Babylonian Art – Exploring the Art of Ancient Mesopotamia

Of all the ancient cities, Babylon (2300 BCE – c. 1000 CE) is believed to have been one the most beautiful according to legend, and is one of the most famous in antiquity. The city was renowned for its flourishing palaces and courtyards, and although nothing remains of the mythical Hanging Gardens, many Babylon artifacts and art have survived. In the below article, we take a brief look at the history of Babylon, the various types of beautiful art created there, and some of Babylonia’s most famous artworks and artifacts.

Where Was Ancient Babylon?

The ancient city of Babylon is located in southern Mesopotamia (where Iraq is today) close to the lower Euphrates river. From the early second millennium BCE to the early first millennium BCE, it was the capital of southern Mesopotamia, which was also known as Babylonia. In the seventh and sixth centuries BCE, it became the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, and this is when it reached its magnificent peak. Babylon’s ruins can be found near the present-day town of Al-Ḥillah in Iraq, about 55 miles away from Baghdad.

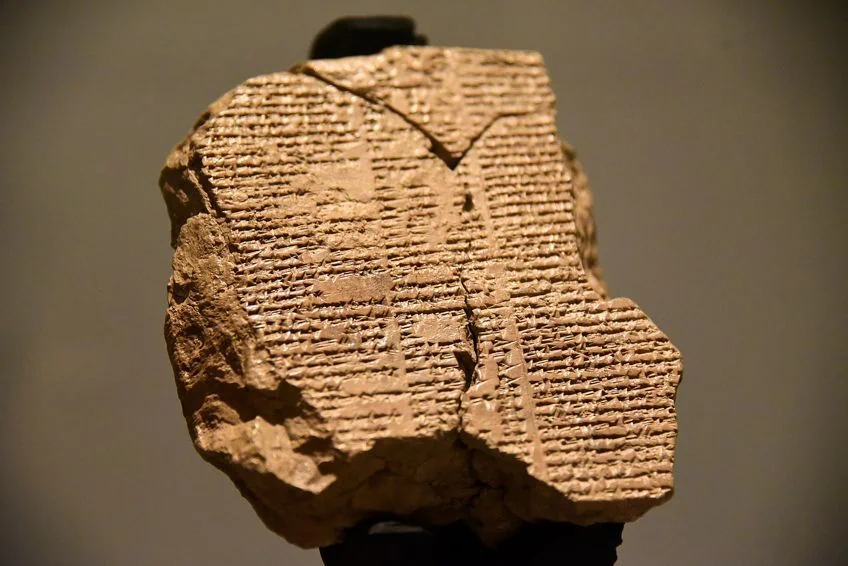

Tablet V of the Epic of Gilgamesh (2003 – 1595 BC); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tablet V of the Epic of Gilgamesh (2003 – 1595 BC); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Summary of the History of Babylon

The history of Babylon, like many ancient cultures, is long and for the purpose of this article, we will give you a bitesize version to put Babylon art into context. The was initially founded as a small port more than 4,000 years ago. The region of Babylonia covered the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and when the first line of Amorite kings took power after 2000 BCE, it was divided into Sumer, in the southwest, and Akkad, in the northwest. Under the rule of Hammurabi (c. 1810 – 1750), Babylon became one of the most dominant cities. After he died, Babylonia declined and people from the east, called the Kassites assumed power in about 1595 BCE. They set up a dynasty that would last about four centuries.

A new Babylonian dynasty was later established following a string of wars that took place after the Elam people conquered the region in 1157 BCE.

Part of this dynasty was Nebuchadrezzar I (c. 1127 – 1104 BCE) who ruled until c. 1104 BCE. A three-way struggle followed between Aram, Assyria, and Chaldea who wanted control of Babylonia, of which the most frequent ruler from the ninth to the seventh century was Assyria. The last and greatest period of Babybolian supremacy took place from the seventh to the sixth century under the rule of the Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar II (c. 642 – 562 BCE). During the Neo-Babylonian Empire, Palestine and Syria were conquered, and the capital city of Babylon was rebuilt.

Nayarit sculpture (250-500); José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Nayarit sculpture (250-500); José Luis Filpo Cabana, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This empire stretched from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean sea, and after defeating the Assyrians in 612 BCE at Nineveh, became the most powerful state in the ancient world. The Near East saw a cultural renaissance during this period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, with magnificent buildings and statues being produced and preserved. However, the Neo-Babylonian Empire did not last long, and in 539 BCE Babylon was conquered by Cyrus the Great (c. 600 – 530 BCE), a famous Persian king. The empire fell and came under the control of the Persians and was later conquered by Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, after which it was slowly abandoned.

Babylonian Advancements

The civilization of Babylon was very advanced for its time and made significant contributions like developing basic medical procedures such as prognosis, and cataloging an extensive range of symptoms and illnesses. They also produced astronomical record compendiums. These included ways for calculating various astronomical events and co-ordinates, as well as cataloged constellations of stars. As we will see below, the earliest and most complete legal code was created in Babylonia, which would later impact the entire world.

The opportunity to learn to read and write was given to both men and women, the bulk of literature being based on Sumerian works that were translated.

What Is Babylonian Art?

Babylonian art is art that was created in Babylonia by the inhabitants that lived there. Greatly influenced by the Sumerians and Akkadians that came before them, the Babylonian art form is known for its use of stylized forms, intricate details, and vibrant colors. Inlay, glazing, and relief were among the many techniques artists used to produce their work. Clay was initially used for many works due to the material being abundant and close by, then harder materials such as diorite or metals were used. The Babylonians produced ceramics, sculpture, jewelry, and ziggurats, which were architectural and religious structures in the shape of stepped temple pyramids that were built in most major cities of Mesopotamia.

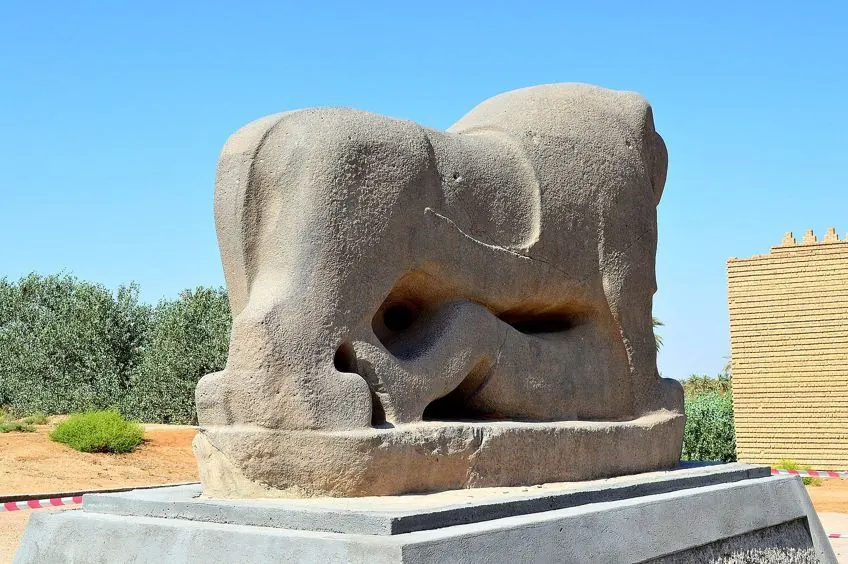

The Lion of Babylon Statue at the ancient city of Babylon, Mesopotamia, Iraq (6th Century BC); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Lion of Babylon Statue at the ancient city of Babylon, Mesopotamia, Iraq (6th Century BC); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Babylonian Ceramics and Pottery

During the Neo-Babylonian period, under King Nebuchadnezzar II, Babylon became a city full of color and splendor. A big part of this was the molded glazed bricks that decorated the gates and buildings of the city, depicting relief animals and figures in yellow, black, blue, red, and white. Although the reason for using these bricks was because stone is hard to find in southern Mesopotamia, the effect that they had was spectacular. Pottery in ancient Babylon was mostly made of clay and was embellished with motifs from everyday life, such as hunting or farming.

Items found in the households, such as seal cylinders (that were used for stamping images onto clay tablets) and vases were also artistically decorated with animal or human forms.

Babylon Paintings

Frescoes were prominent during the Old Babylonian period, as well as enameled tiles, which were often religious in subject matter. Elaborate works of art decorated the ziggurat temple walls, with some examples of the subject matter showing desires for fertility or good harvest. Although the use of perspective was still quite basic, and figures and surrounding objects were not realistically in proportion to one another, Babylon paintings, as with other forms of art, give us an idea of what was important to Babylonian culture. How figures are depicted in ancient paintings can indicate their importance. For example, figures of significance were often enlarged while the rest of the figures were smaller in size, depending on their status. The king would therefore be the largest in a group depicted, followed in size by other authoritative figures of secondary importance, and the remaining figures would be smaller.

Fresco of the investiture of Zimri Lim (19th century BC); Louvre Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR, via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco of the investiture of Zimri Lim (19th century BC); Louvre Museum, CC BY-SA 2.0 FR, via Wikimedia Commons

Popular painting subjects for Babylonian artists were scenes of combat, mythological figures, inaugurations, offerings, and sacrifices. Similar to Sumerian and other Mesopotamian cultures, faces of figures were depicted in profile. That is, facing to the side, even if the figure is technically facing the viewer. Their eyes were large and defined and their expression emotionless. Artists paid attention to details such as beards, long curly hair, embroidery on clothing, and hems on garments.

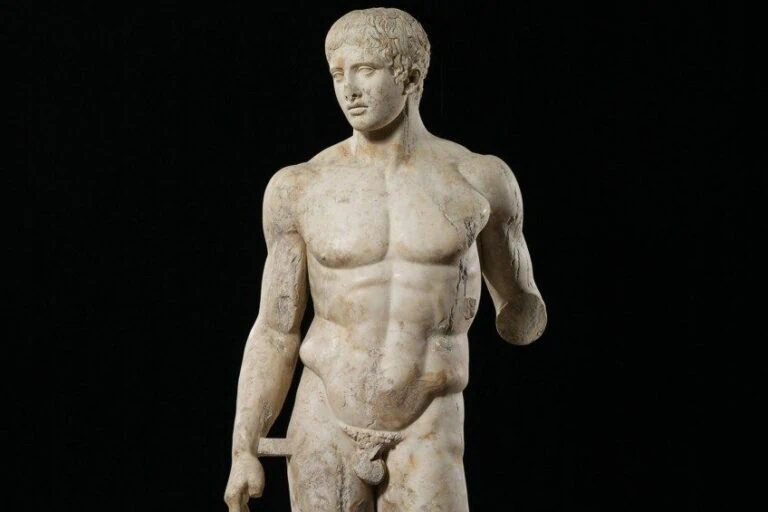

Babylonian Statues and Sculpture

Most Babylonian statues and sculptures were made of terracotta or stone, and figures were presented with exaggerated features and stylized eyes that were quite large. Free-standing statuary were produced which were quite realistic and three-dimensional. Because stone was rare, it was valuable to the artists of Babylon and they became expert stone carvers and cutters. Sculptures were placed in significant sites, like temples, due to their religious and symbolic importance. Large figures could be found near the entrances to the palace, serving as protectors of the property.

Often enormous in size, these figures were part human and part animal, fusing human features with winged sphinxes, griffins, and lions, also seen in Sumer and Assyria.

Famous Babylon Artworks and Babylon Artifacts

The city of Babylon was a melting pot of cultures, being ruled by different groups over the years. For centuries, Babylon’s art was influential, as the city was seen as a cultural center of the ancient world. It also influenced their rulers’ art, especially that of the Assyrians. Below, we have listed a few of the most famous Babylonian artworks and artifacts.

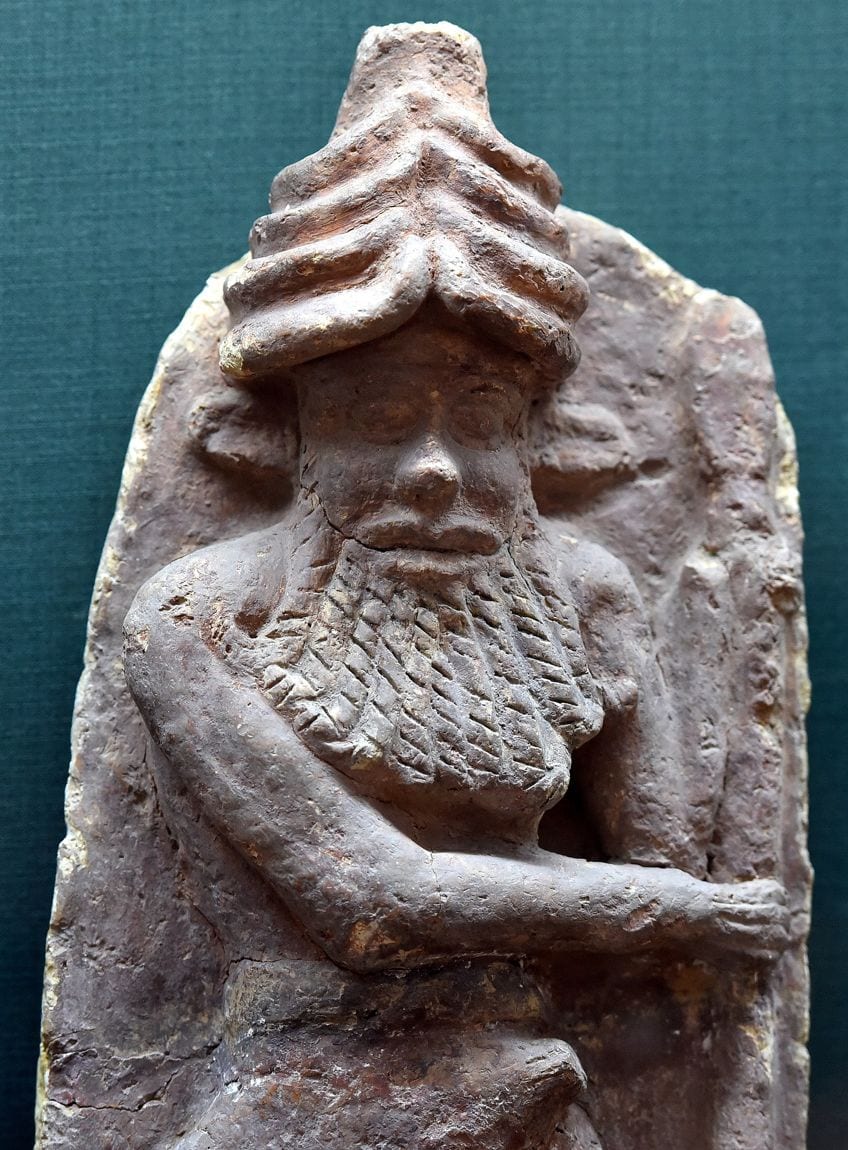

Terracotta wall panel depicting Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s friend (2027-1763 BC); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Terracotta wall panel depicting Enkidu, Gilgamesh’s friend (2027-1763 BC); Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

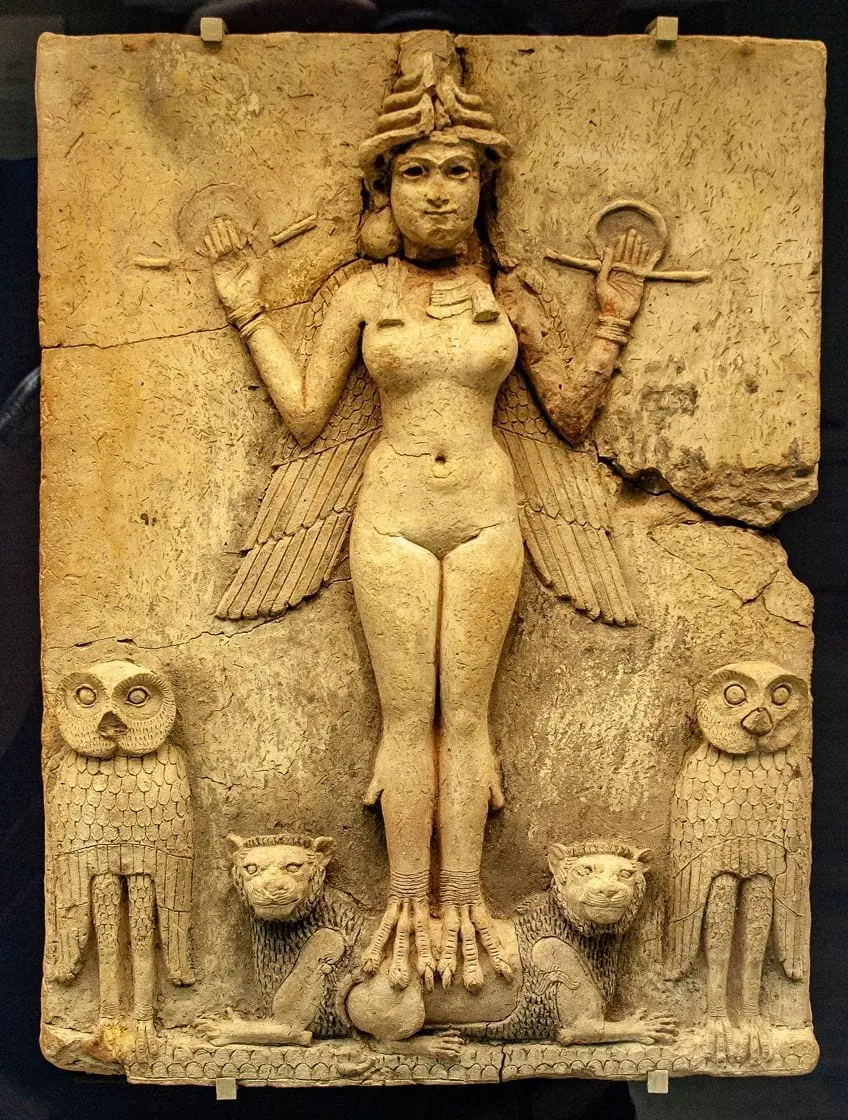

The Queen of the Night (c. 1800 – 1750 BCE)

| Artwork Title | The Queen of the Night |

| Artist | Old Babylonian artists |

| Date | c. 1800 – 1750 BCE |

| Medium | Clay relief sculpture |

| Dimensions (cm) | 39 x 37 |

| Current Location | British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

This Old Babylonian high-relief sculpture of the Queen of the Night (c. 1800 – 1750 BCE) is made from baked straw-tempered clay. Originally painted red, the goddess holds a rod and ring, symbols of justice, while her long wings hang down, further indicating her position as a goddess of the Underworld. Her headdress has horns, which is typical of a Mesopotamian deity, and her feet are bird’s talons. Her association with the night was further indicated by the backdrop originally being painted black. She is flanked by two large owls, while she stands on the backs of two smaller lions. The figure could represent aspects of a few goddesses; Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, or perhaps her sister, Ereshkigal who ruled the Underworld and was also her rival. She may even be Lilitu or Lilith, as known in the Bible, the demoness.

The work was likely originally contained in a shrine. The goddess also appears on basic, small, mold-made plaques from about 1750 BCE. The Queen of the Night has also come to be known as the Burney Relief since it was shown in the Illustrated London News in 1936, titled after its owner at the time. Until 2003, it was privately owned.

The Queen of the Night (c. 1800 BCE); British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Queen of the Night (c. 1800 BCE); British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Code of Hammurabi (1792 – 1750 BCE)

| Artwork Title | The Code of Hammurabi |

| Artist | Hammurabi (c. 1810 – 1750) and Babylonian artists |

| Date | 1792 – 1750 BCE |

| Medium | Basalt stele |

| Dimensions (cm) | Height: 225, and circumference: 190 at the base to 165 at the top |

| Current Location | The Louvre, Paris, France |

This artifact is important in Babybolian art history as it was created by Hammurabi, one of Mesopotamia’s most powerful leaders. Most significant is that it is the earliest and most complete legal code, consisting of a list of 282 laws and penalties inscribed onto the stele. The laws of the whole world would later be influenced by this legal code. “An eye for an eye” may be recognizable to you; it was one of the laws included on the stele. A stele is a ceremonial or memorial column, and the Code of Hammurabi combines art, literature, and law in one.

At the top of the stele is a relief sculpture depicting Hammurabi standing in front of a very important god, Shamash, from whom he is receiving the laws.

Stele of Hammurabi (1793 – 1751 BC); Hammurabi, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Stele of Hammurabi (1793 – 1751 BC); Hammurabi, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Cuneiform Cylinder (c. 604 – 562 BCE)

| Artwork Title | Cuneiform Cylinder: inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II describing the construction of the outer city wall of Babylon |

| Artist | Neo-Babylonian artists |

| Date | c. 604 – 562 BCE |

| Medium | Clay |

| Dimensions (cm) | 6.7 x 12.35 x 7.2 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

Cuneiform cylinders were part of a long established Mesopotamian tradition; made of clay and inscribed in cuneiform, they were buried within the buildings’ foundations that were being restored or built. Often cylinders record the restorations of ancient buildings, but the cylinder featured here commemorates Nebuchadnezzar’s building program in Babylon and describes the construction of the outer city wall. The text inscribed onto clay cylinders were mainly meant to be seen by the gods, but it was also hoped that they would be discovered by future kings who were carrying out their own restorations, and therefore, honor and keep the name of the builder alive. In this regard, Nebuchadnezzar II ensured to perpetuate his name by including it not only on cylinders, but also on baked bricks, and inscribed on large stones.

The top surface of the bricks were stamped, so that they would be hidden from the eyes of people, much like the cylinders, but their inscriptions are still there, repeated millions of times throughout the bricks of the city walls and the king’s palace.

Cuneiform cylinder: inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II describing the construction of the outer city wall of Babylon (604–562 B.C.); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Cuneiform cylinder: inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II describing the construction of the outer city wall of Babylon (604–562 B.C.); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Panel with Striding Lion (c. 604 – 562 BCE)

| Artwork Title | Panel with Striding Lion |

| Artist | Babylonian artists |

| Date | C. 604 – 562 BCE |

| Medium | Glazed ceramic |

| Dimensions (cm) | 97.2 x 227.3 |

| Current Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

This Panel with Striding Lion (c. 604 – 562 BCE) is found north of the Ishtar Gate, through which the Processions Way (an important street in the city of Babylon) leads to the Bit Akitu, or the “House of the New Year’s Festival”. On this side of the gate, glazed striding lions lined the roadway. The lion is associated with the goddess of love and war, Ishtar, and these figures were meant to protect the street.

Ritual processions took place from the city to the temple, and the repeated design of the lion on the walls served as a guide leading the way.

Processional Way, Babylon (604 BCE – 562 BC); Pergamon Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Processional Way, Babylon (604 BCE – 562 BC); Pergamon Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Ishtar Gate (575 BCE)

| Artwork Title | The Ishtar Gate |

| Artists | Nebuchadnezzar II (c. 642 – 562 BCE) and Babylonian artists |

| Date | 575 BCE |

| Medium | Glazed ceramic |

| Dimensions (cm) | 1,400 x 1,500 |

| Current Location | On site in Babylon, Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq |

The Babylonian King, Nebuchadnezzar II built the Ishtar Gate (575 BCE), and the structure was decorated with symbols of the deities, Marduk and Adad, as well as dragons and bulls. This was the city’s eighth gate and served as the major entry point into Babylon. It was part of Nebuchadnezzar’s plan to upgrade and enhance the capital of the empire. In this attempt he also renovated Marduk’s temple and, according to legend, erected the Hanging Gardens. Unfortunately, there has not been a lot of evidence proving that The Hanging Gardens, which was regarded as one of the Seven Wonders of the World, actually existed in Babylon.

Research has suggested that perhaps the location was mixed up with Nineveh, which was situated in Upper Mesopotamia.

Ishtar Gate (575 BCE); David Stanley, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ishtar Gate (575 BCE); David Stanley, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Ishtar Gate was named after the goddess of love, sexuality, fertility, and war, although several other deities are honored along its walls. Each animal depicted is connected with a certain deity; the bulls are associated with Adad, the god of weather, while the dragons are associated with the supreme god, Marduk, and the lions with Ishtar. On the front of the gate, the yellow and brown dragons and bulls are depicted in alternate rows and contrast against the dark blue brickwork. This gives a neat, symmetrical appearance to the structure. It is still debated whether lapis lazuli was the medium used to make the beautiful blue enameled tiles.

That rounds up our article on Babylonian art and Babylonian artifacts. We hope that you enjoyed learning about this ancient art and culture just as much as we did, and that it inspired you to further your exploration into the history of ancient art!

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Was Babylon?

The ancient city of Babylon is located in southern Mesopotamia (where Iraq is today), close to the lower Euphrates river. Its ruins can be found near the present-day town of Al-Ḥillah in Iraq, about 55 miles away from Baghdad.

What Is Babylonian Art?

Babylonian art is art that was created in Babylon, an ancient city situated in what is known today as Iraq. Clay was initially used due to the material being close by and in abundance, however, harder materials such as diorite or metals were used after. The Babylonians produced ceramics, sculpture, jewelry, and ziggurats, which are architectural and religious structures in the shape of a stepped temple pyramid.

How Did the Ancient City of Babylon Come to an End?

Less than one hundred years after the Neo-Babylonian Empire was founded, it came to an end in 539 BCE when Babylon was conquered by Cyrus the Great (c. 600 – 530 BCE), a famous Persian king. The empire subsequently fell and came under the control of the Persians.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.