Battle of Agincourt – The Turning Point in the Hundred Years’ War

During the medieval period, spanning between 1337 AD – 1453 AD, feudal England and neighboring France were locked in the long discontinuous conflict we now know as the Hundred Years’ War. One particularly decisive victory to have occurred during this time was claimed by the English; fought on muddy French soil near the town of Agincourt where King Henry V, who himself rode into battle, would lead his troops to victory despite the immense numerical inferiority of their numbers. This was a turning point in history not only because of the brave heroism of the young king and his soldiers, but because it would also influence the evolution of medieval warfare and tactics during this period – especially those pertaining to ranged combat. If you are interested in learning more about this iconic footnote in Medieval history, please continue reading. Join us as we discuss and dissect the events of the battle itself, what led up to it, and what its consequences were.

The Significance of the Battle of Agincourt

Without key successes such as in Agincourt, England’s soon thereafter victorious conquest of Normandy and the eventual Treaty of Troyes (1420) – the latter of which saw King Henry V become heir to the French Crown – may not have been possible. But when was the Battle of Agincourt fought?

The battle itself occurred on the 25th of October, in the year 1415, and was a bloody mess of a brawl lasting no more than two hours despite the cost of over 6600 lives across both sides.

| Name of the Battle | The Battle of Agincourt |

| Overarching Conflict | The Hundred Years’ War |

| Date | 25th of October 1415 |

| Location | Agincourt, France |

| Combatants | England versus France |

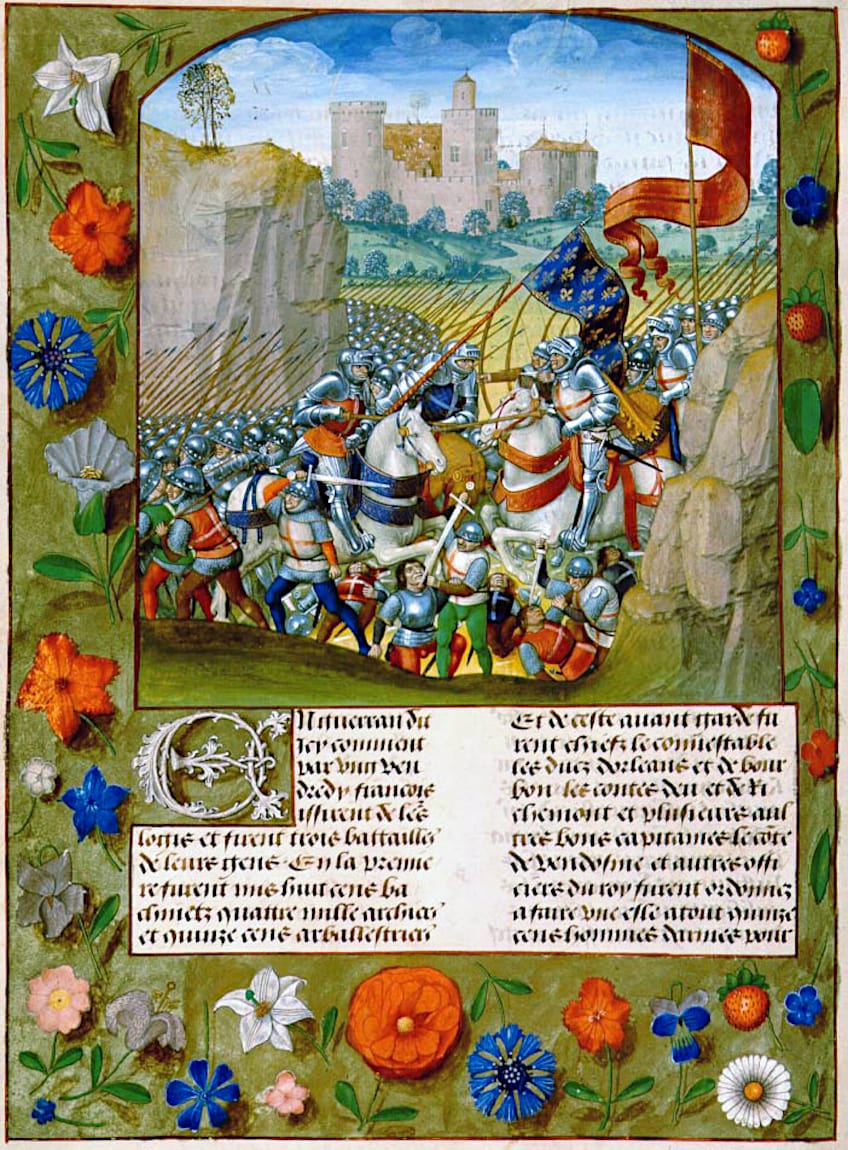

The Battle of Agincourt from Enguerrand de Monstrelet, Chronique de France (c. 1495); Enguerrand de Monstrelet, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Battle of Agincourt from Enguerrand de Monstrelet, Chronique de France (c. 1495); Enguerrand de Monstrelet, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Hundred Years’ War and the Rise of King Henry V

Beginning in 1337, the War was fought intermittently for a little over a full century. It featured political clashes, sieges, and open-field battles – all of which were hosted on French soil – and ended only in 1453 as the English-occupied city of Bordeaux capitulated to France who eventually reclaimed all but Calais back from the English.

Besides the land it occupied within the Kingdom of France, England also maintained that its nobility held a legitimate claim to the French Crown since King Edward III was the son of King Charles IV’s sister, Queen Isabella of Valois, and it was these grounds upon which contention between the two nations was built.

Miniature depicting King Edward III granting his son Edward of Woodstock (the Black Prince) the principality of Aquitaine in Southern France (between 1386 and 1399); British Library, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Miniature depicting King Edward III granting his son Edward of Woodstock (the Black Prince) the principality of Aquitaine in Southern France (between 1386 and 1399); British Library, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

It was King Edward III who, in 1337, would cast the first stone and initiate a decades-long conflict by claiming titleship of the French Crown in spite of King Philip VI’s succession. Blood was first drawn in Flanders where Edward III sought to contest the legitimacy of Philip VI’s reign with steel and arrows.

The Motives of Henry V

By 1356, both the Battles of Crecy (1346) and of Poitiers (1356) saw the English claiming large ribbons of land in French territory. However, due to sovereign disputes back home, an absence of sufficient initiative and resolve, and the legacy of the Black Plague, the English had lost dominion over all but three measly port towns along the north and southwest coasts of France.

By the time King Henry V ascended the English throne in 1413, political tensions within his kingdom and the legacy of its diminished gains in France would spur the young King’s interest in sailing across the narrow arm of the English Channel to reclaim what territories had been repossessed by the French some few years prior.

Portrait of Henry V The King of England by an unknown artist (16th Century); National Portrait Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait of Henry V The King of England by an unknown artist (16th Century); National Portrait Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

To the young king, territorial gains in France would put to rest the discordance and cloaked daggers that surrounded his House following his father’s usurpation of the English Crown from the clutches of Richard II at the turn of the 15th century.

An important bit of context to note here is that, at the time, the two rivaling nations were formally engaged in a truce pact, which was consummated through the marriage of King Richard II to Catherine Valois, the daughter of Charles VI. Meant to last 28 years, it would take only 17 for Henry V to decide that the sword was indeed mightier than the pen. Along with the political instability in France brewing on account of Charles VI’s infamous descent into madness, it seemed to Henry almost the perfect time to effectuate his strategy.

Miniature depicting King Charles VI in coronation costume (15th Century); Jean Perréal, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Miniature depicting King Charles VI in coronation costume (15th Century); Jean Perréal, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

An Immodest Proposal

Before the King’s warships were mustered, however, he sent a missive to France demanding that Aquitaine be returned to English control, the remaining 1 600 000 crowns in ransom fare for King John II, the hand of Catherine Valois in marriage, and a dowry of 2 000 000 crowns. The sum total of 3 600 000 crowns beseeched by Henry V would amount to roughly $550 000 000 in today’s time. Understandably offended by his request, the French heeded his words but offered them little credence. What was instead offered was a dowry of only 600 000 crowns and titleship to an increased width of Aquitaine’s borders.

With ambitions of solidifying his disputed sovereignty back home and reconsolidating England’s grip on French land, Henry V then sailed to Normandy where he arrived in August of 1415 with between 11 000 to 12 000 soldiers in tow.

The Siege of Harfleur

An armada of about 700 English ships sailed southward on the 11th of August with King Henry and his closest advisors aboard its flagship, arriving at the French shoreline three days later within eyeshot of the town of Chef-de-Caux (modern-day Sainte-Adresse), along the mouth of the River Seine. Shortly after disembarkation, Henry V wasted no time in rallying his army toward the fortified port city of Harfleur.

English gold Noble (coin) struck during the reign of Henry V depicting the king on a ship (1413); Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

English gold Noble (coin) struck during the reign of Henry V depicting the king on a ship (1413); Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The strategic advantage of capturing Harfleur was twofold. On the one hand, claiming such a key port would assist the war effort by allowing for the establishment of an operational base and secure supply route to assist with future infiltrations into France. On the other, apprehending this region from the French would also remove a long-embedded thorn from the hide of England whose southern coastlines saw frequent French incursions originating from Harfleur.

Arrival of the English Army

After three days of sailing, Henry V’s fleet would dock upon the shores of Normandy and begin preparations for the forthcoming siege. The English Army would have a fighting force of approximately 2300 men-at-arms, 9000 bowmen, as many as 12 gunpowder cannons, and several siege towers. Although the population of Harfleur was composed of only about 5000 denizens, merely 250 of whom formed part of its garrison of fighting men, both the town itself and its port were strongly fortified behind 14.7 ft-thick walls adorned with no fewer than 24 towers.

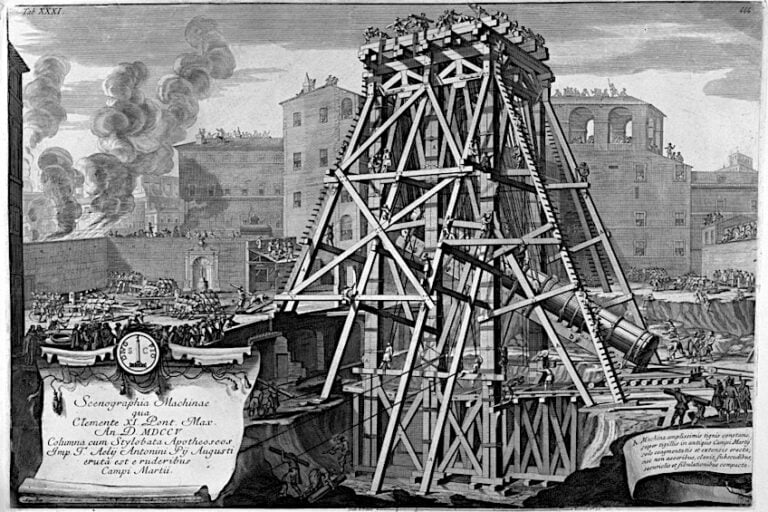

Miniature depicting the Siege of Harfleur from the Vigils of Charles VII (c. 1484); Martial d’Auvergne, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Miniature depicting the Siege of Harfleur from the Vigils of Charles VII (c. 1484); Martial d’Auvergne, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Between the King and his wartime advisors, it was deemed prudent to form a blockade surrounding the town to prevent the arrival of supplies and French reinforcements. As was the case most often during the many sieges of the medieval period, the idea was to win Harfleur through attrition if steel proved fruitless. Lord Thomas, the Duke of Clarence and King Henry V’s younger brother, rode eastward with several regiments to prevent the arrival of French support arriving from inland. The primary battalion would remain with Henry V, who would push his guns and siege towers from the northern shore until they reached within striking distance of the walls.

Before swords were drawn, however, Henry V sent forth a missive to the townsmen of Harfleur, insisting they surrender. In this message he detailed how his claim to the French throne allowed him the biblical right to execute all the town’s inhabitants should he need to take it by force, the idea behind which was to inculcate fear amongst the populace. This would, however, prove an ineffective tactic as a relief retinue of over 300 highly trained French soldiers led by the legendary Raoul de Gaucourt would slip into the town’s gates despite Thomas’s landward approach. The timely arrival of these servicemen would be enough to convince the people of Harfleur that they indeed had a fighting chance against the invaders. The French decided then to shut the town’s sluice gates, flooding the northeastern valley to make it tougher for Henry V’s army to coordinate a circumjacent assault. Thus, the invading Englishmen had no other choice but to engage their foes in combat.

Capitulation at Great Cost

For King Henry V’s bowmen and gunners to be within striking distance of the town’s walls, they had to lay themselves within range of the archers, cannons, and trebuchets who retorted stiffly and undeterred from the bulwarks above their heads. Despite English cannon fire raining death as deep in as the center of the town proper, the French pressed their defense tirelessly, inflicting heavy losses on Henry’s irreplaceable soldiers. To make matters worse, the arrival of September’s summer heat saw to it that the inundated northeastern valley became a stagnant, marshy bog wherein all sorts of bacteria and diseases began to muster. It was not too long thereafter that cases of dysentery spread among the English ranks.

Medieval English cannon being fired by historical re-enactors; Stephen McKay / Cannon Firing, Whitby Abbey

Medieval English cannon being fired by historical re-enactors; Stephen McKay / Cannon Firing, Whitby Abbey

Following subsequent failed attempts at tunneling beneath the walls of Harfleur and a sortie led by Gaucourt that saw to the immolation of a siege tower, the English King grew desperate enough to press the entire might of his army against the bulwarks of the town’s primary thoroughfare. The French fought ferociously but were soon overwhelmed and forced to retreat inward as the English assumed control of the gate. After several days of constant bombardment from Henry V’s guns, the ever-looming promise of execution in the event of defeat without capitulation and the unlikely arrival of timely reinforcements were enough to crush the fighting spirit of the French who officially surrendered Harfleur to the English on the 22nd of September.

Within a month and a half, Henry V’s army had won the city over. Its capitulation, however, came at a heavy cost. His fighting force had been reduced by nearly a third of its initial manpower, either by death or injury from both combat and illness alike. For the English, over 3000 bowmen and 1000 men-at-arms met their ends at the siege of Harfleur, which would be a substantial blow to Henry V’s idealized plans of conquest in France.

A Change of Plans

With approximately 7100 soldiers remaining, Henry V had no other choice but to shift his strategy away from conquering the towns and forts of Northern France. The initial plan was to subjugate and tax the region to pay off the vast sums of borrowed gold that had been required to muster his invasion force. With such goals now impossible to achieve, Henry V had no other choice but to project a new plan of action.

War Council

He was advised by his council to cut short the campaign and leave a garrison behind at Harfleur so that his army might return home to recover and bolster, a suggestion that the King most stubbornly rejected. He knew that the victory over Harfleur was not nearly enough to solidify his contested authority as King back home nor remunerate the loans demanded of the crusade.

Henry decided to disregard the concerns of his advisors, garrisoning Harfleur with 900 bowmen and 300 men-at-arms before initiating a mounted push towards the English-occupied port town of Calais with 5000 archers and 900 men-at-arms.

The Routing of the English Army

Despite his advisors deeming it most prudent to sail towards Calais since it and Harfleur shared the same coastline, the obstinate King insisted on traveling inland so that he may display further proof of his might by pillaging the French countryside with impunity. This, however, gave French constable Charles d’Albret in neighboring Rouen the opportunity to intercept Henry V and his men west of the River Somme while additional French troops guarded the crossing from the east. This effectively routed the English army off course as they were forced to redirect to avoid being surrounded from all sides.

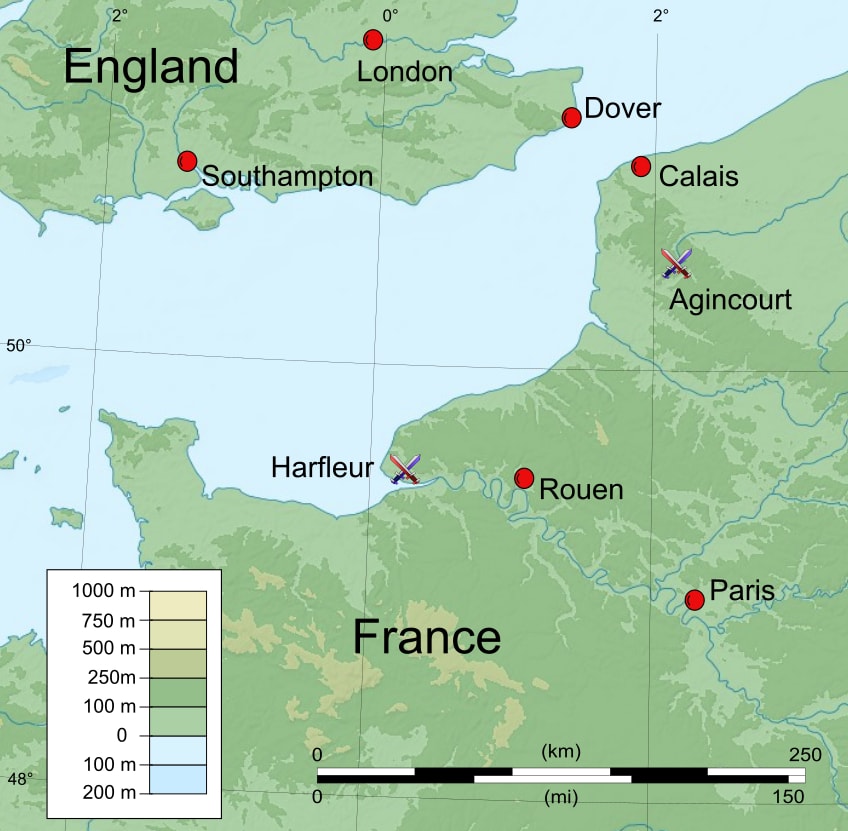

Places featured in Henry V’s campaign of 1415-16; Amitchell125, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Places featured in Henry V’s campaign of 1415-16; Amitchell125, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

All the while, Constable Charles mobilized his own horde of troops towards the flat planes of Peronne along the river where he expected the English to eventually arrive. As the invaders traversed along the river, sorties of French troops were dispatched to engage the column of marching Englishmen, softening their numbers and resolve even further.

However, much to the surprise of the French, Henry V drew his men south-eastward away from the river, thus avoiding Charles’ intended interception. Historians believe that the decision was made after capturing French soldiers involved in these guerrilla sorties and interrogating the information from them. 11 days after their march first commenced, the English finally discovered a shallow river crossing unguarded by the French, allowing them safe passage across the Somme.

The Inevitability of Battle

However, what was meant to be a swift 230 km march toward Calais became a trudge nearly double the distance. Tired and starved as they were, King Henry V and his men were dismayed by the news brought from their onward scouts who informed them of a French legion gathered near the castle of Agincourt, between them and Calais. Having heard of Henry V’s safe crossing of the Somme on the same day as it occurred, Charles had ridden his troops with haste to once again intercept the English column, though this time with success. Furthermore, the lengthy meander of the English had given the French more than enough time to amass a much larger fighting force. A battle was at this point unavoidable and the English army seemed in no fit state to compete.

The Battle of Agincourt

With only 30 miles remaining of their journey to the safety of Calais’ walls, what now stood before the English army was a horde of French troops roughly double in number. Along the eastern valley two miles out stood around 3000 bowmen, 6000 men-at-arms, and 3000 infantrymen ready to rid their homeland of the invaders. With neither side eager to make the first move, both armies set up camp for the night.

As the sun began to recede, the French camp was littered with firelight and the sounds of laughter and party could be heard all the way from the English ranks whose leader had demanded silence and vigilance throughout the night. During this time, as rain began pelting the backs of his weary soldiers, King Henry V took the time to walk amongst his men and issue words of encouragement. There was no doubt in his mind or anyone else’s, however, that they would die the following day.

What Happened on the Battlefield?

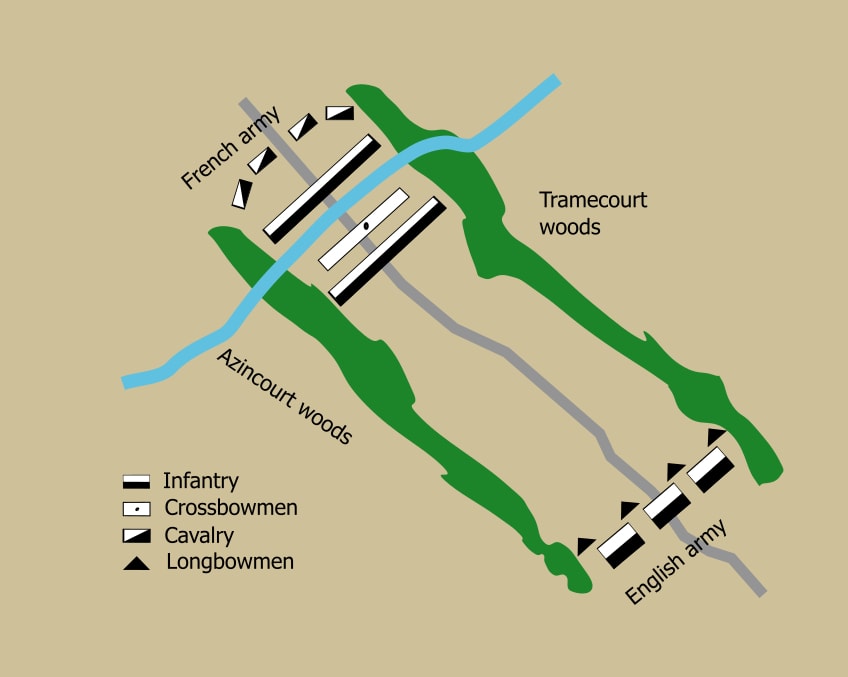

Come morning, Henry V would march his men into position before the break of dawn while the French would only do so as the sun rose. As its rays cast down upon the battlefield, though, Henry V’s keen eyes caught sight of a golden opportunity: the night’s rainfall had turned the sewn farmland to sticky clay, a terrain that would impede any advance of infantrymen or cavalry. With this in mind, Henry V would arrange his men-at-arms in three adjacent defensive lines with two clusters of archers between each rank and flanked on either side with two larger concave groups of longbowmen whose reach surpassed that of the French.

Battle formations of the French and English at Agincourt; User:Bilou, Liftarn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle formations of the French and English at Agincourt; User:Bilou, Liftarn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

To further capitalize on the poor conditions of the soil, stakes were installed ahead of the archers to dissuade or impair the charge of any cavalrymen. As the bulk of his troops prepared for the frontal assault, Henry V also sent covert cells of archers into the bordering woodlands with hopes of surprising their foes during the later course of the battle.

On the other side of the arena, the French arranged themselves in three rows of several thousand each with Charles leading the first, the Duke of d’Alençon and Duke of Bar leading the second, and the Count of Falconberg and Count of Merle leading the third who rode on horseback. Between the first two dismounted rows rested the line of their archers. Charles also positioned mounted cavalrymen on the flanks of either edge of the rows. Though, with so many leaders in charge of different positions of its many moving parts, the French lines were too disorganized to control holistically – a key aspect of the ensuing fight that would contribute to its outcome.

A Tense Standoff Pierced by Arrows

Although both sides were prepared for war by 7 am, neither marched on the other for the next three to four hours. It was during this time that King Henry V and his men bent their knees in prayer, kissing the earth beneath them and placing a scrap of soil into their mouths so as to familiarize themselves with the taste of what may soon become their final resting place. As midday approached, it would be the English King to break the stand-off, proclaiming “Banners forward!”

Modern battle re-enactor with medieval English longbow and arrow; Stock Image

After dislodging their stakes, the English army pressed toward the French line. As the French began to regain the formations they had arrogantly disassembled to enjoy lunchtime, King Henry V signaled for his bowmen carefully hidden within the forest to unleash their deadly payload.

The sky blackened above the French as hellish volleys of arrows rained death upon their forward lines. Incensed by the taunting gibelike of the English archers slewing hunting cries as their arrows began claiming lives, the French were provoked into an advance.

A Punished Charge

What seemed to the French like a charge from both sides proved otherwise when Henry V gave the order for his men to reassert their stake defenses once within longbow’s reach. Although tasked with riding ahead to punish the lines of English archers and allow for the better momentum of their foot soldiers, the French cavalrymen were slowed immensely by the muddy gumbo beneath the heavy hooves of their horses. Soon enough, they too were subjected to the unrelenting severity of the English arrows.

Manuscript illumination of the Battle of Agincourt (early 15th Century); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Manuscript illumination of the Battle of Agincourt (early 15th Century); See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Volley after volley continued to cast down upon the French lines, finding perch in the bodies of many a poor soldier. The carnage proved too much for some of the French horses who, after bucking their riders, then galloped back towards the French line, causing more chaos among the ranks as they barrelled in blind fear through the lines of their masters. Before even reaching the lines of English men-at-arms, much of the French’s frontline troops had already begun their retreat.

By the time the French had reached a distance wherein their swords proved useful, both their numbers and resolve had already dwindled enough for the English to have garnered a fighting chance. It was only by the downright might of their body mass that some ground was taken from the English. But the ongoing barrage of arrows and the greater reach offered by their closer proximity to the volleys weakened their momentum further. To make matters worse, the incoming second wave from their rear saw to only crush and entrap the suffering forward ranks.

Battle of Agincourt from St. Alban’s Chronicle by Thomas Walsingham (c. 1422); Unknown – Ms 6 f.243 Battle of Agincourt, 1415, English with Flemish illuminations, from the ‘St. Alban’s Chronicle’ by Thomas Walsingham (vellum), English School, (15th century), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle of Agincourt from St. Alban’s Chronicle by Thomas Walsingham (c. 1422); Unknown – Ms 6 f.243 Battle of Agincourt, 1415, English with Flemish illuminations, from the ‘St. Alban’s Chronicle’ by Thomas Walsingham (vellum), English School, (15th century), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Seizing upon the opportunity presented to them, the English bowmen switched to melee weapons and bolstered the thin lines of their men-at-arms. Finding it easier to navigate through the mud with their significantly lighter armor, their addition to the sword clash issued a staggering blow to the tiring French formations. All the while, Henry V’s forest-bound bowmen continued to deliver volleys into the softened French lines. Charles d’Albret himself, along with a substantial portion of the French nobility, would meet his end on the battlefield.

The Desolation of the French Army

Within no more than two hours of combat, the French were in retreat toward the unengaged third wave who now vacillated on whether to join the fight, ultimately deciding against the notion. All that was left now was for the English to rout and subdue the remaining Frenchmen at the point of contact, as many as 2200 of whom were eventually taken as prisoners.

Battle of Agincourt from the Vigils of Charles VII (c. 1484); Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Battle of Agincourt from the Vigils of Charles VII (c. 1484); Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

During this round-up, a retinue small enough to slip past the English lines – led by the noblemen Robert de Bournonville and Isambart d’Agincourt – would ransack the invading army’s campsite, making off with the King’s bedding and one of his crowns.

Although they were easily expelled from the English camp, this would be a key factor in determining Henry V’s next move: having forebodings about an attack on his rear, the King would forgo the traditional rules of warfare by ordering the systematic execution of nearly all captured Frenchmen.

The wavering third line of French soldiers eventually turned tail as well after Henry V sent forth a message promising no quarter should they attempt to test the prowess and resolve of his men any further.

Aftermath

Remarkably, despite their immense numerical disadvantage and the ill state in which they were forced to do battle, the English army suffered no fewer than 600 casualties. For the French, however, roughly 5000 men met their deaths at the Battle of Agincourt. The victorious King Henry and his men then marched proudly to the town of Calais from whence they returned to England as heroes, his authority at home and its presence in France now firmly consolidated. However, this would not be the last battle between Britain and France.

The Battle of Agincourt was a decisive event in the history of medieval Europe, culminating in the defeat of the French army against England, whose leader, King Henry IV, was subsequently able to reconsolidate the island country’s control of French territory and abate the growing domestic tensions that would have otherwise toppled his rule. The battle is one of the most acclaimed to have occurred during the Hundred Years’ War. It showcased the superiority of good tactics over manpower, and the lethal effectiveness of the English longbow.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Won the Battle of Agincourt?

It was the English who won the Battle of Agincourt. Despite a numerical disadvantage of roughly two-to-one, King Henry V and his army successfully defeated over 12000 French soldiers.

When Was the Battle of Agincourt Fought?

The Battle of Agincourt occurred during the medieval period, spanning between 1337 AD – 1453 AD. On October 25th 1415, the English battled the French outside the town of Agincourt in France and emerged victorious.

When Was the Last Battle Between Britain and France?

The last time Britain and France would be locked in any key conflict would be between 1793 – 1815, during the Napoleonic Wars. This period ended in 1815 following the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.