Roman Mosaics – The History of Roman Tesserae Art

Ancient Roman life is shown in detail in mosaics. Mosaics offer a peek into who the Romans were, what they prized, and where they walked. They depict everything from thrilling sports bouts to sensitive depictions of the local wildlife. Roman mosaic art is stunning in and of itself, but it also offers crucial documentation of ordinary objects including clothing, food, tools, weapons, plants, and animals. Roman mosaic floor artworks also provide a wealth of information about everyday Roman pursuits like gladiator fights, athletics, farming, and hunting, and on occasion, they even include vibrant and realistic portrayals of the Roman citizenry.

Roman Mosaics: What They Reveal About Ancient Art

Ancient Roman mosaics are made up of figural and geometrical images that are assembled from smaller fragments of stone and glass. Late in the 5th century BCE, the earliest types of Greco-Roman mosaics were developed in Greece. By enclosing pebbles in mortar, the Greeks improved the skill of figural mosaics. Tesserae consisting of cubes of stone, porcelain, or glass, were used by the Romans to refine this time-tested technique in order to produce intricate, vivid images.

Boxford Roman mosaic (4th century CE), West Berkshire, England; 12dstring, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Boxford Roman mosaic (4th century CE), West Berkshire, England; 12dstring, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Today, these works provide a mental image of ancient Roman life; a look into the routines of a prehistoric society that engaged in gladiator fights, athletics, and agriculture, as well as serving as a record of commonplace objects like food, clothing, tools, and weaponry. As the Roman Empire grew, these pieces of art were displayed on the walls of both private residences and public structures. Archaeologists have discovered mosaics in a variety of contemporary locations, such as France and Tunisia, which show a blend of regional customs and Roman influence.

Roman mosaics provide unique insight into the passions and daily lives of ancient civilizations through their in-depth storytelling, and more and more examples of them are being discovered in archaeological dig sites.

The Origins and Influences of Roman Mosaics

Both the Minoans and the Mycenaeans used flooring constructed of small pebbles during the Bronze Age. In the 7th century BCE, the Near East applied a similar concept, but with recurrent patterns. Examples of Greek pebble paving from the 5th century BCE can be seen at Olynthus and Corinth. They were typically two-toned, with delicate geometric patterns on basic black backdrops. People began employing color by the end of the 4th century BCE, and Pella, Macedonia, has produced a number of outstanding examples.

Example of the Greek pebble mosaic technique: Stag Hunt Mosaic from the House of the Abduction of Helen in Ancient Pella (c. 300 BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Example of the Greek pebble mosaic technique: Stag Hunt Mosaic from the House of the Abduction of Helen in Ancient Pella (c. 300 BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Pieces of clay or lead, which were regularly used to define contours, were frequently included in these mosaics to reinforce them. But mosaics did not really take off as a form of art until the Hellenistic era in the 3rd century BCE when ornate panels made of tesserae rather than pebbles were blended into patterned flooring. These mosaics frequently tried to mimic wall paintings. Finer and more precisely cut tesserae were used as mosaics developed in the 2nd century BCE, and patterns made use of a wide variety of hues with colored grouting to compliment neighboring tesserae.

Opus vermiculatum, a style of mosaic that used complex hues and shading to give the appearance of a painting, was created by Sorus of Pergamon, who is regarded as one of its greatest artists. His work, notably his mosaic of the Drinking Doves, was widely imitated for many years after its creation. Several noteworthy instances of Hellenistic opus vermiculatum have been found in Delos and Alexandria in addition to Pergamon.

Detail of a copy of The Drinking Doves Mosaic, Pompeii, Casa delle colombe a mosaico, VIII.2.34 (1st Century CE); Dave & Margie Hill / Kleerup from Centennial, CO, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail of a copy of The Drinking Doves Mosaic, Pompeii, Casa delle colombe a mosaico, VIII.2.34 (1st Century CE); Dave & Margie Hill / Kleerup from Centennial, CO, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Due to the time and effort required to create them, these pieces were set on a marble tray or a bounded tray in a skilled workshop. Since they were usually used as focal points for pavements with simpler motifs, these objects were known as emblemata. These works of art were so prized that they were regularly handed down through families’ generations and transported for usage elsewhere. Multiple emblemata may be combined to create a single mosaic, and as time went on, the emblemata changed to mimic their surroundings and became known as panels.

Design Evolution: Roman Patterns and Motifs

Since there is such much variance in artistic excellence, public desire, and regional norms when discussing a subject like mosaics, it is challenging to represent a strictly linear development of the art form. There are, however, some notable distinctions as well as geographical variations.

At first, the Romans did not budge from the Hellenistic approach to mosaics, and they were heavily influenced by the subjects of the sea and representations of Greek mythology, as well as the makers themselves, as many names on ancient Roman mosaics were Greek. This proved that Greeks oversaw mosaic design even throughout the Roman era.

Depiction of the Greek poet Homer and the Muse Calliope from the Vichten mosaic (c. 240 CE); Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Depiction of the Greek poet Homer and the Muse Calliope from the Vichten mosaic (c. 240 CE); Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

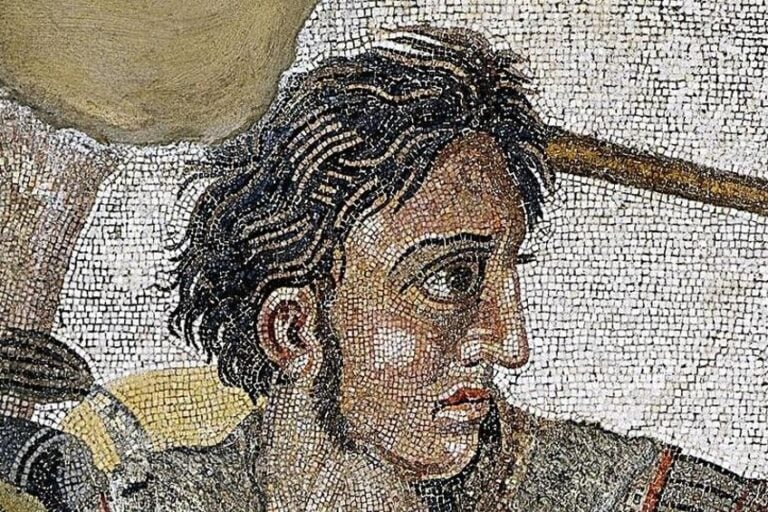

The Alexander Mosaic, one of the most iconic Roman mosaic tile mosaics, was a copy of a famous Hellenistic work by either Aristeides of Thebes or Philoxenus. It can be found at the House of the Faun and is a piece of the Pompeii mosaics.

Roman mosaics commonly imitated previous colorful ones, but gradually the Romans created their own designs, and manufacturing schools were set up all around the empire to foster their own distinct tastes. These included elaborate hunting scenes and perspective attempts in African locations, artistic greenery, and a front viewer in Antioch mosaics, or, for example, the European preference for figure panels.

The primary Roman architectural style in Italy itself was exclusively composed of white and black tesserae; this preference persisted well into the 3rd century CE and was mostly employed to depict aquatic motifs, especially when utilized for Roman baths. Two-dimensional representations with an emphasis on geometric patterns were also popular. Like the lifelike figures created at the Baths of Buticosus in Ostia around 115 CE, silhouetted figures would gain in popularity during the 2nd century CE.

Poseidon in a chariot drawn by hippocampi, surrounded with dolphins, tritons, and Nereids on sea-monsters. Room 4 of the Baths of Neptune, Ostia Antica, Latium, Italy (115 CE); Patrick Denker, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Poseidon in a chariot drawn by hippocampi, surrounded with dolphins, tritons, and Nereids on sea-monsters. Room 4 of the Baths of Neptune, Ostia Antica, Latium, Italy (115 CE); Patrick Denker, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The mosaics’ representations of people evolved over time, becoming more lifelike and accurate portraits. Meanwhile, in the 4th century CE, mosaics began to appear throughout the eastern side of the empire, particularly at Antioch. These mosaics used recurring, two-dimensional patterns to give the appearance of a “carpet.” This design would go on to have a significant impact on later Jewish synagogues and Byzantine Christian churches.

Additional Designs of Roman Mosaic Floors

Larger-scale designs can also be created by arranging floors with larger pieces. White tesserae were laid out in broad patterns or even sporadically to create the flooring for the opus signinum. The mortar aggregate used was often red. Crosses with five red tesserae and a black tessera in the middle were a popular pattern in Italy throughout the 1st century BCE and into the 1st century CE, although they were made exclusively out of black tiles.

Glass opus sectile panel possibly from the villa of Lucius Verus in Acquatraversa (2nd century CE); ); Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Glass opus sectile panel possibly from the villa of Lucius Verus in Acquatraversa (2nd century CE); ); Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Opus sectile was a type of flooring that made use of large colored stone or marble slabs that had been cut into specific shapes. Another Hellenistic technique for designing walls was opus sectile, though the Romans also employed it. It was utilized in numerous public structures, but it was not until the 4th century CE that it started to appear more frequently in private houses. Opus sectile began using transparent glass as its primary material in response to Egyptian influences.

Other Uses of Mosaics

Not only were floors covered in Roman mosaic art. Mosaics were commonly used to decorate columns, vaults, and fountains, especially in baths. The first recorded usage of pumice, marble, and shell shards was at the nymphaeum of the Villa of Cicero in Formiae in the midst of the 1st century BCE. To give the appearance of a natural grotto, marble and glass fragments were scattered in various locations.

By the 1st century CE, more elaborate mosaic panels were also used to ornament Nymphaea and fountains. The Pompeii mosaics covered walls and entablatures employing the same technique, and these murals frequently resembled real paintings.

Large Mosaic Fountain with theater masks and cascading waterfall in the House of the Large Fountain Pompeii (1st Century BCE – 1st Century CE); Mary Harrsch, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Large Mosaic Fountain with theater masks and cascading waterfall in the House of the Large Fountain Pompeii (1st Century BCE – 1st Century CE); Mary Harrsch, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Older Imperial Roman baths included glass mosaics on their walls and vaults that acted as a mirror of sunlight hitting the pools and gave them a glittering aspect. Both the floors of the mausolea sometimes featured an image of the deceased and the flooring of pools were regularly adorned with mosaics. Beginning in the 4th century CE, mosaics used by the Romans to decorate walls and vaults had an impact on the interior decorators of Christian churches.

The Most Famous Roman Mosaic Artworks

Battle of Centaurs and Wild Beasts mosaic, made for the dining room of Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli (120–130 CE); Altes Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle of Centaurs and Wild Beasts mosaic, made for the dining room of Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli (120–130 CE); Altes Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mosaics of Pompeii

Pliny the Younger’s papers, lost under wreckage until they were found in 1748, contained information about a large volcanic eruption that shook the Bay of Naples. The current analysis has been conducted to precisely alter the traditional date of Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 CE.

Alexander Mosaic, House of the Faun, Pompeii (c. 100 BCE); Berthold Werner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Mosaic, House of the Faun, Pompeii (c. 100 BCE); Berthold Werner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When the volcano erupted, it covered Pompeii and the rest of the Bay of Naples in a thick layer of ash and debris, acting as a protective shield for the people, buildings, and objects at the site. Due to the chemical composition of the volcanic ash and its unique characteristics, archaeologists have discovered nothing short of a perfectly preserved Roman metropolis from the pinnacle of the Roman Empire during the previous 250 years.

The extraordinary preservation and castings of the remains have received a lot of attention, but Pompeii mosaics are just as stunning and deserve their own in-depth discussion.

The Academy of Plato Mosaic

The mosaic at Plato’s Academy has been kept in almost excellent condition. This mosaic, which was created in the 1st century BCE, or right before the eruption, is kept at T. Siminius Stephanus’ residence. The tile shows seven people in a group. Since there is no indication of a distinguishing characteristic of rank, it is exceedingly difficult to precisely identify one of the figures as Plato, even though it is assumed that he is at the top.

Plato’s Academy mosaic from the Villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii (1st Century BCE); Naples National Archaeological Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Plato’s Academy mosaic from the Villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii (1st Century BCE); Naples National Archaeological Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Some academics, including G. W. Elderkin, think that rather than representing a philosophical organization, the seven people in the artwork are a tribute to the Seven Sages of classical Greece. The mosaic’s border features eight different theatrical masks evenly dispersed throughout repeating Roman patterns of bunched fruits and greenery.

By incorporating the theatrical masks on the border with the philosophy-centered accent, the artist may have been attempting to emphasize the wisdom and understanding that philosophy offers.

Cave Canem Mosaic

One of the most intriguing ancient Roman mosaics to a modern audience is the Cave Canem mosaic, also known as Beware of the Dog. The tragic poet’s house’s entrance features a beautifully preserved mosaic. The Latin words CAVE CANEM are inscribed over a picture of an astonishingly realistic dog that is depicted in motion, showing teeth as if it were about to strike, and has a leash and chain around its neck.

The Cave Canem mosaic in the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii (2nd Century BCE); Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Cave Canem mosaic in the House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii (2nd Century BCE); Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It is comparable to any contemporary sign that reads the same thing and is displayed on a fence or door. This is what visitors would have seen as they entered the residence. Among the Pompeii remains is a magnificent cast of a dog caught in the tragedy. Although this dog wasn’t the one in the mosaic, it did have a collar, suggesting that it was probably someone’s pet.

Although there are other mosaics from Pompeii that have survived, these three are among the most fascinating and captivating. Although mosaic installations were a very common type of decoration, we hardly ever see them in this near-perfect state of preservation.

Looking at these mosaics exposes the subjects that were important to the locals’ daily life as well as their aesthetic tastes at the time. Continued excavations at the Pompeii mosaics have turned up more bodies, frescoes, manuscripts, mosaics, allies, and other architectural elements that provide a deeper understanding of daily life in the Roman Empire.

From Antioch to Africa, public buildings and private residences alike frequently featured ancient Roman mosaic art. In addition to being beautiful within itself, Roman mosaic tile art provides a major record of everyday objects like clothing, food, utensils, weaponry, greenery, and animals. Roman mosaic floor artworks also reveal a lot about Roman hobbies, such as gladiator fights, sports, farming, and hunting. On occasion, they even feature the Romans themselves in vivid and lifelike representations.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Most Common Patterns Used in Roman Mosaics?

Although examples of monochrome designs exist, polychrome patterns were the most popular Roman patterns used. Small stones, precious metals like gold, and materials like marble and glass were also occasionally employed as tesserae.

What Are the Sources of a Roman Mosaic Floor?

The Minoans and the Mycenaeans had gravel floors during the Bronze Age. Near East societies employed a similar configuration in the 7th century BCE, but with repeating elements. Pebble flooring was originally attempted in Greece in the 5th century BCE; examples can be seen in Olynthus and Corinth. They were often two-toned, with delicate geometric patterns and straightforward shapes set against a dark background. Pieces of clay or lead, which were regularly used to define shapes in these mosaics, were usually added to strengthen them.

How Is a Roman Mosaic Tile Made?

Roman mosaic art describes patterns created in Rome using tiny white and black tiles. Roman mosaic tiles were primarily square in shape and were made from materials such as glass, pottery, stones, and even seashells. After building a fresh mortar basis, the tiles or tesserae were arranged as closely as possible while any gaps were filled with liquid mortar, a procedure known as grouting. The object was then thoroughly cleaned and polished.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.