Inca Art – The History and Development of Inca Material Culture

Inca empire art is regarded as some of the finest artwork to have been produced in the ancient Americas. Inca art is best represented by Inca pottery, metalwork, and textiles. Although the Inca priests and warriors would often adorn their faces with paint, Inca paintings of portraits only emerged after the arrival of the Spaniards. In this article, we will be looking at the important types of Inca art that were produced, and explore the various Inca artifacts, such as Inca sculptures and clothing, that have provided us with a taste of their rich and ancient culture.

Contents

An Exploration of Inca Art and Inca Artifacts

The ancient Incas left behind a rich legacy of Inca artwork to the world that is as varied, powerful, and innovative as that of any great ancient civilization. Inca artifacts are accompanied by magnificent works of architecture constructed by the Incas throughout their short but significant reign.

Cultural significance and spiritual symbolism abound in Inca empire art and architecture.

Inti Raymi (Festival of the Sun) at Sacsayhuaman, Cusco; Cyntia Motta, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Inti Raymi (Festival of the Sun) at Sacsayhuaman, Cusco; Cyntia Motta, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The History of Inca Empire Art

Most Inca art was based on or influenced by the art of previous South American civilizations, and archeological discoveries have revealed that pre-Inca tribes refined their crafts to an unprecedented level. The Incas defeated a series of older civilizations in the late 14th and early 15th centuries, which were later integrated into their vast empire.

Manco Capac, First Inca, 1 of 14 portraits of Inca kings; Brooklyn Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Manco Capac, First Inca, 1 of 14 portraits of Inca kings; Brooklyn Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Older traditions and creative methods that existed for thousands of years inspired Inca art, such as Lake Titicaca’s early Tiahuanaco civilization, the Wari of the middle Andes, the Chimu and Moche of the northern coast, and many other small communities.

Recuay ceramics; Vassil, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Recuay ceramics; Vassil, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Incas developed artworks that were both beautiful and functional. Because they were adept organizers, art from across the Empire reflect a synthesis of previous styles and methods with the emerging Inca ideals of religion and social order. The Khipu is a famous piece of Inca artistry associated with the Inca Empire’s social administration practices.

These fascinating, intricate threads were recording devices for noting anything that occurred and for keeping track of all of the Empire’s resources.

Inca Empire Art Influences

The Incas imposed conventional Inca designs and patterns on their subjugated people, much as they did on their political subjects. However, the art essentially did not deteriorate in style or quality as a result. The checkerboard pattern is a prominent motif. One reason for pattern repetition was that ceramics and textiles were frequently produced for the kingdom as a tribute or tax.

Thus, these artworks were reflective of individual communities and their cultural history.

Moche gold earmuffs. 1-800 BC. Collection of the Larco Museum. Lima Peru; Larco Museum, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Moche gold earmuffs. 1-800 BC. Collection of the Larco Museum. Lima Peru; Larco Museum, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Just like today’s stamps and coins represent a country’s history, Andean artwork had identifiable themes that either reflected the unique communities who created them, or the dictated patterns of the governing Inca class that ordered them. Yet, the Incas allowed local traditions to preserve their favored colors and sizes. Additionally, talented artisans from the Titicaca area or the Chan Chan region, as well as women who were particularly good at weaving, were sent to Cuzco to make exquisite items for the Inca monarchs.

Stone-carved Inca votive container; Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Stone-carved Inca votive container; Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

It is also worth noting that neither Inca pottery ornamentation nor textiles included depictions of themselves, their ceremonies, their military victories, or popular Andean imagery like demons and half-animal half-human characters.

Inca Empire Art Mediums

Although motivated by the older Chimu civilization’s art and innovations, the Incas developed their own unique style that became an instantly recognizable emblem of imperial domination across their huge territory. Despite intense competitors such as the masters of metallurgy of the Moche civilization, the Incas would proceed to create Inca pottery, textiles, and metal Inca sculptures technically superior to any preceding Andean society.

The Incas generally preferred colorful geometrical patterns and abstract themes depicting birds and animals.

Inca Pottery

Natural clay was used in Inca pottery, but it was strengthened with sand, mica, pulverized rock, and shell to avoid cracks during the burning process. Because there was no potter’s wheel in the ancient Americas, vessels were constructed by hand, starting with a base and then wrapping a loop of clay around it until the object reached the desired size. The edges were then flattened using a smooth stone. Clay molds were used to create smaller and medium-sized pots.

A clay “slip” was applied before burning, and the object was then painted, decorated (often with stamps), or had reliefs inserted.

Aryballos decorated with spondylus; Musée du quai Branly, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR, via Wikimedia Commons

Aryballos decorated with spondylus; Musée du quai Branly, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR, via Wikimedia Commons

The vessels were then burnt in pits, kilns, or open flames using the oxidizing technique to make yellow, red, and cream-colored pottery, or the reduction technique to make black ceramics. Because Inca pottery was intended for a wide range of applications, designs were primarily functional.

The urpu, (a globular jar with a flared lip, long neck, two low short handles, and a pointed base) was a vessel used for storing corn, and it was the most commonly produced. The base point pushed into the earth, stabilizing the pot as corn was fed into it.

Face neck jar, Inca, Ecuador, 1450-1532, ceramic; Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Face neck jar, Inca, Ecuador, 1450-1532, ceramic; Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Urpu were standardized in size based on their content capacity. They were adorned with abstracted plant motifs and geometric patterns, the most frequent of which were dots and zig-zags. Cuzco specimens are more exquisite than others and are painted in a striking black-on-red.

Bowls, tall qeros beakers, huge flat serving plates with animal motif handles, and the paccha are all examples of Inca pottery.

The paccha was a hollow tube shaped like a foot plow, usually embellished with three-dimensional decorations like a maize cob and urpu. The paccha was planted in the ground so that corn beer could be ceremonially poured into it to ensure a successful crop.

Metalwork Inca Sculptures

Jewelry, discs, figures, lime dippers, ceremonial knives, and ordinary items composed of precious metals were manufactured specifically for Inca aristocrats. Gold was thought to be the perspiration of the sun, whereas silver was thought to be the teardrop of the moon. Copper was also a commonly used material, and these metals would have been studded with valuable stones such as lapis lazuli, emeralds, polished bones, and shells. Silver and gold were also inlaid into bronze.

Alloyed metals were cast, hammered, pierced, embossed, studded, and gilded.

Ceremonial knife (Tumi); Metropolitan Museum of ArtGift and Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1974, 1977, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ceremonial knife (Tumi); Metropolitan Museum of ArtGift and Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1974, 1977, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Earspools, earrings, bracelets, pendants, and clothes pins were among the precious metal Inca jewelry items. The Inca nobility drank solely from silver and gold beakers and wore shoes with silver bottoms. Surviving llama and human Inca sculptures discovered at burial sites were either cast or sculpted in incredible life-like detail from up to 18 different sheets of gold. Many religious works were also made of silver and gold, particularly depictions of natural occurrences and significant sites of the Incas.

These artworks depicted the moon, sun, stars, lightning, rainbows, and waterfalls, among other things.

Gold Inca llama figurine; Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Gold Inca llama figurine; Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

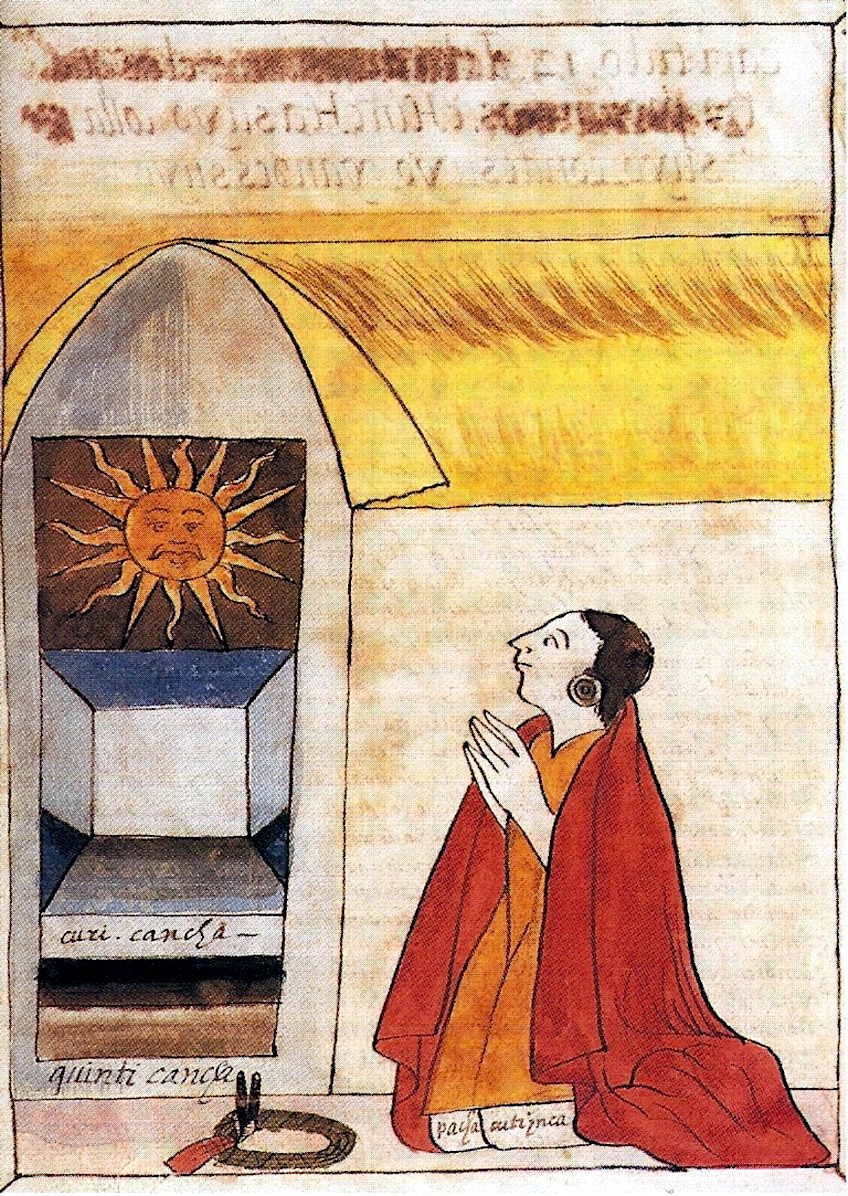

Masks depicting the major gods, such as Mama Kilya, the deity of the moon, and Inti, the deity of the sun, were then put within Inca shrines, although these have now been lost to time.

One of the most renowned lost Inca artifacts is a gold figure of Inti, portrayed as a little seated child and called Punchao, which was held in the Temple of the Sun at Cuzco’s Coricancha holy complex. The stomach of this statue, which had rays protruding from his head and was embellished with gold jewelry, was utilized as a container for the remains of former Inca rulers’ burnt vital organs.

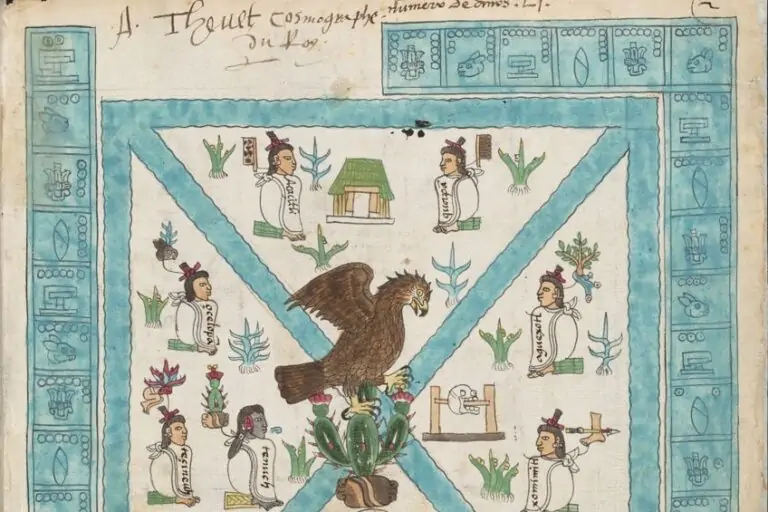

The Inca Pachacútec in the Coricancha Worshipping Inti; Chronicler Martín of Murúa (Cronista Martín de Murúa), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Inca Pachacútec in the Coricancha Worshipping Inti; Chronicler Martín of Murúa (Cronista Martín de Murúa), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Every day, the statue of Inti was transported outdoors to enjoy the sun. The Inca sculpture was moved and concealed after the Spanish invasion, never to be discovered again. There was also a beautiful garden devoted to Inti in the Coricancha. It was entirely constructed of silver and gold. Life-size replicas of llamas, guinea pigs, jaguars, monkeys, birds, shepherds, and even insects and butterflies were created in precious metal.

All that remains of these miracles are a few golden corn stalks, a compelling remnant of the Inca metalworkers’ lost riches.

Inca Textiles

Although there are few specimens of Inca fabrics from the empire’s capital, we do have many cloth samples from the mountains and burial sites due to the dryness of the Andean climate. Furthermore, Spanish chroniclers frequently drew textile patterns and costumes, so we have a decent impression of the types in use. As a result, we have many more samples of textiles than of other crafts like Inca pottery and metallurgy. Finely crafted and highly decorated textiles came to represent wealth and rank for the Inca people.

The fine fabric could be used as both a currency and tax and the finest textiles were among the most valuable of all assets, even more, valuable than silver or gold. Essentially, Inca artisans were the most competent the Americas had ever seen, and the best textiles were regarded as the most valuable offerings of all.

Miniature of an Inca tunic; Museu Nacional, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Miniature of an Inca tunic; Museu Nacional, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As a result, when the Spaniards showed up in the early 16th century, it was textiles rather than metal items that were offered to these guests from another realm as a gift. Textiles appear to have been made by both women and men, although it was a talent required of women of all strata of society.

The best textiles were manufactured at Cuzco by male artisans known as qumpicamayocs.

Spinning was performed with a drop spindle, which was usually made of wood or ceramic. Cotton (particularly in the eastern lowlands and along the coast) or alpaca, llama, and vicuna wool, which may be particularly fine, were used to make Inca textiles. Only the Incan king could own vicuna and produce goods crafted from the super-soft vicuna wool. Maguey fibers were also used to make rougher fabrics.

Making Peruvian Inca textiles; Jae, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Making Peruvian Inca textiles; Jae, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Yellow, green, orange, red, purple, black, and white were the primary colors utilized in Inca textiles. Natural dyes collected from rocks, plants, insects, and mollusks were used to produce these colors.

Each of the colors had its own significance. For instance, the color red was associated with conquering, governance, and blood. The Mascaypacha, the Inca state emblem, symbolized this, with each thread of its scarlet tassel representing a conquered nation. Green signified rainforests, the people who lived in them, ancestry, rain, and the agricultural boom that resulted from tobacco and coca.

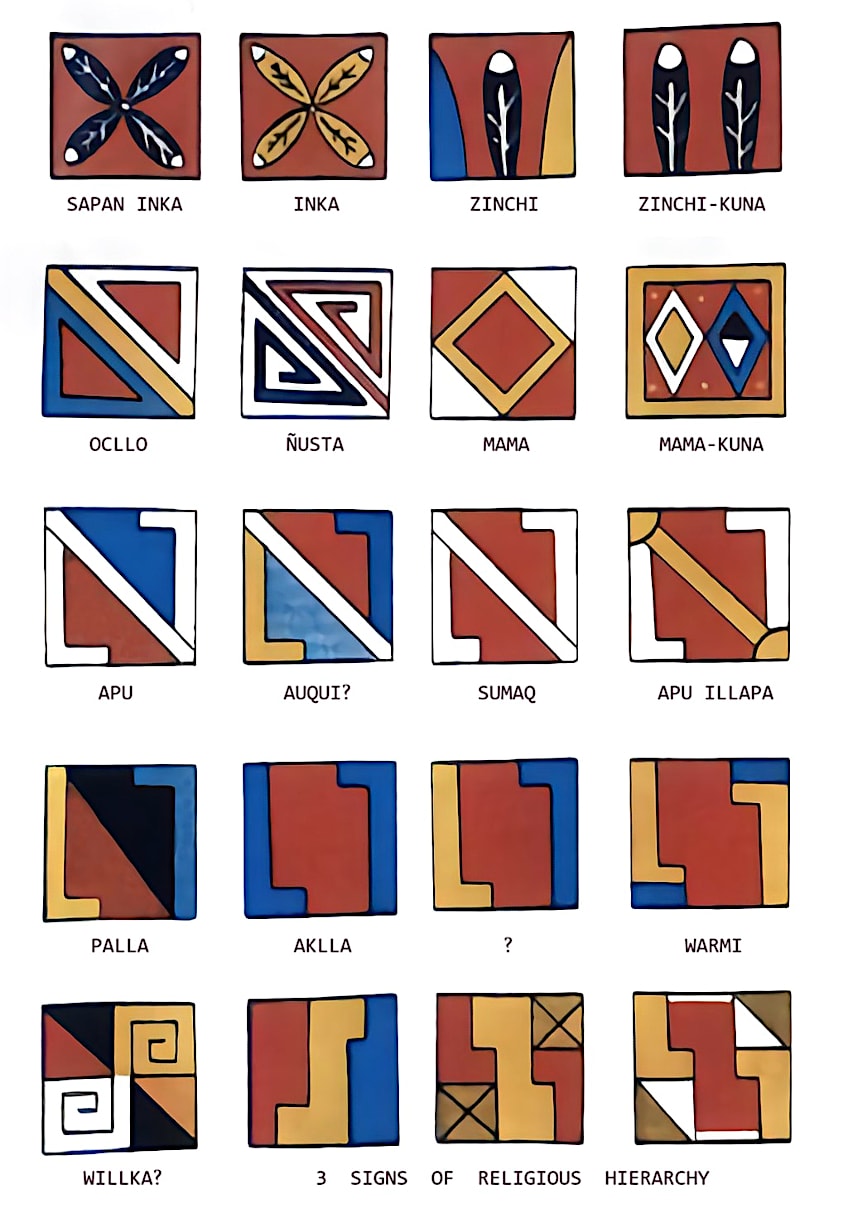

Some Inca Tokapu (symbolic motifs); Yuraq-yaku1, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Some Inca Tokapu (symbolic motifs); Yuraq-yaku1, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Yellow may represent maize or gold, but black represented both creation and death. Purple, like the rainbow, was regarded as the first color and was linked with Mama Oclla, the Inca race’s founding mother. Aside from weaving designs with colored strands, other techniques used included tapestry, embroidery, layering multiple layers of cloth, and painting – either by hand or with wooden stamps. The Incas preferred abstract geometric patterns, specifically checkerboard themes that repeated patterns throughout the cloth’s surface.

Certain designs might have also been ideograms.

Sleeveless Inca tunic; Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sleeveless Inca tunic; Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Non-geometrical themes included felines (particularly pumas and jaguars), snakes, llamas, birds, marine animals, and vegetation, which were frequently depicted in abstract form. Clothes were basically patterned, with square motifs at the fringes, waist, and a triangle defining the neck. Brocades, tassels, feathers, and beads made of valuable shells or metal could be used to embellish textile items. Precious metal strands could be weaved into the fabric as well.

These clothes were designated for the royal family and nobles since the feathers were mainly from condors and rare tropical birds.

Inca Paintings

Throughout the Inca empire period, Cuzco was an important center of creative innovation. Inca painting mainly consisted of murals and decorative designs on stone, and reflected Inca textile design in terms of palette and imagery.

Pre-Columbian Inca Chucu painted stone plaque; Unknown, photo by auctioneer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Pre-Columbian Inca Chucu painted stone plaque; Unknown, photo by auctioneer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Following the Spanish conquest, Spanish artists taught the native Inca artists their skills. Native painters had learned European styles, methods, and compositional designs within just 50 years following the invasion and were creating portraits, narrative, and religious works.

Prior to the invasion, the Inca had no portrait painting tradition similar to the European practice. They adopted it in order to be able to honor their forefathers and their independent heritage.

Viracocha, Eighth Inca, 1 of 14 portraits of Inca kings; Brooklyn Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Viracocha, Eighth Inca, 1 of 14 portraits of Inca kings; Brooklyn Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Depictions of Inca monarchs in the European style were cherished by colonial aboriginal nobles as proof of their aristocratic forefathers all through the colonial era. The Spanish invaders’ trust was undermined after a number of rebellions by Peruvian Indians in the late 1700s. Inca paintings were outlawed and many were burned.

When Peru earned independence from Spain in 1821, the Inca portraits regained popularity, particularly among visitors to Peru, which was another reason the paintings vanished from the region.

Inca Architecture

The Incas’ most significant legacy is their architecture, as they were outstanding builders. Their incredible capacity to construct monuments without the use of concrete is seen in Machu Picchu, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Despite being barely 50 miles from Cusco, the invaders did not find it, and it has endured all these years.

While stone was more abundant in the Andes, visitors to the shore might find remains constructed of adobe walls.

Precision Inca stonework

Precision Inca stonework

The trapezoid is the most common form, and its buildings used to be rectangular. One of the most intriguing aspects of Inca architecture is its relationship to agriculture. Because their lands used to be mountainous, they built terraces to increase the amount of ground available for cultivation. They also developed their own unique road system, roadways, rope bridges, and rest areas.

However, most of them have now vanished, but there is one way to Machu Picchu that still remains today.

Inca architecture at Machu Picchu

Inca architecture at Machu Picchu

Many have wondered how the Incas were able to create such beautiful structures without the use of the wheel or contemporary technologies.

Their structures have endured 500 years in an earthquake-prone zone and served as the foundations for many modern structures. The structure of its society and workers was one of the explanations Inca architecture was effective. They were able to build their workforce to the enormous numbers required to erect such labor-intensive structures. The strongest men were picked, and it was a privilege to be a part of the crew as they built temples for the Incan Gods.

Inca Body Art

The early cultures of South and Central America were concerned with personal hygiene and devised a variety of decorations to adorn the body. Among all South and Central American cultures, decoration denoted social position. The Incas properly cleaned themselves before decorating themselves. The Incas bathed regularly, and the affluent soaked in heated mineral water channeled from hot springs into their own personal bathhouses.

Portrait jar in the form of a human head with a painted face; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait jar in the form of a human head with a painted face; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

These early Americans decorated themselves in a range of ways. Some body adornments were permanent, however, less permanent ornamentation, like body paint, was worn on rare occasions to denote the wearer’s rank. The Incan women did not paint their bodies, but Inca men and priests, like the Mayans, utilized paint to denote their status on their arms, faces, and legs.

Inca Jewelry

The Incas also produced complex feather ornaments for Incan males, such as headbands with feather crowns, collars for their necks, and chest wraps. Furthermore, affluent Inca males adorned their chests with big silver and gold pendants, disks affixed to their shoes and hair, and rings around their wrists and arms. Incan women were only ornamented with a tupu, a metal fastener for their cloak. The tupu’s head was adorned with paint or gold, silver, or copper bells.

Inca jewelry, Ethnological Museum, Berlin, Germany; User:FA2010, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Inca jewelry, Ethnological Museum, Berlin, Germany; User:FA2010, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Inca rulers donned woven caps with gold and wool plumes or tassels and colorful feathers. The majority of the Inca artifacts and golden jewelry were plundered, melted, and transferred to Spain by the Spanish invaders. The majority of the objects on display in museums were discovered by archeologists at burial grounds. They reveal much about the significance and function of jewelry in the Inca culture.

Gold was abundant throughout the Inca Empire and was utilized to produce Inca artifacts and jewelry.

Above everything else, Inca art was functional. The Incas were an artistic people who utilized natural materials and mixed them to create numerous aesthetic shapes in functional ways. Much of their creative expression was employed in everyday living and had religious significance. Because they did not understand science, they had to attribute powers to natural occurrences such as rocks, water, animals, or anything else found in nature, and the best technique to worship was to combine their greatest creative works in their gifts to the gods.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Art Did the Incas Make?

There are several art mediums that the Incas were very good at producing. Of course, they are very well-renowned for their weaving skills and are often considered to have been the best on the continent. However, it was not just their weaving that they were known for and Inca art is also represented by their amazing Inca pottery, textiles, architecture, jewelry, and metalwork Inca sculptures.

Did the Incas Produce Paintings?

Traditionally, the Incas used paint to adorn their bodies on special occasions. However, after the arrival of the Spanish, many of the local artists learned how to paint and created works of art such as portraits. In this way, they were able to portray their kings and thereby document and share their traditions, heritage, and legacy. It is believed that the local artists had mastered all of the traditional western art styles within 50 years of the arrival of the Spanish.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.