Greek God Helios – The All-Seeing Eye of the World

What is Helios the god of, and what are Helios’ symbols? The Greek god Helios in ancient mythology is the god of the sun, and he is often portrayed steering a horse-drawn cart across the skies, wearing a radiant crown. He is also regarded as the god of sight, as well as the guardian of oaths. Join us in our discovery of the Greek god Helios, as we find out about the myths associated with this god, as well as interesting facts, such as Helios’ Roman name.

The Mythology of the Greek God Helios

| God Name | Helios |

| Gender | Male |

| Symbols | Aureole, rooster, heliotrope, and white horse |

| Personality | Powerful, tireless, and bright |

| Domain | Oceanus |

Though the Greek god Helios was regarded as a minor deity in Classical Greece, his worship became increasingly popular in late antiquity due to his association with numerous significant Roman sun divinities, including Helios’ Roman name, Sol, and Apollo.

In the 4th century CE, Julian the Roman Emperor proclaimed Helios the central god during the brief revival period of old Roman religious traditions. The God of the sun, Helios, appears regularly in Greek mythology, literature, and poetry.

Red-figured calyx-krater depicting Helios in his chariot (c. 430 BCE); British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Red-figured calyx-krater depicting Helios in his chariot (c. 430 BCE); British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Background and Family of Helios

Helios was a significant divinity whose abilities were not always acknowledged. From his position in the sky, he witnessed numerous significant events in the daily lives of the other divinities. Nonetheless, Helios, as the god of the sun, was often portrayed as remaining in the background, watching everything that happened both on Earth and in the skies while going about his daily activities.

Helios depicted on a Roman sarcophagus (early 3rd Century CE); Baths of Diocletian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Helios depicted on a Roman sarcophagus (early 3rd Century CE); Baths of Diocletian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Helios’ Family

The Titans Hyperion and Theia, were Helios’ parents, and Eos and Selene were his sisters. The ancient Greeks were controlled by these preceding pantheons of deities before the Olympians took over. This occurred after Cronus, the Mad Titan, severed Uranus’ manhood and tossed it into the sea. Hyperion served as one of the four Titans that assisted Cronus in his quest to dethrone Uranus. He and his Titan brethren were given the most heavenly of powers to wield on the mortals below: they became the pillars between heaven and Earth.

In Greek mythology, Helios’ lovers include the Oceanid water nymph, Perse, (who is regarded as his wife in some versions of his mythology), and Clymene, Rhodes, and Crete. Together with Perse, he had two daughters, Circe and Pasiphae. He also had two sons with Perse, King Perses and King Aietes.

Clymene Urging Phaeton to Find Helios by Hendrik Goltzius (1889); Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Clymene Urging Phaeton to Find Helios by Hendrik Goltzius (1889); Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

King Aietes and King Perses were his two sons by Perse. He fathered another three daughters with Clymene, who are collectively referred to as the Heliades, and was the father of Phaethon, whom Helios also had with Clymene. Along with seven sons, the sun god and Rhode had a daughter by the name of Electryone. These seven sons were claimed to be stronger and more intelligent than any of the mortal men and subsequently became Rhodes’ rulers. Three of its principal cities, Cameiros, Ialysos, and Lindos, were named after three of the sons. Phaethusa and Lampetia, a couple of Helios’ nymph daughters, oversaw his livestock on Thrinacia.

Helios’ Role in Mythology

Instead of being regarded as one of the more prominent deities, he is considered to be a background member of the Olympians. While being a relatively marginal deity, he was also one of the oldest and not one that the other gods would think of meddling with. While the ancient Greeks are rather vague on the matter, he is typically regarded as a second-generation Titan due to his lineage.

In literature from the ancient Greek period, the epithet “Hyperion’s bright son” was used when they referred to the Sun.

Helios is associated with order and harmony, both in the literal sense regarding celestial movements and in a figurative sense in terms of society. The ancient people envisioned him as a deity steering a chariot pulled by four white horses across the sky each day from east to west. Latin author Hyginus states that the chariot had been built by the Greek god Helios himself, and not Hephaestus like so many had said before.

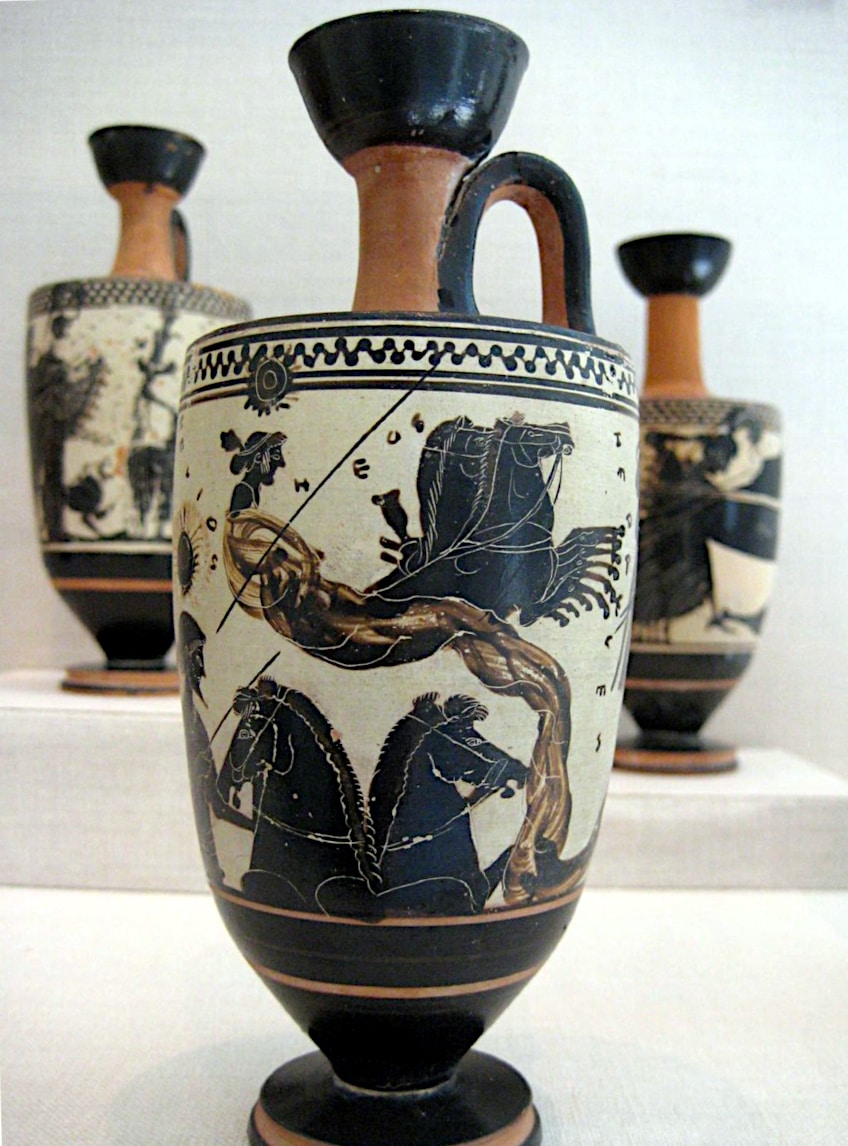

Attic black-figure lekythos featuring Helios, Nyx, Eos, and Herakles attributed to the Sappho painter (c. 500 BCE); Claire H., CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic black-figure lekythos featuring Helios, Nyx, Eos, and Herakles attributed to the Sappho painter (c. 500 BCE); Claire H., CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Helios’ sister Eos is considered to be the embodiment of dawn who was tasked with opening the gates for him every day and sometimes joined him on his journey across the sky. While it is not stated whether he went to the deep abyss known as Tartarus, it is believed that he went under the earth at sunset every night.

The Personality and Attributes of Helios

Helios was often portrayed as arrogant and proud, as befitting a potent god in command of one of nature’s most powerful forces. He was also conceited, as he was said to spend a lot of time gazing at his own reflection on the water’s surface. However, Helios was also regarded as a fair and just god, as he was believed to look over the world and make sure all was in balance.

As the “Eye of the World” Helios was called upon to testify to oaths and commitments, and he was regarded as a dependable and trustworthy source of wisdom and insight.

Fresco depicting Helios, Dionysus, and Aphrodite from Pompeii (c. 60-79 CE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco depicting Helios, Dionysus, and Aphrodite from Pompeii (c. 60-79 CE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Physical Appearance

It would be unjust to clothe the Greek sun deity in common mortal fabrics. Helios, though, has been the biggest casualty of the Greeks’ eternal propensity to make the gods’ attire look so humble. He does, though, have a plethora of symbols and props that identify his personality. In most depictions, he is a young man dressed in a gleaming aureole, and his fire-spun clothing shines as he rides his four-winged steeds through the sky every day. Helios is lauded in Hymn to the Sun as the “lord of light”.

According to the hymn, Helios has a “luminous and brilliant countenance” that brightens the globe and provides joy to everyone who sees it. The poem also implies that Helios’ heavenly radiance is so powerful that it can reach the darkest corners of the underworld.

Helios by Johannes Benk (1889); © Hubertl / Wikimedia Commons

Helios by Johannes Benk (1889); © Hubertl / Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, Helios is depicted in Metamorphoses as a magnificent and powerful deity who leads the sun’s chariot. Helios is described as “clothed in flames” in the poem, implying that his appearance is both awe-inspiring and threatening. Ovid further mentions that Helios’ daily trip across the sky is escorted by a multitude of winged horses and nymphs, illustrating his celestial magnificence even more.

Helios’ Symbols

Helios was connected with a number of symbols that signified his strength and control over nature. Helios’ most visible sign is the sun, which he was said to be guiding across the sky in his chariot every day. Helios is often seen traveling in a chariot drawn by four horses representing the four seasons. This chariot represented his mastery over the sun’s passage and the shifting of the seasons.

Helios was sometimes represented with a gleaming halo, symbolizing his position as a heavenly figure linked with the sun. Some representations of Helios include a rooster, who is said to signal the rising of the sun every morning.

Silver coin from Rhodes showing Helios and a rose (205-190 BCE); Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Silver coin from Rhodes showing Helios and a rose (205-190 BCE); Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In addition to being connected to music, Helios often appeared playing the lyre. Pythagoras described the movement of the sun, moon , and stars as “the music of the spheres” in reference to the seemingly choreographed “dance” performed over the months, years, and centuries by the heavenly bodies. Helios’ face became associated with Alexander the Great after he conquered half of the world. The name Alexander-Helios was well-known and associated with power and forgiveness.

Household Roman lararium figurine in the form of Alexander-Helios (1st Century CE); Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Household Roman lararium figurine in the form of Alexander-Helios (1st Century CE); Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Myths Associated With Helios

In antiquity, myths were used to explaining occurrences like shorter nights or longer days. Since the gods were synonymous with every aspect of the world at large, natural phenomena were ascribed to the activities of the gods. Helios was no exception.

Cyclical changes, spikes in heat, and every little dip in the sunshine was explained as the result of Helios responding to events both human and divine.

Helios, Aphrodite, and Ares

Aphrodite was married to Hephaestus, and any romance that occurred outside of their marriage would be regarded as infidelity. Hephaestus, on the other hand, was known as the ugliest God in the Greek pantheon, which infuriated Aphrodite. She sought various forms of pleasure before settling on Ares. Helios became enraged when he learned of this and vowed to inform Hephaestus. Hephaestus then constructed a thin net and intended to entrap his adulterous wife and Ares if they tried to come closer again.

When the moment arrived, Ares recruited a warrior called Alectryon to stand watch at the door. Then, he made love to Aphrodite. However, this inept young man ended up falling asleep, and Helios crept in to capture them red-handed.

The Entrapment of Mars and Venus from the studio of Hendrick Goltzius (c. 1590 and/or 1615 and/or 1728); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Entrapment of Mars and Venus from the studio of Hendrick Goltzius (c. 1590 and/or 1615 and/or 1728); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Helios promptly informed Hephaestus, and he later captured them in the net, exposing them to ridicule by the other gods. This incident, however, drove Aphrodite to have revenge against Helios and his whole race. Ares was enraged because Alectryon had failed to protect the entryway, allowing Helios to enter. So he transformed him into a rooster, and this is why the rooster crows every morning as the sun prepares to rise.

Helios and Boreas

Helios and Boreas were arguing about who was more powerful than the other on one lovely day. Instead of fighting to the death, the two gods resolved to settle the dispute with all the maturity they could manage. They decided to conduct a test on a human being.

The challenge was to see who could force the human to remove his cloak, and whoever did would win and take the position of the mightier one.

As a man passed in his boat, Boreas decided that he would try first. He used all of his power to compel the north wind to move the traveler’s cloak. Rather than being blown away, the poor man gripped the cloak even tighter, sheltering him from the torrents of cold wind piercing his face. Boreas admitted defeat and allowed Helios to try to work his magic.

The Sun and the Wind by Wenceslas Hollar (17th Century); Wenceslaus Hollar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Sun and the Wind by Wenceslas Hollar (17th Century); Wenceslaus Hollar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Helios gleamed brightly as he approached the cloaked man in his golden-yoked chariot. This caused the man to sweat so much that he decided to remove his cloak to cool down.

Helios and Clytie

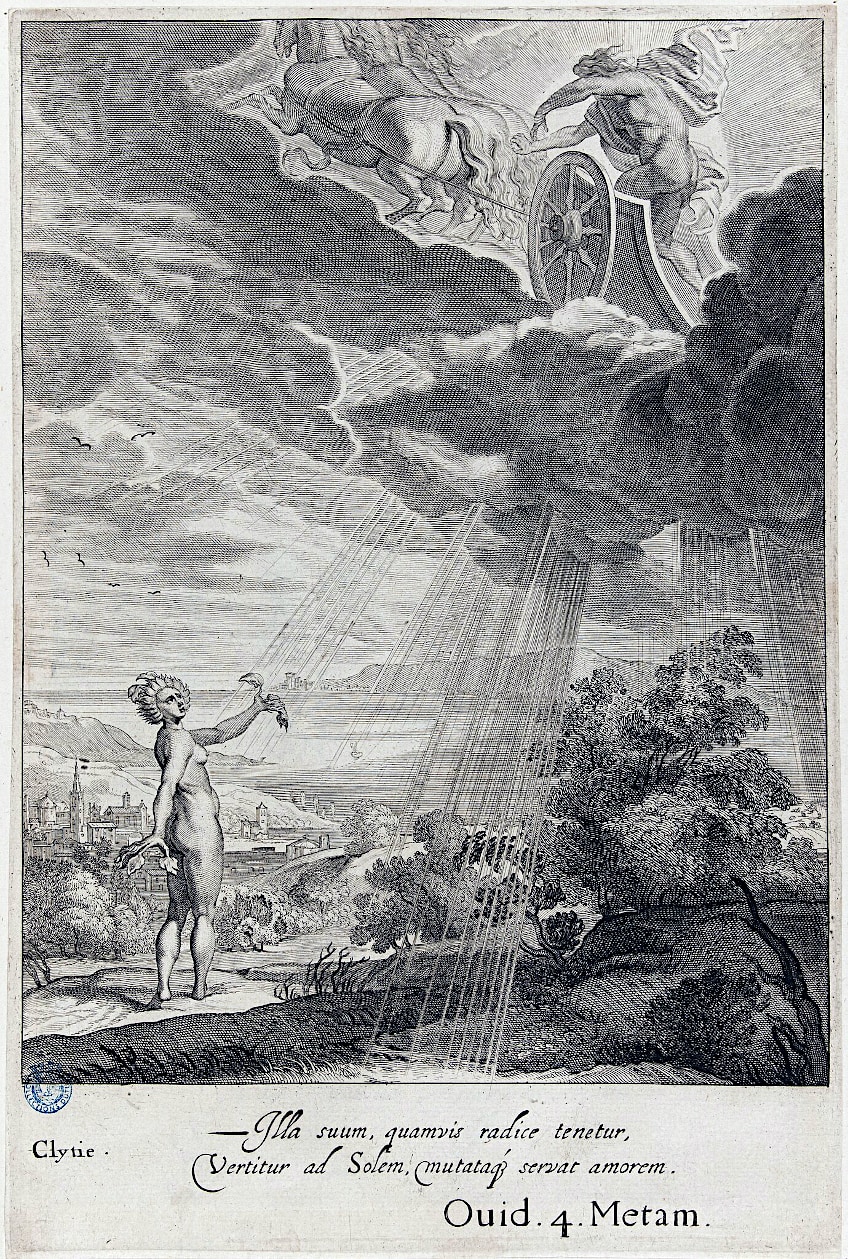

Clytie was Helios’ lover until the goddess Aphrodite made him fall in love with Leucothoe, a Persian princess, so that he could exact revenge on him for informing her husband Hephaestus of her relationship with Ares, after which he lost interest in her and all the other deities he had previously loved, such as Rhodos, Perse, and Clymene. Helios, who had once adored her, deserted her for Leucothoe. Enraged by how he treated her, she told King Orchamus, Leucothoe’s father, about the affair. Because Helios had violated Leucothoe, Orchamus had her buried alive in the sand. Helios appeared too late to rescue her, but he did ensure that she became a frankincense tree by sprinkling honey over her dead corpse, allowing her to breathe air.

Helios, according to Ovid, bears partial blame for Clytie’s intense jealousy since his adoration was never “moderate” while he loved her. Clytie planned to win Helios back by stealing his new love, but her deeds simply hardened his heart against her, and he avoided her entirely, never returning to her.

In sorrow, she stripped nude and stood on the rocks for nine days, consuming no nourishment or drinking anything, looking at the sun, Helios, and lamenting about his departure, but he never glanced back at her. Clytie eventually transformed into a purple flower, the heliotrope, which perpetually turns its head and gazes achingly at Helios as he traverses the sky in his chariot, despite the fact that he no longer thinks about her, her appearance much changed, her affection for him unchanged.

Helios and Clytie by Cornelis Bloemaert the Younger (1655); Bloemaert, Cornelis II (the Younger) (Utrecht, c. 1603 – Rome, c. 28–09–1692), engraver, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Helios and Clytie by Cornelis Bloemaert the Younger (1655); Bloemaert, Cornelis II (the Younger) (Utrecht, c. 1603 – Rome, c. 28–09–1692), engraver, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Sacred Livestock of Helios

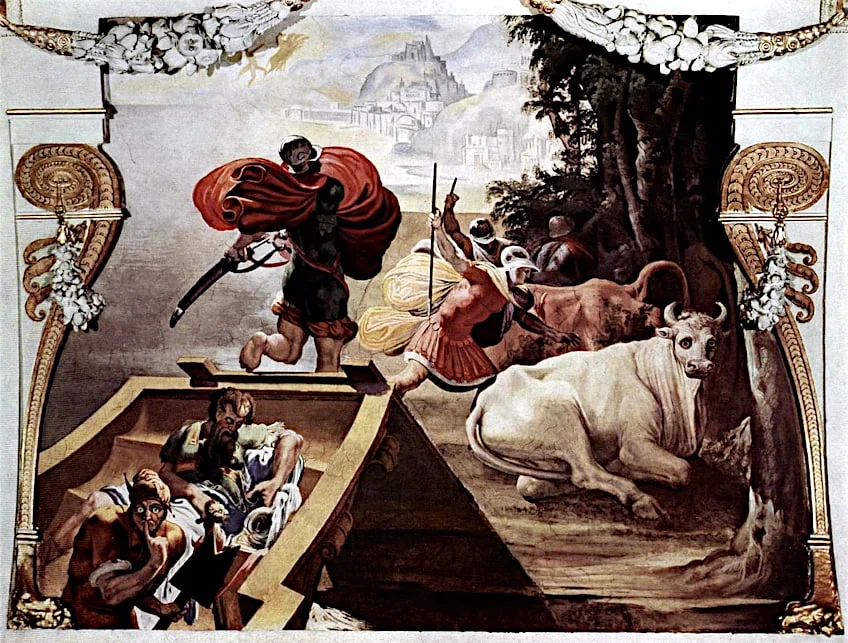

In the ancient world, owning cattle was a mark of wealth and status. Helios kept his cattle on the island of Thrinacia. The Sun’s herd of immortal cattle numbered 350, indicating the entire number of days in a year according to the ancient Greek calendar. These animals were separated into seven herds, one for each day of the week.

The most famous story relating to the sacred cattle of Helios occurs in the Odyssey. Odysseus had been warned by the goddess Circe to steer clear of Helios’ sacred cattle while passing by Thrinacia. When Odysseus and his crew arrived at the island, they had provisions, but no meat. Odysseus told his men of Circe’s warning to leave the sun god’s cattle alone. However, once he fell asleep, his men hunted down and slaughtered the sun’s cattle in the hopes of devouring them.

Helios saw what happened and appealed to Zeus to avenge this outrage or he would deprive the entire world of light. Every single member of Odysseus’ crew would die before he finally reached his home alone a decade after departing from Troy.

The Companions of Odysseus Stealing the cattle of Helios by Pellegrino Tibaldi (15554-1556); Pellegrino Tibaldi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Companions of Odysseus Stealing the cattle of Helios by Pellegrino Tibaldi (15554-1556); Pellegrino Tibaldi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In another tale, the sun god kept a flock of sheep in a safe sanctuary in Apollonia. A man named Peithenius, or Euenius in other versions of the myth, was tasked with guarding them when wolves devoured them. The people of Apollonia banded together against Peithenius who was accused of falling asleep on the job. They punished him by ripping his eyes out.

This infuriated Helios, and as a response, he dried up the grounds of Apollonia, preventing its residents from reaping any harvests. Fortunately, they made amends by gifting Peithenius a new home, thereby appeasing the sun god.

Helios and the Titanomachy

The Titanomachy was a bloody conflict between the generation of gods known as the Titans and the new gods called the Olympians after Zues’ stronghold of Mount Olympus. This war established the Olympian gods as the rulers of the universe. The Titans did not hold back as Cronus and Zeus clashed. Wanting their fair share of glory, the Olympians and Titans engaged in a 10-year battle.

Helios refrained from fighting against the Olympians and also took their side in the battle against the giants.

Helios attacking the Giants accompanied by Thetys, Oceanos and Eos (2nd Century CE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Helios attacking the Giants accompanied by Thetys, Oceanos and Eos (2nd Century CE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Worship of Helios

Helios was a major deity in ancient Greece, and he was revered in various parts of the country. Helios worship was especially popular on the Greek island of Rhodes, where the gigantic Colossus of Rhodes, was a statue of the sun god. Helios worship was often paired with festivals and celebrations In Athens, for instance, the Lenaia festival was held in January in honor of Helios and Dionysus, and the Heliaia festival was held in the summer in honor of Helios. He was also honored with countless temples and shrines across ancient Greece. The most renowned of them was the Helios Sanctuary at Rhodes.

Helios temples could also have been found in Corinth, Athens, Delphi, and many more places. Helios’ worshippers would frequently make animal sacrifices or various other offerings at his sanctuaries and temples.

Architrave with sculpted metope showing sun god Helios in a quadriga from the temple of Athena (c. 300-280 BCE); Neoclassicism Enthusiast, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Architrave with sculpted metope showing sun god Helios in a quadriga from the temple of Athena (c. 300-280 BCE); Neoclassicism Enthusiast, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

These sacrifices were thought to be a manner of expressing respect and thanks to the god. Helios’ worship was frequently coupled with sun worship, as he was thought to be the personification of the sun. This resulted in some blending of Helios with other sun gods, including the Egyptian god Ra. Helios was affiliated with astrology in addition to his status as a sun god. He was seen as a strong and important celestial force and was sometimes connected with other celestial bodies, such as the planet Mars.

Fragment of a Roman copy of a 5th Century BCE statue of Helios featuring a sash decorated with Zodiac symbols (1st Century CE); Vatican Museums, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fragment of a Roman copy of a 5th Century BCE statue of Helios featuring a sash decorated with Zodiac symbols (1st Century CE); Vatican Museums, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Although the deity was not widely worshiped, Plato tells us in his writings that many individuals, including Socrates, would welcome the Sun and give prayers every day. More direct and formal Sun worship was seen by the Greeks as a point of separation between people of other races and themselves; they did not practice it, but ‘barbarians’ did. Although one of the lesser gods, the 5th-century BCE philosopher Anaxagoras of Clazomenae caused controversy when he claimed that the Sun was not a deity but a massive blazing rock based on his calculations.

From the 5th century BCE, the god Apollo was associated with the Sun, and that connection grew stronger throughout the Hellenistic period, owing partly to the impact of Greek philosophers who started putting greater emphasis on celestial bodies.

Helios and Apollo became nearly synonymous at that point, much as Helios and Hyperion had in the Archaic era. The Romans took it a step further and declared Helios, also known as Sol, a cult deity. From the third century BCE, the Circus Maximus in Rome housed a temple devoted to Sol and the Moon. The worship of Sol became more popular throughout the imperial period, particularly during the reigns of emperors Elagabalus and Aurelian in the 3rd century CE. The latter was also the son of a Sun priestess.

A devoted priesthood known as the pontifices Solis oversaw what had become the most significant imperial religion, a position it would occupy until Christianity took over.

Magic sphere with a depiction of Helios and various magical symbols, possibly used for rituals aimed at ensuring victory (2nd or 3rd Century CE); Deiadameian, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Magic sphere with a depiction of Helios and various magical symbols, possibly used for rituals aimed at ensuring victory (2nd or 3rd Century CE); Deiadameian, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Legacy and Influence of Helios

Helios’ legacy can be seen in many areas of life, such as science, mythology, and philosophy. Helios also appeared frequently in Greek art as well as on coinage and other objects.

One of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Colossus of Rhodes, was a massive statue of Helios which greeted ships as they entered the harbor. Created from bronze plates with iron reinforcement, it was a feat of art, engineering, and marketing all in one. The Statue of Liberty can be considered a modern version of it.

Colossal statue of Helios possibly in the tradition of the Rhodes Colossus from the sanctuary of Serapis in Egypt (138-161 CE); Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Colossal statue of Helios possibly in the tradition of the Rhodes Colossus from the sanctuary of Serapis in Egypt (138-161 CE); Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The term “heliocentrism” in astronomy refers to the belief that the sun is the central point of the solar system, and it is named after Helios. In ancient Greek philosophy, the sun was seen as a source of light and wisdom. Plato, for instance, used the sun as an analogy to define the nature of knowledge and the truth.

Helios’ influence can be found in a variety of cultural and intellectual realms, ranging from science and philosophy to art and language. His importance and popularity in ancient Greek culture is still felt today. As the God of the Sun, he rises every morning and begins his journey across the sky in his magnificent chariot. From his lofty position, he is able to witness all the activities of the other deities. As the embodiment of the sun, he has appeared in many other times and cultures, such as in Rome, when he was known as Sol, which is Helios’ Roman name.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Helios the God of in Greek Mythology?

Helios was largely regarded as the sun god in Greek mythology. As the sun’s personification, he was thought to be in charge of driving the sun’s chariot across the sky every day. Along with his role serving as the sun god, Helios also had a number of prominent offspring and successors in Greek mythology, such as Phaethon, who failed in his attempts to steer his father’s chariot, and Circe, the enchantress widely recognized for her participation in Odysseus’ adventures in Homer’s Odyssey.

What Roles Did Helios Play?

Helios was sometimes linked with various parts of the natural world in addition to his status as a sun god. For instance, he was sometimes shown with wings, signifying his capacity to fly over the sky like a bird. He was also linked to horses, which were said to pull his chariot over the sky. His chariot was believed to be built of gold, with horses pulling it called Aeos, Aethon, Aethon, and Phlegon. In some myths, he is also associated with truth and justice, as he was able to get a good view of events from his position in the sky.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.