Greek God Dionysos – Liberating God of Wine and Ecstasy

The Greek god Dionysos is primarily known for his role as the god of wine-making in the mythology of ancient Greece. The Greek god of wine is associated with fruit, orchards, fertility, festivities, theater, religious ecstasy, and ritual madness. Dionysus’ Roman name is Bacchus, and Dionysus’ symbols include the thyrsus staff, ivy, theatrical masks, and grapevines.

The Mythology of the Greek God Dionysos

| Name | Dionysos/Dionysus or Bacchus |

| Gender | Male |

| Parents | Zeus and Semele |

| Personality | Ecstasy, merriment, and joy |

| Siblings | The Olympians |

| Spouse | Ariadne |

| Domain | Winemaking and festivities |

| Symbols | Ivy, grapevine, theater masks, and thyrsus staff |

As the Greek god of wine, Dionysus was renowned for whipping up a frenzy of dance, merriment, and even ecstasy in those who partook in his mysteries and festivities. The cult of the Greek god Dionysos regarded wine with religious reverence and it was believed to be the physical incarnation of Dionysus on Earth. In the ancient world, wine was praised for its ability to take away sorrow, bring bliss, and instigate divine insanity.

In everyday settings, the Ancient Greeks drank their wine diluted with water, regarding those who did not do the same as complete savages.

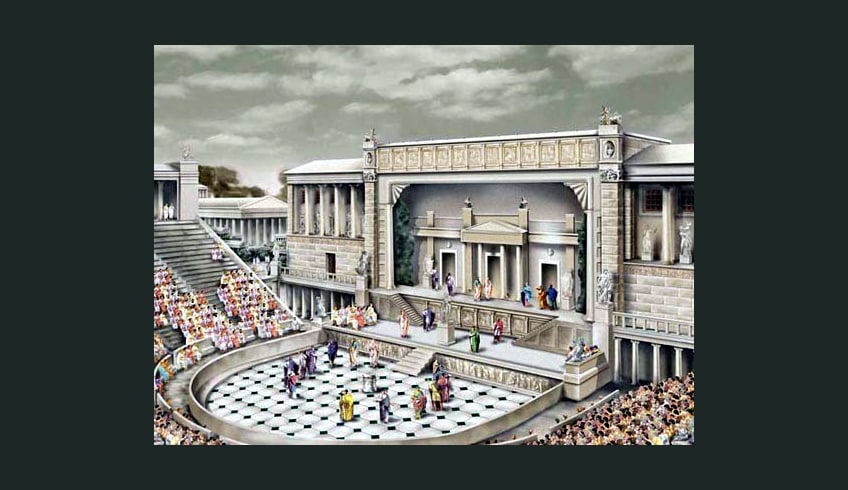

At the festivals held in honor of the Greek god Dionysos, people reenacted scenes from his myths, which was the origin of theatrical performance in Western culture. Dionysus’ was known to the Romans as Bacchus and he is associated with fertility, wine, and guarding tradition.

Reconstruction of an ancient Greek theater; А. Әбілхан, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction of an ancient Greek theater; А. Әбілхан, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Background of the Greek God Dionysos

Many 19th-century academics thought of Dionysus as a foreign god who was possibly only accepted as a part of the pantheon of gods in Greece at a fairly late time period. This is based on the common theme that permeates much of his mythology – a deity who devotes much of his earthly time to other regions and finds it hard to gain acceptance once returning to Greece.

Yet, research conducted in more recent years has revealed that he was actually one of the first gods worshiped in the culture of mainland Greece, with the earliest documented records emerging from Mycenaean Greece.

Linear B tablets were discovered at Mycenean period archaeological sites inscribed with the names di-wo-nu-so and di-wo-ni-so-jo, one of which describes offerings of honey to Zeus and Dionysos. Other tablets refer to the worship of Eleutherios (the liberator), who was regarded as the son of Zeus, to whom oxen were offered in sacrifice. In later myth and cult, Eleutherios was an epithet of the Greek god Dionysos, although it was also applied to Eros and Zeus himself.

Linear B inscription relating to sacrifices consisting of honey dedicated to the gods Zeus and Dionysus, suggesting the existence of a sanctuary of Zeus in the Chania region since 1300 BCE; Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Linear B inscription relating to sacrifices consisting of honey dedicated to the gods Zeus and Dionysus, suggesting the existence of a sanctuary of Zeus in the Chania region since 1300 BCE; Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Some historians believe that the predominant cult of Dionysus, as well as his most significant myths, were already in existence as early as the 13th century BCE. Iconography discovered on pottery from the 7th century suggests that Dionysus was venerated as more than just the Greek god of wine. He was also connected with death, weddings, sexuality, and sacrifice, and he already had an entourage of dancers and satyrs.

The transformation of the god’s worshippers into hybrid animals, often represented by both wild and tame satyrs, was a popular theme in these early portrayals, signifying the liberation from the inhibitions necessary for living within human society.

The Greek God Dionysus’ Birth

In Dionysos’ so-called “second birth” narrative, Hera had discovered that Zeus had made a human girl named Semele his lover. Disguised as her nurse, Hera convinced Semele to establish proof that her lover was indeed a god by asking Zeus to appear before her in his full divine splendor. The deeply smitten Zeus had previously promised to grant any wish the girl expressed, and was bound to honor her request.

Without the protective shield of his mortal disguise, the god’s divine presence incinerated Semele.

Zeus then noticed an infant inside her burning body. Since Semele had not yet carried her child to term, Zeus took the fetus and inserted it into his thigh, from where Dionysos was eventually born, hence his description as having been born twice. Dionysos was therefore unique in that he had been born from the body of a human mother and the body of a divine father.

The Death of Semele by Peter Paul Rubens (before 1640); Peter Paul Rubens, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Death of Semele by Peter Paul Rubens (before 1640); Peter Paul Rubens, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In another version of Dionysos’ origins, Zeus made love to Persephone in the shape of a snake, thus conceiving Dionysus. Zeus intended for Dionysus to be his heir as world king, but an envious Hera encouraged the Titans to murder the child. It is believed that when the Titans found him, they mercilessly mocked him and replaced his legitimate staff with a thyrsus staff (fennel stalk).

The Greek historian Diodorus recounts legends in which an older, Egyptian or Indian Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Persephone.

This Dionysus is reputed to have invented wine and shown mankind how to plow the land with oxen instead of by hand. His devotees were believed to have worshiped him by portraying him with horns. Dionysus also proved to be very popular upon his introduction to Rome, even though Roman authorities regarded his popularity amongst women and slaves with deep suspicion. The Roman Empire was a multi-cultural melting-pot of syncretic religions and mystery cults. The ecstatic rituals and ancient Orphic myths associated with Dionysos made this god fertile ground for acquiring new cultic associations. Mystery cults such as Orphism laid particular emphasis on Dionysos as a god of resurrection and liberating force. The Imperial era Greek poet Nonnus even described Zeus creating a new Dionysos, a bull-shaped version of an ancient Dionysos who was the Egyptian deity Osiris, another god known for his death and resurrection.

The Thracian Golden Orphism Book (500-600 BCE) is considered the oldest surviving codex related to Orphism; Ivorrusev, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Thracian Golden Orphism Book (500-600 BCE) is considered the oldest surviving codex related to Orphism; Ivorrusev, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Personality and Attributes of Dionysus

The Greek god Dionysus’s personality was said to be multifaceted, reflecting the various roles he played within his domains. Typically, he was portrayed as an exuberant and joyful deity who embodied the pursuit of pleasure and the celebration of life. During ecstatic rituals performed in the name of Dionysus, his worshipers would celebrate his presence through dance, song, and general merriment.

His wine had the ability to release people from their inhibitions and experience a sense of freedom, providing them with relief from their rule-bound lives. His personality was said to have a dualistic nature, and he symbolized the juxtaposition of opposites.

Red-figure skyphos with a depiction of a dancing maenad (c. 330-320 BCE); British Museum, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Red-figure skyphos with a depiction of a dancing maenad (c. 330-320 BCE); British Museum, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

This was because he was seen as both a god of the culture and the civilized world in addition to being a god of untamed nature. Therefore, he was equally associated with both divine inspiration and madness, order and chaos, the spiritual and the profane. While being associated with madness, he was also regarded as a compassionate god who offered solace to his worshipers in times of distress.

As the god-born son of a mortal woman, he was regarded as a bridge between the Earthly realm and the realm of the gods, enabling him to sympathize with the experiences of humans.

Dionysus’ Symbols

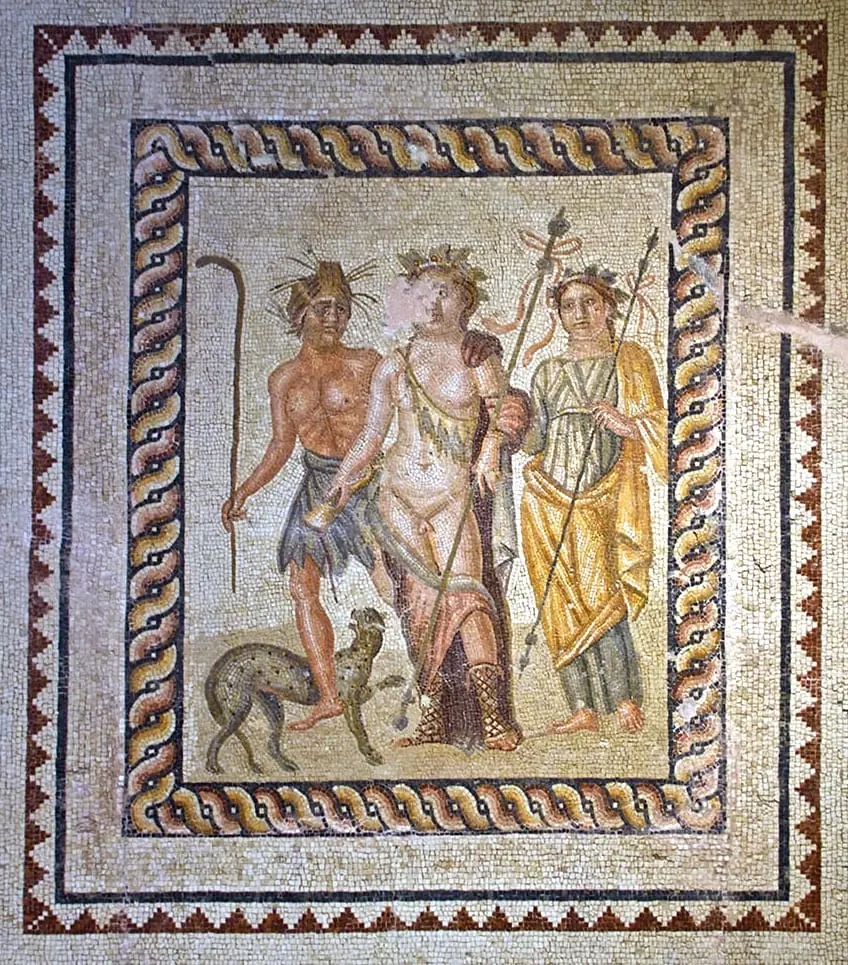

The earliest depictions of Dionysus portray him as an older, robed male with a beard. He is usually seen holding his fennel staff, known as a thyrsus, which is traditionally topped with a pine cone.

Subsequent depictions portray him without a beard and considerably younger, often described as womanly or androgynous.

In its most developed form, his cult iconography reflects a deity who has just returned from someplace beyond the civilized and known world. He is sometimes portrayed as being drawn in a chariot by tigers, lions, or other exotic animals. He was also associated with the bull and was considered to be a god of resurrection.

Roman mosaic showing Dionysos with his attributes including a thyrsus, panther, satyr, and maenad (2nd Century CE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman mosaic showing Dionysos with his attributes including a thyrsus, panther, satyr, and maenad (2nd Century CE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Often, he was portrayed with bull horns, a reference to an archaic legend in which he is slaughtered as a calf and then eaten by the Titans. Other symbols of the Greek god Dionysos included the phallus and the snake. He is also associated with fig trees, and linked with the transition from Summer to Autumn. Marked by the rising of Sirius, the dog star, the weather in the Mediterranean grows extremely hot in the summer, a sign that a time of harvests and abundance is on the horizon. When Orion would eventually take its place in the center of the sky in late Summer, the ancient Greeks knew it was time to harvest the grapes. It was not just the grapevines that he was associated with, but the cultivation of the land too.

Dionysos was regarded as a deity that promoted and assisted the growth of crops and ensured that there was abundance in nature. To symbolize a bountiful harvest, he was often depicted with a cluster of grapes.

The Domains of the Greek God Dionysus

As an important character in Greek mythology, Dionysos was typically associated with many different aspects of Greek culture and daily life. Dionysus was particularly connected with wine and grapevine cultivation. He has been linked to the development of wine production and taught humanity viticulture techniques. As a result, Dionysos was closely associated with the creation, use, and pleasures of wine, which played an important social and cultural role in ancient Greece.

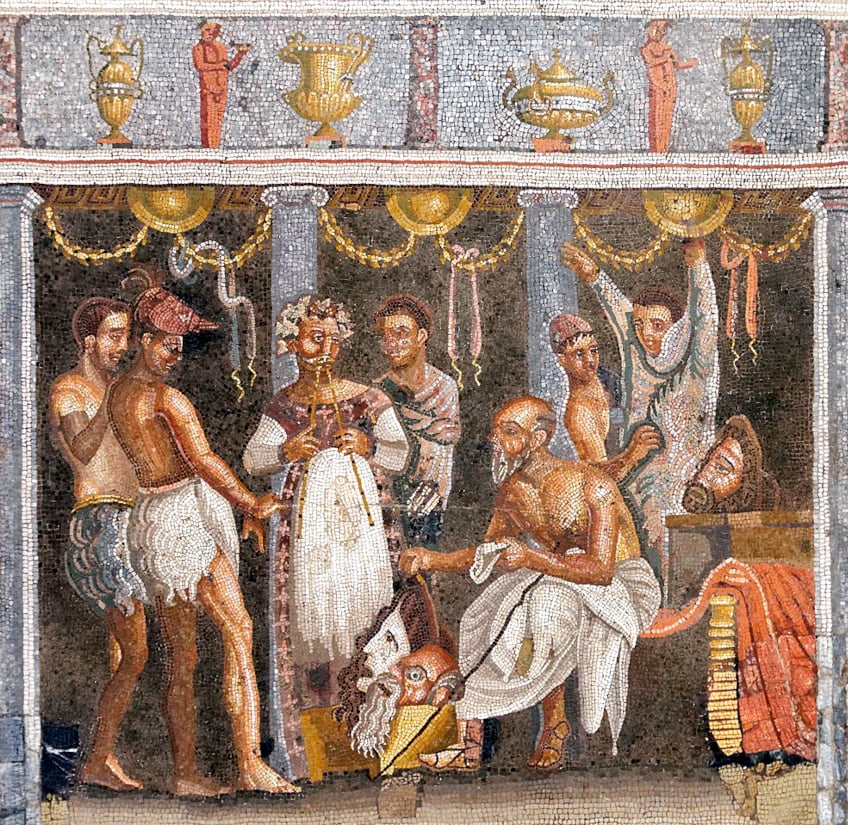

Dionysos was the focal point of several celebrations in his honor. The Dionysia and the Bacchanalia were the most well-known of these celebrations.

Theatrical performances, music, dance, and ecstatic rites were among the events that took place at these festivities. They provided opportunities for social interaction, creative expression, and religious devotion.

Roman mosaic showing Choregos and actors from Pompeii (1st Centuries BCE and CE); Naples National Archaeological Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman mosaic showing Choregos and actors from Pompeii (1st Centuries BCE and CE); Naples National Archaeological Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dionysus was revered as the patron deity of drama and theater. His festivals were inextricably related to the emergence as well as the performance of ancient Greek plays. Athens’ Dionysia festival featured dramatic competitions in which authors and actors exhibited their skills. Dionysus was a god of creativity, and his mere presence was thought to inspire writers and actors to greatness.

Dionysus was also linked with religious experiences of ecstasy. His rites and practices were designed to create altered states of consciousness and religious transcendence.

The participants indulged in wild dancing, singing, and intoxication in order to seek oneness with the heavenly and to experience states of pure bliss and release. Farmers sought his favor in order to assure abundant harvests and productive agricultural activities, as his dominion included agricultural land and the vegetation that grew on it.

The Myths of the Greek God of Wine

Now that we have a better understanding of Dionysus’ background and personality, we can take a look at the various myths that involve the Greek god Dionysos. They are provided in sequential order, enabling us to get a sense of his overall life story. Let’s begin with the mythology regarding his infancy.

The Infancy of Dionysos

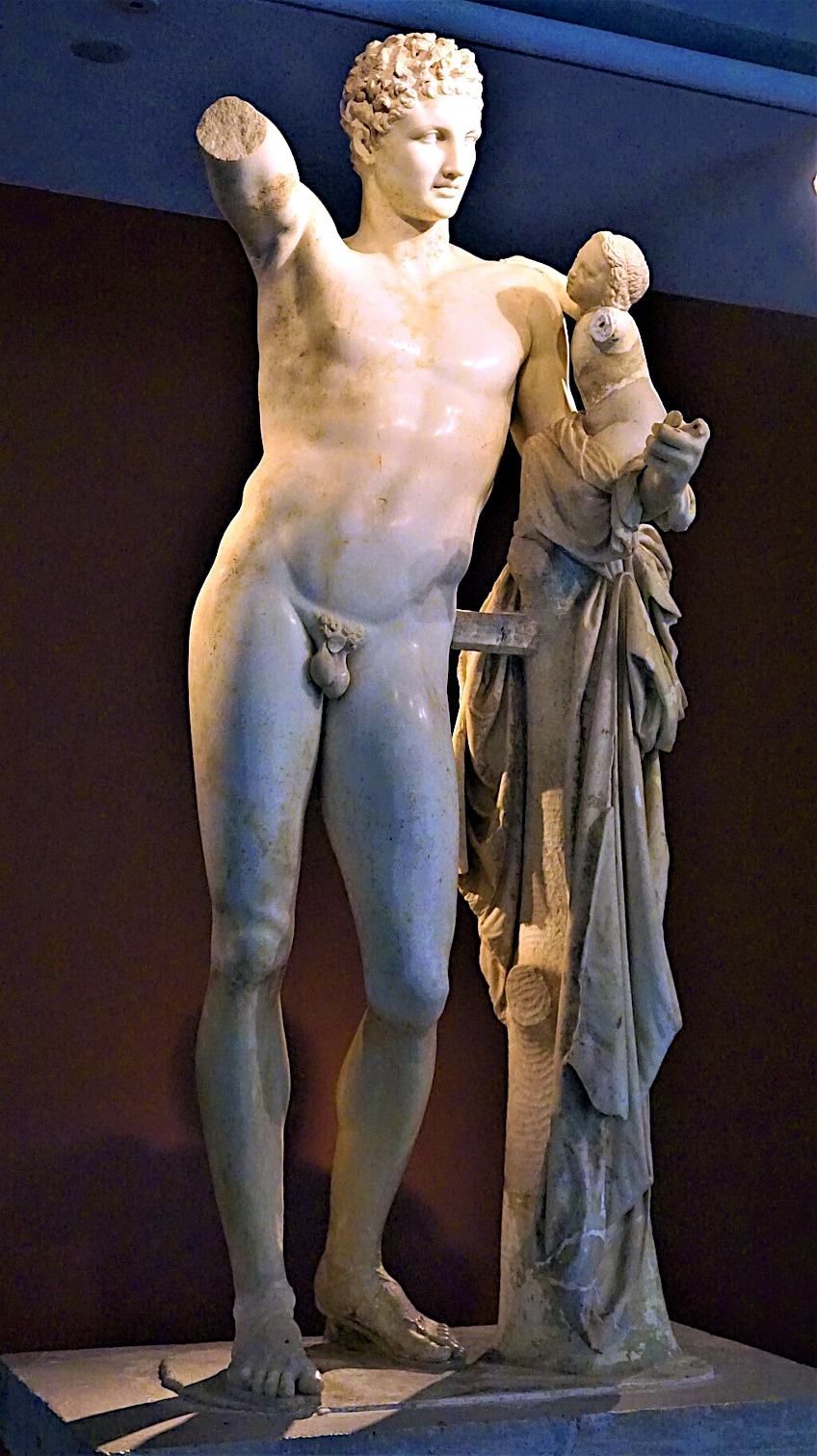

Zeus entrusted the care of the baby Dionysos to Hermes, according to the accounts of Nonnus. Hermes delivered Dionysos to the Lamos daughters, who were river nymphs. Hera, though, drove them insane, causing them to try and attack Dionysos, who was luckily saved by Hermes. Hermes then delivered the newborn to Ino for nursing by her servant Mystis, who instructed him on the ancient mystery and rites.

Statue of Hermes holding the infant Dionysus ascribed to Praxiteles (c. 4th Century BCE); Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of Hermes holding the infant Dionysus ascribed to Praxiteles (c. 4th Century BCE); Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to Apollodorus, Hermes urged Ino to disguise Dionysos as a girl to protect him from the wrath of Hera. Hera, however, recognized him and swore that she would demolish the home with a deluge; yet, Hermes saved Dionysos once more, this time carrying him to the Lydian highlands. Hermes assumed the shape of Phanes, one of the most ancient of the divinities, and Hera bowed and allowed him to pass. Hermes gave the newborn to the goddess Rhea, who raised him until he was an adolescent.

Dionysos’ Travels in Wine Invention

When Dionysos grew up, he was the first to learn about the culture of the vine and the method of obtaining its rich juice; nevertheless, Hera afflicted him with madness and carried him astray over different regions of the world. The goddess Rhea healed him and showed him her sacred ceremonies in Phrygia, and he went off on a journey around Asia educating the locals on how to cultivate the grape. His voyage to India, which is reported to have lasted many years, is the most renowned aspect of his journey.

According to one legend, when Alexander the Great arrived at Nysa, the inhabitants said that Dionysos established the city in the distant past and that it was devoted to him.

Dionysos’ Return to Greece

Dionysos was regarded as the creator of the triumphal parade after returning happily to Greece after his adventures in Asia. He attempted to establish his religion throughout Greece but was met with opposition from authorities who felt it would cause unrest and insane behavior. In one story, Dionysos returned to Thebes, his birthplace, which was ruled by Pentheus, his cousin. Pentheus, together with his mother Agave and aunts Autonoe and Ino, disputed Dionysos’ heavenly origins.

Despite Tiresias the blind prophet’s warnings, the Theban royal family rejected the cult of Dionysos and blamed him for driving the women of Thebes insane.

Dionysos instigated in Pentheus an overwhelming desire to observe the Maenads’ ecstatic ceremonies in the forests of Mount Cithaeron. Pentheus then hid himself in a tree in order to observe the sexual orgy. The Maenads saw him and, entranced by Dionysus, mistook the king for a mountain lion. The women, who included his mother, attacked him and tore him limb from limb. Agave then mounted his head on a pole and presented it to Cadmus. Dionysos then returned in his divine form, exiled Agave and her sisters, and turned his mother Semele’s parents Cadmus and Harmonia into snakes.

Attic red-figure lekanis with a depiction of Pentheus being torn apart by Agave and Ino (5th Century BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure lekanis with a depiction of Pentheus being torn apart by Agave and Ino (5th Century BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Imprisonment of the Maenads

When King Lycurgus of Thrace discovered that Dionysos and his retinue had entered his domain, he detained Dionysos’ female followers, the maenads. Dionysos escaped and sought sanctuary with Thetis, sending a drought that prompted the populace to rebel. The deity then drove King Lycurgus mad by having him slash his own child with an ax with the assumption that he was a piece of ivy, a plant sacred to the Greek god Dionysos. The region would remain dry and desolate for as long as Lycurgus lived, according to an oracle, and the population had him killed.

Dionysus lifted the curse after being placated by the king’s death.

In a different version of this myth, Lycurgus tried to kill Ambrosia, a Dionysian who had been turned into a vine that wrapped around the monarch and slowly choked him.

The Myth of the Attempted Kidnapping by Sailors

According to this myth, some sailors encountered Dionysus on the seashore and mistook him for a prince. They tried to abduct him and sail away with him so they could exchange him for a ransom or to force him into slavery. However, No rope they tried to use could tether him. The deity transformed into a ferocious lion, unleashing a bear on board, slaughtering everyone. Those that leaped from the ship were transformed into dolphins. The sole survivor was Acoetes, the helmsman, who recognized the deity and had attempted to stop his crew from the beginning.

Black-figure Etruscan Hydria with depictions of the Tyrrhenian pirates changing into dolphins (510-500 BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Black-figure Etruscan Hydria with depictions of the Tyrrhenian pirates changing into dolphins (510-500 BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Greek god Dionysus, in a similar myth, chartered a Tyrrhenian pirate ship to take him to Naxos from Icaria. When he got onboard, they traveled to Asia rather than Naxos, with the intention of selling him as a slave. This time, the god transformed the oars and mast into serpents and filled the ship with the sound of flutes, causing the sailors to go insane and, plunging into the water, to be transformed into dolphins.

Dionysos’ Descent into the Underworld

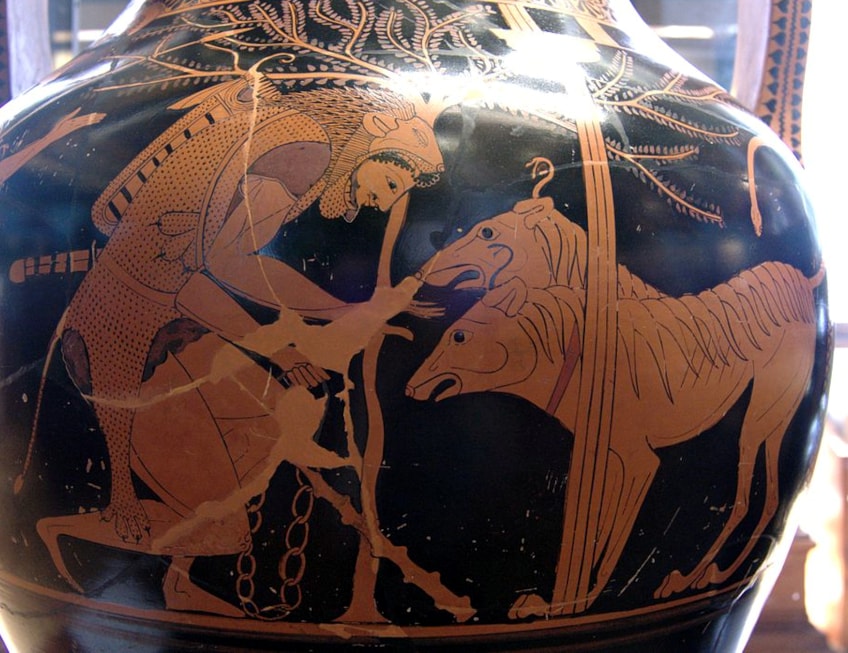

Pausanias mentions two different legends about Dionysus’ journey to the underworld. Both stories describe how Dionysos entered the realm of the dead to save his mother Semele and restore her to her proper position on Mount Olympus. To accomplish this, he had to deal with Cerberus, the hellhound, which Heracles restrained for him.

Attic red-figure amphora with a depiction of Herakles and Cerberus (530-520 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure amphora with a depiction of Herakles and Cerberus (530-520 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dionysus resurfaced with Semele from the bottomless waters of a lagoon on the shore of the Argolid near the prehistoric settlement of Lerna after recovering her. This mythical event was honored with an annual nocturnal festival, the specifics of which the local religion kept hidden. Dionysus’ emergence from the lagoon’s waters may represent a type of resurrection for both Semele and the Greek god of wine as they reappeared from the underworld.

According to one legend, Dionysus was accompanied on his voyage by Prosymnus, who asked to be Dionysus’ lover as his reimbursement. Prosymnus died before Dionysus could fulfill his promise, so Dionysus constructed a phallus from a fig branch and pierced himself with it at Prosymnus’ tomb.

This account remains in its entirety only in Christian sources, whose purpose seems to have been for clarifying the origin of hidden artifacts used by the Dionysian Mysteries. In a later version, he changed his mother’s name to Thyone and accompanied her to heaven, where she was elevated to the status of goddess. Before claiming his position among the Olympic gods, Dionysus had to first prove his godhood to humans, then validate his seat on Olympus by demonstrating his genealogy and raising his mother to divine status, according to this version of the narrative.

The Golden Touch of Midas

Silenus, Dionysos’s former foster father, had gone missing. The elderly man had walked away inebriated and was discovered by several peasants, who delivered him to King Midas. The king welcomed him with open arms and fed him for 10 days and nights as Silenus delighted him with stories and music. Midas returned Silenus to Dionysos on the 11th day. Dionysos presented the king with his choice of reward for the return of his foster father. Midas requested that everything he touched turn to gold.

Dionysos agreed, but warned the king that he would live to regret not making a better decision.

Midas was overjoyed with his newfound power, which he eagerly put to the test. He grabbed and transformed an oak twig and a rock into gold, but his delight was short-lived when he saw that his meat, bread, and drink had all turned to gold. When his daughter hugged him later that day, she also turned to gold. The terrified monarch tried all he could to get rid of the Midas Touch, and he begged Dionysos to spare him from starving. The deity agreed, sending Midas to bathe in the Pactolus River. The power poured into them as he did so, and the river sands became gold: this tale accounted for the Pactolus’ golden sand.

Midas and Bacchus by Nicolas Poussin (between 1629 and 1630); Nicolas Poussin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Midas and Bacchus by Nicolas Poussin (between 1629 and 1630); Nicolas Poussin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Lovers of Dionysos

Dionysos met and wedded Ariadne after Theseus abandoned her asleep on Naxos. She then gave birth to a son named Oenopion, but she either took her own life or was slain by Perseus. Dionysos had her crown placed in the skies, which became the constellation Corona in some versions; in others, he journeyed into the underworld to bring her back to the gods on Mount Olympus. According to another version, Dionysus commanded Theseus to leave Ariadne on the island of Naxos because he wanted to marry her.

Restored Roman fresco depiction Dionysos and Ariadne (1-79 CE); Getty Villa, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Restored Roman fresco depiction Dionysos and Ariadne (1-79 CE); Getty Villa, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Psalacantha, a nymph, promised to assist Dionysos in courting Ariadne in return for sexual favors; however, Dionysos refused, and Psalacantha warned Ariadne not to go with him. Dionysos transformed her into the plant of the same name as a result of this. In another myth, Dionysus was in love with Nicaea, a nymph, who was bound by Eros in some tales. Nicaea, on the other hand, was a vowed virgin who spurned his attempts to pursue her. So, while she was away one day, he changed the spring water she used for drinking to wine. Nicaea eventually passed out from intoxication, and Dionysus raped her.

When she awoke and realized what had occurred, she set out to find him and punish him but failed to find him.

In another myth, Eros was responsible for making Dionysus fall in love with Artemis’ virgin attendant, Aura, as an elaborate scheme to punish Aura for insulting Artemis. Dionysus employed the same trick as Nicaea, subsequently tying her up and raping her. Aura attempted suicide but was unsuccessful.

The Depictions in Art and Literature of Dionysus

The deity, and more often his entourage, were often represented in Ancient Greek painted pottery, much of which was designed to carry wine. Except for a few maenad reliefs, Dionysian subjects were uncommon in monumental sculpture until the Hellenistic era, when they rose in popularity. The deity himself appears in these in a variety of ways, ranging from Neo Attic types like Dionysus Sardanapalus to androgynous young males, usually naked.

The Barberini Faun is a well-known Hellenistic sculpture with Dionysian motifs that have survived in Roman replicas.

By the time of the Hellenistic era, the Dionysian world was portrayed as a hedonistic but protected pasture in which various semi-divine creatures of the countryside, like nymphs, centaurs, and the gods Hermaphrodite and Pan, were co-opted.

Black-figure krater with a depiction of Dionysos holding a wine cup accompanied by a satyr and maenads (c. 520 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Black-figure krater with a depiction of Dionysos holding a wine cup accompanied by a satyr and maenads (c. 520 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By this time, the word “nymph” merely referred to an idealized female of the Dionysian outdoors. For the first time, Hellenistic sculpture featured big genre subjects of peasants and children, many of whom wore Dionysian attributes including ivy wreaths, which were regarded as belonging to his realm. They share the characteristics of nymphs and satyrs in that they are outside beings with no distinct personal identity. The Derveni Krater, a one-of-a-kind 4th-century BCE metal vessel of exceptional beauty, portrays Dionysus and his entourage.

Apart from being a deity of pleasure, Dionysus intrigued Hellenistic rulers for a variety of reasons: he was a mortal who ended up being divine, he arrived from and ruled the East, he represented a lifestyle of majesty with his mortal followers, and he was often considered an ancestor.

He continued to make an impact on the wealthy of Imperial Rome, who adorned their gardens with Dionysian art and were regularly interred in sarcophagi carved with dense representations of Dionysus and his companions by the 2nd century CE. The British Museum’s Lycurgus Cup from the 4th century CE is a stunning cup that changes color when light passes through the glass; it depicts the imprisoned King Lycurgus suffering torture by the deity and tormented by a satyr; it could possibly have been used to celebrate Dionysian mysteries.

Roman mosaic floor with depiction of Dionysos with fruit and Ivy headdress (150-300 CE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman mosaic floor with depiction of Dionysos with fruit and Ivy headdress (150-300 CE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Early Modern Era Art

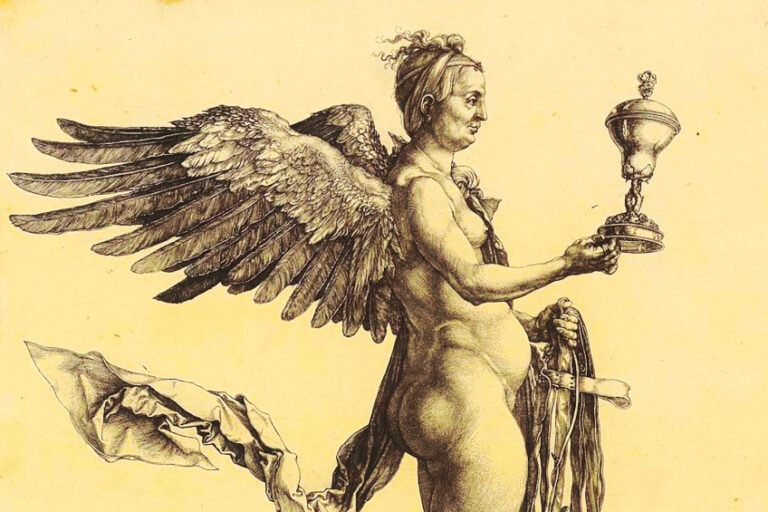

Dionysian topics in art were revived in the Italian Renaissance and quickly became nearly as prevalent as in antiquity, although his strong connection with feminine mysticism and authority almost vanished, as did the belief that the god’s creative and destructive energies were inextricably intertwined. “Madness has turned into merriment” in Michelangelo’s sculpture, Bacchus (1497). The statue attempts to convey both drunken incapacity and raised consciousness, but this was possibly lost on subsequent audiences, and the two parts were usually split thereafter, with an obviously drunk Silenus corresponding to the former and a youthful Dionysus frequently depicted with wings, as he carried the mind to higher destinations.

Bacchus by Caravaggio (1595); Caravaggio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bacchus by Caravaggio (1595); Caravaggio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Starting in the 15th century, depictions of Dionysus and Ceres taking care of a figure of love – usually, Venus or Cupid- were popular in art. The notion arose from a quote by the Roman comedian Terence, which became a common saying in the Early Modern era: “Venus freezes without Ceres and Bacchus”. Its most basic idea is that love requires food and wine to survive. From 1550 to 1630, artwork based on this statement was popular, particularly in Northern Mannerism in the Low Countries and Prague.

Dionysus became the deity of autumn as a result of his involvement with the grape harvest, and he and his companions often appeared in seasonal contexts.

Depictions in Literature

Dionysus has inspired painters, philosophers, and authors well into the contemporary era. Friedrich Nietzsche suggested in The Birth of Tragedy (1872) that the emergence of Greek tragedy was influenced by a conflict between Dionysian and Apollonian aesthetic principles; Dionysus symbolized what was untamed, frantic, and irrational, whereas Apollo symbolized what was logical and ordered.

This notion of a competition or conflict between Dionysus and Apollo has been labeled a “modern myth” since it was invented by modern philosophers such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Nietzsche and is not present in ancient texts.

Nevertheless, the acceptability and widespread acceptance of this notion in Western society has been so strong that its undercurrent has impacted the conclusions of Classical scholars. Nietzsche also believed that the earliest forms of Greek tragedy were completely based on Dionysus’ suffering. Other theories put Dionysus’ emotionality front and center, emphasizing the god’s joy, horror, or madness. Vyacheslav Ivanov, a poet, built on the Dionysian theory, linking the origins of literature, particularly tragedy, to archaic Dionysian mysteries. Dionysus’ suffering, according to Ivanov, “was the distinguishing characteristic of the cult”, much as Christ’s suffering is crucial for Christianity.

Sigmund Freud requested that his ashes be stored in an Ancient Greek vase decorated with Dionysian motifs from his collection, which is still on display at London’s Golders Green Crematorium.

The Parallels of Dionysus’ Mythology and Christianity

In ancient Rome the cults of Dionysus/Bacchus and Christ shared many core attributes. Both were very popular amongst women and those who lacked political and economic power. Both were considered to represent a significant threat by the Roman authorities due to their advocacy of discarding the laws of man for those of a higher power. Both celebrated the death and resurrection of a god who was fully divine, but born from a human woman. And lastly, both had rituals where the body of the savior was symbolically ingested by the faithful in the form of wine and bread.

In terms of myth, numerous academics have related stories about Christ and Dionysus as enduring models of the dying-and-rising deity.

Though, it has been noticed that the circumstances of Dionysus’ death and resurrection differ considerably from those of Jesus, both in substance as well as symbolically. Some scholars maintain that by the 4th century CE, the Dionysian religion had evolved into strict monotheism; combined with Mithraism and other denominations, the cult represented a type of pagan monotheism in direct conflict with Early Christianity throughout Late Antiquity.

Wool and linen tapestry depicting Dionysos (250-450 CE); Kunsthistorisches Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wool and linen tapestry depicting Dionysos (250-450 CE); Kunsthistorisches Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Another similarity can be observed in The Bacchae when Dionysos is brought before King Pentheus on allegations of proclaiming divinity, which is paralleled to the New Testament scenario of Jesus being examined by Pontius Pilate. A number of academics, though, reject this comparison, arguing that the encounter between Pentheus and Dionysus ends with Pentheus dying, while Jesus’ trial concludes with him getting put to death. However, in early Christian mythology, the idea of the willful non-believer who would eventually be punished by the god, took the form of representatives of the Roman state who would not accept Christ as a god, and in their ignorance martyred true believers.

Philosophers from the 16th century onward, particularly Gerard Vossius, studied the connections between the myths of Dionysos and Moses.

Such parallels may be found in the details of Poussin’s paintings. According to John Moles, the Dionysian cult inspired early Christianity, particularly how Christians perceived themselves as a new religion based on a savior god. He claims that Euripides’ The Bacchae profoundly affected the story of Christian origins. Moles also claims that Paul the Apostle could have based his description of the Lord’s Supper in part on ceremonial meals carried out by Dionysian cult members.

Dionysos, the deity of fertility and wine, was subsequently also regarded as a patron of the theatrical arts. He invented wine production and popularized viticulture. He had a split personality; on the one hand, he offered joy and divine ecstasy; and on the other, he displayed violent and blinding anger. Dionysos was the only deity born both from a mortal mother and the body of a god. Dionysos was connected with various major Greek mythological themes and became one of the most influential gods in everyday life. One aspect was rebirth after death; his dismemberment and subsequent rebirth were symbolically replicated in viticulture, where vines must be severely trimmed back before going dormant in winter in order to grow fruit. It is due to this connection with the idea of death and rebirth that many people draw parallels between the myths of Dionysos and Christ.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Dionysos the God of in Greek Mythology?

In Greek mythology, he is primarily regarded as the god of wine. Yet, his domain does not end there, as he is also the god of many other aspects of Greek life such as theater. He is also a god of male fertility and festivities, and plays a role in religious ceremonies aimed at producing feelings of ecstasy among celebrants.

What Is Dionysos’ Roman Name?

Dionysos was also know as Bacchus after the word used to describe the frenzy he induced in his worshipers. The ancient Roman god of wine Liber Pater came to be known as Bacchus, reflecting the growing popularity of the Dionysian festival, the Bacchanalia. Dionysos would have a lasting impact on mythology throughout the ages due to his various roles. His role as a god that died and was reborn, as well as being born to a from a god to a mortal woman, has made many people find similarities between his stories and that of the Christian faith.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.