Famous Greek Paintings – Rare Survivors from Hellenic Antiquity

When it comes to the Greek arts, the casual observer would be forgiven for thinking that the ancient Greeks produced only sculpture and vases. That is because only a small fraction of the less durable artforms have survived the ravages of time. However, historians know from ancient sources that the Greeks not only produced paintings, but valued painting highly. Today, very little is known about this lost artform and the artists that produced ancient Greek paintings. In the article below, we will discuss what was significant about ancient Greek paintings, and take a look at some of the most famous works that have survived.

What Happened to Ancient Greek Paintings?

If few ancient Greek paintings are left for us to view, how do we find information on them? Most of the information that we have on Greek painters and artworks are from written records. A significant percentage the art ascribed to famous ancient Greek artists survive in the form of later Roman copies. The originals were either destroyed or deteriorated over time, and these replicas provide essential clues as to what the original artworks would have looked like.

Magna Graecia Sicilian painted tomb vase in the style of Attic painting (3rd – 2nd Century BCE); Ismoon (talk) (assemblage with Photoshop from two fragments of the image on display from the Met. Museum of Arts), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Magna Graecia Sicilian painted tomb vase in the style of Attic painting (3rd – 2nd Century BCE); Ismoon (talk) (assemblage with Photoshop from two fragments of the image on display from the Met. Museum of Arts), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The main reason why Greek paintings have not survived is that many paintings were created on wooden panels with tempera or wax paints. Since these materials are perishable, most of these works succumbed to natural processes of deterioration. Structures such as tombs that kept out harsh climactic conditions hold many of the murals and wall paintings that do survive.

Natural disasters such as the volcanic eruption of Thera, also created conditions where fragile paintings were preserved in layers of pumice and ash for millennia until they could be excavated.

Our most valuable resource for gaining insight into the broad range of styles and techniques of ancient Greek painters is the Greek fondness for decorating their pottery with paintings depicting everything from mythological events to everyday scenes. In addition, Greek artists were highly sought-after across the Ancient world and evidence of craftsmen traveling great distances to create masterpieces for foreign clients has been found across Europe and the Near East.

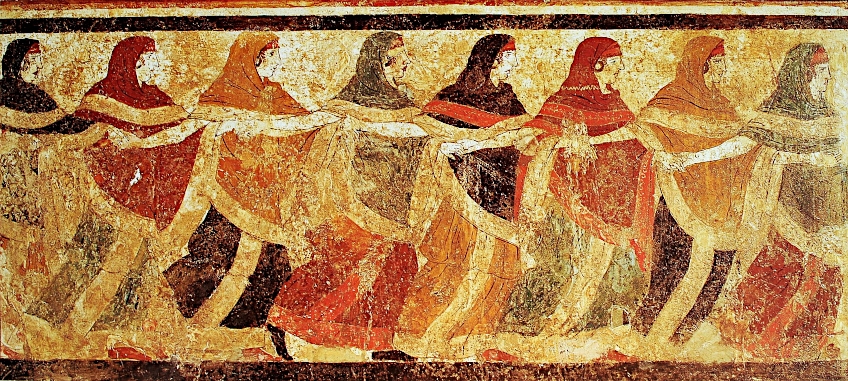

Fresco of dancing Peucetian women from the Tomb of the Dancers (end of the 5th Century BCE or middle of the 4th Century BCE); Naples National Archaeological Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco of dancing Peucetian women from the Tomb of the Dancers (end of the 5th Century BCE or middle of the 4th Century BCE); Naples National Archaeological Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

What Is Special About Ancient Greek Paintings?

What was significant about Greek paintings is that panel paintings were considered to be the art form artists worked with most often and were the most respected during the period according to ancient historians like Pliny and Pausanias. Portraits and still-lifes were among the subject matter depicted in these panels, produced with tempera and encaustic wax. The latter method was done by melting the wax before painting with it.

Encaustic gave artworks a lustrous sheen while also allowing the pigment to seep into a porous substrate, which is why it became a popular method for painting on stone statues as well. Sadly, not even replicas remain of these paintings due to the reasons stated previously.

Regarding paintings on ceramics and pottery, notable achievements were made in Attic vase painting during the Greek Golden Age in the middle of the fifth century BCE, especially in Athens. Most significantly, the red-figure painting technique that replaced black-figure painting, as well as considerable advancements in depicting the human figure, whether in motion or stillness, naked or clothed. Not only did Greeks paint on panel, architectural structures, and ceramics, but they also painted on sculpture.

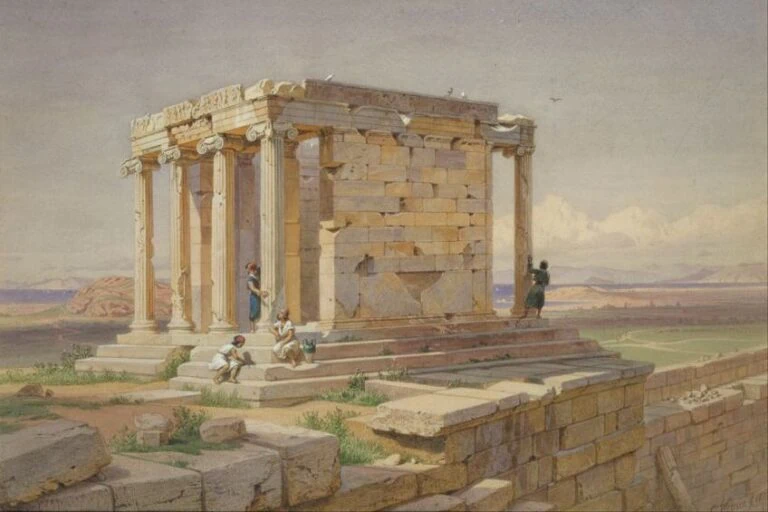

Painted architectural panel (late 6th-5th Century BCE); Getty Center, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Painted architectural panel (late 6th-5th Century BCE); Getty Center, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

These days, when we think of Greek sculpture and clothing we think of them as being white, but ancient Greek textiles were dyed in a multitude of colors, while buildings and sculpture were polychrome (meaning many colors). The Ancient Greek’s created environment was awash with bright colors, but due to time and weathering, these have mostly worn off or faded entirely.

By using laboratory techniques, small elements of ancient polychromy have been found by scientists and archaeologists on the surface of sculpture and statues.

Painting Education

During the Classical Period (480-323 BCE) in ancient Greece, we see the emergence of the Sicyon School of painting. Before, painters were usually trained by being assistants in a master painter’s workshop. Then Pamphilos (390 BCE – n.d.), a Macedonian painter started this painting school in about the middle of the fourth century at Sicyon.

The school had distinguished pupils, and by the end of the fifth century, they were painting from life and studying theory.

Geometry and arithmetic was included in the curriculum with Pamphilos insisting that they were essential to the proper painting practice. Painting and / or drawing eventually became an acknowledged subject in Greek education for boys.

Detail from the painted facade of the Macedonian tomb at Aghios Athanatios (325-300 BCE); Egisto Sani from Italy, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from the painted facade of the Macedonian tomb at Aghios Athanatios (325-300 BCE); Egisto Sani from Italy, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Greek Painters

Although almost no paintings of Classical Greek art have survived, apart from a few frescoes and vases, we do have some information about the artists and their paintings written by ancient Greek historians. A few of whom we will discuss below.

Cimon of Cleonae (c. 8th or 6th century BCE)

| Time Period | c. 8th or 6th century BCE |

| Famous Works | Titles unknown |

Cimon (c. 8th – 6th century BCE) came from the city of Cleonae and painted in early ancient Greece. He has been attributed with introducing folds and wrinkling in fabric, for inventing the artist technique of fore-shortened views, and for representing human figures in various positions, like looking upwards, downwards, sideways, and so on.

However, he was said to have lived during the 8th century, whereas foreshortening only appeared at the end of the 6th century in Greek art. In addition, two epigrams mention Cimon in the last part of the 6th century, hence the confusion with his dates.

Agatharchus (c. 5th century BCE)

| Time Period | c. 5th century BCE |

| Famous Works | Titles unknown |

Agatharchus (c. 5th century BCE), also known as Agatharch, came from Samos and was known for the rapidity with which he completed his paintings. He has been mentioned in the writings of Vetruvius (c. 80-15 BCE) as introducing scenic painting, but this contradicts Aristotle (384 – 322 BCE) who claimed that Sophocles (c. 496 – 406 BCE) invented scenic painting.

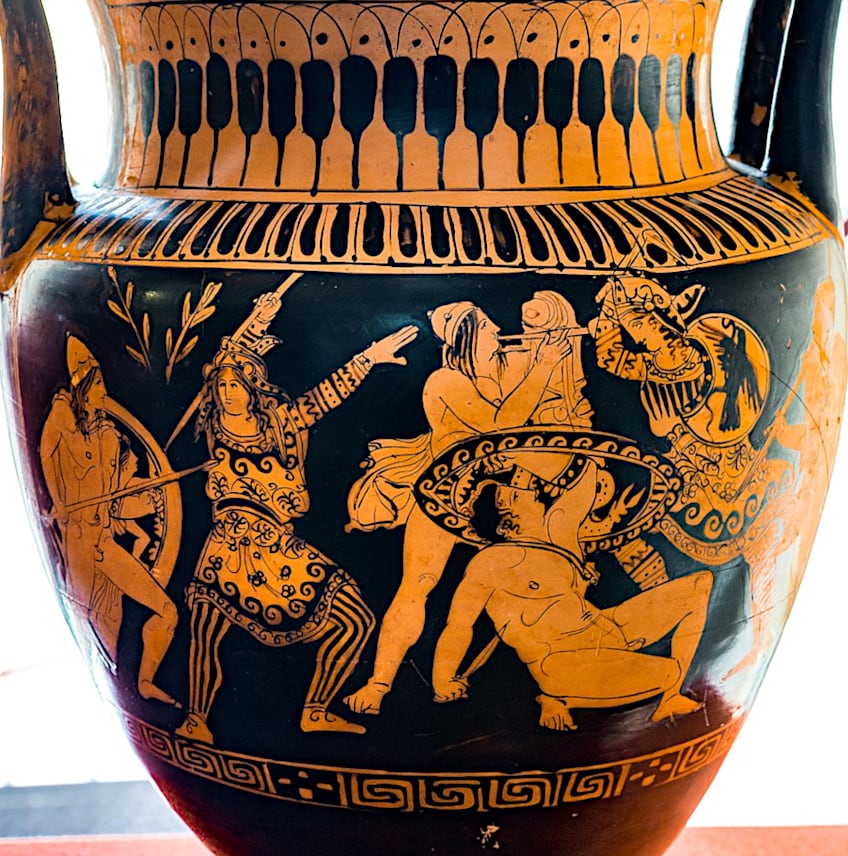

Attic red-figure column-krater attributed to the Pronomos Painter whose work has been described as inspired by the innovations of Agatharcus (c. 410-400 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure column-krater attributed to the Pronomos Painter whose work has been described as inspired by the innovations of Agatharcus (c. 410-400 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Agatharcus was credited with developing illusion and perspective in scenic painting and was believed to have been the first to use perspective on a large-scale, as well as introducing the idea that by placing objects towards the sun, one could bring out their shadows.

Apollodorus (c. 5th century BCE)

| Time Period | c. 5th BCE |

| Famous Works |

|

Apollodorus was an influential Athenian painter but whose works are now lost completely. He has been thought to be the first painter to shade his works and was therefore known by the name Sciagraphos, which means ‘shadow painter’. His paintings are mentioned in several ancient sources, with “Ajax Struck by Lightning”, “A Priest at Prayer”, and “Odysseus” being among them and which were all in Athens.

Zeuxis (c. 5th century BCE)

| Time Period | c. 5th century BCE |

| Famous Works | Titles unknown |

One of the most famous painters of ancient Greece was Zeuxis (c. 5th century BCE). He perfected the shadow technique after Apollodorus, creating a three-dimensional view in his works. It appears that he painted on panels rather than walls, preferring to paint small compositions that often contained one figure. He introduced a different subject into monumental works, genre painting, which heavily broke with tradition.

Zeuxis Selecting Models for his Painting of Helen of Troy by Angelica Kauffmann (c. 1778); Angelica Kauffmann, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Zeuxis Selecting Models for his Painting of Helen of Troy by Angelica Kauffmann (c. 1778); Angelica Kauffmann, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although his works have also not survived, ancient writers have recorded the subject matter of several of his paintings, such as Eros with a crown of roses, deities gathering around Zeus, Pan, and other images of gods. He also painted mythological figures, like centaurs, Heracles strangling serpents in front of his parents, and portraits of Homeric characters Menelaus, Helen, and Penelope.

His genre paintings supposedly included a boy with grapes, an elderly woman, an athlete, and a still life with grapes.

Famous Greek Paintings

The few examples left from ancient Greece limit our list of famous Greek Paintings, but we are nonetheless extraordinarily lucky to have a few original works to view. Below, we have listed some of these beautiful examples.

Akrotiri Frescoes (c. 16th century BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Akrotiri Frescoes |

| Date Painted | c. 16th century BCE |

| Medium | Fresco and/or tempera |

| Discovered | Akrotiri, Thera, Aegean Islands |

| Currently Housed | National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece |

These frescoes were from the Minoan Akrotiri settlement on the Island of Thera (now known as Santorini and were painted during the Bronze Age. They have survived because of an earthquake that took place between 1650 and 1550 BCE which led to a volcanic eruption, covering the settlement and the paintings meters deep in volcanic ash and pumice. The first excavations in 1967 revealed the lost city, allowing people to view these paintings.

Depiction of a Minoan town from Room 5 in the West House, Akrotiri (between 1650 and 1500 BCE); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Depiction of a Minoan town from Room 5 in the West House, Akrotiri (between 1650 and 1500 BCE); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Akrotiri frescoes were found in all types of buildings and sections, suggesting that people from various classes of society enjoyed them. The inside walls were covered with a coating of lime plaster, and then painted. This was done either when the plaster was dry with the tempera method, or while the plaster was fresh, making it a fresco. The use of mechanical devices is evidenced in the detail of some of the works where there are geometric designs or spirals for the artist to achieve greater accuracy. Pigments for paint such as red, orange, blue, black, purple, and white were derived from minerals and plants such as saffron, while a fixative was made with organic materials.

Detail of the Saffron Gatherers fresco from Akrotiri (1600-1500 BCE); Akrotiri, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail of the Saffron Gatherers fresco from Akrotiri (1600-1500 BCE); Akrotiri, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The subject matter and style of some of the paintings reflects the influence brought about by Thera’s thriving trade, which connected people from Mainland Greece, the Cyclades, Crete, and Egypt. A love for nature and the sea was often depicted with seascapes, fish, plants and animals, many represented in a naturalistic way. Spirals, curves and other abstract and geometric shapes were commonly used in painted scenes of day-to-day life like gathering saffron and crocuses and religious scenes.

These scenes are important for historians to study the clothes, hairstyles, jewelry, weapons, armor, landscapes, and architecture of the Bronze Age. Below, we will take a look at a few of the frescoes.

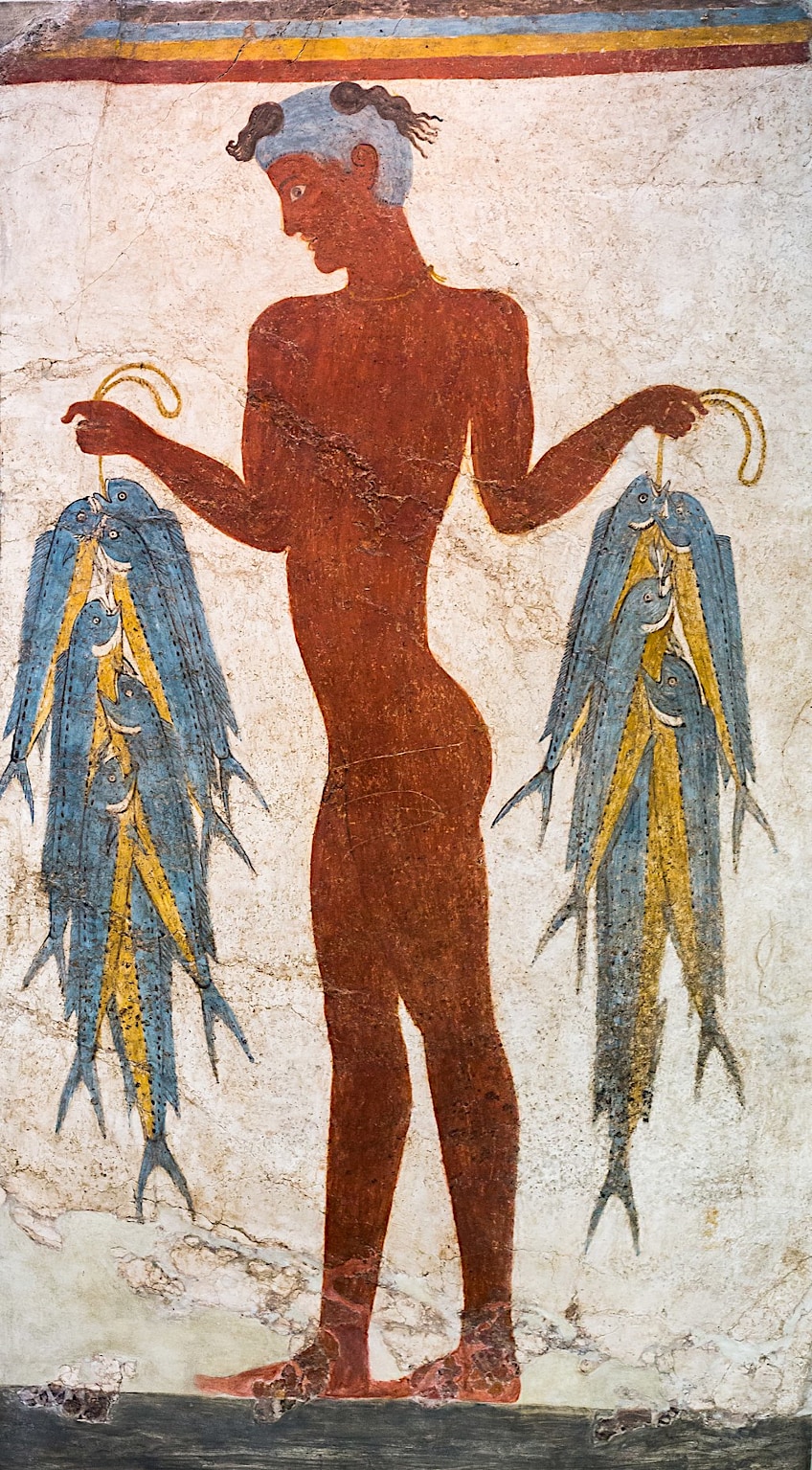

The Fresco of the Fisherman

In Room 5 of the West House, situated in the north-eastern corner one will find this fresco of a male figure carrying a cluster of fish in both hands. It is one of the most well preserved frescoes from Akrotiri, with a similar one painted on the wall next to it. Scholars have speculated that they may be youths performing a religious ritual. Both their heads are partially shaved and are both are nude.

Wall painting of young man carrying fish from Akrotiri (late Minoan IA); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Wall painting of young man carrying fish from Akrotiri (late Minoan IA); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The religious nature of the subject matter is supported by the presence of ritual pottery in the corridor joined to room five, as well as recesses in the room’s walls.

An offering table was found by archaeologists in the north-west corner toward which both the figures are walking, indicating that the fish they carry may be ritual offerings.

The Fresco of the Ladies

In the House of Ladies, this fresco was found in Room 2 and are actually two separate works. They are clothed in Minoan fashion with colored robes, jackets and kilts that expose the breasts.

Section of wall with depiction of a woman and papyrus plants from the House of the Ladies (c. 1700-1600 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Section of wall with depiction of a woman and papyrus plants from the House of the Ladies (c. 1700-1600 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Both women have long hair and are wearing makeup, as well as earrings and a necklace which suggests that they are high status. They could be taking part in a religious festival or activity, and above them is painted a starry sky. A third woman who may be helping the bending figure dress, but only fragments of the image are left; pieces of a dress and an arm.

The Fresco of the Lilies or Spring Fresco

Belonging to three walls in Room 2 on the ground floor of the Delta Building, this painting depicts volcanic rocks in various colors and growing among them may be lilies or papyrus. They are shown in various stages, from budding to blooming, and appear to be swaying in a light breeze.

Small room from Delta 2 in Akrotiri with freso depicting a Spring landscape (c. 1550 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Small room from Delta 2 in Akrotiri with freso depicting a Spring landscape (c. 1550 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

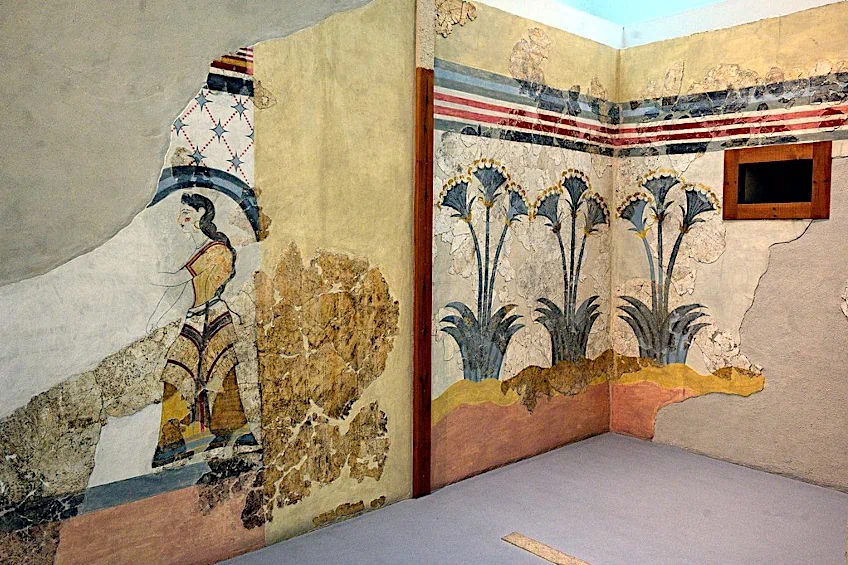

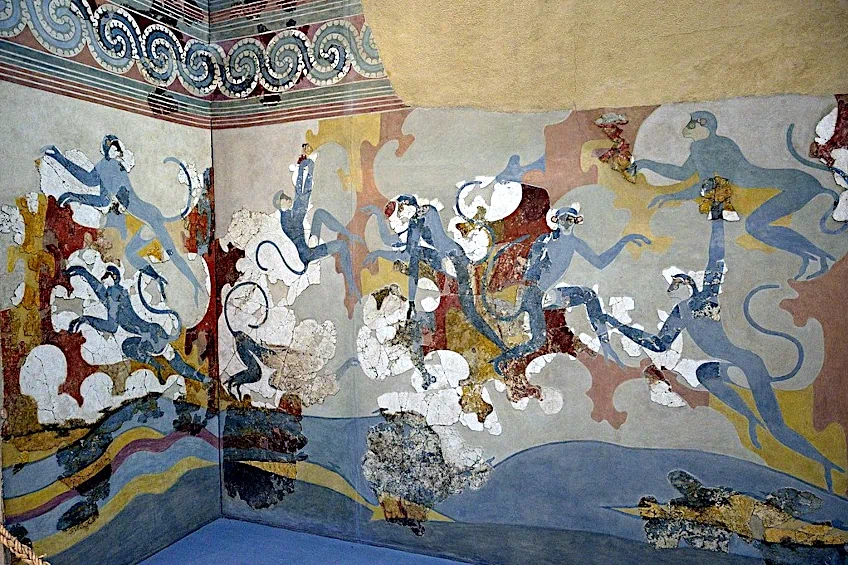

The Fresco of Monkeys

This fragmented piece from Room B6 depicts blue monkeys trying to escape two dogs by climbing rocks. Monkeys are often represented near sacred altars or as assistants to priestesses and can be seen in other examples of Theran and Minoan art.

The Blue Monkey fresco from room Beta 6 in Akrotiri (17th century BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Blue Monkey fresco from room Beta 6 in Akrotiri (17th century BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

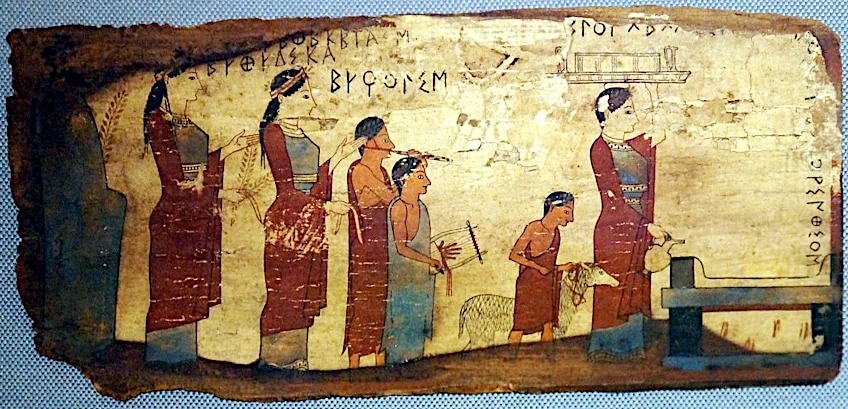

Pitsa Panels (c. 540 – 530 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Pitsa Panels |

| Date Painted | c. 540 – 530 BCE |

| Medium | Mineral pigments on stucco on board |

| Discovered | Pitsa, Corinthia, Greece |

| Currently Housed | National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece |

The Pitsa Panels (c. 540-530 BCE), also known as the Pitsa Tablets are believed to be the earliest surviving Greek paintings on panel. The wooden tablets are covered with stucco, a type of plaster, and painted with mineral pigments. The vibrant colors blue, red, yellow, black, white, and green are remarkably well-preserved.

No shading or gradation was used to create the images. The black outlines seem to have been applied first and then filled in with color.

What makes this group of panels significant is that most ancient Greek paintings that have survived are vase paintings or frescoes, and thus to be able to view these tablets is quite special, especially since panel paintings were held in such high regard in Ancient Greek arts.

Pitsa Panel (c. 540-530 BCE); Schuppi, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Pitsa Panel (c. 540-530 BCE); Schuppi, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As for the subject matter on the panels, they depict religious scenes linked to the nymph cult. One of the two almost complete pieces portray a sacrifice being made to the nymphs. On the right of the image, three or more female figures approach an altar, wearing peplos and chiton. Musicians playing the aulos and lyra accompany them. The figure closest to the altar seems to be pouring a liquid offering from a jug, while another figure leads a sacrificial lamb to the altar.

Achilles and Ajax Playing a Board Game (540 – 530 BCE)

| Artist Name | Exekias (before 550 – c. 525 BCE) |

| Artwork Title | Achilles and Ajax Playing a Board Game |

| Date Painted | 540 – 530 BCE |

| Medium | Terracotta amphora |

| Discovered | Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Vatican City, Italy |

| Currently Housed | Vatican Museum, Rome, Italy |

This example of black-figure pottery from the Archaic period depicts, as its title suggests, Achilles and Ajax playing a board game painted on an amphora. The artist who signed this piece, Exekias (before 550-c. 525 BCE) was both a potter and a painter who was active in Athens during the sixth century BCE.

Attic amphora with a depiction of Achilles and Ajax playing a board game by Exekias (c. 530 BCE); Exekias, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic amphora with a depiction of Achilles and Ajax playing a board game by Exekias (c. 530 BCE); Exekias, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Geometric patterns frame the narrative scene depicting the two greatest Greek champions, Achilles and Ajax as they keep themselves occupied with a game during an interval in the Trojan War. The scene looks uncharacteristically peaceful during a time of war, as the two heroes bend over the small table with their spears in one hand and the other moving pieces on the board.

The figures are black silhouettes against a light background, their lines precise and the curve of their bodies clear and crisp. Within the forms details are achieved with careful incision, as seen in Achilles’ armor and the figures’ hair and cloaks.

Terracotta Amphora (c. 490 BCE)

| Artist Name | The Berlin Painter |

| Artwork Title | Terracotta Amphora |

| Date Painted | c. 490 BCE |

| Medium | Red-Figure painting on terracotta |

| Discovered | Nola, Italy |

| Currently Housed | Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

This Terracotta Amphora (c. 490 BCE) is attributed to the Berlin Painter, the common name given to a certain painter of Attic Greek vases who was active from c. 490 to the 460s BCE. Amphoras were storage jars with two handles that held wine, milk, oil, or grain. They were also sometimes used as grave markers and as vessels for human remains.

In terms of Greek vase paintings, this particular work is considered a masterpiece as it combines various aspects of Athenian culture in a high quality artwork.

The shape of the amphora is elegant with a glossy glaze, and depicts a singer on the obverse playing a kithara, a type of lyre, while on the other side is depicted a musical contest judge holding a long wand. Movement created by the music is portrayed in the curve of the singer’s long tunic.

Terracotta amphora with a depiction of a singer playing a kithara on one side and a competition judge on the other ascribed to the Berlin Painter (c. 490 BCE); Berlin Painter, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Terracotta amphora with a depiction of a singer playing a kithara on one side and a competition judge on the other ascribed to the Berlin Painter (c. 490 BCE); Berlin Painter, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tomb of the Diver (c. 470 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Tomb of the Diver |

| Date Painted | c. 470 BCE |

| Medium | Fresco on plaster on limestone |

| Discovered | Paestum, Magna Graecia, Italy |

| Currently Housed | National Museum of Paestum, Capaccio, Italy |

In Magna Graecia, close to the city of Paestum was found the Tomb of the Diver (c. 470 BCE) in 1968. This tomb is important as the wall paintings it contains is the only surviving complete example from the Archaic, Orientalizing and Classical Greek periods. The tomb was constructed in the city of Poseidonia, a Greek city which later became Paestum in the time of the Romans.

The tomb was built with limestone and covered with plaster on which the frescoes were painted. The design was first incised into the plaster and then red lines were added to create the image, and blue, green, red, black, and white were the colors used for the painting. Black was used at the end of the painting process to outline the figures and add detail.

Detail of the symposium scene from the Tomb of the Diver (c. 470 BCE); Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail of the symposium scene from the Tomb of the Diver (c. 470 BCE); Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Depicted on the longer walls of the tomb are images of a symposium, with figures on couches and vessels for mixing wine. Each figure is crowned and is covered up to the waist. One male figure is shown on the north wall about to play the game, kottabos. While on the south wall, a lyre is held by a male figure as two figures sit conversing on a couch. The walls of the tomb are covered by other various images.

The image after which the tomb is named is situated on a slab that is the roof. On it is depicted a diver, an image which is very much unknown in ancient Greek art.

The diver’s anatomy is detailed, with clear complicated lines and a small amount of hair growing from his chin, indicating that he is a young adult. It is thought that the diver serves to symbolize the moment of death, as one leaps from one reality to another, but researchers have interpreted it in various ways.

Odysseus and the Sirens (480 – 470 BCE)

| Artist Name | The Siren Painter (c. 5th Century BCE) |

| Artwork Title | Odysseus and the Sirens |

| Date Painted | 480 – 470 BCE |

| Medium | Red-figure pottery |

| Discovered | Vulci, Northern Lazio, Italy |

| Currently Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

This siren vase is what is known as a stamnos, a wine jar used by the ancient Greeks that has a wide opening and two handles on the shoulders of the jar. The identity of the artist who produced this particular stamnos is unknown but has come to be called the Siren Painter due to the recurring artistic style, suggesting that these characteristics belong to a single artist.

This red-figure painted vase depicts Odysseus’ ship as it passes the island inhabited by the Sirens. A narrow strip of black shading in the foreground represents the sea, with curves that are outlined in black as well.

The ship is heading to the left as figures, with only their heads visible, propel it forward with oars. A male figure stands at the front, on the stern of the ship, guiding the oarsmen. At the bottom of the mast, we see Odesseus fastened with his hands behind his back as he looks up toward the sky or the Siren flying down towards the ship. Rocky cliffs are depicted on each side of the composition, each one with a siren perched on the edge, watching the scene.

Attic red-figure stamnos with a depiction of a scene from the Odyssey attributed to the Siren Painter (c. 480-470 BCE); English: Siren Painter (eponymous vase), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure stamnos with a depiction of a scene from the Odyssey attributed to the Siren Painter (c. 480-470 BCE); English: Siren Painter (eponymous vase), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

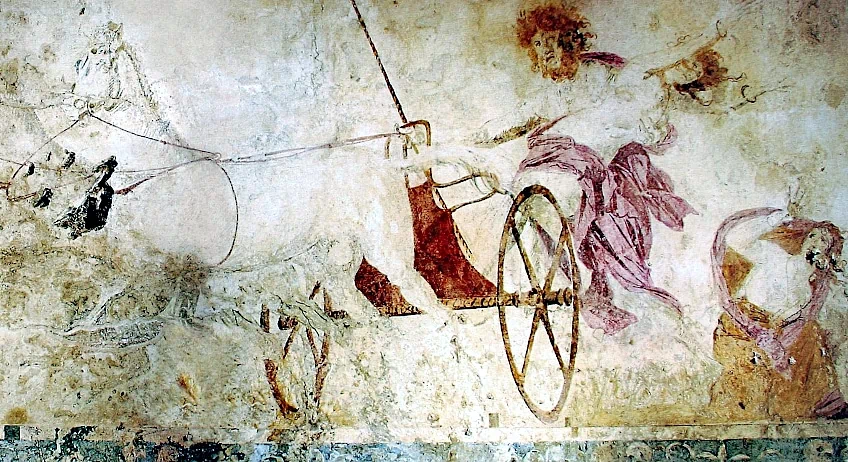

Hades Abducting Persephone (c. 340 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Hades Abducting Persephone |

| Date Painted | c. 340 BCE |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Discovered | Royal Tomb in Vergina, Greece |

| Currently Housed | Museum of the Royal Tombs, Vergine, Greece |

This fresco of Hades Abducting Persephone (c. 340 BCE) was found in the small royal tomb at Vergina belonging to King Phillip II (382 – 336 BCE). The modern village of Vergina was once the royal capital of Macedon in ancient times, known as Aigai.

Although the painting has greatly deteriorated over time, the scene can still be distinguished.

The fresco is situated in Tomb I and depicts Hades in a red chariot as he gets away with Persephone. There is a lot of movement in the image, with the detailed drapery around her waist moving in the wind, while she holds her arms in the air, flailing about in distress. A nymph can be seen in the bottom right corner of the composition cowering in fear of the moving chariot.

Tomb fresco depicting Hades abducting Persephone (340 BCE); from Le Musée absolu, Phaidon, 10-2012, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tomb fresco depicting Hades abducting Persephone (340 BCE); from Le Musée absolu, Phaidon, 10-2012, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Philip II and His Son Alexander the Great (4th century BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Artwork Title | Philip II and His Son Alexander the Great |

| Date Painted | 4th century BCE |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Discovered | Royal Tomb in Vergina, Greece |

| Currently Housed | Museum of the Royal Tombs, Vergine, Greece |

On the front of the same tomb as the fresco above, we find the fresco of Philip and Alexander the Great. Running across the facade above the entrance, a hunting scene is depicted with two figures on horseback. It is believed that the older male figure is Philip II and the younger one is his son, Alexander the Great. This painting is in poor condition, but it remains one of the best examples of Greek paintings.

That concludes our dive into the world of famous Greek paintings. Although there are few paintings left for us to view, we are lucky to have such beautiful surviving examples. If you enjoyed this article, we encourage you to further your journey into Classical Greek art and ancient Greek painters, as well as other forms of Greek artworks!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Significant About Greek Paintings?

What makes Greek paintings special is that according to ancient historians like Pliny and Pausanias, panel paintings were considered to be the art form that artists worked with most often, and was the artform that was most respected during the period. Notable achievements were made in Attic vase painting during the Greek Golden Age in the middle of the fifth century BCE. The red-figure painting technique replaced black-figure painting, and considerable advancements were made in depicting the human figure.

What Happened to Greek Paintings?

A large reason why Greek paintings have not survived is that many wall paintings were painted on wooden panels with tempera or wax paints. Much of the art that we have left today are Roman replications of the original Greek artworks that were either vandalized, destroyed, or simply deteriorated over time, and these replicas give us insight into the techniques and styles used by the ancient Greeks.

Did the Ancient Greeks Paint on Sculpture?

The ancient Greeks not only painted on vases and frescoes, but they also painted on sculpture and statues as well. We often think of ancient Greek sculpture as being devoid of color, but that is because the paint faded and wore away over time. In fact, sculptures were quite colorful, and by using laboratory techniques, small elements of ancient polychromy have been found by scientists and archaeologists on the surface of sculpture and statues.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.