Battle of Bunker Hill – First Signs of American Strength

Why was the Battle of Bunker Hill important, and who won the Battle of Bunker Hill? The Battle of Bunker Hill was an important early battle of the American Revolution. Although the British side ultimately won the battle, it was a huge psychological victory for the American colonists because it demonstrated that they could fight well against the British army. Let’s explore this significant moment in American history in greater depth, as well as answer your questions relating to this conflict, such as “where was the Battle of Bunker Hill fought?”.

Why Was the Battle of Bunker Hill Important?

| Name of Battle | Battle of Bunker Hill |

| Name of Associated War | American Revolution |

| Date of Battle | 17 June 1775 |

| Location | Charlestown, Massachusetts, United States |

| Combatants | American and British |

This particularly fierce battle confirmed that there would be no reconciliation possible between the American colonies and England. The British may have won the battle tactically, yet it had proven to also be a very sobering encounter. The English experienced twice as many casualties as the Americans and lost a large number of troops. Following the battle, the patriots retired to their position outside Boston’s perimeters.

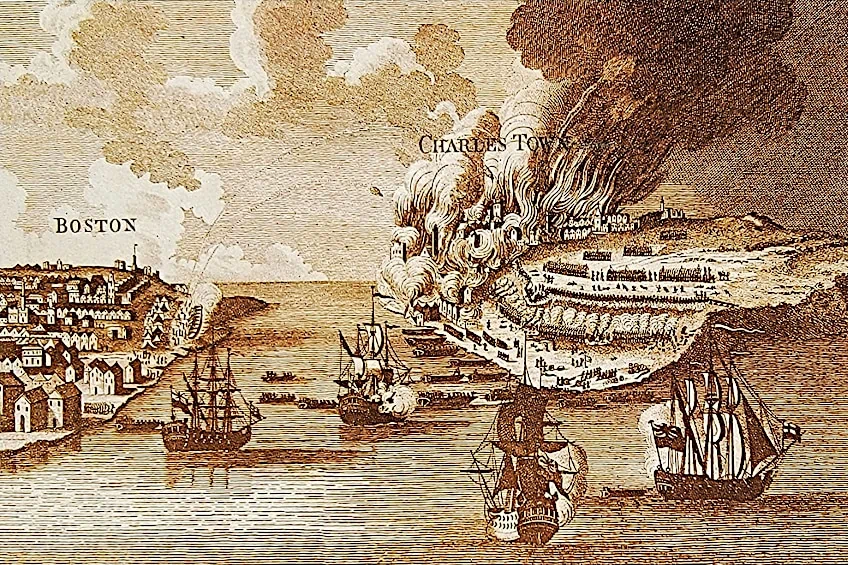

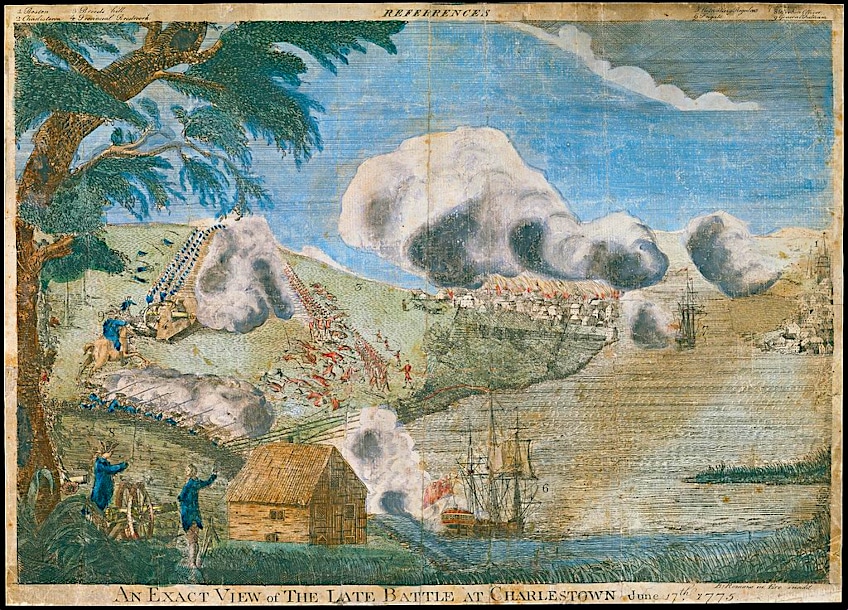

An Exact View of the Late Battle at Charlestown, June 17th 1775 by Bernard Romans (c. 1775); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

An Exact View of the Late Battle at Charlestown, June 17th 1775 by Bernard Romans (c. 1775); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Historical Context of the Battle of Bunker Hill

By early 1775, hostilities between England and the American colonies had reached a boiling point. The colonists started to prepare for battle, while the British stocked up on cannons and gunpowder in preparation for an uprising. It finally ended up reaching the towns of Concord and Lexington. The British fled to their base in Boston following that historic engagement, and the local militia planned for possible future British invasions. Militia members traveled from New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Vermont to defend Boston.

General Sir Thomas Gage, the British Commander-in-Chief, was urged to put an end to the colonial revolt. He had received reinforcements by June and was poised to begin a new strategy.

Portrait of General Thomas Gage by Jeremiah Meyer (c. 1775); Jeremiah Meyer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of General Thomas Gage by Jeremiah Meyer (c. 1775); Jeremiah Meyer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The British intended to mount an attack on the heights to the south and north of Boston. But information regarding the raid was leaked, and a team of 1,000 Connecticut and Massachusetts troops gathered to protect a hill in Charlestown, resembling more of an armed mob of people than an organized military formation. There were both slaves and free African Americans among the defenders as well.

Causes of the Battle of Bunker Hill

Every battle and war occurs because of various factors, including ideological, economic, and political factors. The Battle of Bunker Hill is no exception and many of the factors that resulted in this battle stemmed from the overarching Revolutionary War that it was a part of. This battle was just one in a succession of battles between the American colonials and the British rulers, which all sought to free America from British rule.

Political and Economic Factors

The Americans had already been unhappy with the colonial rule for a considerable amount of time due to feeling unrepresented in government and constantly being inundated with unfair taxes. Their grievances also included the increasing presence of British soldiers in the colonies and the implementation of restrictive trade regulations. Due to their shared grievances, the various colonies began to unite and communicate their ideas of revolution aided largely by the Committee of Correspondence. Political leaders like John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and Thomas Paine were instrumental in galvanizing opposition against British rule and organizing support for American independence.

The British regulations on trade favored British merchants and manufacturers at the ultimate expense of the colonists. These limitations, among them prohibitions on colonial trade with other nations and mandates that specific items be purchased from the United Kingdom, harmed the colonial economy and exacerbated colonial dissent.

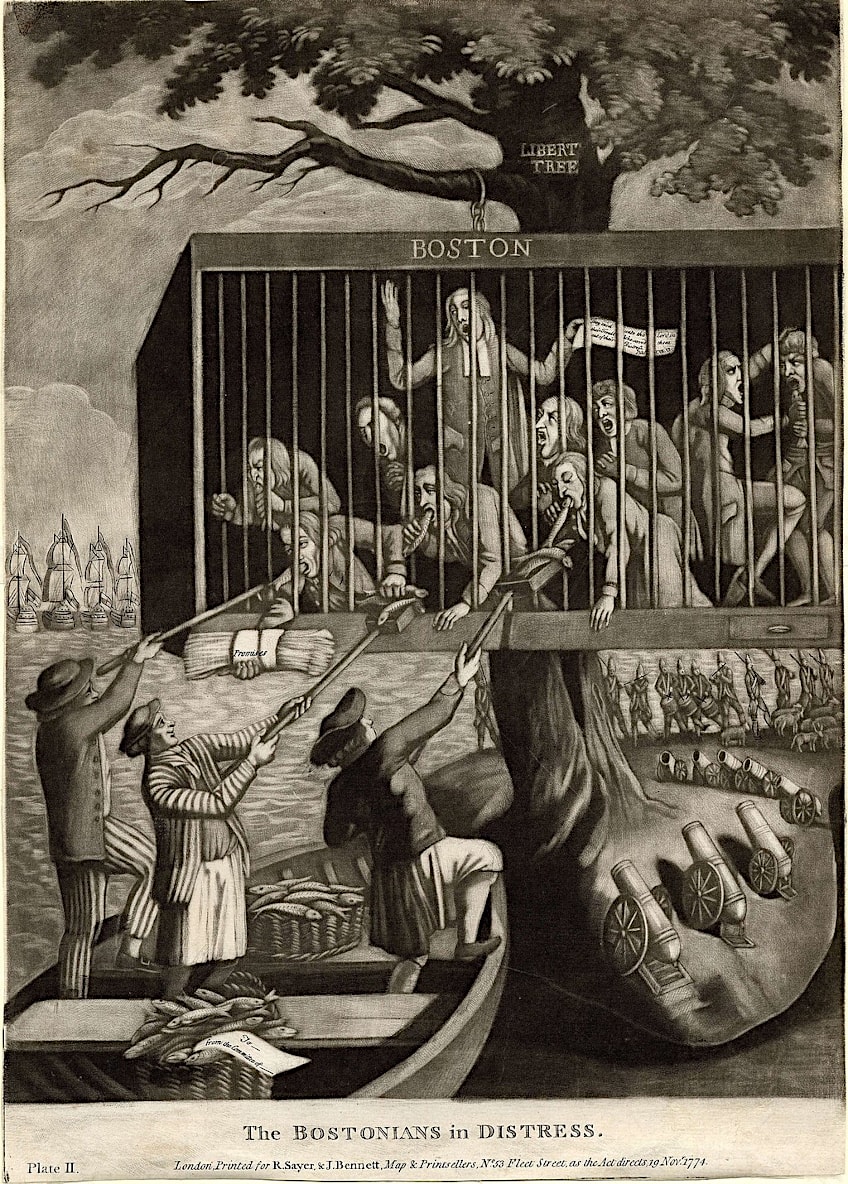

The Bostonians in Distress by an unknown artist (1774). This satire of the closing of the Port of Boston in 1774 shows the English artillery aimed at the city by British General Thomas Gage to cut the city off and starve its inhabitants; British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Bostonians in Distress by an unknown artist (1774). This satire of the closing of the Port of Boston in 1774 shows the English artillery aimed at the city by British General Thomas Gage to cut the city off and starve its inhabitants; British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The British government pursued a mercantilist policy in order to optimize the economic advantages of the British Empire. The American colonies were supposed to supply raw resources and markets for English goods under this policy, and they were barred from creating their own industrial enterprises. This policy significantly hampered the colonies’ financial growth and increased their feelings of economic dependence on Britain.

Ideological and Religious Factors

The works of the thinkers of the Enlightenment, who asserted that everyone ought to be granted the right to liberty, life, and property and that governments should be founded on the authorization of the people, had an impact on many colonists. Many colonists considered themselves ethical people dedicated to the greater good, and they felt that the British government was corrupted and acted in their own best interests.

Many colonists considered the British authority to be unjust and repressive, and they felt it was their responsibility to oppose such oppression. They considered themselves liberty defenders, with the right to fight against an administration that infringed on their basic human rights.

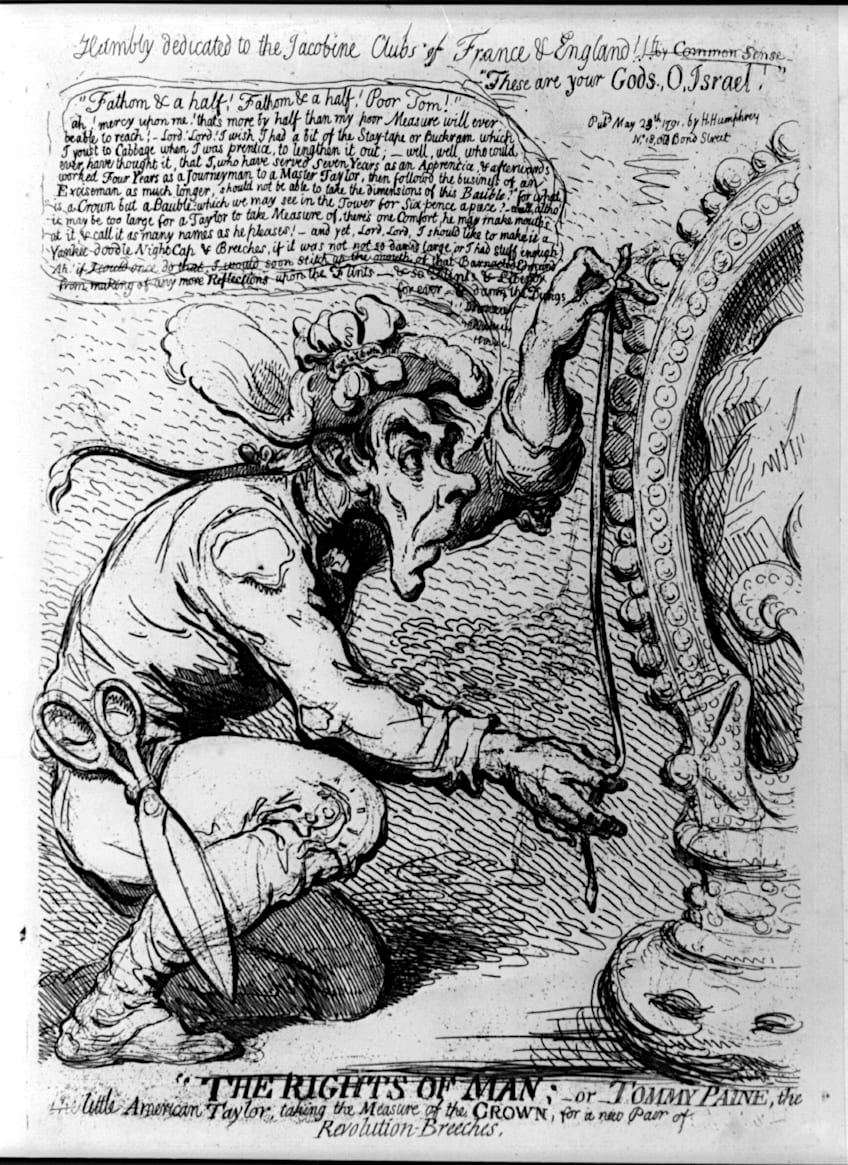

British cartoon satirizing Thomas Paine’s ideas of human rights with the logo: The rights of man; or Tommy Paine, the little American taylor, taking the measure of the crown, for a new pair of revolution-breeches by an unknown artist (1791); British Cartoon Prints Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

British cartoon satirizing Thomas Paine’s ideas of human rights with the logo: The rights of man; or Tommy Paine, the little American taylor, taking the measure of the crown, for a new pair of revolution-breeches by an unknown artist (1791); British Cartoon Prints Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The American Revolution also contributed to the colonists’ sense of national sense of self, as they started thinking of themselves as Americans instead of just British subjects. The collective sense of identity was founded on their shared experiences and beliefs, and it contributed to the colonists’ unity in their defiance of British rule. Even though religion wasn’t the root cause of the American Revolutionary War, it did influence some American colonists’ mindsets and views.

Religious groups such as Baptists, Quakers, and Presbyterians who had faced oppression and discrimination in Europe found refuge in the colonies. These groups enjoyed greater religious freedom in the colonies and had the opportunity to practice their beliefs more openly. Many of their views on individual rights were shaped by their experiences with religious opposition.

Before the Battle

The huge number of soldiers assembled on the outskirts of Boston concerned General Thomas Gage and his newly acquired generals, Henry Clinton, William Howe, and John Burgoyne. The Patriots advanced to Breed’s Hill on the Charlestown peninsula on the 15th and 16th of June, where they established a fortified position that prompted a British reaction. New Hampshire’s General John Stark recognized that the fortified position’s left flank was open along the Mystic River’s southern bank.

General John Stark by Jon Rogers (1889); Joe Mabel, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

General John Stark by Jon Rogers (1889); Joe Mabel, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Stark and his soldiers erected an improvised split rail barricade to thwart any encircling maneuver by the English forces. The British officers were taken aback when they saw what had been built in a single evening. Gage then knew that it was time to act.

The Battle of Bunker Hill

Gage and his generals directed British grenadiers and regulars to make their way across Boston Harbor and exit in lower Charlestown, where he intended to thwart the mob with an assault. As the British advanced, the exhausted but tenacious soldiers inside their hastily constructed defenses remained vigilant. King George’s forces, under the command of General William Howe, mounted Breed’s Hill in an outstanding battle line.

Annotated version of a 1775 engraving by Paul Revere depicting the Battle of Bunker Hill (1775); Paul Revere, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Annotated version of a 1775 engraving by Paul Revere depicting the Battle of Bunker Hill (1775); Paul Revere, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As they advanced, tradition has it that William Prescott, an American officer warned his soldiers not to waste their gunpowder, shouting, “Don’t shoot until you see the whites of their eyes”. When the British soldiers approached the redoubt, the Americans launched a ferocious barrage, resulting in an all-out bloodbath.

“They advanced towards us with the intention of swallowing us up”, one patriot later recounted, “but they discovered a chokey mouthful of American soldiers”. As the British fled to their positions, many of them were slaughtered. The British then rushed up the hill yet again, trampling over the remains of their fallen and injured friends who lay “as dense as sheep in a fold,” and were met with another heroic barrage. Finally, the British succeeded in breaching through the Patriot fortifications on the third attempt, just as the Americans ran out of gunpowder. Inside the fortification, there was intense hand-to-hand combat. The British won the battle, but it was at a substantial cost.

The Aftermath of the Battle of Bunker Hill

While the British had won the battle, it was at a very high cost: they sustained 1,054 casualties (226 killed and 828 injured), with officers accounting for a disproportionate share of the deaths. The casualty total was the greatest for the British in any particular battle during the entire war.

General Clinton wrote in his journal, “Just a few more such successes would have swiftly put a halt to English rule in America”.

Among the British killed and injured were 100 commissioned officers, representing a sizable proportion of the British officer corps in the colonies. The majority of General Howe’s field personnel were killed in the battle. Colonial losses totaled 450 people, 140 of whom died. The majority of colonial fatalities occurred during the evacuation. Colonial Major Andrew McClary was regarded as the highest-ranking individual slain in the conflict; he was the last man killed in the battle when he was struck by a cannon on Charlestown Neck. Fort McClary was subsequently dedicated in his honor in Kittery, Maine.

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775 by John Trumbull (1786); John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775 by John Trumbull (1786); John Trumbull, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The death of Dr. Joseph Warren, though, was seen as a substantial loss for the Patriot cause. He held the position of the President of the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts and had been promoted to Major General on the 14th of June. When he worked as a volunteer soldier three days later at Bunker Hill, his appointment had not yet taken place.

Only 30 men were captured by the British. The majority of them were severely wounded and 20 died while imprisoned. The colonists also lost a large number of shovels and other digging gear, as well as most of the cannons they had carried to the peninsula.

Political Consequences

When word of the conflict reached the colonies, it was acknowledged as a colonial defeat since the enemy had gained ground and suffered substantial fatalities. George Washington, the new leader of the Continental Army, was returning to Boston when he learned of the fighting in New York City. The reports included some incorrect casualty statistics, but they still gave Washington hope that his troops could potentially win the war.

The Massachusetts Committee of Safety wanted to replicate the type of propaganda success it had achieved after the battles of Lexington and Concord, so it hired a battle report to be sent to Britain. Yet, their report was not received in England before Gage’s formal account arrived on the 20th of July.

His report sparked debate between the Whigs and Tories, but the casualty figures worried the military authorities and prompted many to reconsider their positions on colonial military strength. King George’s stance on the colonies worsened, and the developments may have influenced his refusal of the Olive Branch Petition, the last meaningful political endeavor at reconciliation which had been put forward by the Continental Congress.

Tory majority member, Sir James Adolphus Oughton, wrote to Lord Dartmouth of the colonies, “The quicker they begin to suffer distress, the quicker will the Crown’s control over them and the bloodshed will end”.

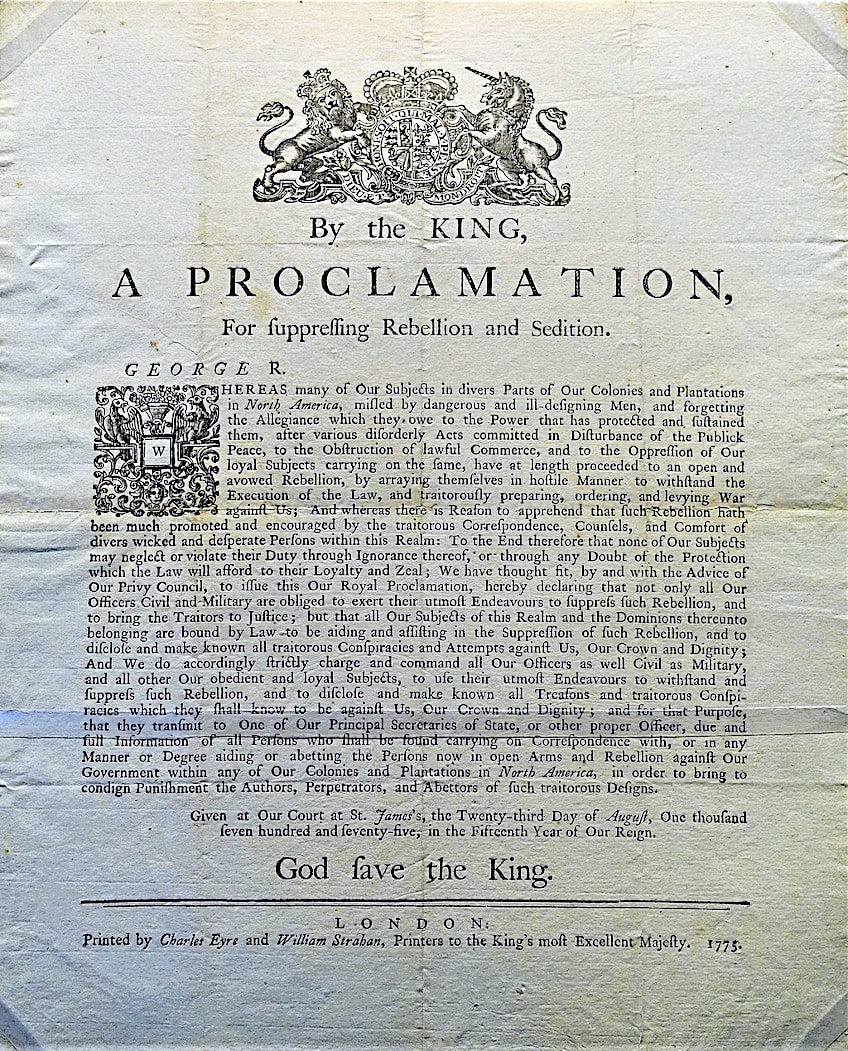

Proclamation of Rebellion, August 23, 1775; Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Proclamation of Rebellion, August 23, 1775; Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In reaction to Gage’s findings, the Proclamation of Rebellion was released about a month later. This strengthening of the British attitude boosted previously sluggish enthusiasm for freedom among Americans, particularly in the southern colonies. Gage’s findings had a more immediate impact on his professional life. He was fired three days after the findings were received, but General Howe wasn’t able to replace him until October 1775. Gage issued an additional report to the British Cabinet, repeating previous concerns that “a large army must at some point be put to use to eliminate these people,” which would necessitate “the employment of foreign troops”.

Historical Analysis of the Battle of Bunker Hill

Years later, after General Israel Putnam had passed away, General Dearborn wrote a report of the conflict in Port Folio, a magazine. In it, he accused General Putnam of inactivity, incompetent leadership, and inability to deliver supplies during combat, sparking a great debate among war historians and veterans.

Major-General Henry Dearborn by Gilbert Stuart (1812); Gilbert Stuart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Major-General Henry Dearborn by Gilbert Stuart (1812); Gilbert Stuart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The viciousness of the attack in the report surprised people, prompting a strong response from Putnam supporters, notably Abigail and John Adams.

Dearborn’s attack drew a lot of media coverage because he was in the midst of a lot of his own controversies at that point in time. He had been stripped of one of the highest commands during the War of 1812. The United States Senate rejected President James Monroe’s recommendation for him to be Secretary of War, making it the first time the Senate has voted against accepting a presidential cabinet candidate.

Colonial Forces’ Disposition

General Ward oversaw the colonial soldiers, with Colonel Prescott and General Putnam directing in the field, yet they often acted autonomously. This was clear in the early phases of the war when a tactical choice with strategic ramifications was taken. Colonel Prescott and his men reportedly defied orders by fortifying Breed’s Hill instead of Bunker Hill. Breed’s Hill fortification had been more militarily aggressive; it would have brought offensive weaponry nearer to Boston, posing a direct threat to the city. It also put the men there at risk of being confined, as they were unlikely to be able to resist British attempts to bring in troops to seize Charlestown Neck. If the English had taken that step, they could have won with many fewer casualties.

Map showing the arrangement of forces during the battle of Bunker Hill (also known as the Battle of Breeds Hill for its actual location); Charlies E. Frye, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Map showing the arrangement of forces during the battle of Bunker Hill (also known as the Battle of Breeds Hill for its actual location); Charlies E. Frye, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The colonial fortifications were hurriedly constructed; it wasn’t until the next day that Prescott realized the redoubt could be readily flanked, necessitating the quick erection of a rail fence. In addition, the colonists lacked enough soldiers to defend against the west. Manpower was another issue on Breed’s Hill. The lines of defense were thin near the northernmost point of the colonial positions and might have been readily attacked by the British (who had already arrived) if supplies hadn’t shown up in time. The colonial forces’ front lines were typically managed well, but the situation behind them was severely chaotic, owing to a poor chain of communication and logistical organization.

“It seems to me that there has never been greater disarray and less leadership”, one analyst remarked. Only a few of the militias were directly under Putnam and Ward’s leadership, and several commanders defied orders by staying at Bunker Hill instead of contributing to the defense of Breed’s Hill once battle commenced. Desertion became a persistent concern for colonial troops once the battle started. There were barely around 700 to 800 soldiers remaining by the time of the third British attack, with only 150 soldiers left in the redoubt.

Colonel Prescott believed that if the troops in the redoubt had been bolstered with additional men, or if additional weapons and gunpowder had been carried forward from Bunker Hill, the subsequent attack would have been resisted. Despite these challenges, the retreat of the colonial forces was largely well-managed, with the majority of their wounded being recovered, and received acclaim from British generals such as Burgoyne. Yet, the pace of the departure forced them to abandon their weapons and entrenching gear.

The midnight march – the American troops, under Colonel William Prescott, taking possession of Breed’s Hill on the night of June 16th, 1775 by J.B. Forrest, J.N. Gimbrede, H.B. Hall, John Hill, et al; Scan by NYPL, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The midnight march – the American troops, under Colonel William Prescott, taking possession of Breed’s Hill on the night of June 16th, 1775 by J.B. Forrest, J.N. Gimbrede, H.B. Hall, John Hill, et al; Scan by NYPL, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

British Forces’ Disposition

Once the fortifications on Breed’s Hill were discovered, the British leadership moved cautiously and slowly. The soldiers were prepared to begin the assault around 2 p.m., nearly 10 hours after the Lively had begun firing. This sluggish pace allowed the colonial forces plenty of opportunity to fortify flanking positions which would have been inadequately defended and exposed otherwise.

While an encircling maneuver to take possession of Charlestown Neck would have given them a more swift and resolute victory, Howe and Gage thought that a frontal assault on the fortifications would be a simple task. Yet, the British leadership was overly hopeful, assuming that “two regiments were adequate to defeat the province’s strength”.

The Battle of Bunker Hill by Winthrop Chandler (c. 1776-177); Winthrop Chandler (1747-1790), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Bunker Hill by Winthrop Chandler (c. 1776-177); Winthrop Chandler (1747-1790), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The artillery barrage that was supposed to precede the offensive did not take place because the field guns were given the incorrect caliber of ammunition. Arriving in the field, Howe repeatedly chose flanking assaults against those on the colonial left to weaken the force assaulting the redoubt. The British formations, organized in long lines and weighted down by superfluous heavy gear, were not suitable for an effective attack; much of the troops were instantly susceptible to colonialist fire, resulting in significant casualties in the opening onslaught.

When officers chose to focus on unleashing repeated volleys that were merely swallowed by the excavations and rail fences, the vitality of any British offensive was further diminished.

Battle of Bunker Hill by Howard Pyle (c. 1897); Howard Pyle, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle of Bunker Hill by Howard Pyle (c. 1897); Howard Pyle, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When the soldiers formed in deep columns, they were told to leave all unneeded equipment behind, the assaults were to be at the point of the bayonet, and the encircling maneuver was only a deception. Following the peninsula’s capture, the British held a tactical edge that they should have used to force their way into Cambridge. General Clinton recommended this to Howe, but Howe rejected it because he had just commanded three assaults with significant casualties, including the majority of his field commanders. To Howe’s detriment, colonial military leaders gradually identified him as a timid decision-maker. Following the Battle of Long Island, he held another tactical advantage that could have placed Washington’s army under his control, yet he once again hesitated to act.

The Battle of Bunker Hill might not have been a victory for the American colonials, but it was barely perceived as one by the British either. In fact, even though the Americans technically lost the battle, it went a long way to showing them just how capable they were at fighting against the British soldiers. It would give them the much-needed courage to fight the rest of the American Revolutionary War.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Won the Battle of Bunker Hill?

The Battle of Bunker Hill occurred between General William Howe’s British Army and Colonel William Prescott’s Colonial forces. Although the British officially won the action by capturing the hill, they sustained huge casualties, notably a significant number of officers, while the Colonial forces managed to inflict devastating losses on the British. The battle is regarded as a psychological triumph for the Colonial forces because it demonstrated their capacity to stand up to the British, which at that point and time was regarded as the strongest military might in the entire world.

Where Was the Battle of Bunker Hill Fought?

The Charlestown Peninsula, situated across the Charles River from Boston, Massachusetts, was the site of the Battle of Bunker Hill. The hill where the fight took place was, in fact, Breed’s Hill, but it was mistaken for Bunker Hill, a more elevated and conspicuous hill nearby. Despite the inaccurate title, the conflict is still referred to as the Battle of Bunker Hill.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.