Greek God Adonis – Epitome of the Beauty of Mortality

Adonis is the consort of the great Greek goddess Aphrodite. He not only features in her mythology, but also enjoyed an ancient cult associated with her. According to Adonis’ mythology, he was Aphrodite’s mortal lover, and while he is now associated with desire and beauty, in the ancient world he was primarily an agricultural fertility god. The origins of the Greek cult of Adonis most likely lie in Cyprus, and has been traced further back to the Phoenician gods Adon and the Babylonian Dumuzi/Tammuz. Let’s find out more about Adonis’ mythology by answering questions such as “how did Adonis die?”, and “what is the symbol of Adonis?”.

Contents

Exploring the Greek God Adonis’ Mythology

| Name | Adonis |

| Gender | Male |

| Personality | Serious and obedient |

| God of | Desire, beauty, mortality, seasonal rebirth |

| Symbols | Anemone, fennel, and lettuce |

| Consorts | Aphrodite and Persephone |

| Children | Beroe and Golgos |

| Parents | Theias and Myrrha |

In ancient mythology, the Greek god Adonis was a beautiful young man who was the goddess Aphrodite’s all to mortal lover.

The cult practices associated with Adonis suggested that he was an agricultural fertility deity associated with the life-cycle of crops.

He came to be regarded as the archetypal dying-and-resurrected deity in early 20th-century religious research. In the present day, the name Adonis is used as a noun to describe any young man who epitomizes male physical beauty.

Adonis by Sophie Fremiet (19th Century); Sophie Fremiet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Adonis by Sophie Fremiet (19th Century); Sophie Fremiet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Background and Family

Adonis’ mythology was well-known in ancient Greek culture, and it inspired a number of hymns, poems, and artworks. His appeal and awful fate rendered him a symbol of fleeting beauty, mortality, and the universality of loss and grief. Let us start by taking a look at Adonis’ parents.

Adonis’ Parents and Children

Theias (or Cinyras in some accounts) is believed to be Adonis’ father. He is normally portrayed as the mortal ruler of Phoenicia or Assyria.

Adonis’ mother, Myrrha, was also a mortal, and she was also Theias’ own daughter.

This made Adonis’s birth the consequence of incest, but we will see later, that relationship was forced upon the king and his daughter by the gods as punishment.

Myrrha and Cinyras (Theias) by Antonio Zanchi (mid to late 17th or early 18th Century); Antonio Zanchi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Myrrha and Cinyras (Theias) by Antonio Zanchi (mid to late 17th or early 18th Century); Antonio Zanchi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As for Adonis’ children, Beroe and Golgos, they too do not seem to have left any significant stories in Greek mythology besides being referred to as the offspring of Adonis.

Role in Mythology

If he came from such a relatively insignificant background, why was he so adored by Aphrodite and why was this mortal revered as the Greek god Adonis? Perhaps we can find out the answer by exploring Adonis’ mythology regarding his birth, life, and death. Let’s start with his birth.

The Birth of Adonis

According to the Roman poet Ovid’s rendition of the story, Adonis was the child of Myrrha. Myrrha’s mother had boasted that her daughter was even more beautiful than Aphrodite. The enraged goddess instilled an insatiable passion in the young girl for her father King Theias. Myrrha confessed her terrible desire for her father to her nurse. Later, during the feast of Demeter, the nurse discovered the King drunk, with Myrrha’s mother nowhere to be found.

The nurse told the king about a girl who wanted to sleep with him, providing a false name and only identifying her as being Myrrha’s age.

The King consented, and the nurse immediately brought Myrrha to him. Myrrha was pregnant when she left her father’s chamber. After many of these encounters, the King eventually discovered the true identity of his young lover and pulled his sword to kill her. She fled, seeking sanctuary with the gods. They turned her into a myrrh tree, and Adonis was born from this tree.

The Birth of Adonis and the transformation of Myrrha by Luizi Garzi (c. mid-to late 17th or early 18th Century); After Garzi, Luigi (Italian painter, 1638-1721) Previously attributed to Fetti, Domenico (Italian draftsman and painter, ca. 1589 -1623) Previously attributed to Italian (Bolognese) School, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Birth of Adonis and the transformation of Myrrha by Luizi Garzi (c. mid-to late 17th or early 18th Century); After Garzi, Luigi (Italian painter, 1638-1721) Previously attributed to Fetti, Domenico (Italian draftsman and painter, ca. 1589 -1623) Previously attributed to Italian (Bolognese) School, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The resin of the Myrrh tree was widely used in the ancient Mediterranean as a perfume, insence used in religious rites, and for medicinal purposes. The Egyptians also used it in the embalming of bodies, which may help to explain why Adonis was believed to have been born from this tree.

Aphrodite and Persephone

In some versions of his myth, Adonis was the illegitimate result of a short-lived fling between two unnamed humans. When his parents abandoned him at birth, Aphrodite, who had infused his parents with their adulterous desire in the first place, felt either pity or guilt and saved the infant from certain death.

However, for some inexplicable reason, Aphrodite decided to ask the queen of the dead to raise him in the underworld.

Persephone had no children and gladly took Adonis in. When Aphrodite returned a few year later she was captivated by the grown Adonis’ exceptional beauty. Persephone loved Adonis and desired to keep him in the underworld, so Zeus settled the argument by declaring that the young man would spend 1/3rd of the year with Persephone, 1/3rd with Aphrodite, and the last 1/3rd with whoever he wanted.

Adonis, Aphrodite, and Persephone by Johannes Schöpf (1771); HaSt, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Adonis, Aphrodite, and Persephone by Johannes Schöpf (1771); HaSt, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Adonis picked Aphrodite, and they were always together after that. According to another story, the Muse Calliope suggested that both deities have possession of him for half a year each. Adonis’ life was therefore split between spending time with Persephone and Aphrodite, one goddess loving him from the world beneath and another from the world above.

The Death of Adonis

Adonis later died in Aphrodite’s arms after being injured by a wild boar while out hunting one day. According to various versions of the tale, the boar had either been sent by the Greek god Apollo to get back at Aphrodite for blinding Erymanthus (Apollo’s son), or by Artemis to exact revenge on Aphrodite for killing her dedicated supporter Hippolytus, or even perhaps by her lover, the jealous war-god Ares, to exact revenge upon Aphrodite for spending all of her time with the attractive youth.

Adonis by Antonio Corradini (c. 1723-25); Antonio Corradini, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Adonis by Antonio Corradini (c. 1723-25); Antonio Corradini, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The tale also explains the origin of Aphrodite’s connections to particular flowers. According to legend, when she grieved for Adonis’s passing, she caused anemones to sprout wherever his blood spilled and announced a celebration for the day after his passing.

In a subsequent version of the story, his blood was said to have changed into roses. According to one version, Aphrodite was hurt by a thorn from a rose, and her blood turned the formerly white rose to a red color. In another version, a red rose grew wherever Aphrodite’s tears dropped.

According to a significantly different account from the traditional one that was preserved in the writings of Servius in the 5th century CE and may have come from the island of Cyprus, Aphrodite herself forced Adonis to fall in love with a mortal girl called Erinoma at Hera’s request. In this version, Adonis sneaked into Erinoma’s bedroom and sexually assaulted her after she turned down his approaches. Erinoma was a virgin who was valued by Athena and Artemis. Zeus, who also adored Erinoma and would undoubtedly get revenge for the brutality committed against her, pursued Adonis as he escaped and into a cave. But Hermes tricked him, and Ares diguised as a wild boar gored Adonis in the groin. Aphrodite eventually pleaded to Zeus for his life, and Adonis was eventually brought back to life.

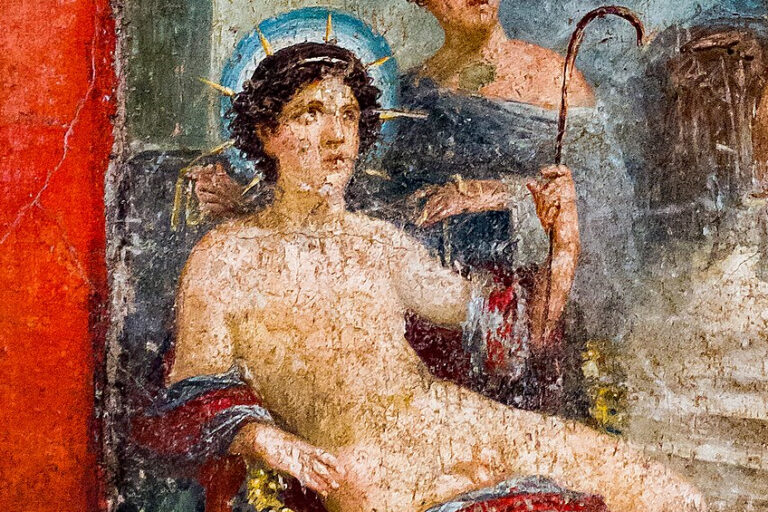

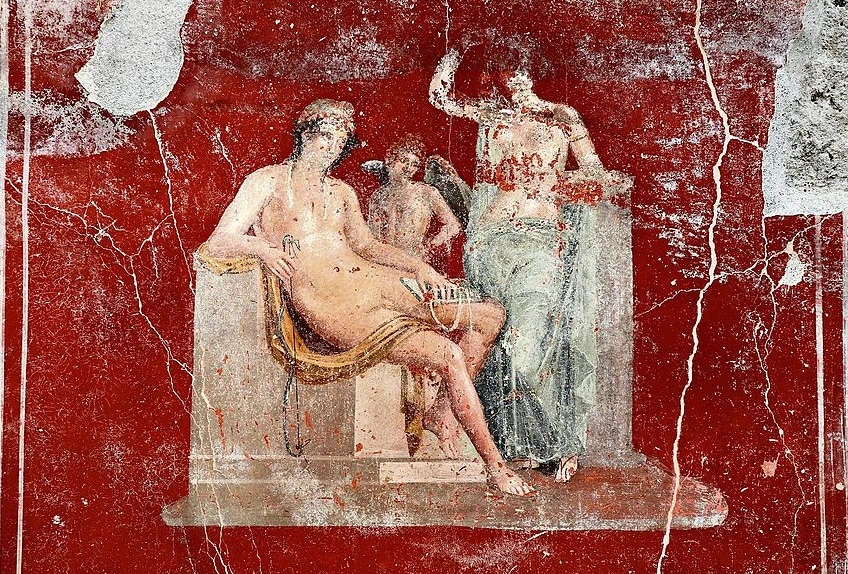

Fresco from Pompeii depicting Adonis with Cupid and Aphrodite (1st Century BCE to 1st Century CE); English: Prairie SmokeРусский: Дым Прерий, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco from Pompeii depicting Adonis with Cupid and Aphrodite (1st Century BCE to 1st Century CE); English: Prairie SmokeРусский: Дым Прерий, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Role as a Dying and Risen God

Sir James George Frazer, a Scottish anthropologist from the late 1800s, wrote extensively on the Greek god Adonis. Frazer stated that Adonis was simply a single instance of the “dying-and-rising deity” theme common in all civilizations.

Some academics started criticizing the term in the mid-20th century, contending that gods like Adonis would be better termed “disappearing gods,” claiming that deities who “died” didn’t come back, and those who came back never actually died.

Eager to differentiate the death and resurrection of Christ from those of pre-Christian gods, Biblical scholars Boyd and Eddy applied similar logic to Adonis, arguing that his time with Persephone in the underworld of Greek mythology was not a death and rebirth, but rather an instance of an actual human being in the Underworld.

Venus (Aphrodite) Mourning the Death of Adonis by Frans Floris the Elder (16th Century); Frans Floris I, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Venus (Aphrodite) Mourning the Death of Adonis by Frans Floris the Elder (16th Century); Frans Floris I, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite these scholars’ assertion that Adonis is not expressly referred to as returning from the dead in any existing Classical Greek works, writers in Late Antiquity had observed the existence of such a belief.

Origen, for instance wrote of the cult of Adonis that “for a long time specific ceremonies of initiation have been carried out: first, that they mourn for him since he died; second, that they celebrate him, as he had risen from the dead.”

The difference between Christian and Ancient Greek notions of death and rebirth is that in Christian mythology, Christ was part of a godhead made human, who died once, and then returned to his divine state after death. Adonis by contrast, dies and returns to life on a cyclical basis. He represents mortality as a necessary part of all forms of life.

The Worship of Adonis

Adonis and Aphrodite’s worship is most likely a Greek offshoot of the ancient Sumerian adoration of Dumuzid and Inanna. During King Manasseh’s reign, the cults of Dumuzid and Inanna might have been brought to the Kingdom of Judah. Ezekiel 8:14 identifies Adonis by Tammuz, his older East Semitic name, and recounts a group of women sitting by the north entrance of the Temple in Jerusalem grieving Tammuz’s death.

The first known Greek allusion to Adonis is found in a small portion of a poem by Sappho of Lesbos, wherein a group of young girls asks Aphrodite what they might do to grieve Adonis’ passing.

Aphrodite responds by telling them to pound their breasts and shred their tunics. The worship of Adonis has also been compared to the cult of Baal, the Phoenician deity. “They sat at the gate mourning for Tammuz, or they plant pleasant plants or burn incense on roof-tops to Baal”, Walter Burkert stated. He continued, “These are the same characteristics of the Adonis myth: Adonis gardens, which are honored on flat roof-tops with sherds sowed with rapidly growing green vegetation.

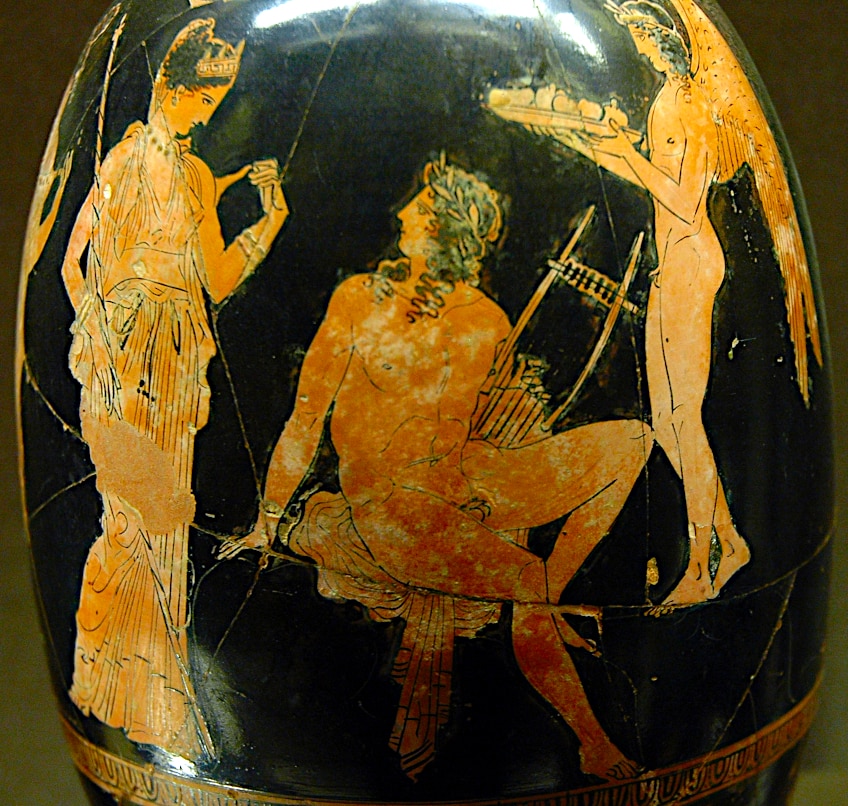

Attic red-figure hydria with a depiction of hetairai and female slaves celebrating the festival of Adonis (c. 360-350 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure hydria with a depiction of hetairai and female slaves celebrating the festival of Adonis (c. 360-350 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The end result is a powerful lament for the deceased deity”. The precise period when Adonis’s worship was incorporated into Greek society is still debated. Burkert doubts that Adonis did not come to Greece with Aphrodite right from the very start. In Greece, the special role of the Adonis mythology is as a vehicle for the unbridled display of passion in the tightly confined lives of women, as opposed to the strict order of the household.

The considerable effect on early Greek religion by Near Eastern culture in general, and on the development of the cult of Aphrodite on the island of Cyprus particularly, is now largely acknowledged to have occurred during a period of orientalisation in the 8th century BCE, when ancient Greece was on the outskirts of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

The Festival of Adonia

Adonis worship is related to the Adonia festival, which had been observed by Greek women annually in July. The celebration, which was certainly held on Lesbos by Sappho’s era during the 7th century BCE, appears to have gained popularity in Athens in the mid-5th century BCE. At the outset of the celebration, the women would start a “garden of Adonis”, a tiny garden planted within a shallow fragment of broken pottery holding a variety of fast-growing plants like fennel and lettuce, as well as grains like barley and wheat.

These women would then ascend ladders to their dwellings’ rooftops, where they would proceed to arrange their little gardens in the summer sun. In the daylight, vegetation would emerge, but in the heat, it would wither.

They would offer incense to the Greek god Adonis while they awaited for the plants to grow and eventually die. Once the greenery had withered away, the worshipers would publicly weep and mourn the passing of Adonis, ripping their clothing and pounding their breasts. A figurine of Adonis would be spread out on a bier, and women would proceed to carry it to the sea in a funeral procession with all the dead plants. The ceremony culminated with the worshipers casting Adonis’ effigy and the wilted vegetation into the waters below.

Scene from a modern celebration of the Adonia where ancient rituals are re-enacted; Αρχαία Ελληνική Θρησκεία, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Scene from a modern celebration of the Adonia where ancient rituals are re-enacted; Αρχαία Ελληνική Θρησκεία, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Adonis in Literature

Over the years, the tale of Adonis and Aphrodite has been recreated and reinterpreted in art, literature, and popular culture in many different kinds of ways. Various versions emphasize various aspects of the narrative, allowing for a variety of individual and cultural interpretations. In his contributions to the Roman de la Rose, published around 1275, Jean de Meun, the medieval poet from France, recounts the tale of Adonis.

De Muen moralizes the incident, stating that men ought to pay attention to the cautionary words of the women they adore. Venus regrets that he did not hear her warning in Pierre de Ronsard’s verse “Adonis” (1563), but eventually blames herself for his passing, claiming, “when in need my advice failed you”.

Yet, in the same verse, Venus immediately looks for another shepherd to be her lover, illustrating the popular medieval notion of women’s fickleness. During the Elizabethan period, the tale of Adonis and Venus from Metamorphoses by Ovid had a huge influence. Tapestries representing Adonis’ mythology adorn the walls of Castle Joyous in The Faerie Queene (1590) by Edmund Spencer. Later in the piece, Venus brings Amoretta to the “Garden of Adonis” to nurture her. Ovid’s depiction of Venus’s frantic love for Adonis inspired many literary depictions of courting in Elizabethan literature.

The Garden of Adonis – Amoretta and Time by John Dickson Batten (1887); John Dickson Batten, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Garden of Adonis – Amoretta and Time by John Dickson Batten (1887); John Dickson Batten, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

William Shakespeare’s recounting of Aphrodite and Adonis’ romance from Metamorphoses was among the most successful of all his works released during his lifetime. Six versions were released before Shakespeare’s passing, and it was especially popular among younger adults. Richard Barnfield commended it in 1605, asserting that it had helped establish Shakespeare’s name. Despite this, contemporary reviewers have had varied reactions to the poem. Samuel Butler claimed that the story bored him, and C. S. Lewis regarded it as “suffocating” to read. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, however, defended the work.

The Adonis mythology inspired Giambattista Marino, the Italian poet, to compose his mythical epic L’Adone (1623), which sold more copies than Shakespeare’s First Folio. Marino’s poem focused on the joys of love, which are explicitly described. It depicts the Greek god Adonis shooting the wild boar with one of Cupid’s arrows and announcing that the tusk that smashes his hip is a “loving” one.

The French playwright and novelist Rachilde was inspired by Shakespeare’s homoerotic characterizations of Adonis’s attractiveness and Venus’ aggressive quest for him when she wrote her romantic novel Monsieur Vénus (1884), which centers on an aristocratic lady named Raoule de Vénérande who is pursuing an attractive man called Jacques who is employed in a flower shop. In the end, Jacques is shot and dies in a duel, emulating Adonis’ own tragic demise.

Adonis in Art

Throughout history, Adonis has been a popular topic in art, and his depiction has evolved across many creative styles and times. Adonis often appeared as a young and beautiful young man in ancient Greco-Roman art. He was often depicted as having an idealistic, athletic physique and perfect facial features. He was represented as the pinnacle of male beauty in works of art such as ancient sculptures and vase paintings.

Attic red-figure lekythos with a depiction of Aphrodite and Adonis (c. 410 BCE); Aison, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure lekythos with a depiction of Aphrodite and Adonis (c. 410 BCE); Aison, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Artists drew influence from Greek mythology and recreated the image of Adonis during both the Baroque and Renaissance eras. Peter Paul Rubens and Titian, among others, depicted Adonis as a naked or semi-naked figure, accentuating his physical attractiveness and sensuality. These artworks often depict Adonis with Aphrodite, portraying their intense romance.

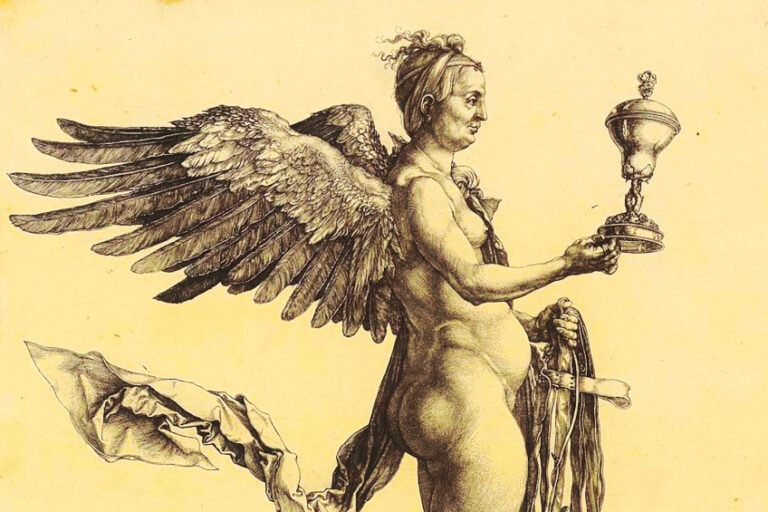

Venus (Aphrodite) and Adonis by Hendrik Goltzius (1614); Hendrik Goltzius, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Venus (Aphrodite) and Adonis by Hendrik Goltzius (1614); Hendrik Goltzius, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The myth of Adonis gained appeal in the 19th century among Romantic and symbolist painters who aspired to delve into themes of love and death. Adonis was portrayed as a figure stuck between life and death by artists like as Frederic Leighton and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, focusing on the transitory aspect of beauty.

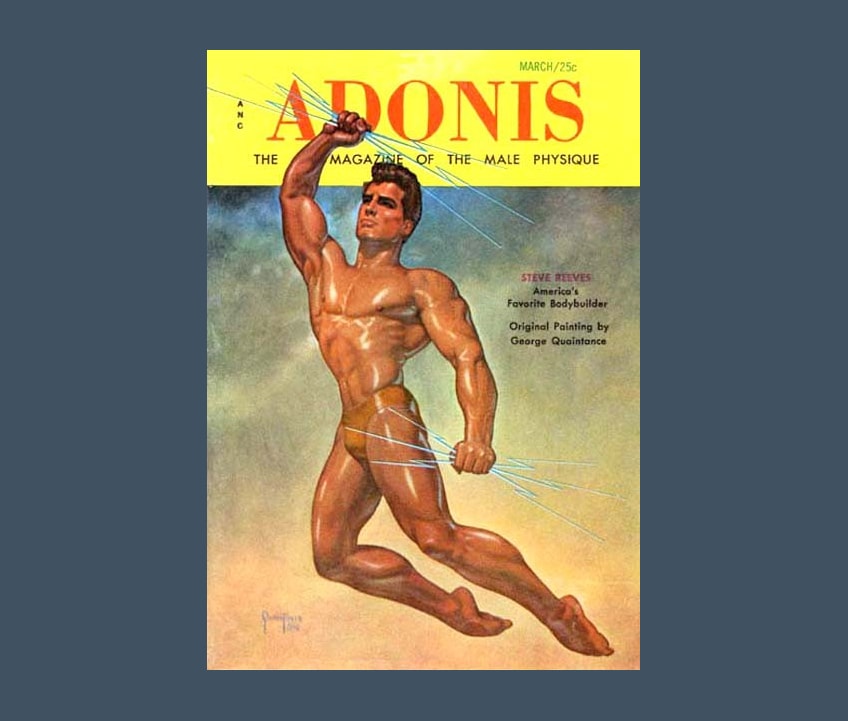

Artists keep reinventing the image of Adonis in recent years, making him more applicable to current concerns and issues.

Some artists use Adonis as a representation of both gender and sexual identity, questioning stereotypes of masculinity. Others use pop culture elements or employ Adonis as a symbol for societal standards of beauty.

Cover of the March 1957 issue of Adonis magazine by George Quaintance; George Quaintance, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Cover of the March 1957 issue of Adonis magazine by George Quaintance; George Quaintance, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Significance and Meaning of the Adonis Mythology

The mythology of Adonis and Aphrodite was important in Greek and Roman culture, as well as in literature and art in later centuries. It conveyed a wide range of issues and concepts that were relevant to the people of that time. The story first and foremost emphasized the strength of love and desire. The goddess of love, Aphrodite fell deeply in love with Adonis because of his incredible beauty. Their powerful bond represented the irresistible attraction of desire and passion and the intense nature of romantic relationships.

The sudden and tragic demise of Adonis acted as a reminder of the transient nature of life. The story illustrated the life-death cycle, with Adonis’ death signifying the wilting vegetation in winter and his subsequent rebirth representing the restoration of life in spring.

This aspect of the tale illustrated the fleetingness of human existence and the inevitability of death and transformation. Aphrodite’s intense sadness and grieving over the death of Adonis represented the human emotions associated with loss and grief. It represented the depths of emotional agony that may be felt when a loved one has passed away, emphasizing the emotional capacity of both gods and man.

The Death of Adonis by Auguste Rodin (after 1888); Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Death of Adonis by Auguste Rodin (after 1888); Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Adonis mythology came to be associated with the seasonal cycle, notably the shift from winter to spring. His mythology was often linked to natural and agricultural cycles, depicting nature’s rebirth and the reawakening of life after a dormant period. In terms of modern interpretation and moral precepts, Adonis’ mythology continues to invoke themes of desire, love, and death. The tale emphasizes the need for enjoying the beauty in our lives while it is still there. It also acts as a warning, implying that unbridled desire or jealousy might have disastrous effects.

So, is Adonis a Greek god or not? Some consider him a mere mortal, whereas others see him as the Greek god representing mortality itself. One thing that is for sure, though, is that his appearance was definitely divine! Well, at least divine enough to capture the attention and desire of the goddess of love herself, Aphrodite (or Venus in Rome). God or not, Adonis’ mythology has been significant enough to result in his worship, with various festivals and celebrations occurring to commemorate his death in winter and symbolic rebirth every spring. It is for this reason that vegetation is a symbol of Adonis, particularly vegetation that is short-lived and wilts with the onset of winter.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Adonis Die?

Even though Adonis may have socialized with the gods (and even made a few of them fall in love with him), he was actually just a mortal boy who happened to be particularly good-looking. It was during a hunting expedition one day, that Adonis was maimed and killed by a wild boar. The details of the circumstances leading up to the encounter differ from one version of the story to another, but the common thread through all of them is that he died from a fatal wound incurred by a boar.

What Is the Symbol of Adonis?

The symbol of Adonis is said to be the anemone. When he died, anemones grew from his spilt blood (in some versions, roses). He is also associated with lettuce and fennel, and any other seasonal plant that wilts when winter arrives.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.