Roman Artifacts – 10 Famous Masterpieces From Ancient Rome

The story of the Roman Empire, which spanned hundreds of years and numerous continents, is documented through the ancient Roman artifacts left behind by its residents. The ancient Romans merged previously unprecedented military prowess with an equally zealous dedication to public artworks, which functioned as both state propaganda and a means of commemorating diplomatic and military achievements. The Greeks had a massive influence on Roman art, and their influence can be seen in many famous Roman artifacts. However, differences in Roman culture, taste, and building methods meant that while they admired and copied the Greeks, Roman art and architecture developed an aesthetic entirely of their own. Today we will explore some of the most famous Roman artifacts that have been discovered.

Famous Roman Artifacts

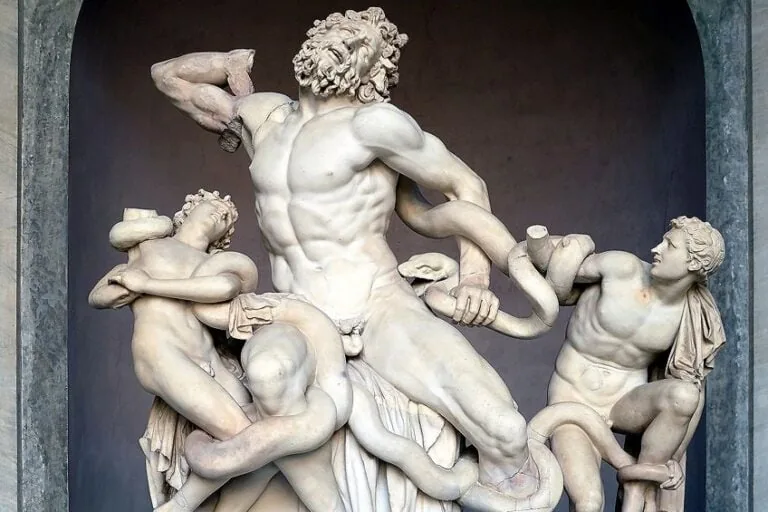

Despite the fact that the Romans defeated the Greeks in 146 BCE, military success was not supported by cultural surrender. Instead, wealthy Romans clamored for replicas of famous marble statues by talented Greek artisans like Praxiteles. However, most Roman sculptors never gained such fame. Because of the workers’ low-class standing and the prevailing demand among Romans for artworks by Greek masters, their reproductions were frequently left unsigned.

Many of the most famous Greek sculptures are now only available as Roman replicas.

The Romans left their imprint on the medium of sculpture by elevating portraiture to unparalleled levels of naturalism (known as verism) and commissioning massive projects for public works portraying intricate mythology and military conquests.

The Roman tradition of carrying portraits of deceased ancestors during religious processions fueled their taste for sculptural realism.

Beginning with Augustus, the first emperor, Roman rulers began to utilize sculptures as promotion; these sculptures, usually fashioned of bronze or marble, idealized their bodies and stressed (sometimes fictitious) links to famous military leaders of history.

Many Roman antiques and ancient Roman artifacts have since survived.

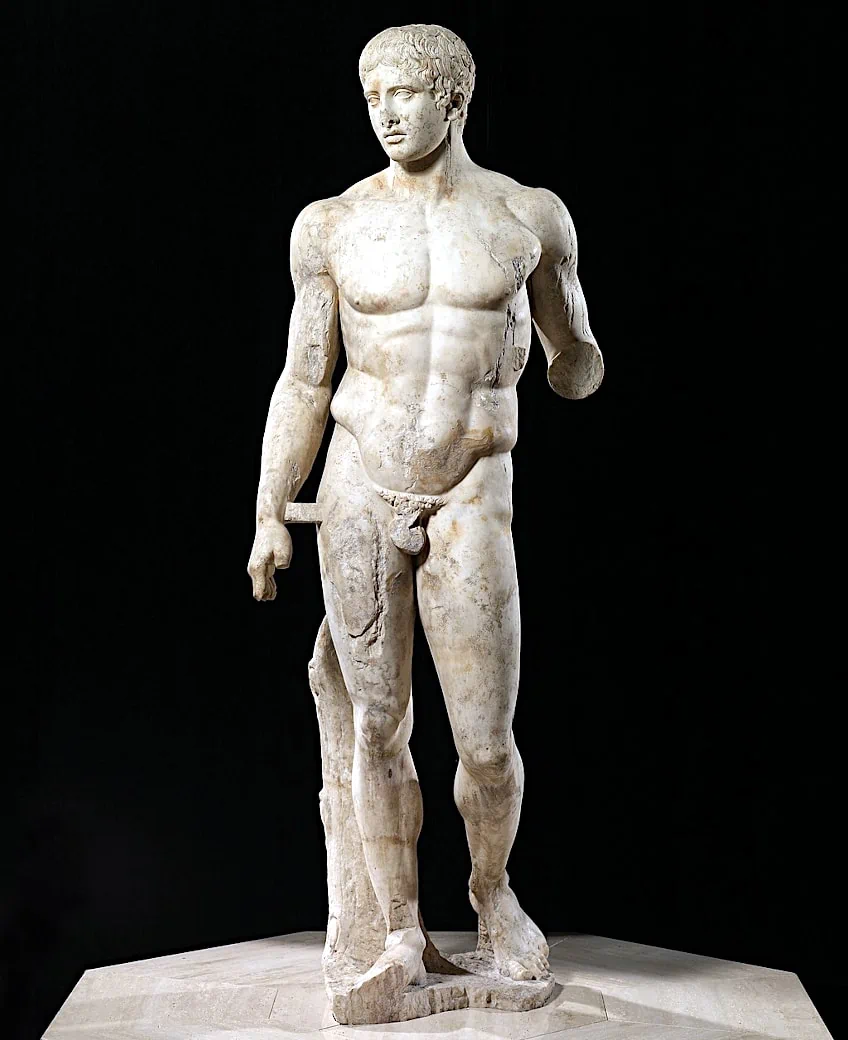

The Spear Bearer (440 BCE)

| Artist | Polykleitos (480 – 420 BCE) |

| Date | 440 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Location | Naples National Archeological Museum, Naples, Italy |

Roman Copy of the Doryphoros from 20 – 50 BCE, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman Copy of the Doryphoros from 20 – 50 BCE, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite the fact that this work of art is more evocative of ancient Greek culture and art, the Roman marble duplicate is remarkable. The Doryphoros of Polykleitos is a magnificent Greek statue portraying an athlete holding a lance in his hand with the tip positioned over his shoulder.

The oldest Roman marble reproductions found during excavations in Pompeii date from 120 to 50 BCE.

Rather than using bronze as the ancient Greeks had, the Romans produced their Doryphoros out of marble, which was much cheaper. This prompted the ancient Romans to include one or more such monuments in the gardens and homes of wealthier clientele. While there is no trace of the authentic statue, its prominence among Roman customers and rulers led to its popularity in art history.

The Orator (1st Century BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century BCE) |

| Date | c. 1st century BCE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Location | National Archaeological Museum, Florence |

Aulus Metellus, Stockstad, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Aulus Metellus, Stockstad, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This life-size bronze sculpture of Aulus Metellus (Aule Metele in Etruscan), comes from the early 1st century BCE and relates to the Roman Empire’s beginnings. The Orator extends his arm to the throng; despite being Etruscan, he is dressed like a Roman magistrate, wearing boots and a toga.

The Aulus Metellus sculpture was created as a votive offering, which is an object given to any panhellenic god in exchange for the fulfillment of a petition and could be anything from a homemade effigy to a commissioned sculpture if the donor of the tribute is affluent.

The statue’s status as a votive offering is debatable, however, with some historians claiming it was an honorary sculpture designed for public display rather than a gift to the gods. Honorary monuments served a social and political function in addition to being decorative in public places. There is some disagreement over the original owner’s family and their social standing.

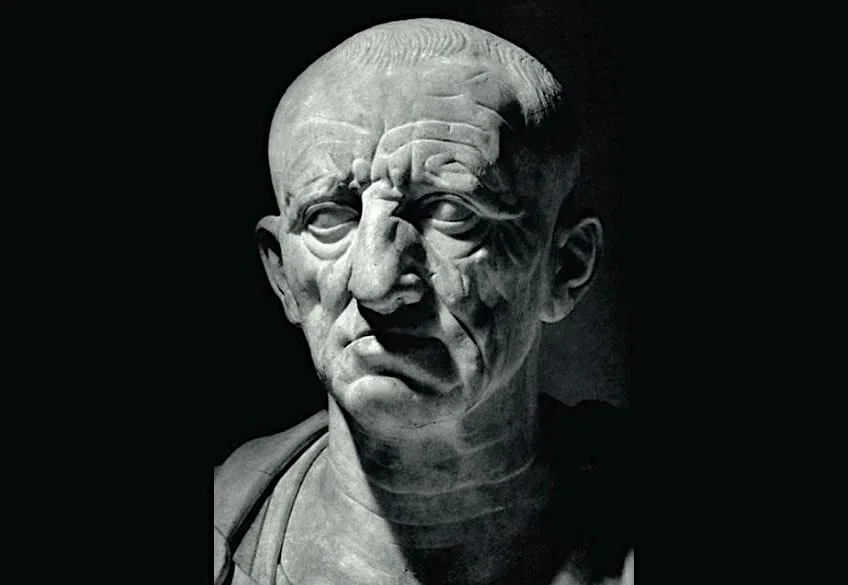

Head of a Roman Patrician (1st Century BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century BCE) |

| Date | c. 1st century BCE |

| Medium | marble |

| Location | Palazzo Torlonia, Rome |

Patrician Torlonia, Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Patrician Torlonia, Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The visage of a Roman aristocrat, aged and toothless, with drooping jowls, peers at us through the centuries. The physical characteristics of this portrait are supposed to show earnestness of thought and the nobility of a public vocation in the Late Roman Republic aesthetic lexicon by demonstrating how the individual visibly wears the signs of his efforts.

While this representational method may appear strange in the postmodern world, it was a successful means of competing in an ever more complicated socio-political arena in the closing days of the Roman Republic.

The portrait subject’s identity is no longer known, but it depicts a robust male nobleman with a pointy nose and prominent cheekbones. The figure is frontal, with no suggestion of movement or passion, which distinguishes the image from several of its contemporaries.

Prominent wrinkles, a furrowed forehead, and an overall image of drooping, sunken skin define the portrait head in the realist style of Roman portraiture.

Augustus from Prima Porta (1st Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century CE) |

| Date | c. 1st century CE |

| Medium | marble |

| Location | Musei Vatican, Rome |

Augustus of Prima Porta, Vatican Museums, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Augustus of Prima Porta, Vatican Museums, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Augustus ascended to power after putting a stop to a century of civil strife to emerge Rome’s first emperor. Augustus was a big fan of public art, and he exploited his acquisitions to validate his new position. He commissioned around 70 portrait sculptures of himself. They all point to an aristocratic ancestry dating back to Romulus, the father of Rome.

This full-body marble statue was discovered in the remnants of the Villa of Livia at Prima Porta and is now on exhibit at the Vatican.

It emphasizes Augustus’ military prowess and alludes to the Republic’s previous golden age, which he claimed to restore under his rule. Augustus’ breastplate displays a personal diplomatic achievement, exemplifying his ambitions: It depicts a Parthian ruler reintroducing military emblems taken from Roman armies.

Cupid appears by Augustus’ right ankle, reinforcing the emperor’s God-given right to reign.

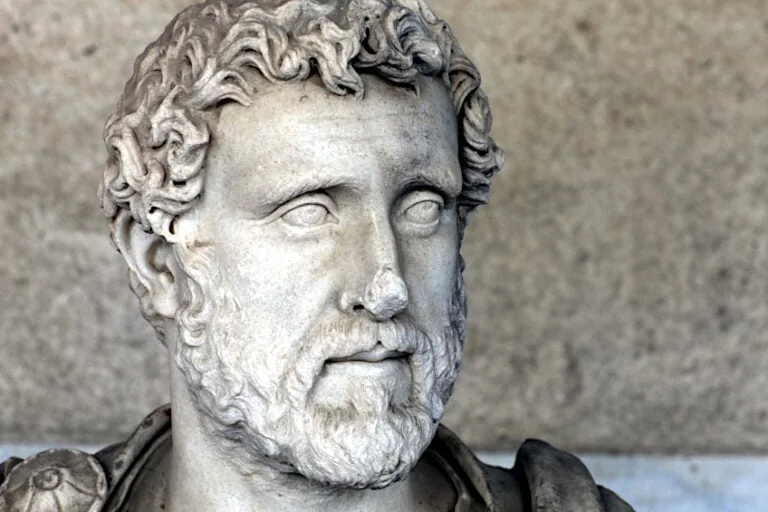

Fonseca Bust (2nd Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 2nd century CE) |

| Date | c. 2nd century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Location | Capitoline Museum, Rome |

Portraits of elite Roman women were significantly less realistic than those of their male counterparts since they were intended to emphasize female attractiveness and the latest styles rather than realistic depictions. The piled-on curls atop this woman’s head not only make her the most stylish inclusion on this list, but they also hint at the Romans’ love of ornate hairstyles.

Rich Roman ladies paid hairdressers to curl their tresses with irons or stitch in extensions.

This style would almost definitely have necessitated the use of extensions. This statue most likely represents a Flavian dynasty woman. Portraits of males from this era favored realistic depictions, although this one is exaggerated to highlight the sitter’s beauty.

Many busts from this period feature women with intricately curled, Marie Antoinette-style hair; artists were able to produce exquisite spirals thanks to new improvements in drilling and aesthetic skill.

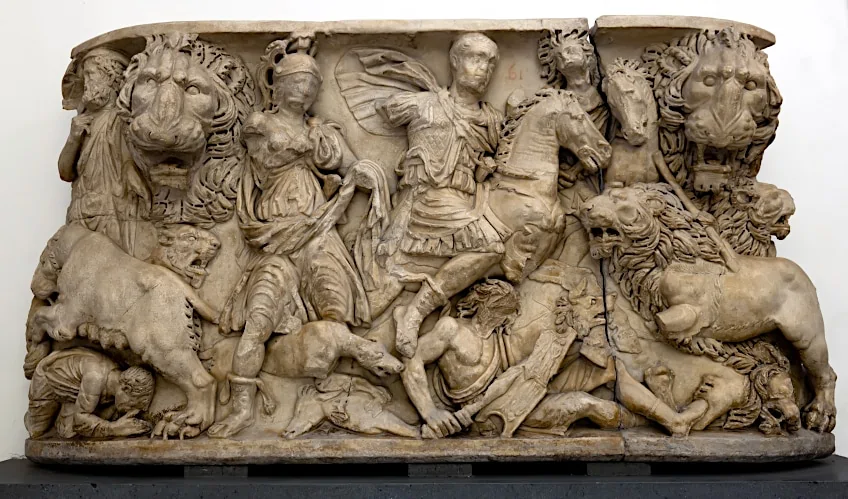

Trajan’s Column (110 CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 110 CE) |

| Date | 110 CE |

| Medium | Carrara marble |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

Trajan’s Column is one of the numerous public monuments commissioned by Emperor Trajan when he captured Dacia in 107 CE, a conquest that expanded the Roman Empire to its maximum size. The column, which also functioned as Trajan’s mausoleum, is over 100 feet in height and is ornamented with a curving frieze honoring the two victories against Dacia.

While archaeologists have utilized the column to better comprehend both Roman war strategy and the enigmatic Dacian society, the truth of its narrative is still debated.

The frieze has approximately 2,000 characters sculpted in shallow relief. Trajan’s men bring him with two decapitated enemy skulls in one scene. The column was a work of propaganda art. It was built shortly after the fight, in 110 AD, and it still exists in its original place, in Rome’s Forum of Trajan.

Although it was originally located between two libraries, the remainder of the forum has since been destroyed, leaving the column as the only relic of the emperor’s military power.

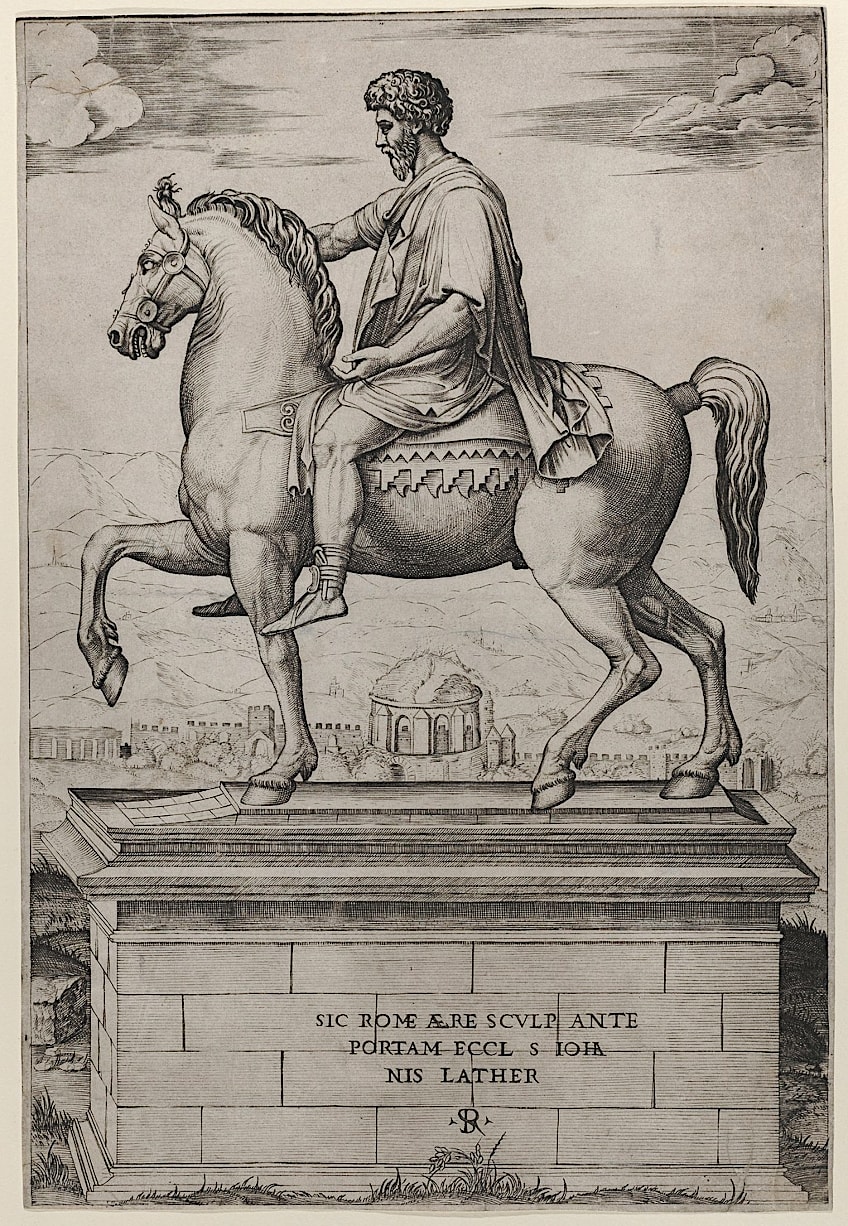

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (176 CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 176 CE) |

| Date | 176 CE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

Marcus Aurelius, Anonymous Unknown author Alvesgaspar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Marcus Aurelius, Anonymous Unknown author Alvesgaspar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A monument of Marcus Aurelius sitting atop his horse, most likely created around 176 AD, served as a template for most equestrian monuments throughout European art history. The ruler, who reigned from 161 to 180 AD, extends his right arm while his horse extends its right foreleg, displaying amazingly accurate musculature. Equestrian monuments were widespread in ancient Rome, honoring war and political achievements, but only a few have survived completely intact.

The Catholic church demolished many pagan monuments during the Middle Ages, but this one was kept because it was incorrectly thought to depict Constantine, the first Christian ruler of Rome.

Engraving of Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, Marco Dente, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Engraving of Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, Marco Dente, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

From roughly the 8th century, the monument stood in Rome’s Lateran Palace, a residence for aristocrats and then a papal home, until it was relocated in 1538 to the top of Capitoline Hill. Michelangelo restored it there, a fervent enthusiast of its realistic impression of motion.

The monument was moved to the Palazzo dei Conservatori for preservation in 1981, and a replica now resides in its original location on the piazza.

Column of Marcus Aurelius (193 CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 193 CE) |

| Date | 193 CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

The Column of Marcus Aurelius was constructed in recognition of the victorious military operations that Emperor Aurelius conducted against the Sarmatian and German tribes, and it was modeled after its significantly more well-known forerunner, the Column of Trajan. When you factor in its seven-meter underground base, it seems even more astounding. The independent campaigns of Marcus Aurelius against the Germanic and Sarmatian forces between 175 and 172 BCE are each depicted in a spiral on the surface of this seemingly straight Doric column’s relief sculptures, which are carved in 21 different spirals.

However, there are also some fascinating events where Marcus can be seen attempting to address his soldiers or where amazing Roman design feats are emphasized. The majority of these narratives depict events from the two major confrontations.

Arch of Septimius Severus – 203 CE

| Artist | Unknown (c. 203 CE) |

| Date | 203 CE |

| Medium | White marble |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

This arch was also built to commemorate the Roman Emperor’s victory, like all the others. It was a great accomplishment for the Romans that their military victories during the reign of Emperor Septimius led to the Roman empire’s expansion into Iran and modern-day Iraq.

This prestigious accomplishment led to the creation of the arch. It is a triumph made of white marble, with Proconnesian marble and travertine mixed inside.

The Four Tetrarchs – 300 CE

| Artist | Unknown (c. 300 CE) |

| Date | 300 CE |

| Medium | Porphyry |

| Location | Venice, Italy |

Many tourists to Venice miss the Four Tetrarchs, which are nestled away in a corner of Piazza San Marco. Nevertheless, the sculpture’s subject matter, form, and materials all hint at the late Roman Empire’s expanded structure. It is constructed of porphyry, a rare Egyptian rock with a distinctive reddish-purple color, and is intended to highlight imperial strength. The sculpture depicts the Tetrarchy, a government established by Emperor Diocletian to end decades of civil warfare and foreign invasions that had besieged Rome.

The empire had grown too enormous for any one man to manage, so he established the Tetrarchy, or “rule of four,” by dividing the empire in half and appointing a ruler and vice-emperor to each quarter.

The four similar-looking characters are arranged into pairs, with one hairy and one smooth-faced monarch in each half. Each of the four emperors wields his weapon in one hand, indicating strength and power, while the other hand hugs his fellow man, accentuating friendliness. These statues are most likely not intended to symbolize a specific monarch, but rather to suggest the authority of the office.

This approach of repressing individual individuality in favor of the communal departs from both Verism and Classicism and is more akin to the Early Christian approach.

Although Roman antiques were very influenced by the preceding Greeks, one can still identify elements that make them distinctly Roman. The Roman Empire was famous for its innovations, techniques, myths and legends, art, and statues. The ancient Roman artifacts created in this Empire throughout its era, like all other advancements and inventions, have tremendous value and influence on the world both then and now.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Did Leaping Dolphins Represent in Ancient Roman Artifacts?

Many Greek and Roman myths feature leaping dolphins. They are symbols of romance in this context, demonstrating the theme set in place by the portrayal of Venus. The appearance of these leaping dolphins along with Venus also serves as a symbol of the legend that Venus was brought into the world from the sea.

Where Can Roman Antiques Be Found Today?

Because the Roman Empire was so very large, they left behind many Roman antiques. These famous Roman artifacts can now be found in museums across the world. There are even thousands of ancient Roman artifacts in private collections. The best way to view them is to visit a museum though.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.