Mesopotamian Art and Architecture – The Cradle of Civilization

Mesopotamian art and architecture originated in the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, home to the Sumerian, Assyrian, and Babylonian civilizations. This region would become incredibly important as a cradle of human urban development, and the many Mesopotamian artifacts and buildings would go on to influence many cultures that followed. So, read on to learn a lot more about this ancient region and what its civilizations created.

A Look at Mesopotamian Art and Architecture

The cultures that flourished in the region of Mesopotamia produced an extensive array of artistic and architectural marvels. The region was located in the Near East, and it could be found between and around the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers. The first of the Mesopotamian civilizations originated in about 3100 BCE and the last only ended by 539 BCE.

Map of Ancient Mesopotamia; Goran tek-en, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Map of Ancient Mesopotamia; Goran tek-en, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What we know about Mesopotamia is derived from the available evidence, the textual clues left on clay tablets and structures, and pictorial and sculptural representations that adorn buildings, and a range of everyday artifacts such as vessels, seals, and jewelry that have been excavated across the region.

What Is Mesopotamian Art?

Mesopotamian art includes a large variety of different types. There are statues, steles, reliefs, mosaics, and sculptures. We know that the Mesopotamian cultures developed philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, medicine, complex administrative systems for keeping records, and advances in the creation of materials such as glassware, bronze, and woven wool. Ancient Mesopotamia is also believed to have seen the first use of the potter’s wheel. Of real importance however, was that they invented beer!

Mesopotamian art ranged from megalithic structures to jewelry and finely detailed seals designed to imprint images into clay or wax. Impressive statues and reliefs also adorned important structures like palaces or temples. Most of what remains today are the ruins of massive temple complexes built around towering structures known as ziggurats.

Relief depicting archers with spears from the Ishtar Gate (c. 575 BCE); O.Mustafin, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Relief depicting archers with spears from the Ishtar Gate (c. 575 BCE); O.Mustafin, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mesopotamian artisans made use of a variety of materials, such as colored limestone, gold and silver, bronze, and shells. It may have been an ancient culture, but it had experimented with its artforms and was able to produce items of far higher sophistication than anything else around.

Some Examples of Mesopotamian Art and Artifacts

The art of Mesopotamia is the art of an ancient civilization. This means that, by today’s standards, many of these pieces of art have become far better known as historical artifacts than simple pieces of art. The distinction between Mesopotamian art and Mesopotamian artifacts is not a simple one to make as art inevitably eventually becomes an artifact with time. However, the list below is a few Mesopotamian artifacts and even those that may not have been created as art can be viewed as part of the artistic tradition of the region. So, below we will consider a few of these Mesopotamian artifacts.

The Urfa Man (Around 9000 BCE)

| Created | Around 9000 BCE |

| Materials Used | Sandstone |

| Function | Statue |

| Discovery Location | Balıklıgöl, Turkey |

The Urfa Man is a human-shaped statue, also known as the Balıklıgöl statue because of where it was discovered. It was found during excavations in this location and its discovery was a revolutionary one. This ancient piece of Mesopotamian art was dated to be around 9000 BCE, and this makes it part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period. It is also considered to be the oldest currently discovered life-sized depiction of a naturalistic human.

The Urfa Man (c. 9000 BCE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Urfa Man (c. 9000 BCE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This truly ancient piece of the art of Mesopotamia is nearly 1.9 m tall, it has hollowed-out eyeholes, and a V-shaped collar/necklace, it has its hands in front of itself, and its eyes was made of black obsidian. There have been various other discoveries of naturalistic human figures that are much older, but the difference is that those were statuettes and so they were significantly smaller in design.

The Urfa Man was discovered during construction work and the exact location was not actually recorded, but it was supposedly found in 1993. However, despite the lack of record-keeping for the early days of its rediscovery, it has become one of the most important pieces of ancient Mesopotamian art yet found.

The Code of Hammurabi (1792 – 1750 BC)

| Created | 1792 – 1750 BC |

| Materials Used | Basalt |

| Function | Legal text |

| Discovery Location | Susa, Iran |

The Code of Hammurabi is an ancient legal text that has been inscribed onto a large stele made of basalt. The full stele is 2.25 m (or 7.4 ft) tall. This particular legal code is the best preserved and organized text of its kind that has been found in the ancient Near East. It was written in Akkadian, an Old Babylonian dialect, and, as the name suggests, it was supposedly written by Hammurabi of the First Dynasty of Babylon.

Copy of The Code of Hammurabi in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, (1792 – 1750 BCE); GualdimG, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Copy of The Code of Hammurabi in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, (1792 – 1750 BCE); GualdimG, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This ancient legal text discusses many different aspects of the law and explores the offenses associated with those areas, such as laws focused on property, commerce, marriage, assault, and many others. There is some uncertainty among scholars about the definiteness of its place as a long-standing legal code in genuine use, but it has become an important Mesopotamian artifact outside of academic circles and is seen as a piece of legal history that now stands as a symbol for the law. This is also why there are many replicas of it in various locations, such as the United Nations.

In addition, this legal code is an example of the Ancient Mesopotamian arts as it includes a relief of Hammurabi with the Babylonian god of the sun and justice, Shamash. The code is located directly below it and there are about 4,130 lines of cuneiform text for the prospective reader to peruse and learn from. It may be a legal document, but it is also representative of the art of Mesopotamia.

Thanks to its place as a legal text and a piece of Mesopotamia art, the Code of Hammurabi is one of the greatest Mesopotamian artifacts to have been discovered, and it was discovered in 1901 in present-day Iran in the Susa archaeological site. It was actually there because it had been taken there over six hundred years after its creation and it was extensively studied by Mesopotamian scribes, but today it has a new home. It sits, for all to see, in the Louvre Museum.

The White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I (1050 – 1031 BCE)

| Created | 1050 – 1031 BCE |

| Materials Used | Limestone |

| Function | Commemoration sculpture |

| Discovery Location | Nineveh, Iraq |

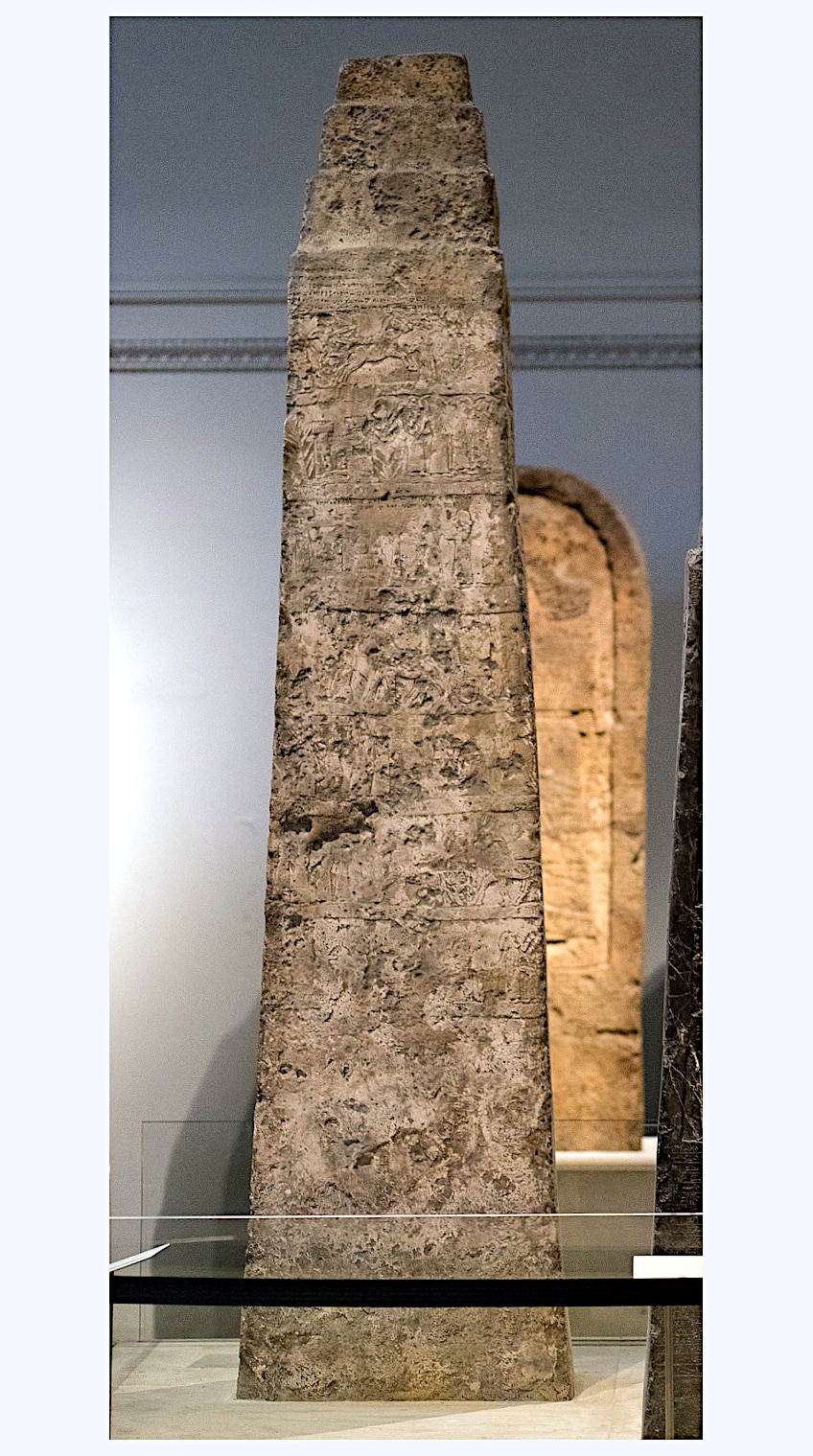

The White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I is an ancient piece of Mesopotamia art that is in the form of a large limestone monolith. It is one of only two such Assyrian obelisks, the other is the much younger Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III. This obelisk dates back to the reign of the man after whom it is named, Ashurnasirpal I. The obelisk features several images depicting a range of activities including military campaigns and a hunt orchestrated by the king.

One of the reasons that it is believed to have been created during the reign of Ashurnasirpal I is because of the fashion depicted in the obelisk’s artworks. There are characters wearing Fez-like hats that were common during his reign, making this one of the oldest pieces of Assyrian art ever discovered.

The White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I (1050 – 1031 BCE); Paul Hudson from United Kingdom, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I (1050 – 1031 BCE); Paul Hudson from United Kingdom, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The obelisk itself also contains more art of Mesopotamia. It includes engravings that show some of the expeditions that were made by the king, a few great banquets that would have been enjoyed by the monarchs, and depictions of tributes that the king would have received during his time among the people. There is even one engraving that depicts the king pouring out a libation before Ishtar, the goddess of love and sexuality, who was also the main deity in the city. In addition, that religious image has an inscription to explain what’s happening.

There are many pieces of inscription acroos the obelisk, and they explain some of what is depicted, such as how great a conqueror the king was, how much loot he took from the places he conquered, and the various prisoners and animals that were taken under his command. It is a grand commemoration of a king whose exploits would have otherwise been lost to time for eternity.

The White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I was ultimately excavated by a British archaeologist named Hormuzd Rassam back in 1853. This means that this particular obelisk is another of the many Mesopotamian artifacts that can be found in the British Museum to this day.

The Human-Headed Winged Bull (9th – 7th Centuries BCE)

| Created | 9th – 7th Centuries BCE |

| Materials Used | Gypsum |

| Function | Sculpture |

| Discovery Location | Northern Iraq |

The Human-headed Winged Bull, which is also known as a lamassu, is an ancient Assyrian sculpture that was originally designed to protect the throne room of the King of Assyria, Sargon II. This lamassu is a representation of a mythological hybrid creature that was made to be a combination of various animals. It had a human head, a bull body, and the wings of a bird. These creatures are also depicted in the ancient text, the Epic of Gilgamesh, and they were meant to serve as protective beings that could turn evil people away.

The Human-Headed Winged Bull (9th – 7th Century BCE); Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Human-Headed Winged Bull (9th – 7th Century BCE); Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The lamassu has five legs, and this was quite common for those created during this era, and the idea was that it could be seen as having four legs whether viewed from the front or the side. This also allows it to look as if it is walking or standing, and so it is a superb example of the Ancient Mesopotamian arts of sculpture and design. It also stands at 5 m (or 16 ft) and weighs about 40 tons.

These ancient sculptures were built under the orders of the Assyrian kings who ruled over the massive empires that are now in northern Iraq. There were many of them posted in locations that required some level of protection, such as the gates to cities and, in the case of the most famous one, it guarded the throne room of the king.

This particularly large version of a lamassu was rediscovered in Northern Iraq and was then moved to the Oriental Institute Museum, which is operated by the University of Chicago. It had to be disassembled when first found and then reassembled in its later resting place with a specially reinforced floor so that it wouldn’t damage anything. This ancient piece of Mesopotamia art can now be visited by anyone who happens to be in the area because as the entire building was constructed around this ancient sculpture, it physically cannot be moved without tearing the building down.

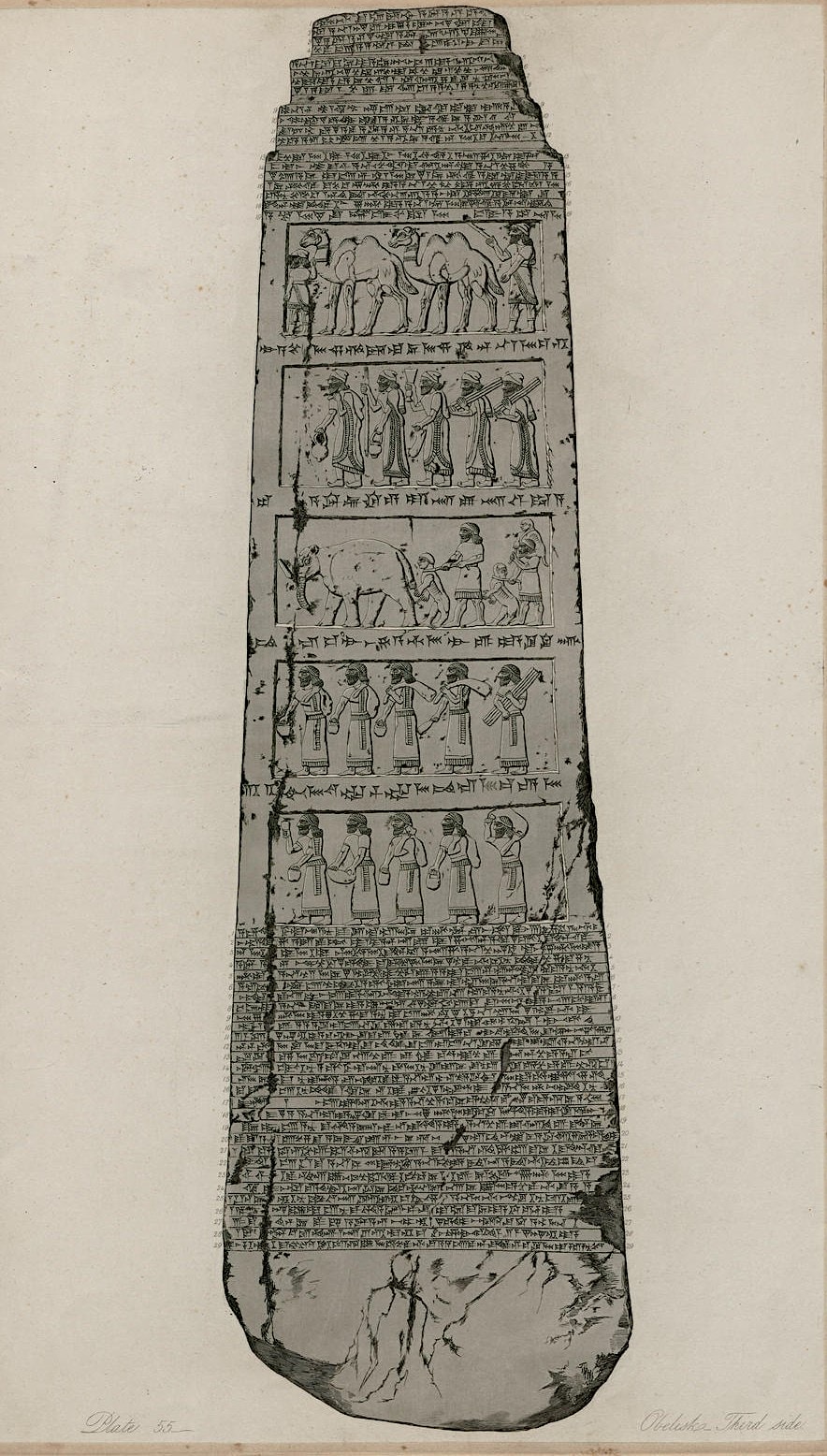

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (827 – 824 BCE)

| Created | 827 – 824 BCE |

| Materials Used | Black limestone |

| Function | Commemoration sculpture |

| Discovery Location | Nimrud, Iraq |

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III is a large Assyrian sculpture made of black limestone that features a variety of bas-reliefs and inscriptions around its base. The obelisk was discovered in Nimrud, in ancient times known as Kalhu, and it is a commemorative piece for the king at the time. The king in question is the one after whom it is named, Shalmaneser III.

This is one of only two such Assyrian obelisks that have been discovered, although the other one is much older, the White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I. The black obelisk is considered to be immensely important as a piece of world history, because some scholars have argued that it may to be the oldest depiction of a person mentioned in the Bible.

Drawing of The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III made by archaeologist Austen Henry Layard upon discovery in 1849 (827 – 824 BCE); Austen Henry Layard 1817-1894, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Drawing of The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III made by archaeologist Austen Henry Layard upon discovery in 1849 (827 – 824 BCE); Austen Henry Layard 1817-1894, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The possible biblical figure in question is Jehu, an ancient King of Israel. There have been debates about whether or not that is what the obelisk depicts, but it has been widely passed around as truth. There may be issues with this interpretation as there are transliteration and chronology problems that undermine this particular interpretation. Either way, the obelisk stands as an important piece of Mesopotamia art.

The obelisk, aside from the disputed imagery of a biblical character, also depicts images of five different kings that had been defeated. Each of those depictions is of rulers from specific locations even when the rulers themselves are not necessarily known. For instance, there are images of Marduk-apil-usur of Suhi and an unnamed ruler from Musri.

This Mesopotamian artifact was discovered in 1846 by Sir Austen Henry Layard and it was eventually moved to the British Museum like so many other pieces of ancient history. The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III stands, to this day, as a remarkable piece of the art of Mesopotamia.

What Is Mesopotamian Architecture?

Mesopotamian architecture was typically brick-oriented in nature. However, there was a focus on the use of rounded mud-bricks, which are not as stable as rectangular bricks. This did allow for some irregular creations though. These bricks were typically sunbaked, and this has led to the deterioration of Mesopotamian structures because oven-baked bricks are far stronger and resistant to the aging process. However, regardless of this, Mesopotamian architecture has a long and influential history. Many innovations came from this civilization, such as the improved construction of monumental structures like the ziggurats, regular urban planning, palace and temple construction, and even the construction of regular homes.

Mesopotamian architecture was ahead of its time, and that is plain to see in the fact that some of the greatest Mesopotamian buildings still exist to this day in some shape or form.

Some Examples of Mesopotamian Architecture

We will examine some of the most famous pieces of Mesopotamian architecture below. This form had many variations throughout the different civilizations within Mesopotamia, and they will be examined below. However, while there may have been differences, there were also many similarities. Keep reading to learn more.

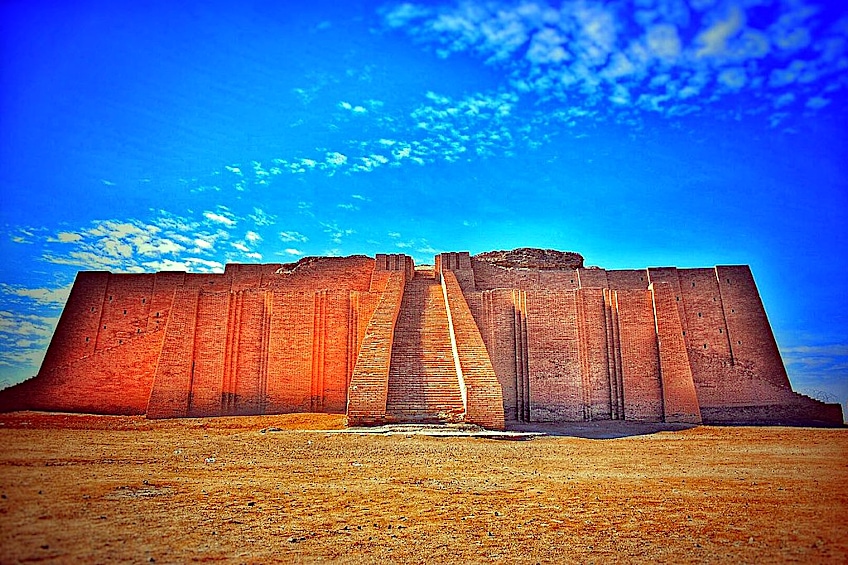

The Great Ziggurat of Ur (21st – 20th Century BCE) in Dhi Qar Province

| Monarch | Ur-Nammu (Before 2048 – 2030 BCE) |

| Date Constructed | 21st Century BCE |

| Function | Temple and administrative center |

| Location | Dhi Qar Province, Iraq |

The Great Ziggurat of Ur is a piece of ancient Mesopotamian architecture. It is a gigantic ziggurat located in what used to be the city of Ur, which is in the present-day Iraq province of Dhi Qar. It was built in the Early Bronze Age and had essentially fallen apart by the 6th century BCE, but then it was restored once again, and that version then fell to ruin too. This is a structure so ancient that the reconstruction of it is old enough to have become a ruin.

The ziggurat was built during the Third Dynasty of Ur, and it was specifically built under King Ur-Nammu. It was dedicated to the Mesopotamian god Nanna/Sîn. It does not exist in its original state any longer, but it would have once stood at a height of about 64 m (or 210 ft), but this height is speculative.

The Great Ziggurat of Ur (21st – 20th Century BCE); Amjedha95, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Great Ziggurat of Ur (21st – 20th Century BCE); Amjedha95, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

There are only parts of the original and the first reconstruction still standing. Those portions of the structure only comprise the lowest two levels, and the temple that would have been at the very top is no longer there at all. However, regardless of that, this structure is still one of the best-preserved ziggurats in Mesopotamia.

It once served a combination of duties. It was a temple to the moon god that served as the patron deity of the city, but it was also the administrative center of that city. The ziggurat is large and can be seen for miles in every direction, so it would have served as a good, landmarked destination for the people to congregate.

In recent years, it has not fared as well. In the 1980s, Saddam Hussein ordered a partial reconstruction. This meant a reconstruction of the lower façade and a newly created staircase in the style of the long-lost original. However, the site sustained explosive damage and the structure itself suffered small fire damage during the Gulf War. Mesopotamia buildings are hardy things though, and it has managed to mostly survive the damage.

The Dur-Kurigalzu Ziggurat (14th century BCE) in the Baghdad Governorate

| Monarch | Kurigalzu I (Unknown – 1375 BCE) |

| Date Constructed | 14th century BC |

| Function | Temple and administrative center |

| Location | Baghdad Governorate, Iraq |

Dur-Kurigalzu was a city that lay between the Tigris and Diyala rivers and wass located only 30 km from Baghdad. The initial site was founded by a Babylonian king named Kurigalzu I However, the entire site was later abandoned. It emptied after the demise of the Kassite dynasty in 1155 BCE. The city is the location of the Dur-Kurigalzu ziggurat, an ancient work of Babylonian architecture that still stands to this day.

The Dur-Kurigalzu Ziggurat (14th century BCE); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Dur-Kurigalzu Ziggurat (14th century BCE); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Dur-Kurigalzu ziggurat lies within this city, and it once stood at a height of 52 m (or 171 ft) but is currently in an utterly ruined state. However, it did serve as an important and very visible landmark in the region for centuries. In addition, because of its close proximity to Baghdad, it was a good way for caravans and foot traffic, in general, to head in that direction.

A funny piece of information about this famous example of Babylonian architecture is that many Western foreigners who visited the area from the 17th century onwards believed it to be the site of the Biblical Tower of Babel. Although, this may not be entirely ignorant as the Tower of Babel may have been inspired by the ziggurats of Mesopotamia.

The initial Mesopotamian building was constructed by Kurigalzu I and it was dedicated to the primary Babylonian god Enlil, who was the god of the wind, earth, storm, and air. So, this ziggurat was constructed using baked bricks that bore the name of the reigning monarch, and there was once a total of three grand staircases that led up to the first level where a terraced compound once resided. An axial staircase was discovered that once rose to the very top of the ziggurat where the temple was located.

However, all of these more specific details are now lost as the structure has not managed to withstand the test of time. Thousands of years of neglect left the building little more than a large column resembling rock. Even the greatest of buildings, whether they be Mesopotamia buildings or buildings of any other variety, will not last forever when left unattended.

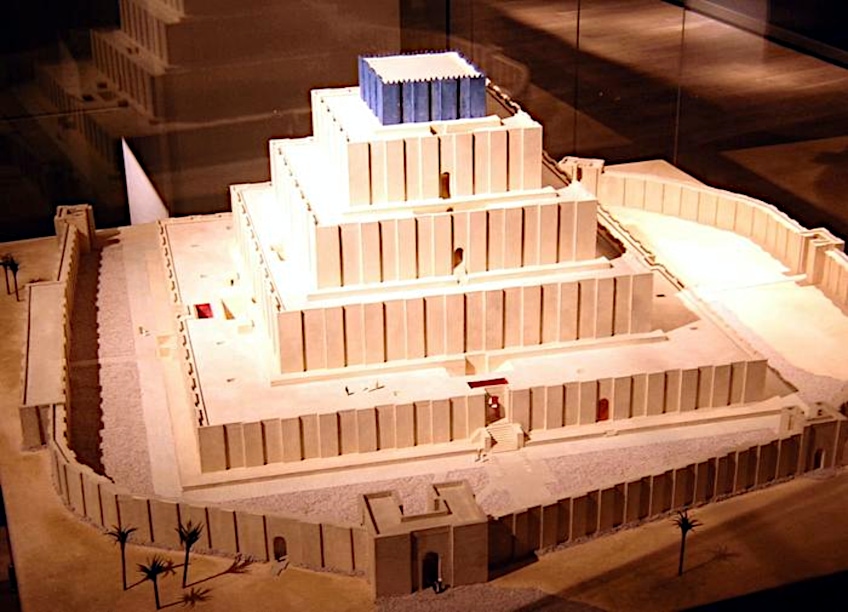

Chogha Zanbil (Around 1250 BCE) in Khuzestan

| Monarch | Untash-Napirisha (Around 1300 BCE) |

| Date Constructed | Around 1250 BC |

| Function | Temple and administrative center |

| Location | Khuzestan, Iran |

Chogha Zanbil is an ancient Mesopotamian site located in the Khuzestan province in Iran. It contains one of the only existing ziggurats outside of Mesopotamia. The culture that built it, the ancient Elamite civilization had an isolated existence in many ways. For instance, the language of the Elamites was not related to the languages around it. This makes it quite a unique place.

Model reconstruction of the Chogha Zanbil (c. 1250 BCE); Jona Lendering, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Model reconstruction of the Chogha Zanbil (c. 1250 BCE); Jona Lendering, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The ziggurat itself was built under king Untash-Napirisha. It was primarily built in honor of Inshushinak, the greatest of all the Elamite gods according to some sources. The town around which the ziggurat was built was named after the ruler who ordered its creation. The town itself is split into several major districts. The middle area holds various temples for other, lesser gods, and the outer area contains palaces and royal tombs. The inner area is where the ziggurat is located.

The city ceased all construction after the death of the king, and the whole area was soon abandoned but was later occupied until its ultimate destruction in 640 BCE. The city may have been an attempt by Untash-Napirisha to create a new religious center of the country, but it clearly didn’t survive after his death.

However, despite the city falling to ruin, the ziggurat is considered to be one of the best-preserved examples of this form of Mesopotamian-adjacent architecture. It is a mud brick-built, stepped structure that once measured 105.2 m (or 345 ft) on each side, and it was, roughly, 53 m (or 174 ft) tall. It was constructed out of five levels of the grand steps, and it had a temple on top (as was customary).

The ziggurat is the best preserved of its kind, and it is the best preserved despite only being 24.75 m (or 81.2 ft) high at the moment. This means that it is less than half as tall as it used to be, but as these structures are ancient and have all fallen apart, half the height is a very good thing to see.

Palace at Nimrud (Between 883 – 859 BCE) in Nineveh Governorate

| Monarch | Ashurnasirpal II (Before 883 – 859 BC) |

| Date Constructed | Between 883 – 859 BC |

| Function | Palace |

| Location | Nineveh Governorate, Iraq |

The Palace at Nimrud is an ancient Mesopotamian palace constructed in the middle of the city of Nimrud. This city became significant when Ashurnasirpal II decided to move the seat of his empire into the city. To do this, he needed to have a royal residence, and so a palace needed to be constructed. This piece of Mesopotamian architecture would eventually fall into disrepair during the 10th and 11th centuries BCE.

The palace itself was built using the labor of thousands of men. There was an 8-kilometer wall that surrounded the entire city and the palace, and there are many Mesopotamia drawings and inscriptions that adorn the limestone of the grand wall. We know more about the palace itself because of many of those inscriptions.

They discussed how the palace was constructed of various kinds of wood, such as cypress, boxwood, and juniper, and how there were various statues and other pieces of Mesopotamian art throughout the ancient structure. However, there were also extensive inscriptions describing what the king did to attain his power. He burned people alive, cut out the eyes and noses of his enemies, and even flayed the nobles who rebelled against him. So, while he may have been a powerful monarch, he likely wasn’t particularly beloved.

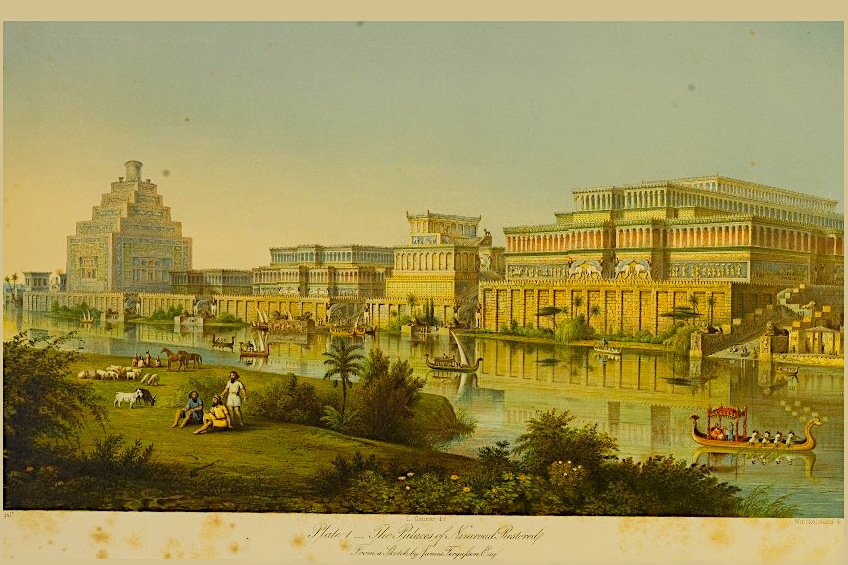

Artist James Fegusson’s 1853 impression of the Palace at Nimrud as imagined by the city’s first excavator, A.H. Layard (Between 883 – 859 BCE); w:James Fergusson (architect), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Artist James Fegusson’s 1853 impression of the Palace at Nimrud as imagined by the city’s first excavator, A.H. Layard (Between 883 – 859 BCE); w:James Fergusson (architect), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When his son, Shalmaneser III, came to power, he made an even larger palace in the city. It was twice as big, had more than 200 rooms, and it was complete with the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III (mentioned in the above section). This city was an important site for Mesopotamian architecture even though it was also the home of violent monarchs.

Ishtar Gate (Around 575 BCE) in Hillah

| Monarch | Nebuchadnezzar II (642 – 562 BCE) |

| Date Constructed | Around 575 BCE |

| Function | Gateway |

| Location | Hillah, Iraq |

The Ishtar Gate is an important piece of Babylonian architecture. It was originally constructed under the orders of Nebuchadnezzar II as one of the gates of the city of Babylon. It was a gorgeous structure that was built of glazed, blue bricks that were decorated with reliefs depicting animals and gods. Many of the other bricks were of differing colors to provide an utterly unique architectural impression on all visitors to the city.

Reconstruction of the tilework from the Ishtar Gate at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany (c. 575 BCE); LBM1948, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction of the tilework from the Ishtar Gate at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany (c. 575 BCE); LBM1948, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

During the reign of the king, he led the Neo-Babylonian Empire to its height. He was the Nebuchadnezzar of the Biblical narrative who captured Jerusalem. For this beautiful gateway, he dedicated it to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar and ensured that the presentations of other gods also adorned the walls.

Cedar wood was, supposedly, the material used for the roof and doors of the gate. The site would stand for a long time, but even the greatest of structures do not last forever, and it was severely damaged with time. However, at the end of the First World War, it was partially reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum. The reconstruction is not as large as the original, but the original can still be visited, it is simply not in a recognizable state any longer.

We have thus come to the end of our discussion of Mesopotamian art and architecture. We have examined both specific Mesopotamian artifacts and Mesopotamian buildings throughout this article, to provide an overview of the kinds of art and architecture that this ancient civilization once possessed. Hopefully, you have learned a few things about it. So, all that is left to be said is that we wish you a great day/week/month ahead, and always keep learning!

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the Mesopotamian Period?

Mesopotamia is an ancient region situated between and around the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, and the location is now predominantly part of Iraq. Some parts are also located in Iran, Syria, Turkey, and Kuwait. This ancient period began in about 3100 BCE, until the collapse of Babylon in 539 BCE. However, the area has changed hands many times throughout the millennia that have followed.

Which Civilizations Existed During the Mesopotamian Period?

The Mesopotamian era was comprised of several major civilizations. The Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians all formed part of Mesopotamia as a whole. The region later became dominated by the First Persian Empire, known as the Achaemenid Empire, and later by the Ancient Greeks.

What Does the Prefix Meso- Mean?

The prefix meso- is used in locations such as Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica, but what does it actually mean? This term is a Greek phrase that means the middle of something. So, Mesopotamia is in the middle of the potamos, or river. This means that it is a land between rivers, whereas when it is used for Mesoamerica, it means the middle of the Americas.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.