Greek God Oceanus – Father of Life-Giving Waters

Greek mythology has its own unique ideas about how the world was laid out and how natural systems worked. One such idea is that the greatest river in the world was that which encircled the earth and was personified as the Greek god Oceanus. As the father of innumerable children and through them the fount of all water sources, Oceanus has had an interesting role in the myth and geography of the ancient Greek world. Come join us as we find out more about this Titan in the article below.

Oceanus: The Great River Around the World

| Name | Oceanus or Ogenos |

| Gender | Male |

| God of | The river Oceanus, and the source of all waters |

| Personality | Benevolent and passive |

| Symbols | Serpent and fish |

| Consorts | Tethys |

| Children | The Potamoi, the Oceanids, and the Nephelai |

| Parents | Gaia and Uranus |

The Greek god Oceanus is believed to be a vast freshwater river that runs its course around the ancient Greek world. The river was thought to be the fount of all water sources in the world, like rivers, wells, lakes, streams, rain clouds, and seas, and is personified as the god Oceanus.

Background of the Greek God Oceanus

Mythology has long taught us how people understood the makeup of the world and its physical and philosophical spheres. Oceanus fulfilled a cosmological role as a vast fresh-water river and the origin of all fresh-water sources on land and the moisture in clouds.

The river ran around the flat disk of the earth and served as a boundary denoting the divisions of the realm of men and gods and titans.

The river Oceanus was geographically and mythologically important and was often a place of far shores where the more mysterious islands were rumored to reside, such as that of the Gorgons, the Hesperides, and the palaces of the Sun and Moon. The Titan of the ocean himself is said to reside in a palace with his wife Tethys somewhere in his great river.

Detail of a mosaic showing Oceanus and Tethys with various water creatures (2nd-3rd Century); Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail of a mosaic showing Oceanus and Tethys with various water creatures (2nd-3rd Century); Adam Jones from Kelowna, BC, Canada, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

While his name is taken to mean “great sea or river”, the exact origin of his name ‘Ôkeanos’ and its alternative form ‘Ōgenós’ is unknown. His name ostensibly functions as the ancient Greek word for ocean. Suggestions have placed it as Pre-Greek, Semitic, or even originating from a hypothetic Proto-Indo-European word meaning “lying on” that alludes to his usual depiction in a reclining position that references his place lying around the world.

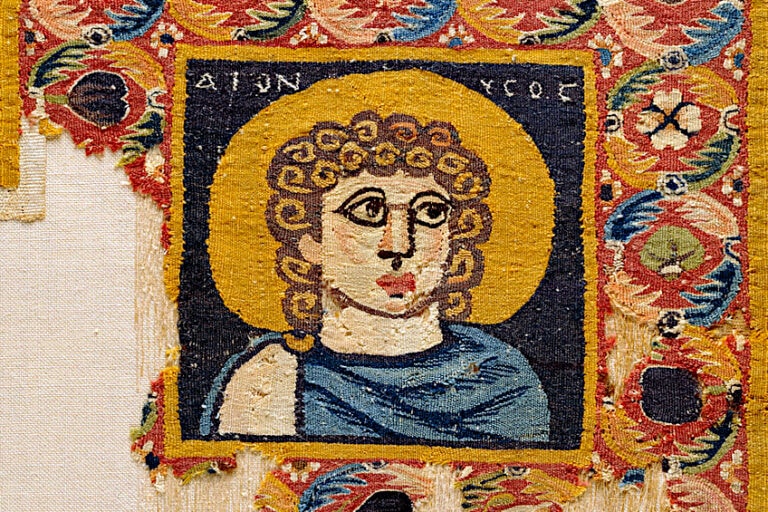

Oceanus’ Family

Oceanus is the eldest of the twelve or thirteen original titan children of the primordials Uranus, the sky, and Gaia, the earth. He is the eldest of the Titans, and his siblings according to Hesiod’s Theogony (7th century BCE) are Cronus, Hyperion, Iapetus, Theia, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, Coeus, Crius, and Tethys. Through his parents, he is also sibling to the groups of the Hecatoncheires, the Cyclopes, the Gigantes, the Erinyes, the Meliae, and half-siblings to gods such as Aphrodite, Pontus, and more.

Oceanus took his sister the Titaness Tethys as wife and with fathered the many river and water gods and goddesses, named Potamoi and Oceanids respectively.

Both groups are ostensibly numbered at 3000 each, though are considered to be innumerable, and only the more significant or eldest of them have names. Examples include the Oceanids Metis who bore Athena, Clymene the wife of Iapetus, and the sacred river Styx in the underworld. Oceanus is also father to the Nephelai, the nymph daughters of clouds who bore pitchers of water from their river siblings and nourished the earth with rain.

Oceanus’ daughters the Nephelai; artist’s impression

Oceanus’ daughters the Nephelai; artist’s impression

He was also said to have fathered the two humorous thieves known as the Cercopes by Theia the daughter of King Memnon, and a possible parent of the Eleusinian demi-god prince Triptolemus. Oceanus’ grandchildren are numerous and include gods such as Nike, Iris, Kratos, as well as groups like the Nereids, the Charites, and the Harpies, to name a few.

The Significance of the Greek Titan of the Ocean

Oceanus plays two main roles in the Greek world. The first role he plays is that of the great water source from which nourishing waters across the world flow. The second role he plays is that of a location and boundary marker in the mythic geography of ancient Greece.

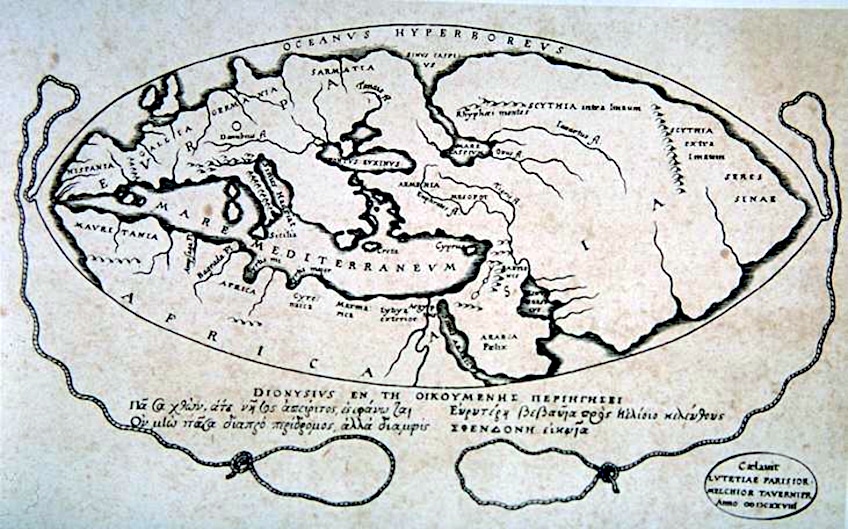

World map based on the description of Posidonius showing Oceanus (150-130 BCE); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

World map based on the description of Posidonius showing Oceanus (150-130 BCE); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Father of Water

The Greeks believed there was one source of all water in the world, who was Oceanus the great river. Every river, spring, sea, and well is said to flow from and back into the great Stream Oceanus. There is some degree of separation between Oceanus being a freshwater river and being the source of saltwater and identified with the sea.

Pontus is the personification of the sea, but the distinction between freshwater and seawater is not always made.

In Homeric poetry (8th century BCE), Oceanus has been called a “begetter of the gods” and “begetter of all things”, though these are isolated descriptors. This is supported by the notion that the earth and cosmos rose from primordial waters, and in some writings across the centuries he is referred to as either being the same generation as Uranus and Gaia or the source from which all gods and life arose. His role as “father” and his wife as “mother” of the gods may be a metaphorical title, such as due to their fostering of Hera. Generally, Oceanus’ only confirmed role as a “begetter of life” comes from his role as the source from which all the innumerable water sources flow and the life these waters bring.

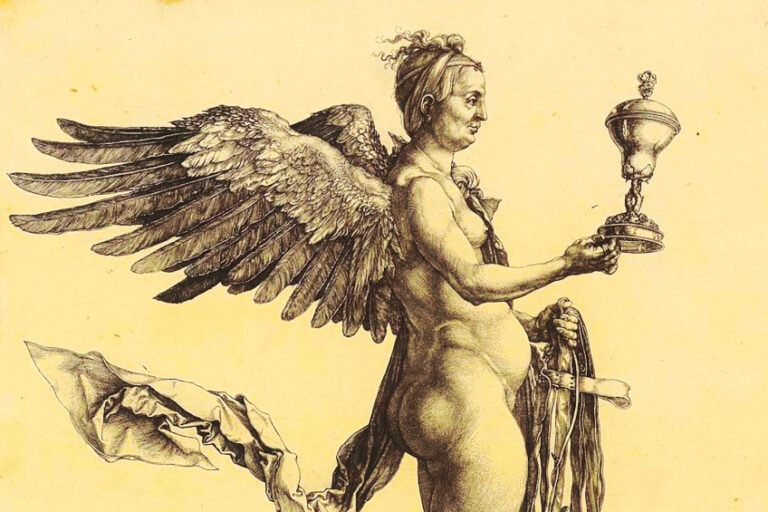

Greek God Oceanus as source of life; artist’s impression

Greek God Oceanus as source of life; artist’s impression

Through his many children, he also serves as a genealogical source of many figures of Greek myth and legend. Just as all water sources branch from him, so we can trace influential figures of myth back to him. His wife Tethys has been said to dispense her husband’s nourishing waters around the world through underground aquifers.

The Boundaries of Oceanus

Oceanus marks the ends of the earth, and in several myths is a boundary separating the realm of men from dwellings of monsters and gods. The Gorgons and Hesperides are placed in the far East beyond his waters and Hesiod and Homer place Oceanus near to Hades and Tartarus.

Fantastical races and exotic peoples were said to dwell in or beyond his domain beyond the Pillars of Hercules, though with the discovery that they were saltwater Oceanus became more closely associated with Pontus.

As geography advanced through the ages, Oceanus came to signify the farther and unfamiliar oceans, Poseidon still ruled the local Mediterranean Ocean but waters like the Atlantic were represented by Oceanus. It has been argued that Oceanus was more a primordial elemental than a god of waters, which can be used to somewhat reconcile Oceanus’ role as the source of all waters with the domains of the various sea gods.

Mosaic showing Poseidon in his chariot holding his trident with Oceanus and Tethys below (2nd-3rd Century); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mosaic showing Poseidon in his chariot holding his trident with Oceanus and Tethys below (2nd-3rd Century); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Oceanus is also a boundary between the heavens and the sea. All celestial bodies, the sun, moon, and stars, rise from and descend into Oceanus waters. After night has fallen, Helios is said to sail back along the stream so as to rise from the east again. His palace and that of his sister Selene the moon, is also said to reside in Oceanus in the East.

Only one heavenly denizen was exempt from bathing in the great stream, and that was the constellation Callisto, a former nymph barred by jealous Hera after her affair with Zeus. This explained why the constellation Ursa Major never went beyond the horizon.

The Great River’s Attributes and Attitudes

His exact personality is largely unknown due to the briefness of his interactions in myth but he remained rather popular throughout ancient Greece. His representations lend him a reputation as a kind and benevolent figure. He certainly has enough children to support his fatherly representations, helped along by his age placing him as an older generation even among the gods and his bearded imagery.

His lack of involvement in overthrowing Uranus, his indirect support of the Olympians through his daughter Styx and the goddess Hera, and his faltering before Hercules’ threats, can be interpreted as cowardice like Prometheus did in Prometheus Bound.

Even if his harboring of Hera during the Titanomachy is considered or not, Oceanus’ actions lend him a more passive air. He seems more indifferent to things happening outside his waters than other gods of myth, seemingly content to avoid conflict throughout mythology. This pacifism is mostly in stark contrast to his bellicose fellow Titans and his tempestuous sea-successor the “earth-shaker” Poseidon. While he could be destructive Oceanus is also seen generally as fatherly and a source of life, possibly through his many children being water sources across the land.

Statue of a reclining Oceanus (2nd Century CE); Eric Gaba, Wikimedia Commons user Sting, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of a reclining Oceanus (2nd Century CE); Eric Gaba, Wikimedia Commons user Sting, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Depictions and Symbols Associated With Oceanus

Oceanus is primarily a part of Greek cosmogony in the form of a vast river and is described as such by Homer and Hesiod, however, he is also represented as a personification in art and later myths. As a river, Oceanus is described as “the perfect river” by Hesiod. Other descriptions by the writer include “deep-swirling” while Homer calls him “deep-flowing” and that he “bounds the earth”.

Both these Archaic period poets refer to Oceanus as “backflowing” into itself, and the great stream encircling the earth is represented on several shields of heroes by encircling their rims.

Oceanus as a personification has been depicted with many attributes over the centuries. In artwork depicting Peleus and Thetis’ wedding, he is envisioned as having bull horns and his lower half being that of a fish. What little remains of another depiction of the same event shows him with a bull’s head. Mosaics often depicted him as having the upper half of a well-built man and the lower half of a serpent. His horns may count one or two, often his horns are the claws of crabs and he sports a full beard.

Athenian black-figure dinos with a depiction of Oceanus at the wedding of Thetis and Peleus by Sophilos (c. 590 BCE); © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Athenian black-figure dinos with a depiction of Oceanus at the wedding of Thetis and Peleus by Sophilos (c. 590 BCE); © Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Oceanus’ main symbols include that of a serpent and fish, which is often depicted as holding in his hands. In his more humanoid presentations, his lower half is also often presented as a serpentine fish. As a god of water, he is naturally associated with marine creatures and fish.

Serpents in Greek mythology usually have chthonic and primordial connotations, as well as associations with life and death, and often serve as symbols of wisdom and divine messages.

The Legacy and Influence of Oceanus

Oceanus remained relatively popular compared to other Titans but not as popular as the Olympians and not so popular as to be worshiped in any large capacity. Titans and primordials serving mythology as concepts and locations in the natural world are commonplace, and often have little to no focus in cults or everyday life.

Oceanus was fundamentally an explanation of what the ancient Greeks thought about water sources and how the world they lived in came to be.

It is within the realm of possibility that he may have had some localized worship or place of honor in mystery cults due to his role with water sources or his chthonic and primordial ties. Ultimately, he had little cult presence outside of one notable instance, where Alexander the Great worshiped him during his campaign to conquer the world. Oceanus has been featured in numerous European artworks, such as mosaics and statues. One of his most famous depictions is his iconic statue in the late baroque masterpiece known as the Trevi Fountain in Rome. Legend has it that those who throw coins into the fountain will return to Rome, similar to how all waters flow back to Oceanus.

The Trevi Fountain by Nicola Salvi and Giuseppe Pannini (1732-1762); gnuckx, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Trevi Fountain by Nicola Salvi and Giuseppe Pannini (1732-1762); gnuckx, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Oceanus’ Appearance in Myth

As one of the original twelve Titans, Oceanus was beseeched by Gaia to overthrow her husband and their father Uranus after he imprisoned their children beneath the earth. According to Hesiod only Kronos, the youngest, rose to the challenge and defeated his father. Other tellings have all the Titans, aside from Oceanus, agreeing and eventually succeeding in surprising and castrating Uranus before installing Kronos as king.

A poem by Plato, Timaeus, contains some lines describing Oceanus angrily fretting, considering whether he should join the attack on Uranus but ultimately does not.

His role in the Titanomachy is uncertain but he is confirmed to have been on the sidelines of the conflict. His house is said to have sheltered the Titanides, as well as Hera and other goddesses, though he is also said to have advised his daughter Styx to join Zeus’ side in the conflict alongside her children Nike, Zelus, Bia, and Kratos. Whether he fought at all is unknown, however, he is not named as being imprisoned and seems to have continued as normal after. If his claim over waters counted the seas, then Poseidon did claim part of his domain; however, Oceanus is generally considered overall as unaffected by the cosmic regime shuffle.

Detail from the frieze on the Great Altar of Pergamon showing Nereus, Doris, a fallen Giant, and Oceanus (2nd Century BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from the frieze on the Great Altar of Pergamon showing Nereus, Doris, a fallen Giant, and Oceanus (2nd Century BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In Prometheus Bound, Oceanus visits Prometheus in his punishment and advises his nephew to humble himself before Zeus but receives only Prometheus’ mockery. Another myth Oceanus appears in is as an obstacle to the hero Heracles as he was fetching the cattle of Geryon. The god sends waves to rock Helios’ cup that Hercules was riding, however after Heracles threatens to shoot him the god is sufficiently intimidated and backs off.

Oceanus has also been identified in the Altar of Pergamon frieze depicting Gigantomachy, he fights on the side of the Olympians and a figure behind him has been suggested as his wife Tethys.

Oceanus’ character may have several connections to figures of Orphic Theogonies, such as the primordial water god Hydros, the king of the Titans Ophion and his wife Eurynome the daughter of Oceanus, and Khronos and Ananke, whose serpentine coils were said to encircle the cosmos.

What You Can Learn from Oceanus?

Oceanus’s main appearances in mythology are in places of change and transition, whether it be in primordial myth or godly wars. An odd point of stability in all the upheaval, he is largely a bystander, displaying a passivity usually unseen amongst Titans. Whether by contentment or cowardice, he is largely uninvolved in, but not resistant to, change. Of all the gods it is Oceanus that goes largely unaffected by the conflicts and is seemingly most content to ignore all that goes on outside his watery domain in the river.

Oceanus encircling the world; artist’s impression

Oceanus encircling the world; artist’s impression

Oceanus is the backflowing river from where all water springs and all water returns, and has been through numerous changes to reflect progressing theories of geography, and yet he somehow remains much the same. Oceanus shows us that some things only persist by changing, and that constancy and change are not mutually exclusive but interlinked. We exist because we are reacting and making choices but we are also conserving ourselves.

Change is inevitable but going with the flow does not have to mean terrifying transitions and high stakes, but rather adapting to your new context.

Staying true to yourself and doing what is best for you may seem like cowardice to others, but ultimately it is your choice how you navigate choppy waters and keep yourself afloat. Oceanus may not have been held in high esteem after the succession wars of Greek mythology, but he neither did he lose anything like others. Oceanus flows as constant, and subtly vital, as ever in the world, showing us that consistency and careful consideration can be just as rewarding as relentlessness and daring.

The Greek god Oceanus is a figure that teaches us how the ancient Greeks understood their world. As the origin of all water sources and a boundary between the mundane and fantastic, he represented a consistency in the cosmos and brought life throughout the natural and mythological world. While not a well-worshiped figure, the claw-horned and fish-tailed Titan has always occupied an intriguing place in mankind’s wonderings and wanderings about the world, and we hope we have sparked your own interest through this article.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Does Oceanus Look Like?

Oceanus has two main forms in myth, owing to him being the god and personification of the Great River Oceanus. As the river Oceanus, he is the deep, swirling, and gigantic world-encircling fresh water. As a humanoid, he is usually depicted as an older man with the lower hair of a fish or serpent, and the upper hair of a muscular man. He is also usually bearded and horned, sometimes having a bull’s head. He is often depicted lying down or riding some form of sea creature.

Who Was Oceanus in Greek Mythology?

Oceanus was the great freshwater river believed to surround the world, and his very name functions as the ancient Greek word for ocean. It served as a boundary between the world of the Greeks and their more mythical and exotic geography, such as islands of monsters, palaces of the celestial gods, or the Underworld itself. Oceanus was the father of rivers, lakes, wells, and clouds, as well as the origin from which all water flowed.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.