Pantheon Rome – World’s Largest Unreinforced Concrete Dome

What is the Pantheon and what was the Pantheon used for? First off, we need to answer the question, “What is a Pantheon?” A Pantheon refers to a type of temple that has been constructed specifically in honor of all the gods. The Pantheon in Rome, Italy is a very special example, due to the Pantheon’s architecture, construction method, and history.

What Is the Pantheon in Rome?

| Architect | Hadrian (76 – 138 CE) |

| Date | 114 CE |

| Function | Temple |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

Exterior view of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; John Samuel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Exterior view of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; John Samuel, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Pantheon in Italy is among the best-preserved Ancient Roman structures, thanks in great part to its continual usage throughout its existence, and the expert use of ancient Roman concrete and engineering for its construction. When was the Pantheon built though and who built the Pantheon? Around 29 BCE, Marcus Agrippa initiated the construction of a complex that would include the Pantheon. In the early days, the Pantheon was used as a private temple complex.

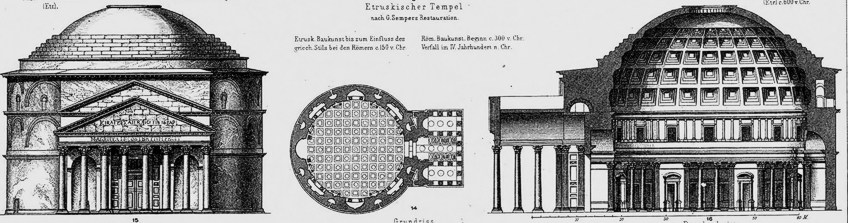

The Layout and Floorplan of the Pantheon, (1885); Meyers Konversationslexikon. Vierte Auflage, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Layout and Floorplan of the Pantheon, (1885); Meyers Konversationslexikon. Vierte Auflage, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The History of the Pantheon in Rome

It was long assumed that the existing structure was erected by Agrippa and later altered, partly due to a Latin inscription on the temple’s facade that reads: “Son of Lucius Marcus Agrippa, made this edifice whilst consul for the third term”. Archaeological investigations, though, have revealed that the Pantheon of Agrippa was entirely demolished, save for the facade. According to some historians, the current building originated in 114 CE, during Trajan’s reign, four years after it was devastated by fire for the second time.

Inscription crediting Lucius Marcus Agrippa with the Construction of the Pantheon in Rome; Remi Jouan, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Inscription crediting Lucius Marcus Agrippa with the Construction of the Pantheon in Rome; Remi Jouan, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ancient History of the Pantheon in Italy

The design of Agrippa’s Pantheon has always been disputed. Due to discoveries in the later years of the 19th century, Rodolfo Lanciani, an archeologist, determined that the initial Pantheon was orientated so that it was facing southward, in comparison with the existing arrangement that faced in a northerly direction and that it featured a shorter T-shaped design with the entry at the foot of the “T”. This definition was frequently used all the way up to the last decades of the 20th century.

Reconstruction of the Pantheon sacred enclosure in the Roman era; Pascal Radigue, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction of the Pantheon sacred enclosure in the Roman era; Pascal Radigue, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

While subsequent archaeological excavations have shown that Agrippa’s structure had a circular shape with a triangular portico and faced northwards, similar to successive constructions, some scholars claim that Lanciani and his team’s results were based solely on conjecture. They argue they identified no new datable material, but they assigned what they discovered to the Agrippan era. They neglected to consider the possibility that Domitian, renowned for his passion for construction and for restoring the Pantheon after 80 CE, was responsible for all they discovered.

The only texts alluding to the Agrippan Pantheon’s adornment reported by an eyewitness are from Pliny the Elder. We learn from him that “the capitals and the pillars were made of Syracusan bronze, which were placed in the Pantheon by M. Agrippa” and that “Agrippa’s Pantheon in Italy has been adorned by Diogenes of Athens, which are gazed upon as masterworks of perfection”. In 80 CE, a fire destroyed the Augustan Pantheon and other structures. Domitian reconstructed the Pantheon after it was again razed in 110 CE. It is unclear how much of the ornamental design should be attributed to Hadrian’s architects.

Bust of Roman emperor Domitianus (antique head on 18th Century body); I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bust of Roman emperor Domitianus (antique head on 18th Century body); I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

They utilized the inscription of the old plaque on the new facade, which was completed by Hadrian but not designated as one of his projects. It is unknown how the structure was used during this period. Hadrian inscribed the Pantheon with the title of the original architect, but the existing inscription cannot be a replica of the original; it gives no indication to who Agrippa’s construction was dedicated, and it is exceedingly doubtful that Agrippa would have portrayed himself as “consul tertium” in 25 CE, as it was the title usually given to people after they had passed away. Whatever the reason for the modification in the plaque, the new text demonstrates the fact that the building’s function had changed.

Medieval History of the Pantheon in Italy

Pope Boniface IV obtained the temple from Byzantine emperor Phocas in 609 CE and then had it converted into a Christian church and dedicated it on the 13th of May, 609 CE to St. Mary and the Martyrs. It is said that 28 cartloads of holy martyrs’ remains were taken from the tombs and put in a porphyry basin under the high altar. Boniface inserted a statue of the Virgin within the new church after it was dedicated. The building’s conversion to a church spared it from the neglect, ruin, and theft that struck most of ancient Rome’s structures during the early medieval era. Yet, Emperor Constans II, who toured Rome in July 663 CE, spoliated the structure, according to Paul the Deacon:

During his 12-day stay in Rome, he tore down anything that had been constructed of metal in the ancient era for the adornment of the city, to the degree that he even removed the church’s roof, which was once known as the Pantheon and had been established in honor of all the divine beings and was now a church, by the authorization of the rulers; and he removed the bronze tiles and started sending them with all the other decorations to Constantinople.

Coin featuring Constans II (between c. 651 -654); Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Coin featuring Constans II (between c. 651 -654); Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Over the centuries, much of the excellent exterior marble has been taken; for instance, capitals from several of the pilasters may be found at the British Museum. Two columns were taken and disappeared from the medieval structures that adjoin the Pantheon to the east. The bronze roof of the portico was dismantled in the early 17th century, and the medieval campanile was substituted with the renowned twin towers (sometimes incorrectly credited to Bernini), which were not demolished until the late 19th century. The exterior sculptures that ornamented the portico above Agrippa’s inscription were the only other loss. The marble interior has been mostly preserved, but with substantial renovation.

The Renaissance History of the Pantheon in Rome

Several noteworthy interments have taken place in the Pantheon since the Renaissance. The artists Annibale Carracci and Raphael, the architect Baldassare Peruzzi, and the musician Arcangelo Corelli are all buried there. The Pantheon was embellished with artworks in the 15th century, the most famous of which being Melozzo da Forl’s Annunciation (c. 1466). The Pantheon served as inspiration for several architects, including Filippo Brunelleschi.

An 1836 view of the Pantheon by Jakob Alt, showing the twin bell towers, in place from early 17th to late 19th centuries, that were added by Pope Urban VIII; Jakob Alt, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

An 1836 view of the Pantheon by Jakob Alt, showing the twin bell towers, in place from early 17th to late 19th centuries, that were added by Pope Urban VIII; Jakob Alt, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The portico of the Pantheon’s bronze ceiling was ordered to be melted down by Pope Urban VIII. The majority of the bronze was used to create reinforcements for the Castel Sant’Angelo fortress, with the remainder being utilized by the Apostolic Camera for various projects. It is also stated that Bernini used the bronze to create his renowned baldachin for St. Peter’s Basilica’s high altar, but according to at least one scholar, the Pope’s records say that around 90% of the bronze was utilized for the cannon and the rest arrived from Venice. The long frieze under the dome, with its fake windows, was “restored” in 1747, but exhibited little similarity to the original.

The Pantheon in the Modern Era

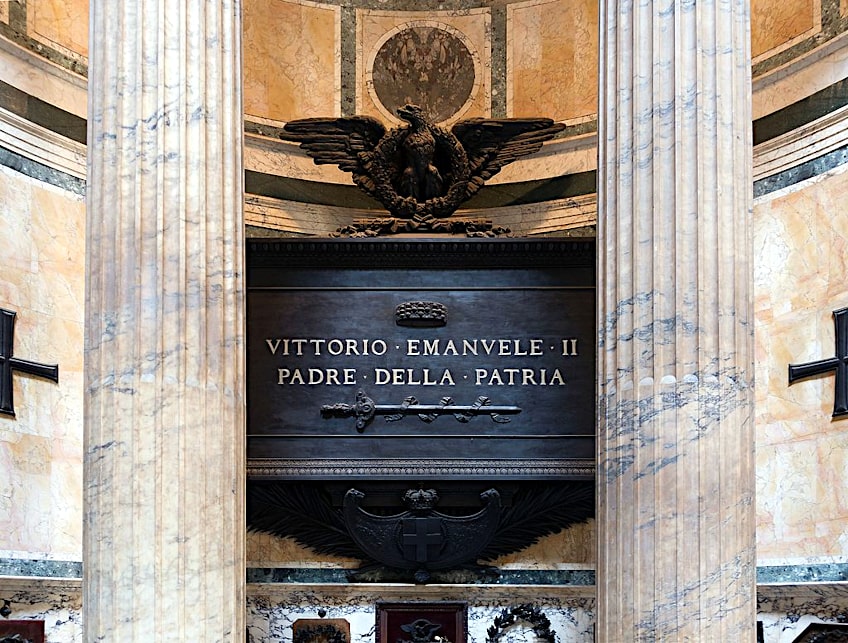

In the early 20th century, a section of the original was restored in one of the panels, as much as it could be recreated from Renaissance sketches and artworks. The Pantheon contains the tombs of two kings of Italy: Umberto I and Vittorio Emanuele II. It was meant to be the ultimate resting place for the kings of the House of Savoy; however, monarch rule had been abolished in 1946, and the government denied the burial of previous monarchs who had perished in exile. The Pantheon in Italy is currently utilized as a Catholic church. On holy days and Sundays, masses are held there, and weddings are also hosted there occasionally.

The Pantheon Architecture

What was the Pantheon made of? The Pantheon’s structure was achieved through the combination of an ancient type of concrete invented and perfected by the Romans and brick. Originally, the structure was accessed through a flight of stairs. Later development increased the ground level rising to the portico, and removed these stairs. Relief sculptures, most likely gilded with bronze, adorned the pediment. Holes in the pediment which held the carvings have created an outline indicating that the artwork was likely designed as an eagle inside a wreath, with streamers extending from the wreath to the sides.

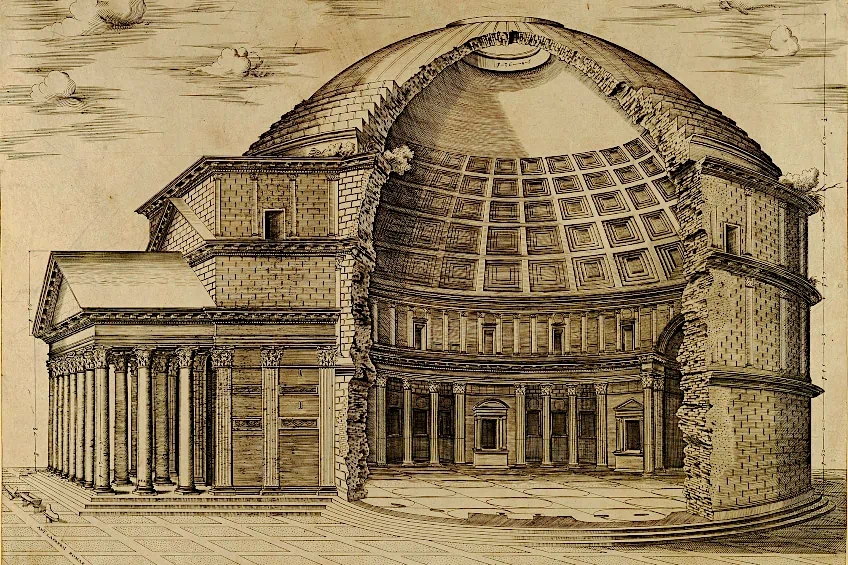

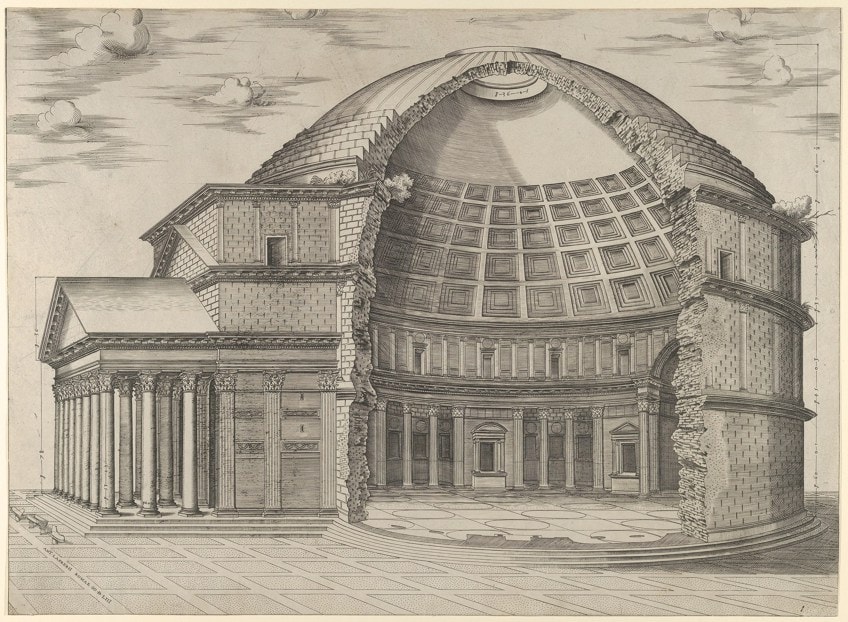

Image showing the internal structure of the Pantheon (1553); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Image showing the internal structure of the Pantheon (1553); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Portico

The ruins of a second pediment on the intermediary block between the rotunda and the portico reveal that the extant portico is significantly shorter than originally envisaged. A portico oriented with the second pediment would accommodate columns with shafts nearly 15 meters tall and capitals about 3 meters tall. In comparison, the current portico has shafts nearly 12 meters tall and capitals 2.5 meters tall. Some academics have tried to explain the architectural changes by claiming that after the taller pediment was built, the requisite columns didn’t arrive – maybe due to logistical issues.

The exterior portico of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; Keanu Dölle, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The exterior portico of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; Keanu Dölle, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Columns

To fit the shorter pediments and columns, the builders had to make some unusual adaptations. Others have pointed out that even if the higher columns had been supplied, fundamental structural restrictions might have prohibited them from being used. Presuming that every column would be arranged on the ground next to its pediment prior to actually being pivoted upright, there would have been a column-length area necessary on one side of the pediment for the ropes and swiveling equipment, and at least a column-length area needed for the opposite side.

The columns and interior of the portico of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, PDM-owner, via Wikimedia Commons

The columns and interior of the portico of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, PDM-owner, via Wikimedia Commons

The installation of the necessary 50-foot columns could not be planned without tying itself in an impossible knot. Irrespective of sequence, the shafts were just too long to be placed on the floor in a usable form. The main body of the structure would hinder the inner row of columns, and in the latter stages of building, some previously erected columns would eventually prevent the erection of new columns. It has also been suggested that the portico’s size was connected to the urban planning of the area in front of the Pantheon.

Granite columns for the structure’s pronaos were mined at Mons Claudianus in the east of Egypt. From the quarry, placed on wooden sleds, they were hauled more than 100 kilometers to the river. They were transported down the Nile by barges during the spring flood, then moved to boats to traverse the Mediterranean Sea to the port of Ostia. They were then loaded back onto boats and towed up the Tiber River towards Rome. The Pantheon was still around 700 meters away after being delivered close to the Mausoleum of Augustus. As a result, they had to be dragged or moved on rollers to the building site.

Sculptures and Doors

There were two massive niches in the Pantheon’s portico walls, possibly intended for sculptures of Agrippa and Augustus Caesar. The cella’s huge bronze doors are known to be the oldest yet discovered in Rome. These were believed to be a 15th-century substitute for the original, mostly because later architects thought they were too tiny for the door frames. Despite restoration and the insertion of Christian symbols throughout the centuries, further research of the fusion method showed that they are genuine Roman doors, a rare specimen of Roman monumental bronze remaining.

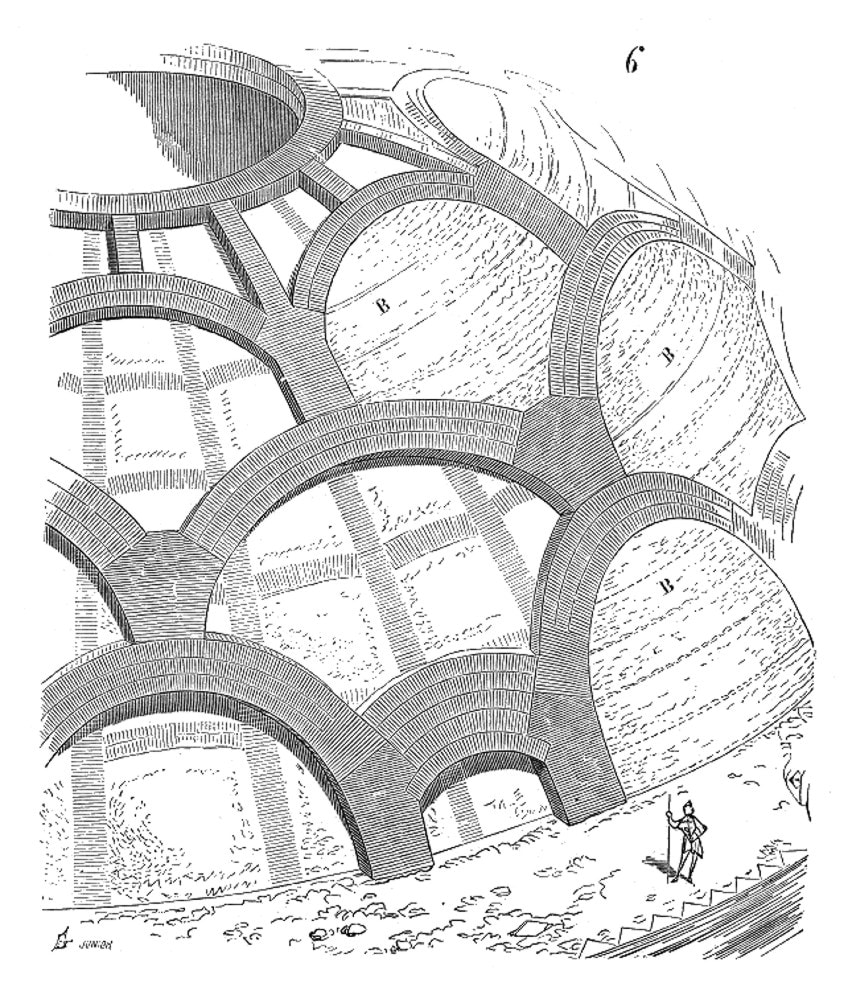

Rotunda

The dome’s thickness ranges from 6.5 meters at the base to 1.2 meters near the oculus. The materials utilized in the dome’s concrete also differ. The material is travertine at its widest point, followed by terracotta tiles, and finally, at the highest point, pumice and tufa, both porous lightweight stones. The oculus softens the strain at the top, where domes are usually the weakest and most prone to collapse. The use of gradually less compact aggregate stones, such as little pots or bits of pumice, in upper levels of the dome was shown to significantly lower dome tensions.

View of the interior of the dome and oculus of the Pantheon in Rome; Sonse, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

View of the interior of the dome and oculus of the Pantheon in Rome; Sonse, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The pressures in the arch would have been 80% higher if regular-weight concrete had been utilized throughout. A complicated structural element is formed by hidden chambers created within the rotunda. This helped lower the roof’s weight, as did removing the apex from the oculus. A sequence of brick relief arches, observable from the outside and incorporated into the bulk of the brickwork, adorn the peak of the rotunda walls. There are relief arches above the niches inside the Pantheon, for instance, but all of these were disguised by marble faces on the interior and maybe by stucco on the outside.

Illustration of the engineering of the Roman Pantheon’s dome (c. 1856); Eugène Viollet le Duc, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration of the engineering of the Roman Pantheon’s dome (c. 1856); Eugène Viollet le Duc, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The largest unreinforced dome in the world made from concrete continues to be the Pantheon in Rome and it is substantially larger than earlier domes. It is the only masonry dome that does not need to be reinforced. To avoid collapse, all other remaining ancient domes were either constructed with tie-rods, chains, and bands or were modified with similar devices. Despite being depicted as a free-standing structure, it was abutted in the back by another structure.

Interior

Visitors are greeted upon entering by a huge spherical chamber covered by the dome. The top of the dome’s oculus was never covered, enabling rain to pour through the roof and onto the flooring. As a result, the inside floor is fitted with drains and has been created with a 30-centimeter inclination to encourage water drainage. The inside of the dome may have been designed to represent the arching vault of the sky. The only natural light sources in the interior are the oculus at the dome’s peak and the entry door.

Modern photograph of the interior of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; This Photo was taken by Andrea Bertozzi. Feel free to use my photos, but please mention me as the author and send me a message., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Modern photograph of the interior of the Pantheon in Rome, Italy; This Photo was taken by Andrea Bertozzi. Feel free to use my photos, but please mention me as the author and send me a message., CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Light from the oculus flows around this area during the day, creating a sundial effect in reverse: recording time with lighting instead of shadows. The dome has sunken panels arranged in five rings of 28. It is assumed that this uniformly spaced arrangement has symbolic value, either numerical, lunar, or geometric. The coffers may have had brass rosettes representing the celestial firmament in antiquity. The interior design’s unifying element is squares and circles.

Painting showing the light from the oculus in the interior of the Pantheon by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1747); Giovanni Paolo Panini, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Painting showing the light from the oculus in the interior of the Pantheon by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1747); Giovanni Paolo Panini, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The checkerboard flooring juxtaposes with the dome’s concentric rings of squared coffers. Each interior region, from the ceiling to the floor, is partitioned using a separate method. As a result, the interior ornamental zones are out of place. Although the cylindrical space capped by a hemispherical dome is intrinsically confusing, the overall result is quite spectacular. This design was not always welcomed, and the attic level was restored in the 18th century to the Neoclassical style.

Catholic Art and Additions

Pope Clement instructed Alessandro Specchi to design the current apses and high altar. When the Pantheon was dedicated to Christian worship on the 13th of May, 609CE, Phocas presented Pope Boniface IV with a figure of the Virgin and Child from the 7th-century Byzantine period that was displayed above the high altar. Luigi Poletti designed the choir, which was added in 1840. The first niche to the side of the entry features an anonymous artist’s sculpture St Nicholas of Bari (1686).

Portrait of Pope Boniface IV by Giovanni Battista Cavalieri (1580); Giovanni Battista de’Cavalieri, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Pope Boniface IV by Giovanni Battista Cavalieri (1580); Giovanni Battista de’Cavalieri, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The tomb of King Victor Emmanuel II may be seen in the second chapel. To choose which architect should produce it, a contest was launched. Giuseppe Sacconi took part but lost; he would subsequently design Umberto I’s grave in the opposite church. Manfredo Manfredi was the winner of the competition and began working in 1885. The monument is topped with a massive bronze plate depicting the arms of the House of Savoy. Victor Emmanuel III, who died in exile in 1947, is commemorated by the golden lamp over the monument.

The tomb of Victor-Emmanuel II, king of Italy. Pantheon, Rome, Italy; Jebulon, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The tomb of Victor-Emmanuel II, king of Italy. Pantheon, Rome, Italy; Jebulon, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

An anonymous artist painted Emperor Phocas presenting the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV which is dated to around 1750 on the right wall. There are three commemorative plaques on the flooring, one of which commemorates a Gismonda in vernacular. Bernardino Cametti’s statue of St. Anastasius (1725) fills the last niche on the right-hand side. To sustain worship in the chapel, Desiderio da Segni, a 16th-century canon, established the first chapel on the left as the chapel of a confraternity of musicians and artists. Jacopo Meneghino, Antonio da Sangallo Junior, Zuccari, Giovanni Mangone, and Flaminio Vacca were some of the founding members. Cortona, Bernini, Algardi, and many other prominent architects and painters from Rome continued to join the confraternity as it attracted more aristocratic members.

In the adjoining chapel lies the grave of King Umberto I and his wife Margherita di Savoia. Initially dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel, the chapel was later renamed St. Thomas the Apostle. Giuseppe Sacconi created the current design, which was finished after his death by his disciple Guido Cirilli. The tomb is made up of an alabaster slab plated in gilded metal. Munificence, by Arnaldo Zocchi, and Generosity, by Eugenio Maccagnani, are allegorical depictions on the frieze. The National Institute of Honor Guards to the Royal Tombs, formed in 1878, looks after the royal tombs. Cirilli designed the altar with royal arms. The third niche houses the relics of the famous artist Raphael.

Bust of Raphael in the Pantheon by Giuseppe Fabris (1833); Jastrow, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bust of Raphael in the Pantheon by Giuseppe Fabris (1833); Jastrow, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Raphael’s fiancée is buried to the right of his tomb; she passed before they could marry. The tomb was provided by Pope Gregory XVI, and its plaque reads “Here lays Raphael, by whom the divine mother of all things dreaded to be conquered while he was alive, and when he was dying, herself to perish”. Pietro Bembo composed the epigraph. Antonio Muoz created the current configuration in 1811. Giuseppe Fabris created Raphael’s bust in 1833. Annibale Carracci and Maria Bibbiena are remembered by the two plaques. Behind the tomb stands the Madonna of the Rock, so titled because she has one foot on a boulder. Raphael requested it, and Lorenzetto completed it in 1524.

Tomb of Raphael in the Pantheon with Madonna of the Rock by Lorenzetto (1524); Francesco Gasparetti from Senigallia, Italy, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Tomb of Raphael in the Pantheon with Madonna of the Rock by Lorenzetto (1524); Francesco Gasparetti from Senigallia, Italy, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The niches in the Chapel of the Crucifixion reveal the Roman brick wall. The altar’s wood crucifix dates to the 15th century. Descent of the Holy Ghost (1790) by Pietro Labruzi is shown on the left wall. The Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen’s low relief depicting Cardinal Consalvi presenting Pope Pius VII with the five provinces that had been returned to the Holy See in 1824 may be seen on the right. Agostino Rivarola, the cardinal, is shown on the bust. Francesco Moderati’s 1727 statue of St. Evasius is located in the last niche on this side.

Etymology

What is a Pantheon? The word “Pantheon” derives from the Greek word Pantheion, which means “all (pan) the gods (theios).” A Roman senator named Cassius Dio, who wrote in Greek, hypothesized that the name of the structure is either derived from the numerous deity statues erected around it or from the dome’s similarity to the skies. His ambiguity strongly implies that “Pantheon” was only the building’s colloquial name and not its official one. In actuality, the idea of a pantheon that is devoted to all the gods is dubious. Even though it is only referenced in a source from the 6th century, Antioch in Syria was home to the only pantheon that was clearly recorded prior to Agrippa’s. Altars designed to receive offering to “all the gods” (usually a set of twelve) were common in Ancient Greek sanctuaries though.

Roman altar featuring depictions of twelve gods each identified by an attribute (1st Century CE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman altar featuring depictions of twelve gods each identified by an attribute (1st Century CE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ziegler made an effort to compile documentation of pantheons, but the majority of the names on his list are just basic dedications to “all the gods” which are not necessarily actual pantheons in the form of a temple containing a cult that truly venerates all the divinities. As opposed to other temples, Hadrian’s Pantheon is never described by ancient writers using the word Aedes, and the Severan inscription engraved on the architrave uses “Pantheum” rather than “temple of all the gods.” Dio omits to include the most straightforward justification for the name—that the Pantheon was built in honor of all the gods.

Interior view of the Pantheon by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (c. 1748-1774); Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Interior view of the Pantheon by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (c. 1748-1774); Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

According to Livy, it had been decided that temple structures (or possibly temple cellae) should only be devoted to one divinity to clarify who would be insulted if, for instance, the building were hit by lightning, and since it was only proper to give sacrifice to a particular god. According to some historians, the term Pantheon “may have meant other things, it need not refer to a specific set of gods or even all the gods”. The term “pantheos” may undoubtedly refer to certain deities. Additionally, keep in mind that the Greek term does not always imply “of a god”, but might instead indicate “superhuman” or even “great”. The general name “pantheon” has occasionally been used to refer to various places in which famous deceased are honored or interred when the Parisian church of Sainte-Geneviève was deconsecrated and transformed into the secular monument known as the Panthéon of Paris.

One of the most recognizable Roman buildings in the heart of Rome is the Pantheon. Marcus Agrippa gave the decree for the Pantheon in Rome to begin construction in 27 BCE. It is one of the few remaining structures from the ancient Rome era. After Agrippa’s structure was devastated by a significant fire in 80 CE and then again in 110 when it was hit by lightning, the present temple and its distinguishing round dome were not constructed until the 2nd century, under the reign of the emperor Hadrian. The bronze writing “Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, erected this temple” is seen on the facade. It’s interesting to note that this text was inserted under the reign of Hadrian.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Pantheon in Italy?

Amazingly, so many people today are unaware of the Pantheon’s initial use. The word Pantheon, which referred to a temple that was devoted to all gods, is Greek in origin. The Roman Pantheon was not utilized as a church until pope Boniface IV received it from emperor Phocas in 608 CE. Over time, a growing number of altars and tomb markers were added, including those for the famed artist Raphael and several Italian rulers. The seven niches that encircle the center area contain these burials.

What Is a Pantheon?

A building dedicated to all the deities is known as a Pantheon. Ancient Greeks and Roman did not worship their gods inside of their temples but in the sacred precinct around the temple. The actual temple structure was considered to be the home of the deity where sacred statues and gifts presented to the god were kept. Usually only priests and temple attendants entered temples to perform certain prescribed duties, meaning that the interior decoration of the temple was not meant to impress worshippers, but the gods themselves. The Pantheon in Rome is unusual in that the altars to the gods were located inside the rotunda. The Pantheon in Rome is the most well-known example of a temple dedicated to (and therefore a home to) all the Roman gods. The term pantheon can also relate to a group of important or respected individuals.

Around When Was the Pantheon Built?

The Pantheon, which was constructed between 113 and 128 CE, has both its own distinctive architectural traits and those that were fashionable at the time. Greek architecture is adopted for the porch and the middle block, with an entablature supported by 16 columns. The dome’s complete exterior as well as the coffered ceiling’s interior would have been coated with bronze when it was initially constructed. Some of the bronze was taken out in order to create the 80 guns at Hadrian’s mausoleum, Castel Sant’Angelo, but it was later recovered when it was melted down for Vittorio Emanuele II’s tomb, which is currently housed in the Pantheon. The Goths stole additional bronze from the city.

What Was the Pantheon Used for During the Years?

It is thought to have originally been a temple dedicated to the various Roman deities. In the year 330 CE, Emperor Constantine relocated the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to Byzantium. After than, the Pantheon in Italy experienced a protracted period of decay. The Western part of the Roman Empire, which included Rome, was subjugated by the German warrior Odoacer in 476 CE. The long-term deterioration of the Pantheon continued. The Pantheon was then transformed into a Christian church known as St. Mary and the Martyrs in 609 CE when Pope Boniface IV got approval from Byzantine emperor Phocas. It is known to be the very first pagan temple in Rome to be transformed into a church for the worship of Christianity. Due to the papacy’s ability to repair and maintain it, the conversion was crucial to the Pantheon’s survival into the modern period.

Who Built the Pantheon in Rome?

According to Roman history, the original Pantheon was constructed there and dedicated to Romulus, its mythical creator, following his ascension to heaven. According to the majority of historians, Agrippa, Emperor Augustus’ right-hand man, constructed the first Pantheon around 27 BCE. Emperor Domitian restored it after it was destroyed in the great fire of 80 CE, but it was hit by lightning and burned once again in 110 CE. Emperor Hadrian, who had a love for building, constructed the Pantheon in 120 CE. He collaborated on its design with Apollodorus of Damascus, a well-known Greek architect of the time who was sadly put to death on the emperor’s orders after a disagreement over the temple’s design.

What Was the Pantheon Made Of?

Bricks, limestone, and other materials are combined with mortar and tiny stones to create the concrete. They employed lighter materials higher up the building because of the substantial material weight. Concrete mixed with scoria and tufa was used to create the dome.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.