Greek Goddess Persephone – Seasonal Queen of the Underworld

What is Persephone the goddess of, and what is Persephone’s Roman name? In the Roman era, Persephone was known as Proserpina, and to the Greeks, she was the Queen of the dead and the Underworld, but also the goddess of resurrection and Spring. This article will explore Persephone’s Greek mythology, including everything you want to know about Persephone’s personality and Persephone’s symbols. Join us below, as we find out more about Persephone’s story and the role that she played in Greek mythology!

The Greek Goddess Persephone’s Story

| Name | Persephone |

| Gender | Female |

| Symbols | Pomegranate, seeds of grain, torch, flowers, and deer |

| Personality | Reasonable, compassionate, and receptive |

| Domains | The Underworld and the Greek goddess of Spring |

| Parents | Zeus and Demeter or Zeus and Styx |

| Spouse and lovers | Hades, Adonis, Zeus |

| Children | Iacchus, Dionysus/Zagreus/Sabazius, Erinyes |

As well as being the Greek goddess of Spring and regeneration, the Greek goddess Persephone is also regarded as the Queen of the Dead and the Underworld. But, how did it come to be that a child of the goddess of agricultural fertility and almighty Zeus would end up in the Underworld in the first place? We will explore who the Greek goddess Persephone’s family is and her role in Greek mythology.

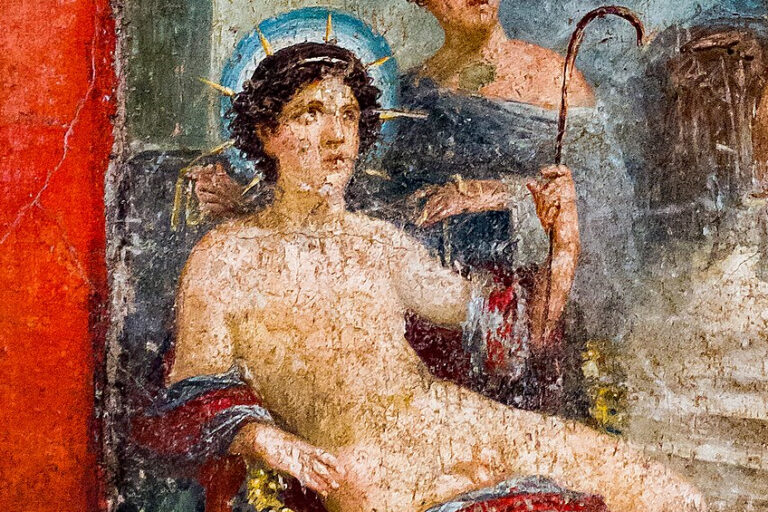

Tondo of a red-figure Kylix showing Persephone and Hades in the Underworld (c. 440-430 BCE); British Museum, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Tondo of a red-figure Kylix showing Persephone and Hades in the Underworld (c. 440-430 BCE); British Museum, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

The Family and Background of Persephone

Persephone is one of the rare characters in Greek mythology whose parentage was traditionally widely agreed upon. Her father was the king of the gods Zeus, and her mother was Demeter, goddess of fertility and agriculture, Demeter. These were some references to her as the daughter of Zeus and Styx, the river of the Underworld, but this was mainly a reflection of her role as the queen of the dead.

As a young maiden before her marriage, she is referred to as Kore, but as the Goddess of the dead she is always named Persephone.

In Rome, Persephone was identified with Proserpina, the goddess presiding over the germination of seeds, whose cult was associated with Dis Pater, the god of the dead who would later be assimilated with the Greek Hades under the name Pluto.

Roman-Germanic votive stone to the god Dis Pater and the goddess Proserpina; Arnaud Fafournoux, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman-Germanic votive stone to the god Dis Pater and the goddess Proserpina; Arnaud Fafournoux, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Once associated with Persephone, Proserpina’s parents became the Roman versions of Zeus and Demeter, namely Jupiter and Ceres.

Despite being a fertility goddess, as the spouse of the god of the Underworld, Persephone was not associated with motherhood. One exception was in the mystery cults where she was associated with the origin myths of Dionysus/Zagreus/Sabazius, and was either the mother or sister of a shadowy figure named Iacchus who served as the initiates’ guide in the Eleusinian Mysteries. In some myths she also produced the Erinyes, goddess who tormented those who spilled the blood of their relatives.

Persephone’s Story of Abduction to the Underworld

When Zeus and his brothers divided the world, Zeus received the sky, Poseidon the oceans, and Hades, the underworld. Zeus and Poseidon quickly took wives and multiple lovers, but Hades remained in the underworld content with managing the dead. However, one day he caught a glimpse of Zeus and Demeter’s daughter Persephone, and was instantly smitten.

Hades approached Zeus and asked to marry his daughter. Zeus agreed, but did not inform Demeter who he knew would object to losing her child to Underworld.

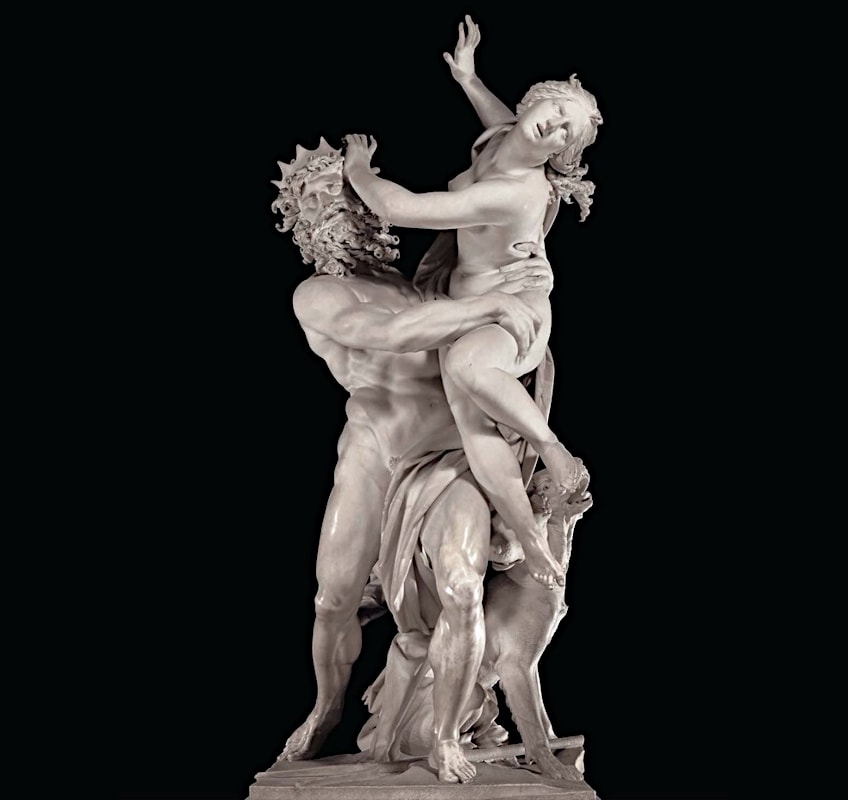

The Rape of Proserpina (Persephone) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1621-1622); Gian Lorenzo Bernini, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Rape of Proserpina (Persephone) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1621-1622); Gian Lorenzo Bernini, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Persephone was collecting flowers in a field with her companions when Hades appeared, bursting from a hole in the earth, to make her his wife. The Sicilians, who were presumably introduced to her worship by Megarian and Corinthian immigrants, thought that a well emerged on the location where Hades took Persephone down with into the underworld. The Cretans believed that the abduction took place on their own island, whereas the Eleusinians identified it as the Nysian plain in Boeotia and maintained that Persephone had fallen with Hades into the underworld at the point of entry to the western Oceanus.

When Demeter could not find her daughter, she looked all over the Earth with the torches of Hecate. In most tales, she either forbade the earth from yielding crops or neglected the soil and, in her grief, caused nothing to grow.

It was the sun, Helios, who eventually told Demeter where Persephone had been taken after witnessing it all occur from his position in the skies.

Ceres (Demeter) Begging for Jupiter’s (Zeus’) Thunderbolt after the Kidnapping of her Daughter Proserpine (Persephone) by Antoine-Francois Callet (1777); Antoine-François Callet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ceres (Demeter) Begging for Jupiter’s (Zeus’) Thunderbolt after the Kidnapping of her Daughter Proserpine (Persephone) by Antoine-Francois Callet (1777); Antoine-François Callet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Due to the subsequent failure of the crops, both mortals and gods began to ask Zeus to do something to stop the famine, and he told Hades that he had to return Persephone to Olympus. Hades agreed, however, Ascalaphus, custodian of Hades’ orchard told the gods that he had seen Persephone eat a pomegranate seed while she was in the realm of the dead, binding her to her new home and husband.

Eventually a compromise was reached where Persephone would stay in the Underworld for a third of the year. The rest of the time, she was allowed to stay with her mother.

Persephone finally returned from the underworld and was reunited with Demeter near Eleusis, according to the hymn. The Eleusinians constructed a temple beside Callichorus’ spring, and Demeter established her mysteries there. In some versions, Eubuleus the swineherd witnessed a girl in a chariot driven by an unseen rider being dragged off into the ground. Eubuleus was giving food to his pigs at the entrance to the underworld when she became engulfed by the ground. This part of the narrative provides an explanation for the association of pigs with ancient ceremonies in Eleusis and Thesmophoria.

Red-figure Bell-krater with a depiction of Persephone ascending from Hades guided by Hermes and Hecate while Demeter waits to greet her (c. 440 BCE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Red-figure Bell-krater with a depiction of Persephone ascending from Hades guided by Hermes and Hecate while Demeter waits to greet her (c. 440 BCE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Role of the Greek Goddess Persephone

When Demeter and her child reconnected, the Earth bloomed with flora and color, but when she returned to Hades for a few months each year, the land became empty and barren once more. This myth has traditionally been used to explain the seasons. Therefore, Persephone’s role in Greek mythology is related to this changing of the seasons. The ground starts to melt as Hermes brings her from the underworld and back to Demeter.

While Persephone and Demeter are united, the Earth enjoys spring and summer. During fall and winter, the earth feels Demeter’s sadness while Persephone is with Hades.

Demeter Mourning Persephone by Evelyn de Morgan (1906); Evelyn De Morgan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Demeter Mourning Persephone by Evelyn de Morgan (1906); Evelyn De Morgan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Persephone served as the queen, but also as a protector in the Underworld. Hades interacted often with many heroes who wandered into his realms, such as Odysseus, Hercules, and Orpheus, and was typically not very forgiving once he discovered them. The Greek goddess Persephone would intervene and save people from what would frequently be horrific ends, and in most cases, these Greek heroes ended up owing their lives to her.

Persephone’s Personality and Attributes

Persephone is typically characterized as beautiful, elegant, and bright. Her charms and charisma enchant others around her, even Hades, who fell in love with her when he saw her from the underworld. Persephone is portrayed as sympathetic and kind, especially towards the spirits of the deceased.

In certain stories from Greek mythology, Persephone exhibits sympathy and compassion for the souls trapped in the underworld, often providing them with solace and guidance.

Apulian red-figure volute-krater showing Persephone enthroned in the Underworld receiving a dead warrior (c. 340-320 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Apulian red-figure volute-krater showing Persephone enthroned in the Underworld receiving a dead warrior (c. 340-320 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Persephone is viewed as a strong and adaptable figure as she copes with the tragedy of her abduction and adjusts to her role as the Queen of the Underworld. Despite these horrible circumstances, she retains a sense of dignity and courage while traversing the worlds of both the living and the dead.

Persephone’s Symbols

The pomegranate is one of the most recognized of Persephone’s symbols. It reflects her sojourn in the underworld and her relationship with Hades. Various reasons have been proposed for why eating the pomegranate seed would have bound Persephone to Hades. This fruit was sacred to Hera and Aphrodite, goddesses of marriage and love. In addition, in ancient Rome, married women wore headdresses woven from pomegranate twigs, suggesting an association between this fruit and marriage.

Other explanations point to the notion that in order to escape from the Underworld, one could not partake of any part of it. As it was the keeper of Hades’ orchard who saw Persephone eat a pomegranate, it was clearly not something she brought with her from the land of the living.

Proserpine by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1874); Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Proserpine by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1874); Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As a goddess of regeneration, Persephone is also associated with flowers, especially spring blossoms. Her emergence from the underworld to the surface world caused plant regrowth and blossoming, representing the onset of spring.

Persephone often appears holding a torch, indicating that she serves as a source of guidance in the underworld.

The torch symbolizes her power to guide souls and bring light to the secrets of the afterlife. Persephone is also connected with grain because of her relationship with Demeter and the cycles of agriculture.

Physical Traits

Persephone is usually represented as a youthful and attractive goddess, reflecting what she represents as a symbol of vitality and the natural rhythms of life. Persephone is portrayed as having luscious flowing hair that cascades down her back. Her hair is occasionally decorated with flowers or a wreath to represent her love of springtime and nature. Persephone appears in royal regalia that represent her position as queen of the underworld.

Persephone’s expression in artworks is one of tranquility or delicate elegance, and artists often depict her with peaceful and placid facial features.

Red-figure volute-krater showing Orpheus playing for Persephone who sits on her throne and is flanked by Hecate and Hades (c. 350-325 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Red-figure volute-krater showing Orpheus playing for Persephone who sits on her throne and is flanked by Hecate and Hades (c. 350-325 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Persephone’s Domains of Influence

The Greek Persephone’s story is inextricably linked to the seasonal cycle. Her kidnapping and return from Hades represent the shifting of the seasons, especially the shift from winter to springtime. She is regarded as a patroness of agricultural abundance. Persephone’s journey from the underworld to the surface symbolizes the rebirth of agricultural life, indicating abundant harvests.

Persephone plays an important role in the realm of the deceased. She is connected to the soul’s journey, functioning as a protector in the afterlife.

The relationship between Persephone and the afterlife emphasizes her role in the passage from life to death and learning to exist in the underworld.

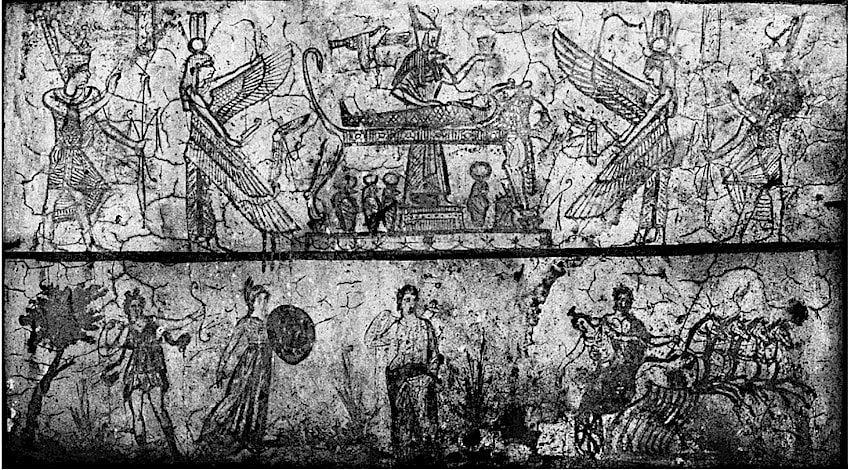

Fresco from The Persephone Tomb in Kom el-Shoqafa showing an Egyptian burial on the upper register with the abduction of Persephone on the lower right (2nd Century CE); Painter: 2nd century CEPhotographer: undetermined, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco from The Persephone Tomb in Kom el-Shoqafa showing an Egyptian burial on the upper register with the abduction of Persephone on the lower right (2nd Century CE); Painter: 2nd century CEPhotographer: undetermined, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Persephone is associated with Greek mystery religions, including the Eleusinian Mysteries. These mysterious religious ceremonies were based on Demeter and Persephone’s story and included initiations and ceremonies centered on the cycle of life. The abduction and return of the Greek goddess Persephone from the underworld were also significant in women’s rites. Persephone’s story represented the phases of girlhood to adulthood, symbolizing maiden, wife, and queen.

Persephone’s voyage functioned as a metaphor for a woman’s maturity and introduction into various stages of life.

Persephone in Greek Mythology

Persephone’s abduction is the most well-known of her myth stories, and even this tale has many variations. According to one version, Persephone was out playing with the nymph Hercyna, when she let a goose free.

The goose ventured into a deep cave and hid beneath a stone; when Persephone lifted the stone in search of the bird, water began to flow from the exact spot, and a river emerged that became known as Hercyna.

According to Boeotian tradition, this is where Hades snatched her. However, there are several other myths involving Persephone that are also worth exploring.

Grave stele of a young girl from Athens with a goose (c. 310 BCE); Glyptothek, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Grave stele of a young girl from Athens with a goose (c. 310 BCE); Glyptothek, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Persephone and Adonis

Adonis was a stunning human with whom the Greek goddess Persephone fell deeply in love. Aphrodite caused an unmarried couple to have a child and handed him to Persephone to foster when his parents abandoned him. Adonis grew up to be an unusually handsome young man, which is when Aphrodite wanted him back. Persephone refused to return him to her.

When the issue was brought before the god Zeus, he decided that Adonis would spend one-third of the year with either goddess and the other third to himself. Adonis preferred to spend his time with Aphrodite during the year.

Either Apollo disproved of Aphrodite’s obsession with this human, or Ares grew jealous, but one of them sent a boar to kill Adonis during a hunt. After this, he had no choice but to return to the Underworld. In another version of this story, Persephone met Adonis only after he was killed by a wild boar. Aphrodite traveled to the Underworld to retrieve him, but Persephone, in love with him, refused to let Adonis go until they agreed that he would travel between the land of the dead and the living each year.

Venus (Aphrodite) and Cupid (Eros) Lamenting the death of Adonis by Cornelis Holsteyn (1655); Cornelis Holsteyn, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Venus (Aphrodite) and Cupid (Eros) Lamenting the death of Adonis by Cornelis Holsteyn (1655); Cornelis Holsteyn, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The myth of Adonis echoes that of Aphrodite’s Mesopotamian counterparts Inanna and Ishtar whose son-lover Dumuzi or Tammuz would die and be resurrected on an annual basis, making Adonis the male version of Persephone.

Myths of Persephone’s Kindness and Wrath

After a plague struck Aonia, its inhabitants sought advice from the Oracle of Delphi, who informed them that sacrifice was required to placate the rulers of the underworld. Metioche and Menippe (Orion’s daughters) agreed to be sacrificed to the king and queen of the underworld in order for them to save their land. Hades and Persephone took pity on them as they were taken to the altar to be sacrificed and changed into comets instead.

Great Comet of 1861 by E. Weiss (published 1888); E. Weiß, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Great Comet of 1861 by E. Weiss (published 1888); E. Weiß, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Orpheus the Greek hero once journeyed into the underworld in search of his wife Eurydice, who died from a snakebite. His song was so wonderful that it enchanted Persephone as well as Hades. The Greek goddess Persephone was so taken with Orpheus’ lovely music that she convinced Hades to let him have his wife back. However, there was a condition, Orpheus could not look at Eurydice until they had reached the world of the living. Concerned that she may not be following him, Orpheus briefly glanced at her, and she immediately returned to Hades forever.

Orpheus in the Underworld by Jan Breughel the Elder (1594); Jan Brueghel the Elder, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Orpheus in the Underworld by Jan Breughel the Elder (1594); Jan Brueghel the Elder, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In another myth, Sisyphus, the cunning king of Corinth, avoided death by appealing to and fooling Persephone into letting him go; thus, he returned to the surface above. In yet another story, when the god of wine, Dionysus descended into the Underworld with Demeter to rescue his dead mother Semele and return her to the realm of the living, it is believed that he brought Persephone a myrtle plant as a gift in exchange for Semele.

Minthe was a nymph of the Cocytus River who was Hades’ mistress. Persephone was fast to catch on and stepped on the nymph, murdering her and transforming her into a mint plant out of jealousy.

In another version, Persephone ripped Minthe to shreds for sleeping with Hades, and it was he who transformed his former lover into the fragrant plant. In another story, Persephone’s mother, Demeter, murders Minthe for insulting her daughter. Hermes once followed Persephone with the intent of raping her, but the goddess screamed in fury, scaring him away and compelling him to back down.

The Worship of the Greek Goddess Persephone

Persephone was worshiped in the same mysteries as her mother the Greek goddess Demeter. Agrarian magic, dance, and rituals were all part of her cults. The priests utilized special dishes and sacred symbols, and the people sang rhymes in response. There is proof of sacred rules and other inscriptions in Eleusis. Their cult can be found throughout Attica, particularly in the great festivals of Eleusinian and Thesmophoria mysteries, as well as in a variety of minor cults.

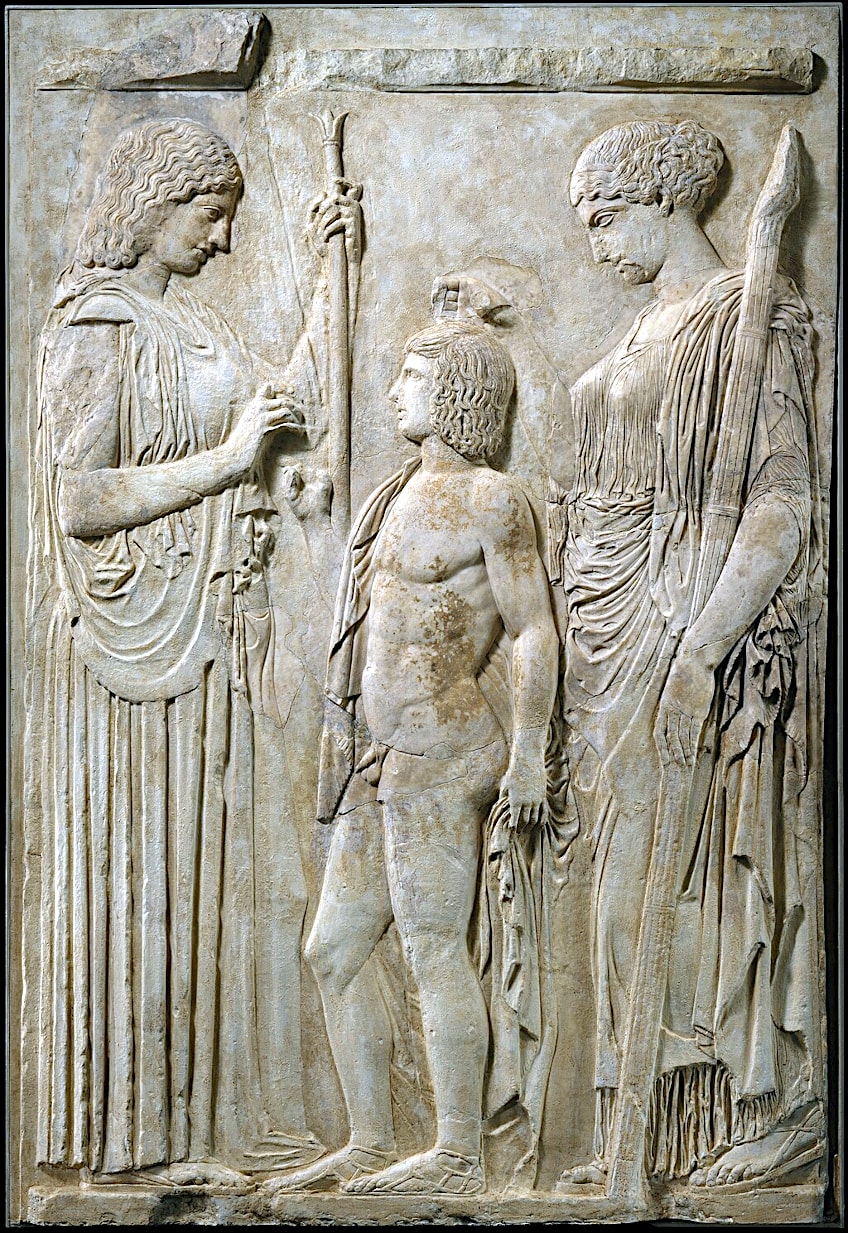

Ten fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief (c. 27 BCE – 14 CE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ten fragments of the Great Eleusinian Relief (c. 27 BCE – 14 CE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Most of the festivals associated with the cults of Persephone and Demeter were held during the fall sowing season and during the full moon.

Origins

According to Walter Burkert, Persephone is an old Chthonic goddess of agricultural cultures who accepted the souls of the dead into the earth and gained authority over the fertility of the land, over which she reigned. The oldest representation of a goddess Burkert thinks is Persephone emerging out of the ground can be found on a plate from Phaistos’ Old-Palace era.

A similar image, in which the goddess appears to descend from the sky, may be seen on a Minoan ring found in the tomb of Isopata.

Gold signet ring from the tomb of Isopata at Knossos (1500 BCE); Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Gold signet ring from the tomb of Isopata at Knossos (1500 BCE); Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Thesmophoria cults and Eleusinian mysteries of Demeter and the Greek goddess Persephone were founded on previous agrarian cults. These cults’ teachings were closely held mysteries, kept concealed since they were thought to offer adherents a better afterlife than the comparatively gloomy Hades. There is proof suggesting certain customs were derived from Mycenaean religious traditions. Carl Kerenyi argued that these religious traditions came from Minoan Crete.

The concept of immortality, which arises in syncretistic Near Eastern faiths, did not present in the Eleusinian mysteries at the outset.

The Mysteries

The Greek goddess Persephone was also connected with the Thesmophoria, a well-celebrated Greek celebration of secret women-only rites. These rites, which took place in the month of Pyanepsion, honored marriage and fertility and commemorated Persephone’s abduction and homecoming. However, the most famous rites associated with Persephone and Demeter were the Eleusinian Mysteries.

According to the myth Demeter found hospitality at Eleusis while searching for her daughter and rewarded its people by revealing her secret rites to them.

Only initiates could participate in the full rituals, and they were forbidden by Athenian law from revealing any details. Anyone who did, faced the death penalty. The entire ritual lasted nine days, and most likely involved some reenactment of the loss and return of Persephone. According to ancient accounts, the rite also included the revelation of the goddesses secret to new initiates, something sufficiently impactful to leave them in complete shock, yet it supposedly made them lose their fear of death.

Tondo of a red-figure Attic cup with a depiction of Triptolemus and Kore/Persephone (470-460 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tondo of a red-figure Attic cup with a depiction of Triptolemus and Kore/Persephone (470-460 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Inscriptions mention the Goddesses being escorted by the agricultural deity Triptolemos, and Persephone being joined by Eubuleus, who most likely guided the route back from the underworld.

Persephone in Locri

Some of the most revealing imagery of Persephone comes from objects used in her cult. In a rather unusual shift, Persephone and Hades were worshipped as the Divine Couple at Locri, one of the most sacred sites in Magna Grecia. Her kidnapping and relationship with Hades functioned as a symbol of the marital state in the imagery of votive plaques at Locri. Children there were devoted to Proserpina, and maidens who were about to get married would bring their peplos there to be blessed.

Votive painted terracotta tablets known as pinakes were often made in series and decorated in vibrant hues, inspired by images from Persephone’s story, and offered to the goddess around the 5th century BCE.

Many of these pinakes are currently on exhibit in Reggio Calabria’s National Museum of Magna Graecia.

Votive plaque showing Demeter and Persephone receiving initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries (c. 450 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Votive plaque showing Demeter and Persephone receiving initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries (c. 450 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Locrian pinake is both a record of religious activity and a piece of art. Most Greeks believed that the Greek goddess Persephone’s marriage to Hades precluded it from serving as an example of a successful human union. However, the Locrians, who had no fear of dying, saw Persephone’s destiny in a particularly favorable light. While Persephone’s return to the world above was essential to Panhellenic mythology, in southern Italy Persephone seems to have accepted her new position as the incredibly powerful queen of the underworld and may not even have returned to the world of the living.

Votive Tablet from the shrine at Locri showing Hades abducting Persephone (460-450 BCE); English: Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Votive Tablet from the shrine at Locri showing Hades abducting Persephone (460-450 BCE); English: Following Hadrian, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Despite the fact that she is married to Hades, who is not mentioned in the Pelinna tablets that have been found nearby, Persephone seems to possess absolute control over the underworld in Locri. The abduction of Persephone is frequently depicted in Locri, while other depictions place her atop a throne next to her beardless, young husband.

This suggests that in Locri, the abduction of Persephone served as a metaphor for young women’s transition from childhood to marriage—a change that is terrifying but also gives the bride a position and status in society. Thus, those depictions convey both the fear of marriage and the victory of the young woman when she becomes a wife. A Demeter sanctuary has been discovered in a separate area of Locri, refuting the idea that she was totally excluded and that Persephone’s worship at Locri was fully autonomous from Demeter’s.

Psychological Interpretations

The archetypal and symbolic elements of the Greek goddess Persephone’s narrative are explored in psychological interpretations of her story, along with the story’s applicability to the human psyche and the processes of personal development. Many people see Persephone’s voyage into the underworld as a symbolic excursion into the subconscious or dark sides of the psyche.

The depths of the human mind are symbolized by the underworld, which is home to suppressed emotions, unfulfilled desires, and unresolved events.

It is possible to see Persephone’s tale as a probe and fusion of these internal parts of the self. The tale of Persephone is consistent with Carl Jung’s psychological theory of individuation. The process of self-realization and integrating one’s entire identity, including their shadow, is referred to as individuation. This transforming path towards completeness and self-discovery might be understood as symbolically represented by Persephone’s kidnapping and later return. The merging of the psyche’s light and dark elements is emphasized in the Greek goddess Persephone’s story.

The Rape of Persephone by Rupert Bunny (c. 1913); Rupert Bunny, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Rape of Persephone by Rupert Bunny (c. 1913); Rupert Bunny, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Her experience in the underworld represents coming face to face with one’s shadow self, the more sinister and usually suppressed facets of their psyche. Persephone becomes a more whole and genuine version of herself by accepting and integrating her dark sides. The tale of Persephone also includes notions of rebirth and fortitude. Her ascent from the dead represents a psychological process of regeneration and rebirth. This part of her tale emphasizes how people may change and evolve even in the face of difficult or terrible circumstances.

The Greek goddess Persephone had a number of significant roles in the mythology of the ancient Greek world, but she is most recognized for being the Greek Goddess of regeneration and the Underworld. Persephone, like her mother Demeter, was a goddess of agriculture who oversaw plants and grains. She was an Olympian deity who served in her own right, but she also shared control of the Underworld with Hades. While she was the Queen of the Underworld, she was also known to be a compassionate figure who often helped those who had found themselves there.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Persephone the Goddess Of?

According to Persephone’s Greek mythology, she was regarded as the goddess of Death and the Underworld. She spent part of every year with her husband Hades and the remainder of her time with her mother Demeter. Her journey from one realm to the other has been associated with the changing of the seasons, abundant harvests, and spring flowers.

What Is Persephone’s Roman Name?

As with the majority of the gods and goddesses of ancient Greece, Persephone was eventually integrated into the Roman pantheon of gods. In the Roman era, she was known as Proserpina. Rome typically recognized Proserpina as the native Italic goddess Libera in 205 BCE. Liber and Proserpina were both strongly linked to the Roman goddess of grain, Ceres. Proserpina was also compared by Gaius Julius Hyginus, the Roman poet, to Ariadne, the Cretan goddess who was the spouse of Liber’s Greek counterpart, Dionysus.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.