Greek Goddess Hecate – The Ancient Queen of Witches

What is Hecate the goddess of, and how does Hecate appear to others? The Greek goddess Hecate is considered to be the goddess of witchcraft. The Greek goddess of magic, Hecate, is also considered to be the goddess of crossroads, ghosts, the phases of the moon, and poisonous plants. In earlier art, she appeared in singular form, but later she acquired triple-bodied and triple-headed forms. Below, we will find out more about this important goddess of Greek mythology.

Contents

- 1 Understanding the Role of the Greek Goddess Hecate

- 2 Background and Family

- 3 The Greek Goddess of Magic’s Attributes

- 4 The Domains of the Goddess of Witchcraft

- 5 Hecate’s Mythology

- 6 The Worship of Hecate

- 7 The Greek Goddess Hecate in the Roman Era

- 8 The Lessons of the Greek Goddess of Magic

- 9 Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding the Role of the Greek Goddess Hecate

| Name | Hecate |

| Gender | Female |

| Symbols | Paired torches, serpents, dogs, daggers, keys, and Hecate’s wheel |

| Personality | Loyal and compassionate |

| Domains | Sky, Earth, and the sea |

| Parents | Perses and Asteria |

| Spouse | None |

| Children | Aegialeus, Circe, Empusa, Medea, and Scylla |

Along with Hestia, Zeus, Apollo, and Hermes, Hecate was one of the numerous divinities worshiped in ancient Athens as a guardian of the household. It has been said of Hecate’s cult that she is more inclined to exist on the edges than in the heart of Greek polytheism. She transcends traditional boundaries and eludes description because she is intrinsically ambiguous and polymorphous.

Statue of a triple-headed Hecate (3rd Century CE); Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of a triple-headed Hecate (3rd Century CE); Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Background and Family

Whether Hecate’s worship began in Greece or not, some academics believe the name is derived from a Greek root, and numerous possible source words have been found. For instance, ἑκώv (willing) is associated with the name Hecate.

Another Greek term proposed as the source of the name Hecate is, an ancient epithet of Apollo that means “the far-reaching one.”

This has been proposed in relation to the traits of the goddess Artemis, who was strongly linked with Apollo and was often associated with the Greek goddess Hecate in the ancient world.

Statue depicting the syncretic goddess Artemis-Hecate (3rd century BCE); Fanny Schertzer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue depicting the syncretic goddess Artemis-Hecate (3rd century BCE); Fanny Schertzer, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to supporters of this theory, Hecate was formerly regarded as an aspect of Artemis before the latter was accepted into the Olympian pantheon. There is certainly evidence of a cult of a syncretic goddess called Artemis-Hecate. It is plausible that over time, Artemis could have become increasingly linked to maidenhood and the idea of purity, while her darker traits, such as her relationship with magic, the spirits of the night, and death became more closely associated with Hecate.

Family

She was typically referred to as the offspring of the Titans Perses and Asteria, although there were many different stories of her origins, including those that said she was Zeus’ daughter. Perses is a mysterious person in Greek mythology; his significance appears to have been restricted to his genealogical duty as Asteria’s spouse and Hecate’s father.

The ancients didn’t have much to say about Perses or his characteristics. Hesiod, the poet, did, however, praise him as “eminent among all men regarding wisdom”.

Role

Hecate, the great goddess, presided over several territories. By the 5th century BCE, she was primarily associated with ghosts, the Underworld, the moon, various animals (particularly creatures of the night and dogs), female initiation (including childbirth and marriage), agricultural activities, and entrances to both private and public areas (such as doorways, crossroads, and fortifications). Thus, Hecate’s role included almost all facets of human existence, including death. Hecate’s role evolved significantly throughout time.

Though she is not mentioned in Homer, she appears in Hesiod’s Theogony, where she was substantially different from the later Hecate as goddess of magic with a role in the underworld.

Hesiod extols Hecate as a goddess whom the son of Cronus, Zeus, adored above all. Hecate, according to Hesiod, had a share of the land, sky, and sea, but not the Underworld, and she helped all mortals: soldiers, monarchs, shepherds, athletes, mothers, fishermen, children, and so on. In light of later developments, Hesiod’s Hecate is nearly unrecognizable. She had evolved into a considerably darker, more terrifying image by the 5th century BCE.

Hecate as a predominantly chthonic figure; artist’s impression

Hecate as a predominantly chthonic figure; artist’s impression

Though she was still sometimes considered to be friendly or helpful (the poet Pindar characterized Hecate as a kind virgin at this time), she had mostly grown to be recognized as a goddess of witchcraft, the darkness, and the Underworld. It’s unclear how or why this transition occurred.

The Greek Goddess of Magic’s Attributes

Hecate was shown in the beginning like any other deity, modestly robed and often sitting. Other depictions have her wearing a short chiton like Artemis and carrying two flaming torches. By around 430 BCE, she had developed her characteristic triple-bodied form. This iconography mirrored Hecate’s position as a goddess of the crossroads, with one body or face representing each of the crossing routes, allowing Hecate to keep an eye on all of them at the same time.

Statues of the three Hecates immediately gained popularity. These depictions, known as hecataea, were usually displayed on columns or poles near crossroads as well as in front of private dwellings.

Hecate Symbols

Aside from her triple-bodied or headed form, the Greek goddess Hecate was usually recognized due to wearing a polos, a type of cylinder crown, and torches.

Relief depicting a Triplicate of Hecate (c. 1st Century CE); Zde, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Relief depicting a Triplicate of Hecate (c. 1st Century CE); Zde, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hecate was usually accompanied by dogs. The howling of these dogs was thought to signal Hecate’s approach when she traveled at night, followed by a group comprised of the souls of the dead – particularly the souls of childless or unmarried girls. Snakes, swords, red mullets, polecats, flowers, boughs, and pomegranates were among Hecate’s other qualities and emblems.

Some accounts even depicted Hecate as the keeper of the keys to the Underworld.

Iconography

Her oldest known depiction is a tiny clay figure discovered in Athens. The text on the figure is a dedication to the Greek goddess Hecate written in 6th-century style, although it lacks any additional Hecate symbols traditionally connected with the goddess. She is posed seated on her throne, with a chaplet on her head; the rest of the depiction is quite basic.

A 6th-century ceramic piece from Boeotia portrays a goddess, possibly Hecate, in the aspect of a mother or fertility deity. She is crowned with lush branches and depicted bestowing a motherly blessing on two maidens who hug her.

An animal often connected to Hecate and seen on coinage and reliefs from Asia Minor are lions, which flank the image. In ancient Greek artwork, Hecate is often depicted as three sculptures standing back to back, each with its own unique set of characteristics.

Statuette of triple-bodied Hecate encircled by three dancing Graces (1st-2nd Century CE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Statuette of triple-bodied Hecate encircled by three dancing Graces (1st-2nd Century CE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to the writer from the 2nd century, Pausanias, the Greek goddess Hecate was first represented in triple form by Alcamenes the sculptor in the late 5th century BCE Greek Classical era, whose statue was erected before the temple of the Wingless Nike in Athens. Whereas Greek anthropomorphic painting traditionally depicted Hecate’s form as three distinct bodies, Hecate’s iconography gradually developed into images of the goddess of witchcraft with a singular body with three faces. In Egyptian-inspired esoteric texts from Greece associated with Hermes Trismegistus, Hecate is depicted as having three heads: one snake, one dog, and one horse. Her animal heads in other portrayals include that of a cow and a pig.

Detail showing Hecate with animal heads from The Greek Gods. Diana by Wenceslas Holler (17th Century); Wenceslaus Hollar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail showing Hecate with animal heads from The Greek Gods. Diana by Wenceslas Holler (17th Century); Wenceslaus Hollar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The eastern frieze of Hecate’s Hellenistic temple at Lagina depicts her assisting in the protection of the king of the gods, Zeus, from his father Cronus; this frieze is the only proof of Hecate’s role in the tale of his birth.

Hecate’s Sacred Animals

As we mentioned earlier, in the Classical era, dogs were often identified with Hecate. Hecate can often be seen portrayed as dog-shaped or alongside a dog in art and literature. Hecate’s customary sacrificial animal was the dog, which was frequently eaten in solemn ceremonies. Dogs were sacrificed to Hecate at Samothrace, Thrace, Athens, and Colophon. A racehorse owner dedicated a marble relief from the 4th century in Crannon in Thessaly. It depicts Hecate, accompanied by a dog, laying a garland on a mare’s head.

Roman statuette of triple-headed Hecate astride a horse; Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman statuette of triple-headed Hecate astride a horse; Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Her affiliation with dogs is said to be suggestive of her association with birth, as dogs were sacred to Eileithyia, Genetyllis, as well as other birth goddesses.

Images of her being accompanied by a dog may also be seen when she appears in reliefs alongside the goddess Cybele and the deity Hermes in her function as mother goddess with child.

Although the Greek goddess Hecate’s dogs were subsequently believed to be an embodiment of restless souls who accompanied her, its subservient appearance and connection with the Greek goddess of magic suggests that its original meaning was positive and thus more likely to have developed from the dog’s relationship to birth than its associations with the underworld.

Hecate’s Sacred Plants

Hecate was linked to plant lore and the creation of poisons and medicines. She was said to teach these closely linked arts in particular. In sections of Sophocles’ lost play, the goddess is portrayed as wearing oak, and an old text portrays her as having a head encircled by snakes tangled through oak branches. The yew was considered holy to Hecate by the Greeks. Her attendants wrapped yew wreaths over the necks of black bulls killed in her name, and yew branches were ignited on funeral pyres. Hecate was reported to prefer garlic offerings, which were strongly associated with her worship.

Hecate is also sometimes connected with cypress, a tree associated with dying and the underworld and so devoted to many Chthonic deities.

Hecate is connected with a variety of different therapeutic and dangerous plants. Aconite, dittany, belladonna, and mandrake are among them. It has been claimed that employing dogs to dig up the mandrake root is further confirmation of the plant’s association with Hecate; in fact, there is an abundance of evidence of the seemingly prevalent custom of using dogs to look for plants associated with magic dating back to at least the 1st century CE.

Anthropomorphic mandrake root (between 1501 and 1700); See page for author, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Anthropomorphic mandrake root (between 1501 and 1700); See page for author, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Domains of the Goddess of Witchcraft

The Greek goddess Hecate is not only the goddess of magic in ancient Greek mythology. She also serves as the goddess of boundaries, the moon, and the underworld. In the following chapter, we shall find out more about her role in these various domains.

The Greek Goddess of Boundaries

Hecate was connected with borders, gateways, city walls, crossroads, and, by extension, the living world. Hecate appears to have been especially linked with being “between places”, and is hence usually referred to as a “liminal” deity. Hecate served as a bridge between the Titan and Olympian regimes, as well as the celestial and mortal realms.

Apulian red-figure hydria with a depiction of Hecate and a dog guiding Nike’s chariot by the Baltimore painter (c. 320-310 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Apulian red-figure hydria with a depiction of Hecate and a dog guiding Nike’s chariot by the Baltimore painter (c. 320-310 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hecate would gain a reputation as a deity who might choose to avert the demons, or even motivate them to work against unlucky individuals.

Hecate’s connection with Enodia, a Thessalian goddess, by the mid-fifth century was most likely due to her duty as protector of entrances.

This role appears to be related to Hecate’s iconographic link with keys, as well as her presence with two torches, which when placed on either side of a door or gate lit the nearby area and allowed guests to be identified.

Goddess of the Underworld

The Greek goddess Hecate was also seen as a Chthonic goddess because of her involvement with borders and boundaries, in addition to the liminal areas between realms. She could open the gates of death as the possessor of the keys that open the gateways between the various realms. The Greek goddess Hecate, like Hermes, takes on the function of protector on all voyages, including the one to the underworld. She is depicted in myth and art as assisting Hermes in escorting the Greek goddess Persephone back from the underworld with her burning torches.

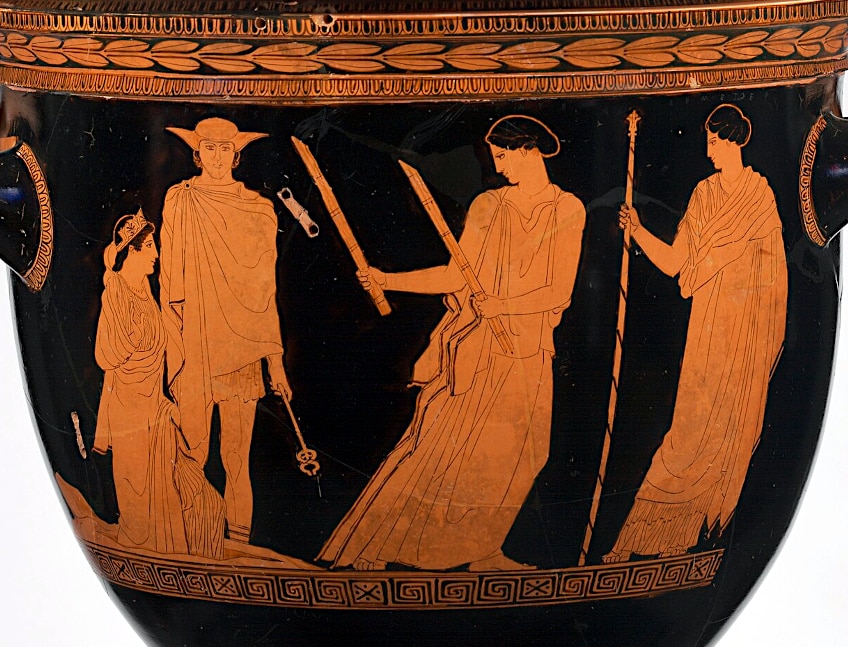

Attic red-figure bell-grater with a depiction of Hermes and Hecate guiding Persephone as she emerges from the Underworld (c. 440 BCE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure bell-grater with a depiction of Hermes and Hecate guiding Persephone as she emerges from the Underworld (c. 440 BCE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Greek goddess Hecate had become strongly associated with ghosts by the 5th century BCE, possibly as a result of confusion with Enodia, the Thessalian goddess, who traveled with an entourage of ghosts and was portrayed on coinage sporting a leafy crown along with torches, both of which have a strong connection with Hecate.

Goddess of Witchcraft

Hecate’s chthonic and nocturnal nature led to her transition into a deity primarily linked with witches, witchcraft, and sorcery by the 1st century CE. The witch Erichtho summoned Hecate in Lucan’s Pharsalia as “Persephone, the final and lowest incarnation of Hecate, the deity that we witches adore”, and portrays her as a “rotting deity” who must “put on a mask when she approaches the deities in Olympus”. Because the dog, like Hecate, is an animal of the threshold, the keeper of portals, it is suitably connected with the border between life and its demise, as well as demons and spirits that wander through it.

Cerberus, the monster watchdog, defended the gaping gates of Hades, whose purpose was to keep those who were alive from entering and those who died from leaving.

Goddess of the Moon

Hecate was regarded as a triple divinity, associated with Diana (hunting) on Earth and the deity Luna (Moon) in the sky, while she represented the Underworld. Hecate’s link with Helios in literary sources, particularly in cursing magic, has been offered as proof for her lunar origin, albeit this evidence is somewhat late; no artwork tying Hecate to the Moon appears until the time of the Romans.

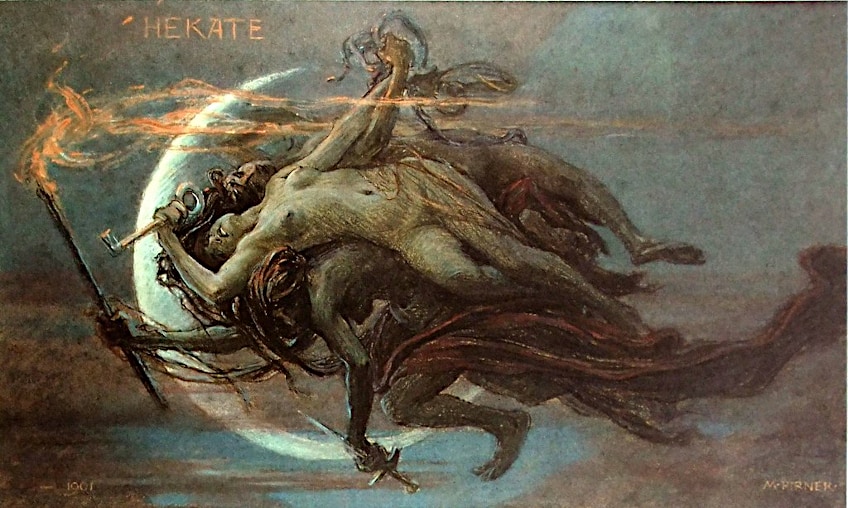

Hekate by Maximilian Pirner (1901); Maximilian Pirner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hekate by Maximilian Pirner (1901); Maximilian Pirner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nonetheless, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter depicts Hecate and Helios letting Demeter know about Persephone’s abduction, a prevalent topic found in several regions of the world in which the Moon and Sun are questioned about events on Earth in light of the fact that they can witness everything, and the hymn suggests Hecate’s capacity as a goddess of the moon.

In Medea by Seneca, the eponymous Medea greets Hecate as the “orb of the night”. Hecate and Selene were also regularly linked with each other as well as an assortment of Greek and non-Greek gods.

Hecate’s Mythology

Hecate initially shows up in ancient literature in the Theogony by Hesiod in the 7th century BCE. Hesiod only describes her parents and her involvement in the Gigantomachy, in which she slew Clytius. Hecate is, however, not included in the Homeric epics. She does, though, appear in a few other Greek myths.

Hecate and Demeter

Hecate’s portrayal in the Hymn to Demeter by Homer is probably her most well-known portrayal in ancient Greek literature. When Hades abducted Persephone, Hecate and Helios, the sun god, heard her grieving. Hecate informed Demeter about the kidnapping and encouraged her to seek the assistance of Helios, who had watched the proceedings. Hecate then joined Demeter on Mount Olympus, where they petitioned Zeus for Persephone’s return. Hecate remained a presence in the story when Persephone was given permission to go back to the surface world for a portion of the year.

Phrygian grave marker depicting a Triple Hecate flanked by Demeter and another fertility goddess below two stars and the moon (3rd Century CE); anonymous, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Phrygian grave marker depicting a Triple Hecate flanked by Demeter and another fertility goddess below two stars and the moon (3rd Century CE); anonymous, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hecate served as Persephone’s associate, responsible for transporting her between the underworld and the world above when the seasons changed. Hecate served as an intermediary and guide between the realms of the dead and the living in Homer’s Hymn to Demeter.

The Worship of Hecate

In antiquity, Hecate was worshiped with other deities in big temples and shrines, and she played an important role as a household deity. Shrines to Hecate were usually placed at the entrances to residences, temples, and towns with the belief that they would guard against the restless souls and other ghosts.

A little Hekataion, a shrine centered around a stone or wooden carving of a triple-formed Hecate gazing in three different directions on each side of a central pillar, was a typical kind of domestic shrine.

Larger Hekataions, usually contained inside tiny walled spaces, were occasionally constructed at public crossroads near major monuments, such as the route leading to the Acropolis. Similarly, temples to Hecate were built at three-way intersections, where offerings of food were presented at the New Moon in order to safeguard anyone who did so from ghosts and other dangers.

History

Around 430 BCE, the cult of Hecate was formed in Athens. During the same period, the sculptor Alcamenes created the first documented triple-formed Hecate sculpture for her new shrine. While the original sculpture has not survived to the current day, countless subsequent reproductions do. It has been claimed that this triple image, which is generally centered on a pole or pillar, evolved from older images of the goddess, which used three masks put on wooden poles, presumably positioned at doorways.

Hecate was a popular deity, and her worship took place in many different places across Western Anatolia and Greece.

Caria was an important religious center, and her most renowned temple was in the town of Lagina. The first known concrete proof of Hecate’s religion comes from Selinunte, where she possessed a temple in the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. It is among the oldest known artifacts devoted to the worship of Hecate, dating from the 7th century BCE. Worshipers utilized a unique sort of exchange in conjunction with her worship at Miletus: they would lay stone cubes and wreaths for protection at the doorway.

Votive relief depicting the strategoi of Mesambria honoring Hecate (2nd–1st Centuries BCE); Ad Meskens, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Votive relief depicting the strategoi of Mesambria honoring Hecate (2nd–1st Centuries BCE); Ad Meskens, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Deipnon

During the Deipnon, the Athenian Greeks honored Hecate. In Greek, Deipnon refers to the evening meal, which is often the most substantial meal of the day. At its most basic, Hecate’s Deipnon is a supper presented to the Greek goddess Hecate and the wandering dead once a month during the New Moon. On the evening of the new moon, dinner would be served outside, in a little shrine to Hecate beside the front door, because the street in front of the home and the entryway form a crossroads, which was known to be a spot where Hecate lived. Cake, fish, bread, honey, and eggs are all possible food gifts.

The main objective of the Deipnon was to honor Hecate and appease the spirits who “longed for vengeance”. A secondary function was to cleanse the family and atone for any wrongdoings committed by a household member that angered Hecate, prompting her to refuse her favor to them.

The Greek Goddess Hecate in the Roman Era

Hecate was still acknowledged and worshiped throughout the Roman era, although her popularity and significance shifted in comparison to her Greek counterpart. In the time of the Romans, Hecate’s devotion and significance were partially entwined with that of Trivia, and her traits and connotations were amalgamated with the Roman goddess. The Romans compared Hecate to their own deity Trivia, who had comparable characteristics and relationships.

Silver Roman coin with a depiction of the triple cult statue of Diana Nemorensis (Diana-Hecate-Selene) with a Cyprus grove in the background (c. 43 BCE); National Museum Wales, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Silver Roman coin with a depiction of the triple cult statue of Diana Nemorensis (Diana-Hecate-Selene) with a Cyprus grove in the background (c. 43 BCE); National Museum Wales, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Trivia was likewise regarded as the goddess of magic, crossroads, and the underworld in Roman mythology. She was also linked with the moon and appeared as a triple-bodied goddess. The name “Trivia” is said to be taken from the Latin phrase “trivium”, which alludes to a location where three roads intersect, highlighting her association with crossroads. In Roman times, masters of witchcraft regularly invoked trivia. She was said to be able to bestow or withhold magical abilities, give protection, and disclose secret information. As a goddess of the moon and night, she was also regarded as a protector of spirits and the realm of the supernatural.

Hecate remained unmarried and had no constant partner as a virgin goddess, however, some myths identify her as Scylla’s mother through either Phorcys or Phorbas.

Hecate is also said to be the goddess Circe’s mother, and Medea, the sorcerer who later came to be associated with magic while originally simply being a herbalist goddess, equivalent to how Hecate’s association with the Mysteries and underworld led to her being converted into a goddess of witchcraft.

The Lessons of the Greek Goddess of Magic

The Greek goddess Hecate represents the principle of accepting complexity and understanding life’s diverse character. She represents the stages of life and the various facets of existence as a triple goddess. Her connection to the moon underlines the constant flux of life’s cycles even more. The Greek goddess Hecate advises us to embrace and negotiate the numerous stages and transitions we go through, realizing that life is not always as straightforward as we would like.

Macbeth, the Three Witches, Hecate, and the Eight Kings, in a Cave by Robert Thew after Sir Joshua Reynolds (1802); painted by the Sir Joshua Reynolds ; engraved by Robert Thew, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Macbeth, the Three Witches, Hecate, and the Eight Kings, in a Cave by Robert Thew after Sir Joshua Reynolds (1802); painted by the Sir Joshua Reynolds ; engraved by Robert Thew, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Greek goddess Hecate is also connected with the underworld, the night, and the murky worlds. She signifies our capacity to confront and accept the darkest sides of ourselves and our surroundings. Hecate advises us not to be afraid of the unfamiliar or dark corners of our own psyche, but to investigate and incorporate them into our life in order to experience personal development and transformation.

The Greek goddess Hecate is a Greek mythological goddess who can be both benevolent and dangerous. She was connected with witchcraft, the Moon, portals, and nighttime creatures like ghosts and hellhounds. In her chthonic aspect, Hecate usually wields a torch. As the goddess of borders and the protector of crossroads, she had three faces. While she was initially depicted in a singular form, she was subsequently represented with three bodies.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Does Hecate Appear to Others?

She is usually shown on Greek pottery as a youthful woman holding a key or torch, both of which remind us of her role as a night deity, a keeper of Hades’ gates, and a goddess of limits. One 5th-century BCE Attic vase portrays a woman presenting a dog and a basket of pastries to the goddess. Her most remarkable appearance in sculpture appears in Classical and Hellenistic period representations, which feature the goddess with three heads and three bodies, typically with moonbeam haloes.

What Is Hecate the Goddess Of?

In the mythology of the ancient Greeks, Hecate was mainly regarded as the goddess of witchcraft. She was additionally believed to be the Greek goddess of magic and sorcery. The Greek goddess Hecate also played a role as one of the underworld’s goddesses, in addition to being a goddess associated with the moon.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.