African Artifacts – Ancient Treasures From Continental Africa

All across the world, museums feature incredible examples of ancient African artifacts. These objects range from West African artifacts, such as the Benin Bronzes from Nigeria, to Zimbabwean artifacts, such as the Zimbabwe Birds. One can also find ancient African sculptures looted from ancient African royalty. The question being asked across the world currently is whether foreign museums should be allowed to keep stolen ancient African artifacts. As evidenced by the success of the Egyptian museum in Cairo, the ability display a broad selection of local antiquities can serve as a major drawcard for tourists and significantly boost a country’s economy and historical self-awareness. Below is a selection of artifacts from across Africa. Some are still in exile, others take pride of place in their countries of origin.

Contents

- 1 Fascinating Examples of Ancient African Artifacts

- 1.1 Tomb of Tutankhamun (c. 1325 BCE)

- 1.2 Golden Rhinoceros of Mapungubwe (c. 1250-1290 CE)

- 1.3 Nok Terracottas (c. 500 BCE-200 CE)

- 1.4 The Rosetta Stone (196 BCE)

- 1.5 The Lydenburg Heads (c. 500 CE)

- 1.6 The Zimbabwe Birds (11th – 14th Century)

- 1.7 Seated Figure (Djenné People) (13th Century)

- 1.8 Brass Head of Ife (14th – 15th Century)

- 1.9 Benin Bronzes (c. 16th – 17th century)

- 1.10 The Bangwa Queen (1899)

- 2 Frequently Asked Questions

Fascinating Examples of Ancient African Artifacts

This year, the West African artifacts known as the Benin Bronzes will finally be returned to Nigeria – a century after they were stolen following the colonization of Africa. The bronzes include ancient African sculptures, ornaments, and plaques which were originally created for the altars of ancient African royalty.

British troops stole thousands of these ancient African artifacts in the 19th century and auctioned them off to museums and private collectors across the world.

Tomb of Tutankhamun (c. 1325 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1325 BCE) |

| Date | c. 1325 BCE |

| Medium | Various artifacts |

| Site Found | East Valley of the Kings, Egypt |

| Current Location | East Valley of the Kings, Egypt |

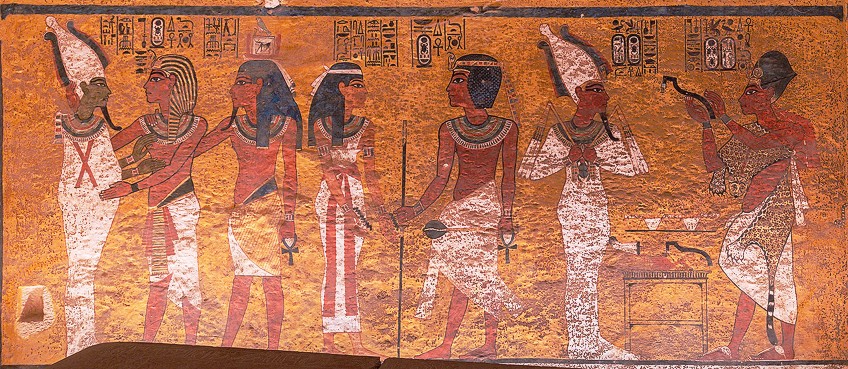

Scenes from the north wall of the burial chamber; Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Scenes from the north wall of the burial chamber; Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The tomb of King Tut, which dates back 3,300 years to Egypt’s New Kingdom, was found in 1922 by a crew of researchers led by British Egyptologist Howard Carter. It was the smallest royal tomb discovered in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, but it was the most well-preserved. The tomb revealed to the contemporary world the enormous richness that ancient pharaohs of Egypt carried with them to the grave, comprising a vast collection of thousands of ancient African artifacts, such as an iron knife forged from a meteorite and an intricate funerary mask.

Since the clearing effort started, the tomb has been a major tourist site. Someone broke inside the tomb after the mummy was reinterred in 1926, snatching artifacts Carter had left in place.

Golden Rhinoceros of Mapungubwe (c. 1250-1290 CE)

| Artist | Mapungubwe craftsmen (13th century) |

| Date | c. 1250-1290 CE |

| Medium | Gold |

| Site Found | Mapungubwe Hill, Kingdom of Mapungubwe, Limpopo |

| Current Location | Mapungubwe Collection, University of Pretoria Museums, Tshwane, South Africa |

Golden Rhinoceros of Mapungubwe (1075 – 1220 CE) from South Africa; Sian Tiley-Nel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Golden Rhinoceros of Mapungubwe (1075 – 1220 CE) from South Africa; Sian Tiley-Nel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Golden Rhino of Mapungubwe may be small enough to fit in your hand, but it nevertheless has profound meaning over 800 years after it was lost to time. It represents one of the area’s most imposing creatures, the rhinoceros, as well as one of the area’s most lasting emblems of power, gold. The rhino was discovered in 1934 in a monarch’s cemetery at Mapungubwe in northern South Africa, near the border with Zimbabwe. Its development in the 13th century reflects the opulence of Mapungubwe, southern Africa’s first recorded monarchy. Throughout the 13th century, gold became the most significant commercial export. As a sign of aristocratic power and wealth, it eventually superseded glass beads.

The golden rhino was buried alongside a member of Mapungubwe’s reigning royal class, adding to its symbolic potency.

Nok Terracottas (c. 500 BCE-200 CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 500 BCE-200 CE) |

| Date | c. 500 BCE-200 CE |

| Medium | Terracotta |

| Site Found | Nok, Nigeria |

| Current Location | Metropolitan Museum, New York |

Nok sculpture, terracotta; Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nok sculpture, terracotta; Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tin miners in the town of Nok near the Jos Plateau area of Nigeria in 1943 uncovered a clay head, proof of the earliest documented figurative art south of the Sahara. Despite the fact that visually comparable heads, animals, figures, and pottery fragments have been unearthed at a multitude of Nigerian sites since then, such pieces are designated by the name of the little community where the first clay head was unearthed. Ancient African artifacts are still being discovered without a record of their burial setting, owing to a lack of substantial archaeological inquiry that has drastically curtailed our understanding of Nok Terracottas.

The Nok civilization, one of the earliest African hubs of terracotta figure manufacturing and ironworking, remains a mystery.

The Rosetta Stone (196 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 200 BCE) |

| Date | 196 BCE |

| Medium | Granodiorite |

| Site Found | Rashid, Rosetta, Egypt |

| Location | The British Museum, United Kingdom |

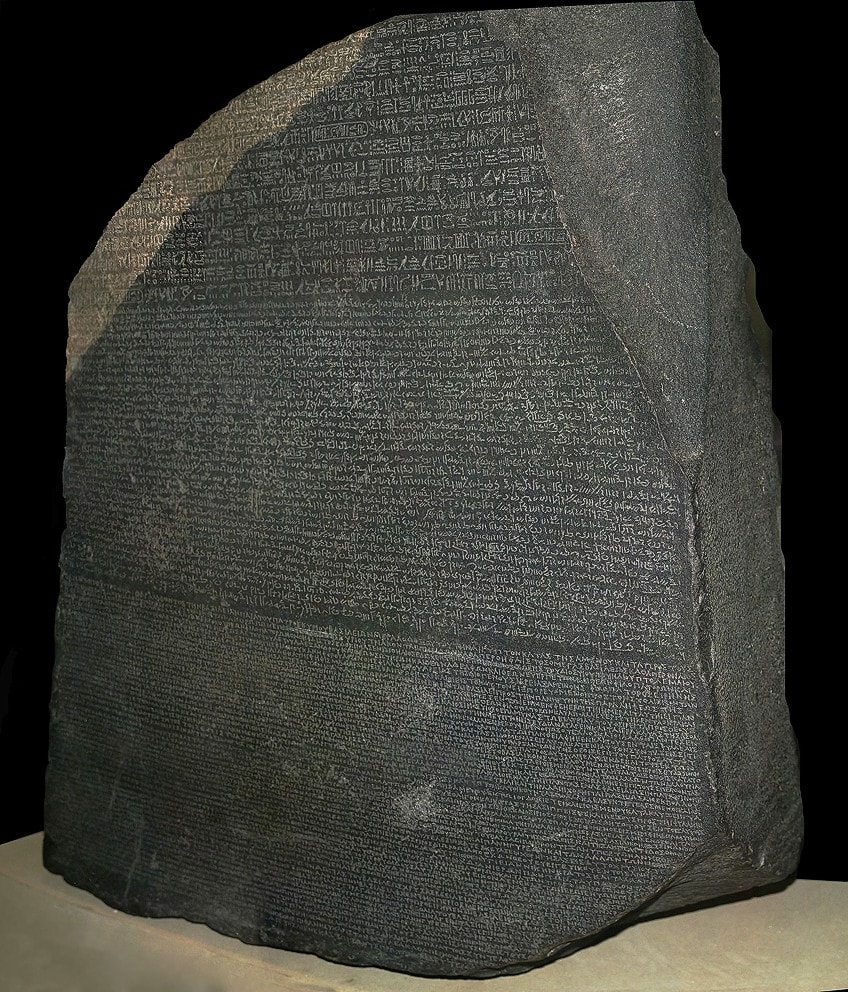

Rosetta Stone (196 BCE) from Egypt; © Hans Hillewaert

Rosetta Stone (196 BCE) from Egypt; © Hans Hillewaert

The stone is a fragmented piece of a larger stone slab. It contains a message etched in three different languages. It was a crucial revelation that enabled specialists in learning how to interpret Egyptian hieroglyphs. The inscription on the stone is an official edict about King Ptolemy V. The decree was engraved on enormous stone slabs known as stelae, which were placed in every shrine in Egypt.

The decree states that the priests of a Memphis temple endorsed the monarch. The Rosetta Stone is one of these reproductions, therefore it isn’t extremely significant in and of itself.

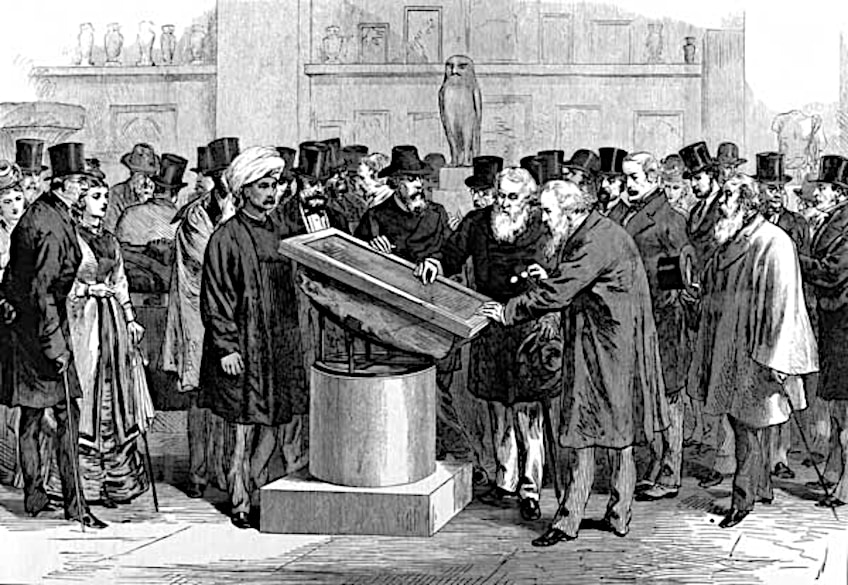

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the Second International Congress of Orientalists, 1874; British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the Second International Congress of Orientalists, 1874; British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The fact that the edict is written in hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Ancient Greek is significant to us.

The significance of this to Egyptology is enormous. Nobody understood how to interpret ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs when it was uncovered. The stone became a vital instrument for decoding the hieroglyphs since the inscriptions state the very same thing in three distinct languages and researchers could still decipher Ancient Greek.

The Lydenburg Heads (c. 500 CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 500 CE) |

| Date | c. 500 CE |

| Medium | terracotta |

| Site Found | Lydenburg, Mpumalanga, South Africa |

| Current Location | Iziko South African Museum, Cape Town |

Lydenburg Heads (Around 500 CE) from South Africa; Nkansahrexford, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Lydenburg Heads (Around 500 CE) from South Africa; Nkansahrexford, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This set of seven fired ceramic heads are named for the location where they were unearthed in South Africa’s eastern Transvaal (now Mpumalanga). These heads were buried there in approximately 500 CE., according to radiocarbon testing of charcoal fragments from the excavation site, rendering them the world’s oldest documented African Iron Age artworks.

The rebuilt heads are not exactly alike, but they do share some features.

Clay strips create the slightly parted oval eyes, somewhat protruding lips, ears, and noses, and raised bands that decorate the faces, while carved linear patterns decorate the back of the sculptures. Large wrinkled rings characterize the columnar necks. Many African cultures have historically regarded fat-ringed necks as a symbol of wealth. However, due to the scarcity of evidence about the ancient society that made them, it is currently difficult to establish whether the rings were intended to be interpreted in this manner.

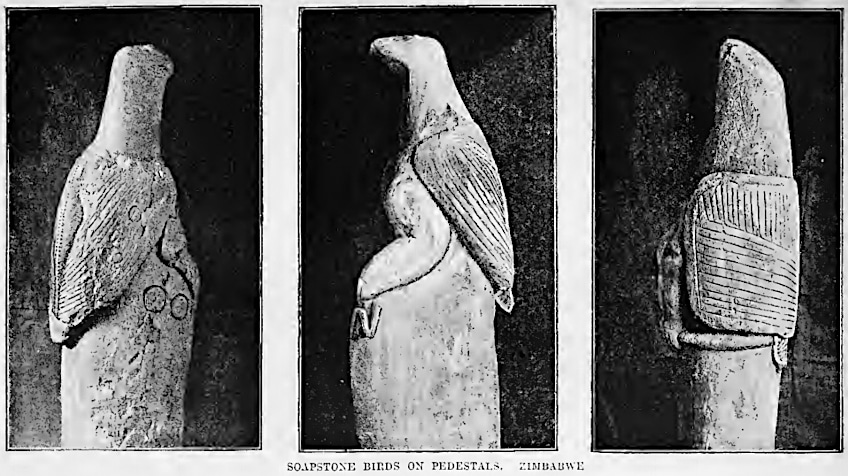

The Zimbabwe Birds (11th – 14th Century)

| Artist | Zimbabwean Craftsmen (11th – 14th century) |

| Date | 11th – 14th century |

| Medium | stone |

| Site Found | Various sites across Zimbabwe |

| Current Location | Various museums across Europe |

Zimbabwe Birds Sculptures (12 – 15th Centuries CE) from Zimbabwe; James Theodore Bent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Zimbabwe Birds Sculptures (12 – 15th Centuries CE) from Zimbabwe; James Theodore Bent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Willi Posselt, a European hunter, visited Great Zimbabwe in 1889 after learning about it from Karl Mauch, a fellow European explorer. Although he had been advised that it was a sacred location where he should not enter, he ascended to the highest altitude of the remains of a village and discovered the Zimbabwe Birds, significant Zimbabwe artifacts, in the center of an enclosure surrounding an altar.

The local tribesman who had taken him there was paid by Posselt with blankets and a few other items.

He chopped the bird off its perch and concealed the pedestal with the aim of coming later to recover it because it was too large for him to move. He later sold the sculpture to Cecil Rhodes, who had it displayed in the conservatory of his Cape Town home.

Seated Figure (Djenné People) (13th Century)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 13th century) |

| Date | 13th century |

| Medium | Terracotta |

| Site Found | Jenne-Jeno, Mali |

| Current Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Seated Figure (14th Century CE) from Mali; Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Seated Figure (14th Century CE) from Mali; Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This eerie figure is huddled down, its leg hugging its breast and its head resting on its knee. It evokes the coiled strain of worry as well as the majestic absorption of profound prayer. This exquisite piece, created over 700 years ago in the region of modern Mali, blurs the borders of place and time. This clay sculpture was discovered in Jenne-Jeno, Sub-Saharan Africa’s earliest known city. Jenne-Jeno thrived in the ninth century but fell out of favor around 1400. Items made of forged iron and cast brass, as well as clay containers and figurines like this one, have survived.

These compelling objects bear witness to what experts believe was a diverse and sophisticated urban life.

A few carefully regulated archaeological investigations reveal only vague ideas of the historical value of this period and the region’s art. Terracotta figurines that have been recovered are typically highly detailed. Clothing, jewelry, and body ornamentation, such as the consecutive columns of ridges and circles on the back of this sculpture, are common features. Occasionally, they completely cover the body and appear to be pustules from some kind of terrible disease.

Brass Head of Ife (14th – 15th Century)

| Artist | Nigerian craftsmen (14th – 15th century) |

| Date | 14th – 15th century |

| Medium | Brass |

| Site Found | Ife, Nigeria |

| Current Location | British Museum, London |

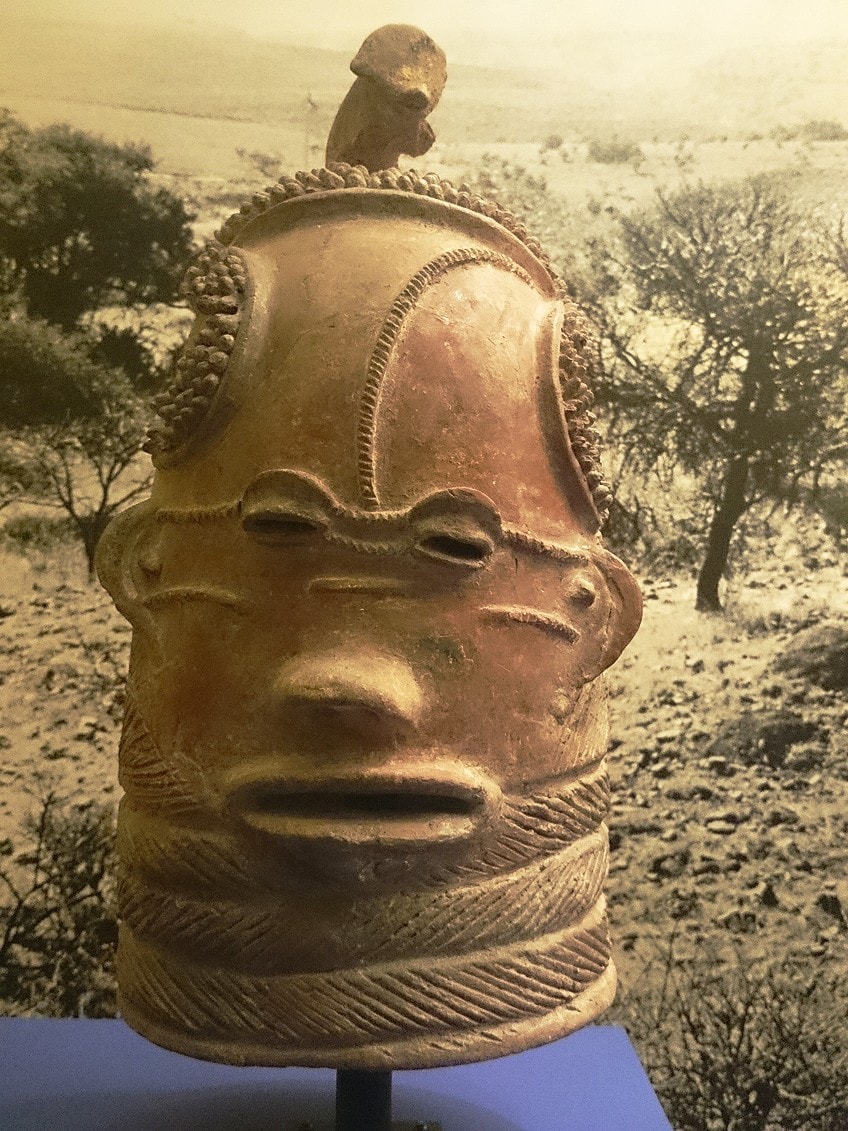

Bronze Head from Ifẹ̀ (14 – 15th Centuries CE) from Nigeria; I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bronze Head from Ifẹ̀ (14 – 15th Centuries CE) from Nigeria; I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Brass Head from Ife, discovered in 1938 in Ife, Nigeria, is one of 18 copper alloy artworks that defied Western perceptions of African art. The elaborate and lifelike characteristics of the head, created around the 14th or 15th century, demonstrated a level of skill that is so unusual in African art that scholars throughout the world were shocked.

This amazing piece of brass casting is believed to portray a ruler of the West African kingdom of Ife, is regarded as one of the pinnacles of African culture and art.

The head was created in a highly lifelike way by the artist. The face has incised markings, but the lips are untouched. The headgear resembles an intricate crown made of multiple layers of tassels and beads. This ornamentation is characteristic of the bronze heads produced in this particular region.

Benin Bronzes (c. 16th – 17th century)

| Artist | Benin craftsmen (c. 16th – 17th century) |

| Date | c. 16th – 17th century |

| Medium | Bronze and brass |

| Site Found | Benin City, Nigeria |

| Current Location | British Museum, United Kingdom |

Benin Bronzes (From the 13th Century CE) from Nigeria; English-speaking Wikipedia user Warofdreams, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Benin Bronzes (From the 13th Century CE) from Nigeria; English-speaking Wikipedia user Warofdreams, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Benin Bronzes are a collection of ancient African sculptures that includes intricately adorned cast plaques, memorial heads, human and animal figures, regalia of ancient African royalty, and personal decorations. They were produced in Benin, beginning in the 16th century, by specialized guilds functioning for the royal palace of the king.

The Kingdom also funded guilds that worked in other materials like leather, ivory, coral, and wood, and the phrase Benin Bronzes is often used to refer to ancient African artifacts made from these other materials.

Many artworks were exclusively commissioned for the ancestral shrines of previous kings and Queen Mothers. They were also employed in various rites to honor ancestors and legitimize the appointment of a new ruler. The brass plaques that originally adorned the Benin royal court and provide a significant historical archive of the Kingdom are some of the most renowned of the Benin Bronzes.

The Bangwa Queen (1899)

| Artist | Bangwa Tribe (c. 1890s) |

| Date | Stolen in 1899 |

| Medium | Wood |

| Site Found | Fontem, Cameroon |

| Current Location | Dapper Foundation, France |

In addition to being one of the most recognized works of African art in the world, the Bangwa Queen also has significant religious importance in Cameroon. The female wooden sculpture is a physical representation of the Bangwa people’s health and strength, a tribe who are indigenous to western Cameroon. It was seized by German colonists in 1899 and auctioned off for $3.4 million. It is presently under the possession of the Dapper Foundation in Paris.

The recovery of artifacts lost due to colonial powers is a contentious topic.

One typical answer is that “it was lawful at the time” and hence not a legal concern. However, is that still valid in the contemporary era? Instead of relying just on property ownership, a human rights legal approach that focuses on the heritage of cultural artifacts and how it affects the people of those cultures today can perhaps provide the necessary answers to resolve this issue.

Many of the most magnificent examples of ancient African artifacts belonged to ancient African royalty and the people they served. These ancient African sculptures and other artifacts display a level of craftsmanship that was not thought possible by the Europeans who eventually discovered them. However, upon their discovery, thousands of these African artifacts were sold to European collectors, and thus, much of the great art of Africa has been taken out of the land where they were created.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Are the Most Ancient African Artifacts Housed?

During the era of colonization, most of the African artifacts that were discovered were taken back to Europe. There they were displayed in museums and private collections with little regard for the original land or tribe from which they came. Some of those objects were later sold to north American museums and institutes of higher learning. Following years of lobbying by African countries, many institutions with stolen objects in their collections are now facing increasing pressure to return these ancestral treasures.

Is the Looting of Artifacts Legal?

There were extended periods in human history when it was not illegal to loot another country’s artifacts. In antiquity, invading armies would not just take trophies home as proof of conquest, but looting was often the very purpose of the invasion. In later periods, items of cultural or material value would be taken under the guise of “scientific interest” to be studied by scholars or displayed by monarchs and elites as proof of their intellectual pursuits. More recently, such as with the case of the removal of sections of the Parthenon frieze from Greece by Lord Elgin, artworks were taken under the rationale that this would protect them from destruction. Many of the world’s largest and most prestigious museums still have items that were obtained without the consent of their original owners. Some museums are taking steps to return these artifacts to their places of origin.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.