chaotic nature of the universe with humanity’s ability to triumph over the natural land. Art was considered one of the primary forms through which they could express their relationship with nature.

Terracotta Vase, Bull’s Head (1450 – 1400 BCE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Terracotta Vase, Bull’s Head (1450 – 1400 BCE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The significance of the bull is related to the bull serving as a physical manifestation of an Earth deity. The narrative created with the bull goes back to the Cretan king, Minos who asked Poseidon for a bull for sacrificial purposes. Poseidon granted Minos a white bull, which was so beautiful that Minos did not have the heart to kill it. This angered Poseidon and he cursed Minos’ wife to fall in love with the bull. The product of their love was a minotaur, a half-beast, half-human creature who was imprisoned and later slain by a Minoan warrior, Theseus. The white bull then became a symbol of power and beauty, which was not an earthy creature by nature but an ephemeral creature sent by Poseidon.

Minoan art offers us a glimpse into the origins of European art history, which can inform your viewpoint on the development of artistic processes and the importance of multicultural influences. Minoan art history, or what remains of it, is still a resourceful pool from which one can draw connections between culture, painting, religion, sculpture, design, the economy, international relations, and how these factors shape the way that a civilization prioritized and viewed art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Minoan Art Most Famous For?

Minoan art is most famous for depictions of Minoan culture, religious ceremonies, and marine animals during the Cretan Bronze Age, which occurred between 2000 and 1500 BCE. Minoan art is also famous for its decorative vases, jewelry, stone vessels, and colorful frescoes.

How Do Minoan Frescoes Differ From Egyptian Frescoes?

Minoan frescoes differ from Egyptian frescoes in a variety of visual ways, including the approach to painting. Minoan frescoes were often created using painting techniques that involved the wet-on-wet application of paint and held a sense of two-dimensionality. Minoan frescoes also lacked perspective and utilized a variety of bold, colorful, Mediterranean-inspired colors. Egyptian frescoes on the other hand differed from Minoan frescoes in that the majority of the surviving works were created by artists applying paint directly on dry walls. The Egyptian frescoes are also more three-dimensional and feature elements such as the composite pose in figure drawings. The Minoan artists also focused more on naturalism and fluidity in art.

Which Is the Most Famous Minoan Palace?

The most famous Minoan palace is considered to be the Palace of Knossos, which is located in the archaeological Bronze Age site of Heraklion in Crete, Greece, and is known to be one of the most well-known ancient Minoan settlements, famous for its advanced architecture.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.