Battle of Crécy – Early English Gains in the Hundred Year’s War

The Battle of Crécy was one of the most pivotal clashes to have occurred during the Hundred Years’ War. This was the discontinuous conflict fought between the English and their French neighbors for little over a full century. Lasting from 1337 AD to 1453 AD, the war was fought on both military and political lines, though the former only ever occurred on French soil. This medieval period saw many legendary skirmishes and battles, one of the most notable being the one that occurred near the French town of Crécy on the 26th of August, 1346. The battle saw the English allied with troops from both Wales and the Holy Roman Empire, fighting against an army of French, Majorcan, and Genoese soldiers. Led by King Edward III, the invading English force would see victory over their enemies despite a substantial numerical disadvantage – a feat that would be echoed by the brave King Henry V 69 years later during the Battle of Agincourt. Continue reading for a broader dissection of the Battle of Crécy.

Historical Significance of the Battle of Crécy

Heeding the lessons learned from their Saxon ancestors who reclaimed England from the days, and from their more contemporary history of conflict against Scotland, Edward III’s army would employ its knowledge regarding the importance of availing advantageous terrain and strategic flexibility to demolish a much larger fighting force.

One of the lessons learned from this decisive victory in particular regarded the effectiveness of the English longbow and how formidable it was as a weapon when employed in great numbers. For many historians, the battle also signified what could be described as a prelude to the diminishment of chivalry on account of how many injured soldiers were routed and slaughtered by peasants once the fighting had ceased.

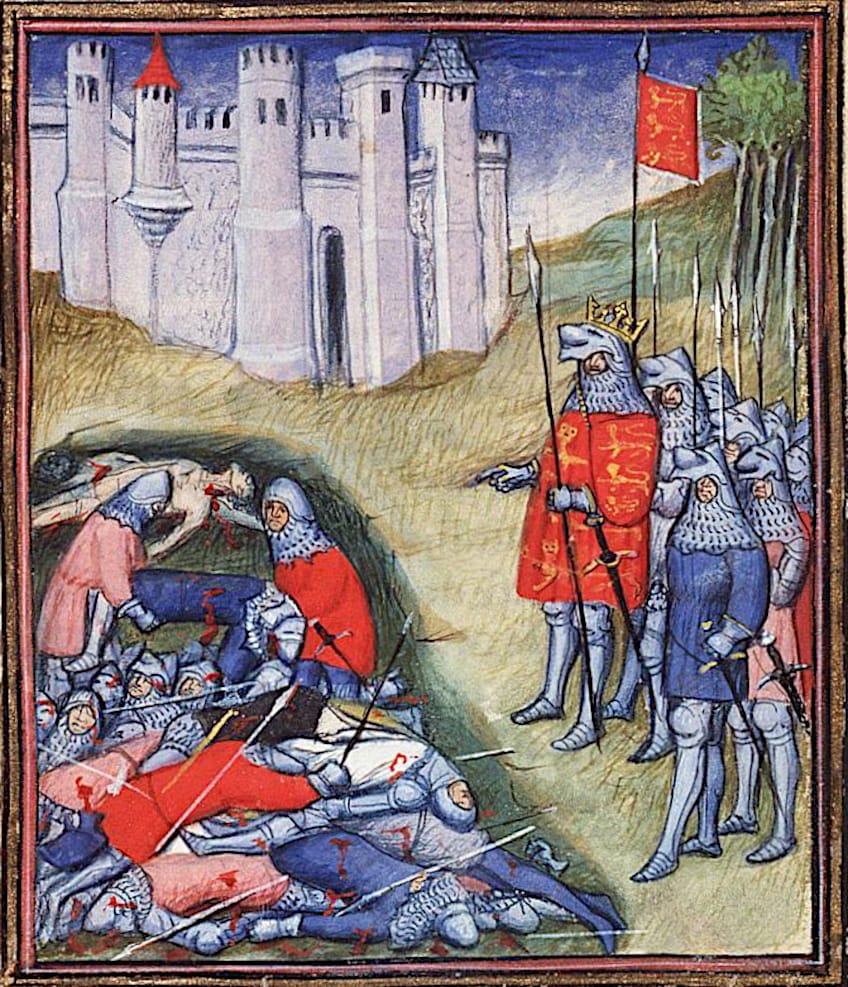

Manuscript illustration depicting Edward III counting the dead on the battlefield of Crécy from Jean Froissart, Chroniques Vol. I (c. 1410); Virgil Master (illuminator), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Manuscript illustration depicting Edward III counting the dead on the battlefield of Crécy from Jean Froissart, Chroniques Vol. I (c. 1410); Virgil Master (illuminator), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

One of the many other consequences of the battle was the capitulation of the French port town of Calais, which, without an army to support its defense against the English, would be seized in the following year. The walls of Calais would remain host to the English for more than two centuries and eventually become the place to welcome King Henry V and his army to safety following his victory at the Battle of Agincourt.

| Name of the Battle | The Battle of Crécy |

| Overarching Conflict | The Hundred Years’ War |

| Date | 26th August 1346 |

| Location | Crécy, France |

| Combatants | England versus France |

How Did the Battle of Crécy (1346) Come To Be?

In the middle of the 14th century, King Edward III retained dominion over large portions of France. His titleship, however, came at the cost of him becoming a vassal to the King of France, Philip VI. Despite either king being equals according to the law of the land, Edward III’s position as a vassal in France made him liable to the conditions of paying allegiance and homage to the French King. The tensions caused by this arrangement would only be further stoked by France’s support of the Scots during their war with England. To make matters worse yet, England supported the efforts of the Flemish, with whom it was closely tied in trade, against the French.

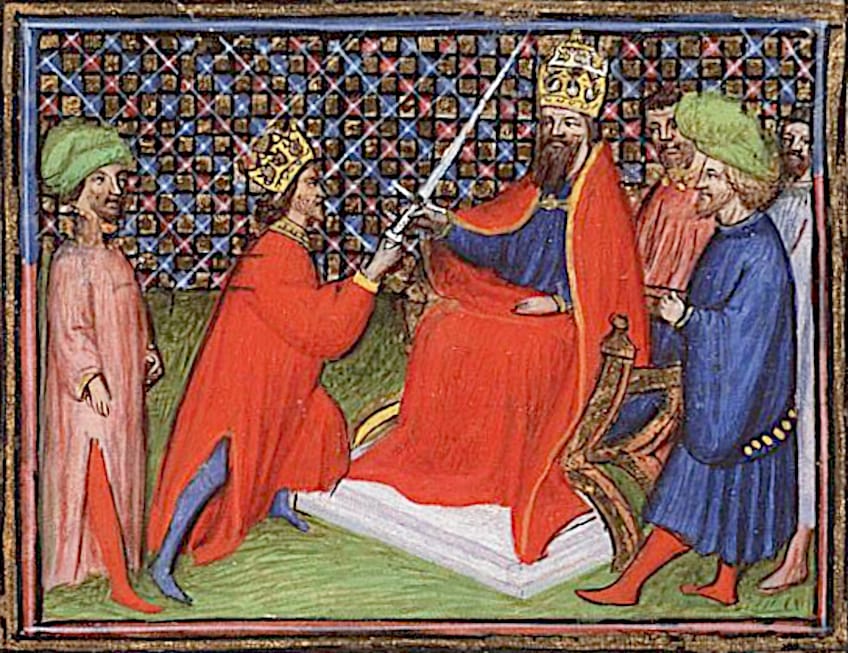

Depiction of Edward III of England paying homage for Aquitaine to French King Philip VI Valois by Jean Fouquet, from Grandes Chroniques de France (c. 1460); Levan Ramishvili from Tbilisi, Georgia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Depiction of Edward III of England paying homage for Aquitaine to French King Philip VI Valois by Jean Fouquet, from Grandes Chroniques de France (c. 1460); Levan Ramishvili from Tbilisi, Georgia, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Brewing Resentments

For Edward, a key inciting incident that would inspire vitriol toward the French King would be Philip VI’s welcoming of his ally David II of Scotland to seek refuge in France following defeat against the English at Paladin Hill in 1333. Philip VI would then demand that any subsequent negations between England and France take into consideration the interests of Scotland, a move that would forever sully Edward III’s sentiments toward Philip VI.

Manuscript depiction of David II, King of Scotland and Edward III, King of England from British Library MS Cotton Nero D VI, folio 66v (14th century); Unknown authorUnknown author., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Manuscript depiction of David II, King of Scotland and Edward III, King of England from British Library MS Cotton Nero D VI, folio 66v (14th century); Unknown authorUnknown author., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This would incentivize his invitation for the French Count Robert Artois to seek refuge in England following his sentencing to death over the murder of his aunt in 1336, a move that incensed Philip VI who had declared foe to any who would dare shelter the Count. When the French King then sent a missive demanding the relinquishment of the harbored fugitive only to be sternly declined, both sides began preparing for war.

By the year 1337, King Philip VI had reached his breaking point. Since both Edward III and Artois were both in England and thus far from the lawful jurisdiction of Philip VI, the French King’s immediate retaliation was to confiscate from Edward III the legitimacy of his ownership over the land he held in the kingdom’s southwestern region. In Philip’s decree wherein he dissolved Edward III’s legal claim to Aquitaine, it was stated that the decision was made “… because of the many excesses, rebellious and disobedient acts committed by the King of England and against Us and Our Royal Majesty.”

Portrait of Philip IV of France and family (14th Century); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Philip IV of France and family (14th Century); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

With the support of Flanders, King Edward’s response was to contest the legitimacy of Philip’s claim to his own throne. According to Edward III, the fact that his sister was the daughter of the prior King of France, it was he that held true titleship to the French crown. Although his claims to Philip’s throne were done chiefly in order to reinforce his rights to land in France, the intensity with which he pressed the matter would leave a legacy that would spur the decisions to act on France of his later successors. Nevertheless, this moment is largely considered to be when the Hundred Years’ War would come to start with the Battle of Crécy being one of several notable clashes between the two kingdoms.

First Blood

The initial start of military conflict began nearly instantly after such souring of relations, with the French striking the first blow in 1339 by sending raiding parties into English-owned Gascony, taking advantage of its dwindled garrison. Concurrently, Edward III sailed to Flanders where he bought the allegiance of the Holy Roman Emperor Ludwig. He would also lead an army of 12000 soldiers through the Northeast of France in the same year.

Illustration depicting Edward III becoming Vicar to Emperor Ludwig from Jean Froissart, Chroniques Vol. I; (c. 1410); Virgil Master (illuminator), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration depicting Edward III becoming Vicar to Emperor Ludwig from Jean Froissart, Chroniques Vol. I; (c. 1410); Virgil Master (illuminator), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Brief as the campaign was, it involved the implementation of a tactic that would come to be known as the chevauche, which was a means through which uncostly raids could destabilize and hamper the economic productivity of their enemies. King Edward III’s chevauches would not only remunerate him with substantial wealth but also cause a rift between King Philip VI and his subjects who would call into question his viability as a monarch when he was so readily unprepared to defend them. The toll it took on the coffers of the French Crown was considerable and the cost would inhibit Philip VI’s ability to maintain the full efficacy of his fighting force, as was the intended purpose.

But, by the year 1340, the costs of these campaigns would come to hurt the English King as well who saw no other means of maintaining his ability to wage war than by raising new taxes back home, doing so after formally declaring himself King of France whilst in Gent in the first month of that year. Once back in England, Edward III used the income gained from the wealth accrued through the new tariffs to assemble an armada of over 150 warships, most of which were originally merchant vessels he converted into barges suitable for battle against the numerically stronger French fleet that frequently attacked English settlements along the channel dividing both nations. In spite of the hesitance of his advisors, Edward III saw to sailing his ships to meet the French armada as it was docked in modern-day Belgium. And despite being fewer in number, the English fleet saw a remarkably decisive victory over their enemy.

A miniature of depicting the Battle of Sluys from Jean Froissart’s Chronicles (15th Century); Jean Froissart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A miniature of depicting the Battle of Sluys from Jean Froissart’s Chronicles (15th Century); Jean Froissart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Although the jury remains out on exactly how many French soldiers were slain in the confrontation, which later became known as the Battle of Sluys, it is believed that the number ranged between 10000 and 20000 – a crippling blow to the French King who found evermore reasons to put an end to his rival monarch. Edward III had very little time to savor the taste of his victory, however, as soon thereafter he would have to sail back to England to quell the civil unrest that had brewed on account of the heightened taxes that funded his war.

With the English King and his army now out of French territory, the Hundred Years’ War entered a proxy stage when the Duke of English-run Brittany passed away in April of 1341. A battle of succession soon ensued between his France-siding niece Jeanne of Blois and English loyalist half-brother John of Monfort. With Brittany being both a strong trade ally of the English and a part of France, both kings saw the need to intervene.

Miniature depicting the death of the Duke of Brittany in 1341 (15th Century); Jean Froissart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Miniature depicting the death of the Duke of Brittany in 1341 (15th Century); Jean Froissart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At the start of the conflict, it seemed as if France would take victory but this all changed when Edward sailed a small fleet to Brittany where his chevauches saw to the effective removal of any threat to England’s ownership of the duchy. Several months into the campaign, King Edward III returned to England after envoys from the Papal States brokered a three-year truce between the nations. Only a year later, however, peace talks held in France would fall through after neither king would concede to the demands of the other. The war, it seemed, would continue.

Portrait of Edward III from his tomb in Westminster (late 14th century); AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Edward III from his tomb in Westminster (late 14th century); AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

What came to follow over the next few years were frequent English incursions into French territory, starting with a military foray amassed in Gascony. Led by the Earl of Derby, Henry of Grosmont, the inquisition would retake land from the French and defeat a stern counterattack led by Louis of Poitiers. The victories brought through this would allow the English King to regrow the strength of his armies and prepare him and his men to set foot in France once again.

The Road to Crécy

In July of 1346, King Edward III sailed from Porchester to La Hogue in Normandy, a region that had yet to be scathed by his warpath. This posed a serious threat to King Philip IV, who depended on Normandy’s prosperous economy for taxation. After a night’s rest along the coast, the English army rode inland, launching devastating chevauches until eventually reaching the town of Caen. Despite its near-immediate capitulation, the English troops sacked the town for nearly three days, leaving over 3000 citizens dead in their wake before marching inland towards the capital city of Paris. Hearing of Edward III’s approach, King Philip IV began amassing a large army in San Denis.

Miniature depicting the landing of king Edward III in Normandy (15th Century); Maître du Boèce (Enlumineur) ; in Jean Froissart (1337-1410), Chroniques (Auteur), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Miniature depicting the landing of king Edward III in Normandy (15th Century); Maître du Boèce (Enlumineur) ; in Jean Froissart (1337-1410), Chroniques (Auteur), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Much to the French King’s chagrin, his forces were not readied by the time Edward III reached Poissy from where he led troops to burn two towns within eye’s view of the French capital. Learning of Philip’s preparations for war, Edward III redirected his troops northward towards the Somme where he thinly managed to avoid being pinned against its waters by the French. One across the river, the English army set up camp within the forest region near Crécy. The respite of their encampment, however, was a fleeting break from the conflict as Philip IV’s armies drew nearer.

The Battle of Crécy (1346)

With the French army now at his heels, King Edward III had no other option than to ready his own for battle. Edward and his army rested for the night atop a ridge, as they prepared to meet Philip IV’s contingents the following day. The ridge would later prove to be of invaluable tactical advantage.

Military Strength of Either Side

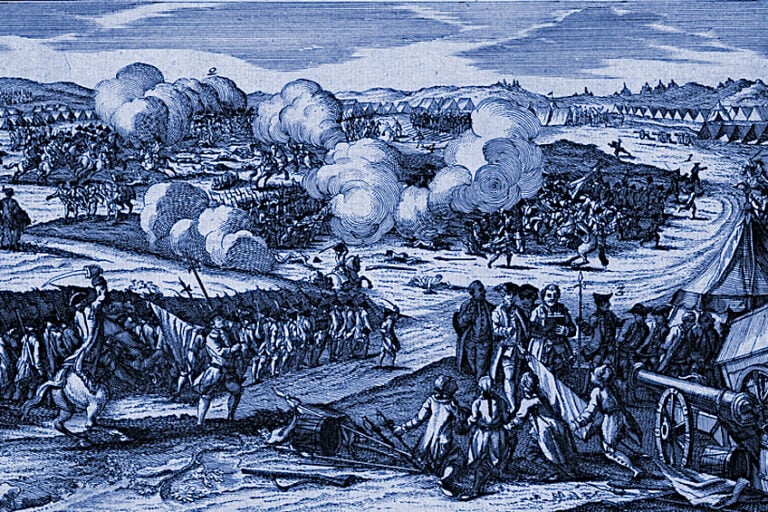

Although we cannot say for certain how many men comprised its ranks, renowned historian Andrew Ayton places the number between 7000 to 10000. According to his closest estimations, the number of men-at-arms would have been around 2500; these would have included both knights and nobles, all of whom would be convoyed by their own retinues of heavily armored soldiers. Included in the English fighting force would also be around 5000 longbowmen and 3000 hobelars, the latter of whom were lightly armored cavalrymen and archers on horseback most often employed for skirmishes. There would also have been around 3500 spearmen whose reach of their weapons would account for a longer reach and thus a stronger capacity to hold a line. These numbers, you may notice, do not add up to the supposed fighting force of 7000 – 10000. This is because academics have in past contested the figures, leaving us with the aforementioned approximation.

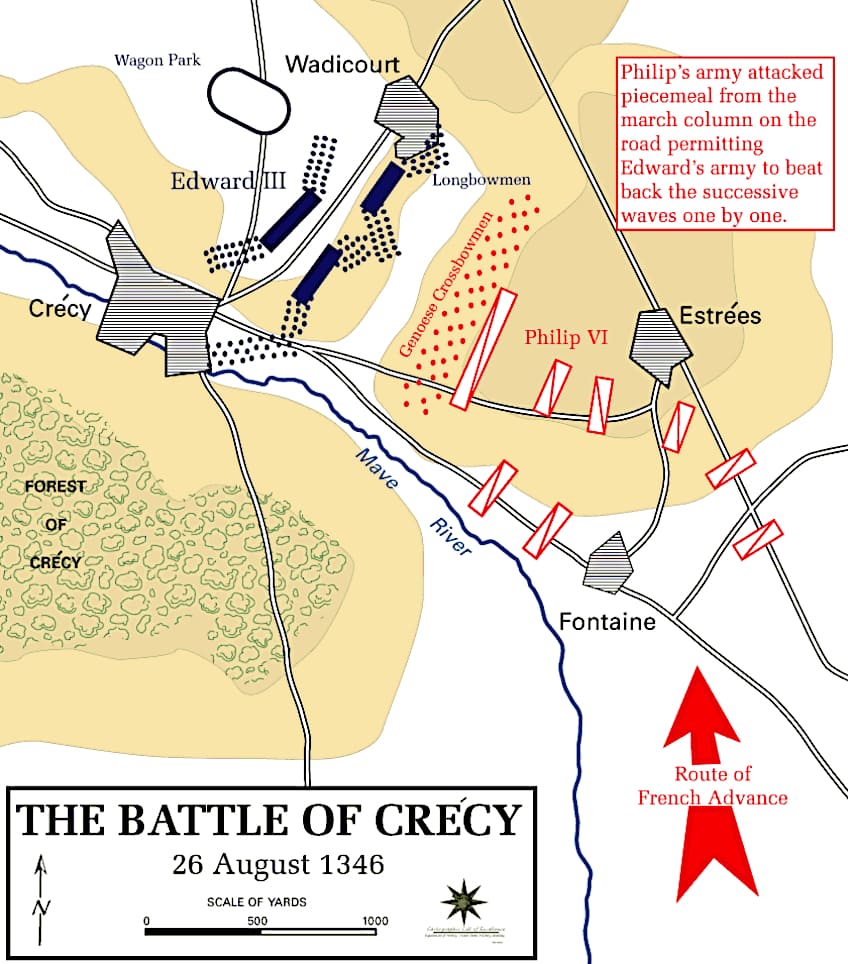

Battle formations at the Battle of Crécy; https://westpoint.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/academics/academic_departments/history/Modern%20Warfare/battle_crecy.gif, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle formations at the Battle of Crécy; https://westpoint.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/academics/academic_departments/history/Modern%20Warfare/battle_crecy.gif, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gathering estimates for the fighting strength of the French, on the other hand, is a much trickier task to achieve on account of the fact that the Crécy campaign’s records of finance have been lost to the annals of history. We do, however, have more than enough historical records to indicate that the French outnumbered their enemy by a massive margin. The predominant consensus among historians places the number of French soldiers at about 30000 men strong.

Manuscript miniature of the Battle of Crécy (14th Century); Gilles Li Muisit, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Manuscript miniature of the Battle of Crécy (14th Century); Gilles Li Muisit, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

How Did the Battle of Crécy (1346) Play Out?

As the French army drew closer, King Edward III mobilized his units to an elevated ridge resting in between Crécy and Wadicourt. The ridge faced southward towards the valley through which Philip IV and his men were marching in their direction. The positional advantage of the ridge afforded greater protection from the French archers and would stunt any cavalry charge’s ability to overwhelm Edward III’s lines. Edward III positioned his dismounted melee soldiers in the middle of the formation.

Edward III had his cavalries posted on either flank of the men-at-arms, with the left unit led by the earls of Northampton and Arundel and the right by his then sixteen-year-old son Edward of Woodstock, famously known as the Black Prince. Posted before the English line were rows of stakes, trenches, and pits to offer the army greater defensive capabilities. King Edward III positioned himself with the reserve division behind the foremost ranks by a windmill whose elevation provided him with a thorough viewpoint of the armies.

The Significance of the English Longbow

Positioned on either wing of the army were the acclaimed English longbowmen, whose lethality and battle efficacy was the stuff of legend. Each archer was equipped with bodkin arrows, whose heads were more than capable of piercing the armored plates of knights. Beyond that, the skill of the English archers was unrivaled across medieval Europe.

Since the reign of Edward I, every village in England was expected to contribute men to the kingdom’s national reserve of archers, all of whom would be expected to undergo weekly training in the use of the longbow. As we are soon to explain, such an expense proved indispensable in battles such as this.

The French Attack

The French approach commenced in the late afternoon, closing in at 6 pm. This was despite the full fighting force of his army not having yet arrived to strengthen his numbers. It is likely that Philip IV would have ideally waited for their arrival before pressing forward, but the itchiness for battle of the nobility pressured him into an early advance. Caught in the wave of the arrogant impatience of his knights and their leaders, Philip IV then prepared for battle before the bulk of his infantrymen and baggage could join him. In succumbing to the chivalric conceit of his men, King Philip’s lack of control would doom him to failure.

Manuscript miniature depicting the Battle of Crécy from the Grandes Chroniques de France (c. 1415); Workshop of Master of Boucicaut, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Manuscript miniature depicting the Battle of Crécy from the Grandes Chroniques de France (c. 1415); Workshop of Master of Boucicaut, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The first wave of troops to attempt an ascent of the ridge were Philip’s crossbowmen, comprised of both French and Genoese. However, without having waited for the supplies to have arrived beforehand, the men had to approach without the pavise shields they relied on for protection from counter-fire as they reloaded. Worse yet, it began raining as they marched forward. A brief yet thunderous downpour began pelting the bowmen, inundating their drawstrings and rendering their crossbows unfit for use.

Illustration depicting the Battle of Crécy from Ms 659 f.255 r (1477); AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration depicting the Battle of Crécy from Ms 659 f.255 r (1477); AnonymousUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This was an issue that did not affect the weapons of the English longbowmen who responded with volleys of devastating arrow fire that decimated most of the incoming attackers. It was not too long thereafter that the remaining crossbowmen took flight, fleeing from their positions back towards the bulk of the French army.

Discipline Trumps Over Manpower

Displeased with the perceived cowardice of their fleeing units, the French Count of Alencon ordered the first wave of mounted knights to slay the retreating infantry as they advanced towards the ridge. This display of senseless brutality, however, only served to weaken their advance and the knights soon found themselves disorganized and struggling to ascend the ridge. All the while, the English longbowmen took advantage of the closing range and began pelting the approaching knights with deadly precision while their army’s organ guns administered lethal cannon fire that sent their enemy’s horses into a panicked frenzy. The small few who managed to make it to the top of the ridge within melee distance were quickly slaughtered by the dismounted English knights.

Illustration of the Battle of Crécy from an illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles (15th Century); Jean Froissart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration of the Battle of Crécy from an illuminated manuscript of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles (15th Century); Jean Froissart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite these poor attempts at breaking through the English line, the mounted knights of the French army continued to send charges in its direction with most of their attention being driven toward the right flank led by Edward of Woodstock also known as the Black Prince. The young prince’s line was even nearly overwhelmed by the French and he himself was nearly slain before besting the French and sending them packing back toward their line.

What ensued next was roughly 15 or more subsequent attacks from the French throughout the evening and into the night, all of which failed to avoid getting slaughtered by the English archers. The very few French soldiers who managed to get anywhere close to the English line were mowed down by the ferocious men-at-arms desperate to not afford their archers all the glory. At some point, Philip IV himself would join the battle and have more than just a single horse die beneath him. Eventually, after losing many men and gaining no ground from the English, the French king was reluctantly forced to call a retreat.

Aftermath

The French king and his army fled to a nearby chateau while Edward III and his men slept atop their unconquerable ridge. In total, they had only lost fewer than 100 soldiers. The French, however, were not nearly so lucky, having lost more than 10000 men, roughly 1500 of whom were knights and lords of the nobility. The toll on the English army was nevertheless too great to encourage any sort of push to chase down Philip IV’s severely crippled forces.

Not wanting to forego any opportunities his victory had assured him, however, King Edward III rode his army to the port city of Calais after some rest. He would put the city under siege and win its capitulation on the 3rd of August, 1347. This was a staggering loss for the French who would not reclaim it from English control until 1558.

In sum, the Battle of Crécy was another momentous footnote in the history of the medieval Hundred Years’ War. Much like the Battle of Agincourt, which would transpire several decades later, the English displayed the superior efficacy of solid tactics over unit strength, as well as the significant advantage of their longbows.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Won the Battle of Crécy?

The English who won the Battle of Crécy despite the immense numerical advantage of their French adversary. On the 26th of August 1346, Edward III’s English army of roughly 10000 men defeated a French army of nearly 30000 French soldiers near the town of Crécy in France.

When Was the Battle of Crécy?

The battle occurred on the 26th of August 1346. King Edward III’s invading army of approximately 10000 English soldiers would defeat King Philip IV’s army of roughly 30000 men, despite their numerical disadvantage.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.