Famous Roman Statues – Early to Late Period Roman Sculpture

The famous Roman sculptures that its citizens left behind serve as a record of the Roman Empire’s history, which spanned many centuries and several continents. The ancient Romans coupled previously unfathomable military prowess with a similarly zealous dedication to public artworks such as the male and female Roman statues, which functioned as both propaganda and a method of commemorating diplomatic and military achievements. Yet, many Roman sculpture characteristics can be attributed to the Greeks who came before them and who had a significant impact on ancient Roman sculptures. To gain a better understanding of Roman sculpture, we will be looking at a list of the most famous Roman statues from antiquity.

Contents

- 1 Famous Roman Statues

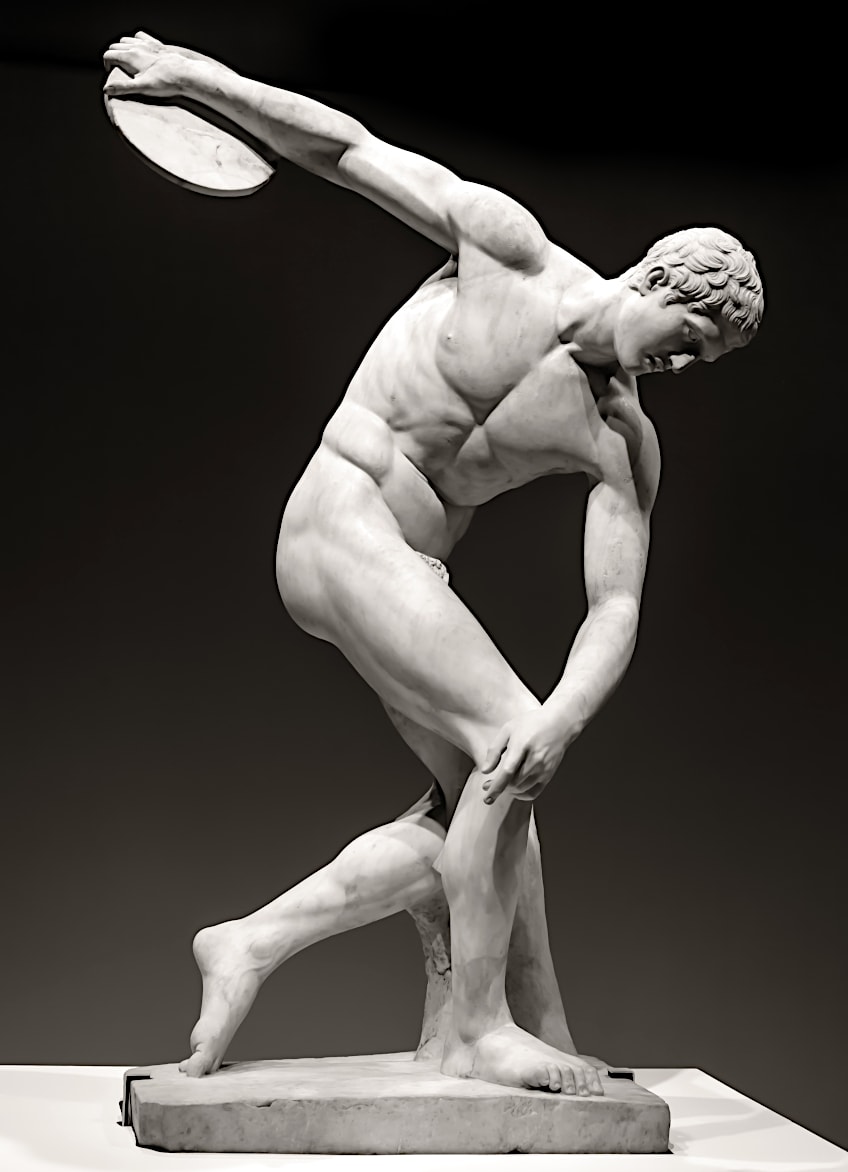

- 1.1 The Discus Thrower (460 BCE)

- 1.2 Hercules of the Forum Boarium (2nd century BCE)

- 1.3 Tusculum Portrait (c. 50 BCE)

- 1.4 The Orator (1st Century BCE)

- 1.5 Head of a Roman Patrician (c. 1st Century BCE)

- 1.6 The Mouth of Truth (1st Century CE)

- 1.7 The Colossal Head of Augustus (1st Century CE)

- 1.8 Augustus from Prima Porta (1st Century CE)

- 1.9 Apollo Belvedere (c. 124 CE)

- 1.10 Fonseca Bust (2nd Century CE)

- 1.11 The Belvedere Torso (c. 2nd century CE)

- 1.12 Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (176 CE)

- 1.13 Farnese Hercules (c. 216 CE)

- 1.14 Sarcophagus of Saint Helena (4th Century CE)

- 2 Frequently Asked Questions

Famous Roman Statues

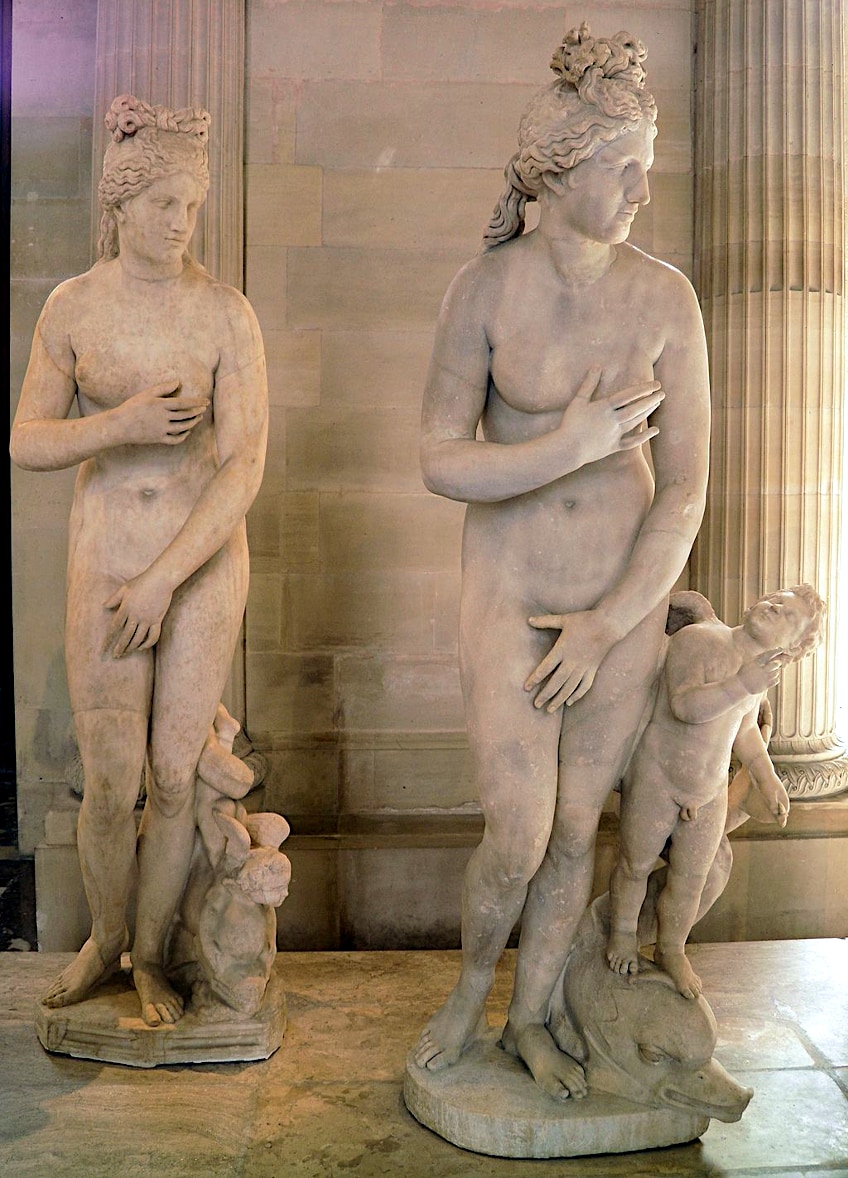

Even though the Romans defeated the Greeks at the Battle of Corinth in 146 BCE, cultural submission by the Greeks was not a required aspect of military victory. Instead, affluent Romans paid for copies of well-known marble statues created by gifted Greek craftsmen like Praxiteles. The majority of Roman sculptors, meanwhile, never achieved such fame. Because of the artisans’ poor social status and the widespread Roman preference for Greek masterworks, their copies were typically left unsigned. Many of ancient Greece’s greatest sculptures that are known from textual evidence would have been lost to history were it not for this flourishing trade in Roman copies.

Roman sculpture of Capitoline Venus as based on the Greek sculpture of Aphrodite of Cnidus (2nd Century CE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman sculpture of Capitoline Venus as based on the Greek sculpture of Aphrodite of Cnidus (2nd Century CE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

One area where Roman sculptors excelled was portraiture. Romans venerated their ancestors by displaying sculpture of them in their homes, and even carried these busts during certain religious processions. By raising portraiture to previously unheard-of degrees of verism and sponsoring enormous public works projects that represented intricate mythology and military triumphs, the Romans made their mark on sculpture.

Examples showing the stylistic range of Roman portrait sculpture

Examples showing the stylistic range of Roman portrait sculpture

Roman leaders used Roman sculptures as propaganda starting with the first emperor, Augustus. These sculptures, which were often made of bronze or marble, exalted their figures and emphasized (sometimes fictional) connections to illustrious military heroes in history. There are several surviving ancient Roman sculptures and artifacts from the Roman era.

Bronze statue of Emperor Nero in Anzio, Rome

Bronze statue of Emperor Nero in Anzio, Rome

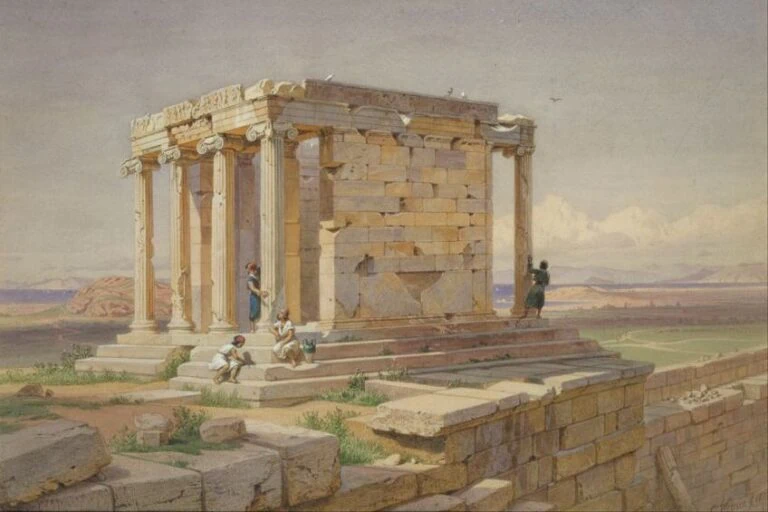

The Discus Thrower (460 BCE)

| Artist | Myron (c. 5th century BCE) |

| Date | 460 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (m) | 1.7 |

| Location | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

The Discus-Thrower from Hadrian’s Villa (2nd Century CE). The head has been incorrectly restored and should look back at the discus instead of downwards

The Discus-Thrower from Hadrian’s Villa (2nd Century CE). The head has been incorrectly restored and should look back at the discus instead of downwards

This statue is a Roman reproduction of a Greek original. According to historical chronology, the Greeks were already contemplating the purpose of life whereas the Romans were still existing as lowly peasant farmers. As the Romans gradually caught up to the Greeks in terms of civilization, they “borrowed” from them by simply copying their statues. The athlete is focused as he twists his body in order to throw the discus. The statue’s shape is completely symmetrical and looks to be life-like. The most famous copy of this statue was discovered amid the ruins of Hadrian’s Villa, around 45 minutes from Rome.

Hadrian, who adored all things Greek, ordered hundreds of reproductions of authentic Greek sculptures.

Hercules of the Forum Boarium (2nd century BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (2nd century BCE) |

| Date | 1st century BCE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Height (m) | 2.41 |

| Location | Capitoline Hill, Rome, Italy |

Hercules of the Forum Boarium (2nd Century BCE); Capitoline Museums, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hercules of the Forum Boarium (2nd Century BCE); Capitoline Museums, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The bronze Roman sculpture is somewhat larger than life size and was created in the Hellenistic manner of the 2nd century BCE. The Hellenistic aesthetic was founded on Lysippos’ canon of proportions, which he created in the early 4th century BCE. The sculpture’s muscles are accentuated, and the head is proportionately smaller than the rest of the body. The Forum Boarium sculpture is one of only two full-sized Greek sculptures from ancient Greece that have survived. The Hercules statue from the Forum Boarium is based on his 12 labors in which he must return the Golden Apples of Hesperides to Eurystheus. During his hunt, Hercules came across Prometheus and liberated him from his cage. In exchange, Prometheus revealed the location of the Golden Apples.

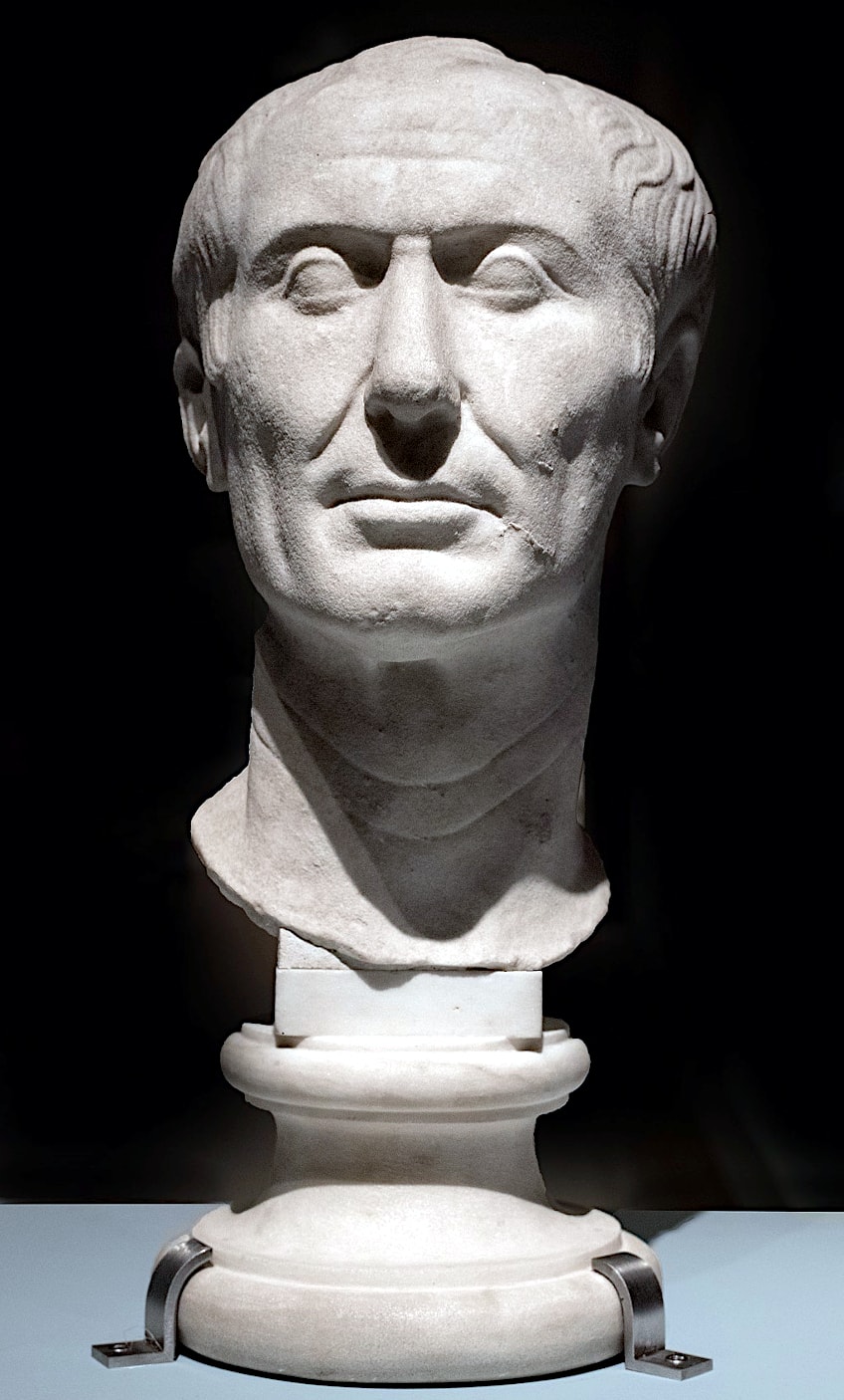

Tusculum Portrait (c. 50 BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 50 BCE) |

| Date | c. 50 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (cm) | 33 |

| Location | Museum of Antiquities, Turin, Italy |

The Tusculum portrait is the only known portrait of Julius Caesar that was created during his lifetime. It also serves as one of the two acknowledged portraits of Caesar produced prior to the establishment of the Roman Empire. The Roman bust sculpture, which is one of the replicas of the bronze original, dates to circa 50 BCE. The portrait’s facial traits match those found on coins produced just before Caesar’s death, notably on Marcus Mettius’ denarii.

Tusculum Portrait (c. 50 BCE); Museum of antiquities, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tusculum Portrait (c. 50 BCE); Museum of antiquities, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The bust’s head is extended, producing a saddle-like shape, which might be the consequence of early ossification of the ridges between Caesar’s temporal and parietal bones. The depiction, like the Arles bust, features a wrinkly neck, which might have resulted from years of campaigning in harsh weather; this characteristic has been deleted from other posthumous portraits but can be observed on at least one coin produced during Caesar’s reign.

The Orator (1st Century BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century BCE) |

| Date | c. 1st century BCE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Height (cm) | 179 |

| Location | National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy |

A draped adult male stands with his right arm extended in the life-size Roman statue. The figure is in a frontal position with a minor contrapposto stance. According to the plaque on the sculpture, the person is Aulus Metellus. He is undoubtedly a magistrate, and his stance appears to be that of an orator about to speak to the public. He is dressed in a tunic with a toga thrown over it – the magistrate’s ceremonial apparel. The toga is draped around the torso, but the right arm is exposed. His feet are dressed in the high boots that Roman senators wore. His face and slightly wide mouth endear him to the viewer. The town initially constructed the sculpture in commemoration of Aulus Metellus.

The Orator (1st Century BCE); Sailko, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Orator (1st Century BCE); Sailko, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The statue provides a glimpse of the shifting socio-political environment of the Italian peninsula during the second half of the first millennium BCE – a period when sweeping change brought about by Rome’s authoritarian successes and flourishing population signaled a significant and enduring change for other Italian peoples, along with the Etruscans.

During the 5th to the 1st century BCE, as Rome’s territory extended, her neighbors were progressively drawn into the realm of Roman intellectual, cultural, and political power. Of course, some communities resisted in some fashion, while others eagerly joined up through military and political accords, as well as by embracing a Roman lifestyle.

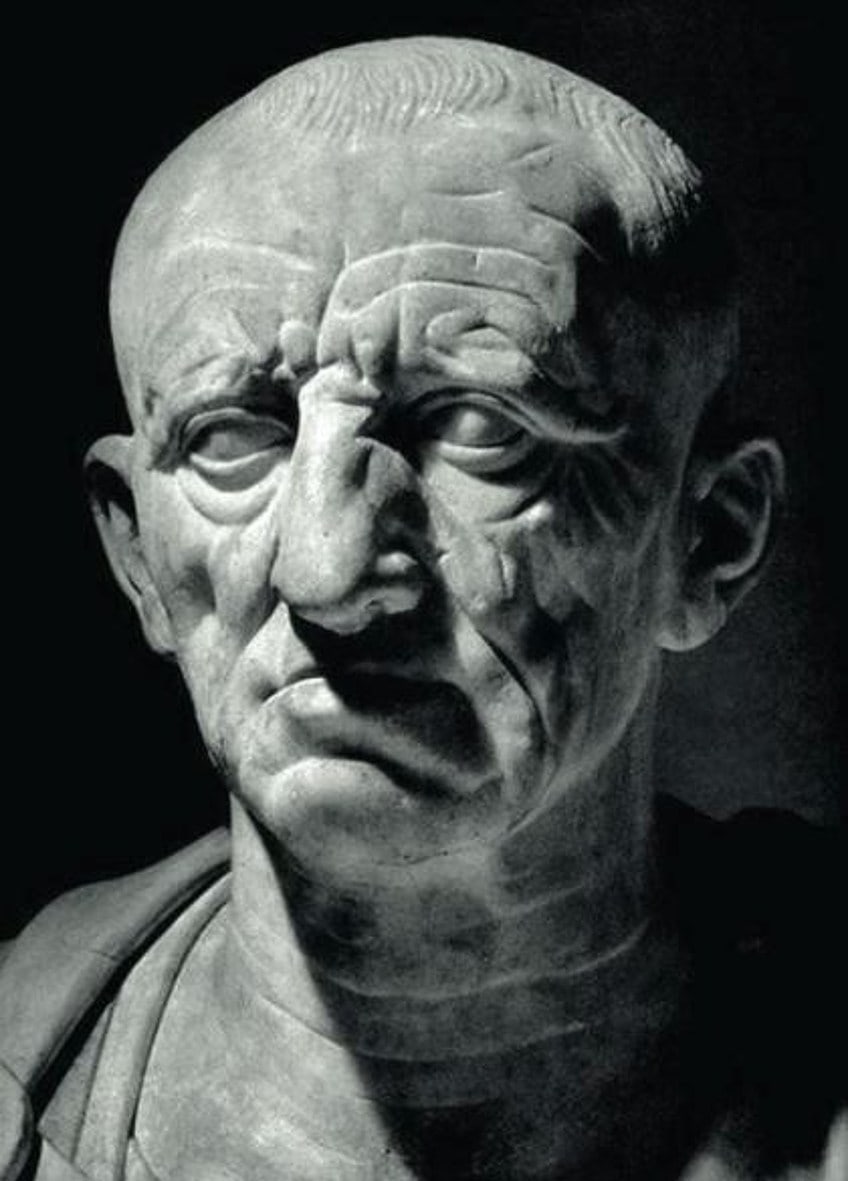

Head of a Roman Patrician (c. 1st Century BCE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century BCE) |

| Date | c. 1st century BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (cm) | 35 |

| Location | Palazzo Torlonia, Rome, Italy |

The wrinkled, old face of this anonymous upper-class Roman citizen embodies the principles of the Roman Republic, which valued service to the public and the military power of their country above all else. Instead of just replicating Greek marble sculptures by producing idealized depictions of their rulers as heroes, Roman Republic citizens aspired to exhibit their principles in human form. To that purpose, this bust avoids portraying the subject as a youthful, athletic man, instead emphasizing his maturity level hence wisdom – through the significant wrinkles etched into his neck and face. The 1st century BCE bust also references the politics of the time: the early Roman Republic was controlled solely by patricians.

Head of a Roman Patrician (c. 1st Century BCE); scan from 19th century book, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Head of a Roman Patrician (c. 1st Century BCE); scan from 19th century book, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This Roman bust sculpture is a great example of verism. Verism is a type of hyperrealism in sculpting in which the subject’s naturally occurring qualities are amplified, frequently to the point of ridiculousness. In the instance of public Roman bust sculpture, middle-aged men develop veristic inclinations to the point where they seem excessively elderly and careworn.

This artistic inclination is informed by both the tradition of ancestral images and a great love for family, tradition, and genealogy. The images were basically death masks of important ancestors that the family retained and showed.

The Mouth of Truth (1st Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century CE) |

| Date | c. 1st century CE |

| Medium | Stone |

| Diameter (m) | 1.7 |

| Location | Piazza della Bocca della Verità, Rome, Italy |

Long before the sophisticated lie detector with its jittering charts and cables, the deceitful individuals of antiquity faced a much more horrible destiny between the teeth of the Mouth of Truth, an ancient sculpture reputed to bite liars’ hands off. While no one knows for certain when or why the frieze was produced, there are several ideas. The Roman sculpture, which dates from approximately the 1st century CE, is a towering stone disc fashioned into a human-like face with hollowed holes for eyes and an open mouth. The big medallion’s intended function has been speculated to be anything from a traditional well cover to a component of fountain adornment to a manhole cover.

The Mouth of Truth (1st Century CE); Fallaner, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Mouth of Truth (1st Century CE); Fallaner, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The visage itself has been claimed to depict a pagan god, although which one is unknown, with researchers speculating on everything from the woodland god Faunus to the sea god Oceanus to a native river god.

The Colossal Head of Augustus (1st Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (1st century CE) |

| Date | 1st century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (cm) | 250 |

| Location | Vatican Museum, Vatican City, Italy |

Ennio Quirino Visconti identified the massive marble head, known since the XVI century, as the giant visage of Emperor Augustus towards the end of the XVIII century. The identification of the old statue has sparked several debates. Given the scale of the head, it must have been constructed from multiple individually wrought parts and must have reached a height of 10 meters. Literary texts and imperial coins both mention colossal pictures of the first emperor constructed after his death in 14 CE. Historians recall in particular the sculpture constructed in the Forum of Augustus.

The Colossal Head of Augustus (1st Century CE); Alvesgaspar, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Colossal Head of Augustus (1st Century CE); Alvesgaspar, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It is difficult to definitively state which edifice in ancient Rome contained the massive artwork. Only the head survived, a testimony to Augustus’ most enormous image, which immortalized the Emperor in the hieratic attitude of a deity.

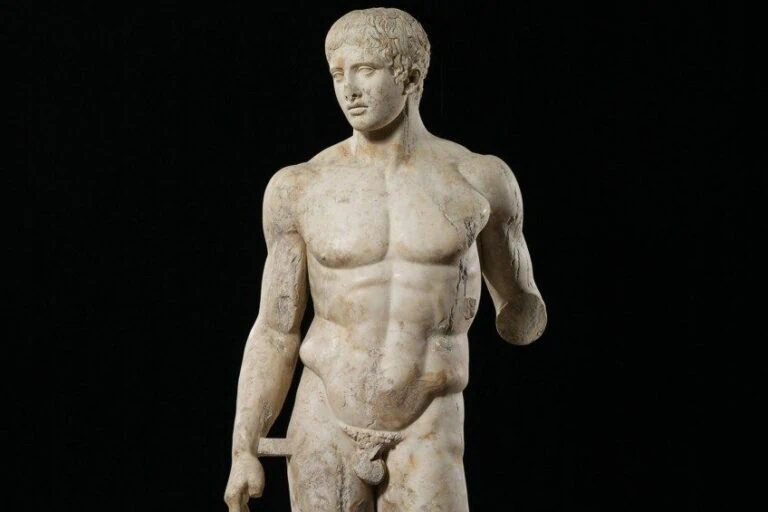

Augustus from Prima Porta (1st Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century CE) |

| Date | c. 1st century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (m) | 2,08 |

| Location | Musei Vatican, Rome, Italy |

Rigid verism is ignored here, and Augustus is shown as an idealized person, with an athletic physique resembling a classical Greek statue rather than a genuine Roman ruler. His body and head are reminiscent of the spear-bearer figure by the Greek sculptor Polykeitos from the 5th century BCE. The strands of hair that Augustus’ official painters always included made all sculptures of the emperor recognizable by the Roman populace.

Augustus of Prima Porta (1st Century CE); Vatican Museums, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Augustus of Prima Porta (1st Century CE); Vatican Museums, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It celebrates Augustus’ combat abilities and makes reference to the Republic’s former heyday, which he declared to have brought back under his authority. Augustus’ breastplate exhibits a particular diplomatic success that displays his aspirations: It shows a Parthian king reinstating military insignia that had been used by Roman forces. Augustus’ right ankle is where Cupid emerges, affirming the emperor’s divine rights.

Apollo Belvedere (c. 124 CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 1st century CE) |

| Date | c. 124 CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (cm) | 224 |

| Location | Vatican Museum, Vatican City, Italy |

In 1508 the Apollo Belvedere arrived at the Vatican. Pope Julius II owned it before he became pope. As a result, like many previous popes, he transported all of his art with him to his new residence, the Vatican, upon rising to the position. The sun god Apollo has just released an arrow and is monitoring where it lands in the statue. This sculpture is a mid-2nd-century CE Roman replica of an ancient Greek bronze statue by Leochares from circa 320 BCE. The gorgeous haircut and flowing cape are period-appropriate touches.

Apollo Belvedere (c. 124 CE); After Leochares, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Apollo Belvedere (c. 124 CE); After Leochares, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This striking statue originally graced the Agora, Athens’ largest plaza, according to the Greek historian Pausanias.

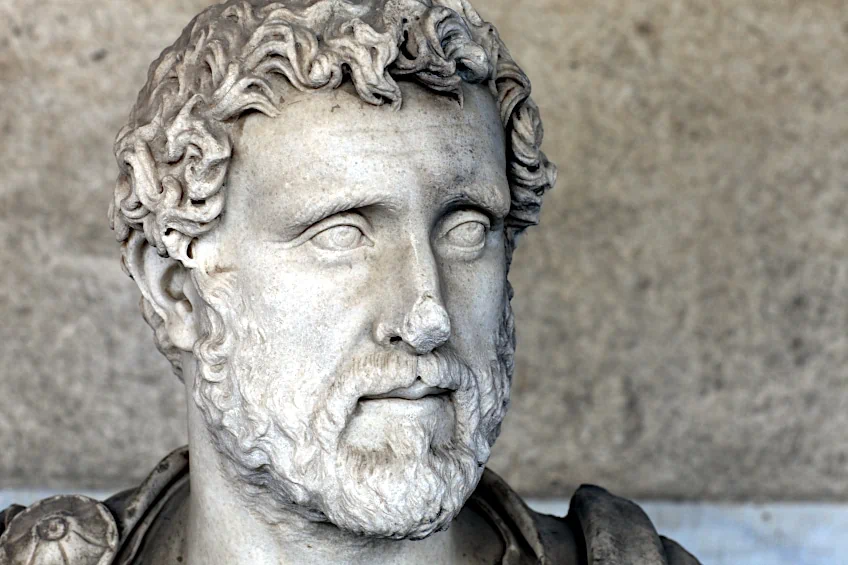

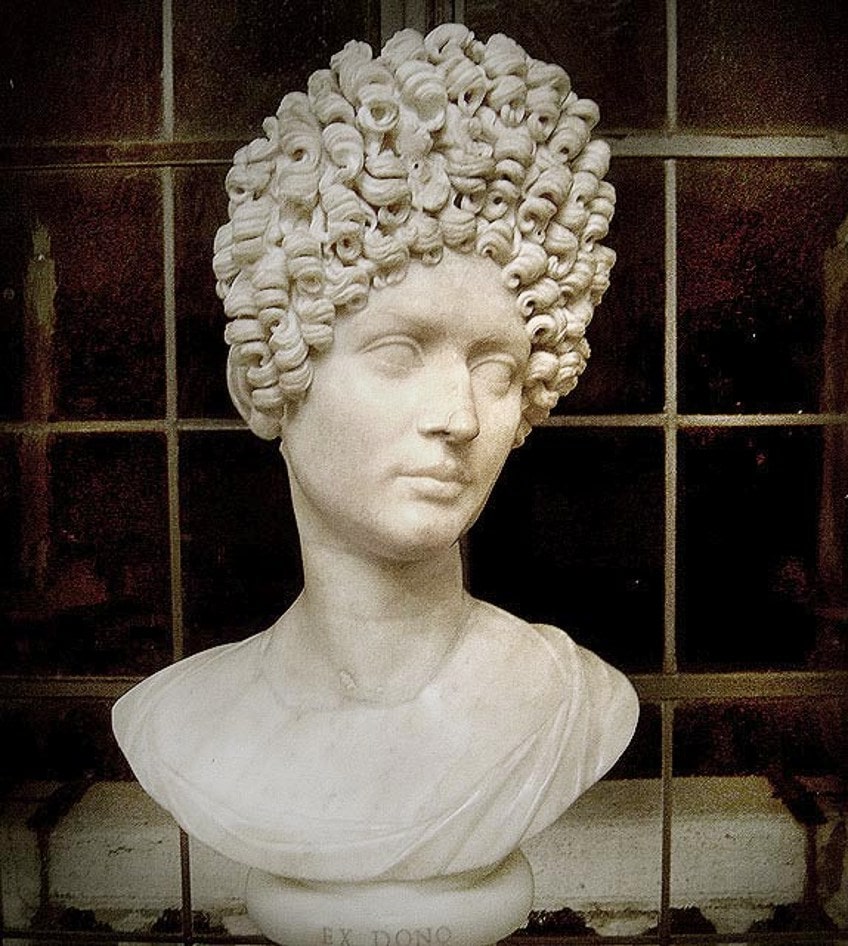

Fonseca Bust (2nd Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (c. 2nd century CE) |

| Date | c. 2nd century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (cm) | 160 |

| Location | Capitoline Museum, Rome, Italy |

Elite female Roman statues were much less lifelike compared to those of their male equivalents since they were meant to highlight feminine beauty and the newest fashions instead of providing accurate representations. This woman is the most fashionable on the list, and her piled-on curls give a glimpse at the Romans’ penchant for elaborate hairdos. Rich Roman women paid hairdressers to iron curl or sew extensions to their hair. The usage of extensions would have been absolutely necessary for this look.

Fonseca Bust (2nd Century CE); Tetraktys, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fonseca Bust (2nd Century CE); Tetraktys, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This Roman bust sculpture most likely depicts a female member of the Flavian dynasty. Male portraits from this time period tended to be realistic, yet this one is overdone to emphasize the sitter’s attractiveness. Many busts from this time period depict ladies with elaborately curled hair in the Marie Antoinette manner. Thanks to new advancements in drilling technology and aesthetic expertise, artists were able to create beautiful spirals.

The Belvedere Torso (c. 2nd century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (2nd century CE) |

| Date | 2nd century CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (m) | 1.59 |

| Location | Vatican Museum, Vatican City, Italy |

The Belvedere Torso (c. 2nd Century CE); Emiliovillegas24, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Belvedere Torso (c. 2nd Century CE); Emiliovillegas24, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Many people are taken aback when they come inside this chamber and discover only a torso. Why did the Vatican put a sculpture in the center of a room that had no hands, head, or feet? In modern days, we take for granted all of the materials available to help us learn anatomy. The brilliance of this statue is that his body is moving, contorting to the left, and all of his muscles perfectly complement that movement. This suggests that the sculptor was well-versed in anatomy. Even throughout the Renaissance era, it was illegal to dissect persons in order to study muscles and anatomy. The strong masculine figure is resting on an animal hide, and its specific identity is unknown.

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (176 CE)

| Artist | Unknown (176 CE) |

| Date | 176 CE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Height (m) | 4.24 |

| Location | Capitoline Hill, Rome, Italy |

This Roman sculpture is unmentioned in early literary sources, although it was most likely built around 176 CE, along with many other honors, to commemorate his victory over the Germanic peoples, or in 180 CE, not long after his passing. During the period, Rome had a great number of equestrian sculptures; late-Imperial inventories of the city’s districts included 22 such monuments, known as equi magni – larger-than-life statues, like the Marcus Aurelius monument.

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (176 CE); Capitoline Museums, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (176 CE); Capitoline Museums, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The monument, however, is the only one that has endured to the current day, and due to its integrity, it quickly came to represent all individuals who sought to claim ancestry from Imperial Rome. Its presence in the Lateran is first documented in the 10th century, but it is likely that it was there as early as the end of the 8th century when Charlemagne wanted to replicate the design of Campus Lateranensis when he relocated a comparable equestrian statue to his castle in Aachen from Ravenna.

Farnese Hercules (c. 216 CE)

| Artist | Glykon (c. 2nd century CE) |

| Date | c. 216 CE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Height (m) | 3.17 |

| Location | Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy |

Farnese Hercules (c. 216 CE); Naples National Archaeological Museum, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

The Farnese Hercules is an old statue, most likely an enlarged replica constructed in the early 3rd century CE and attributed to Glykon, who is otherwise unknown; his name is Greek, although he might have worked in Rome. It is a replica or reproduction of a much earlier Greek original that was widely known, in this instance a bronze by Lysippos constructed in the 4th century BCE, as are many other Ancient Roman sculptures. This original lasted nearly 1,500 years before being melted down by Crusaders at the Sack of Constantinople in 1205.

Sarcophagus of Saint Helena (4th Century CE)

| Artist | Unknown (4th century CE) |

| Date | 4th century CE |

| Medium | Porphyry Marble |

| Height (cm) | 242 |

| Location | Vatican Museum, Vatican City, Italy |

Sarcophagus of Saint Helena (4th Century CE); Dennis Jarvis from Halifax, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sarcophagus of Saint Helena (4th Century CE); Dennis Jarvis from Halifax, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Behind every great man, sits a special female. Frequently, such a lady is the mother. Helena, Emperor Constantine the Great’s mother, died in 335 CE. She was laid to rest at a tomb dedicated to her in Tor Pignattara, on the way to Casalina just outside Rome. The coffin seen above is composed of red porphyry, the hue designated for emperors. The military-themed embellishments would have been unusual for a woman’s tomb, leading experts to assume that the tomb was designed for a man, probably Constantine’s father or Constantine himself. Giovanni Pierantoni and Gaspare Sibilla took the sarcophagus from the outskirts of Rome in 1777 and refurbished it. The tomb was placed on four lions sculpted by Francesco Antonio Franzoni.

That wraps up our look at famous Roman sculptures. While many famous Roman statues were replicas of older Greek originals, that does not take anything away from the talent of the Roman sculptors. The combination of realism and idealism that marked Roman innovations in portraiture would prove highly influential in the Renaissance and Neo-Classical periods.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Were the Common Roman Sculpture Characteristics?

The idealized perfection of Classical Greek sculpture was combined with a stronger aim for realism in Roman art. It also absorbed Eastern aesthetic tastes and techniques to create images in stone and metal that rank among the best works of antiquity. Roman sculpture is exceptional for its variety, with artists working throughout a vast empire and ever-changing public preferences over centuries. Due to the Roman preference for Greek sculptures, when the original works were all utilized, duplicates had to be made. The quality of these replicas varies based on the talent of the sculptor. In fact, Pasiteles, together with Evander, Archesilaos, Glykon, and Apollonios, led a school in Rome and Athens dedicated to reproducing famous Greek originals. It was also common for many Roman artists to produce miniature reproductions of Greek originals, typically in bronze, which sculpture collectors collected and put on display in their homes.

What Were the Famous Roman Statues Made From?

The Romans, like the Greeks, produced statues with precious metals, stone, glass, and terracotta, but their finest work was in marble and bronze. Yet, because metal has always been in great demand for re-use, the majority of surviving Roman sculptures are in marble. The Roman sculptors were as devoted to creating sculptures of their deities as Greek ones were. When Roman rulers started to proclaim their divinity, they too became the topic of often gigantic and idealized sculptures. Often, the figure is shown with an arm lifted to the people and striking an intimidating pose.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.