Greek God Crius – Ram-Headed Pillar of the Southern Skies

The Greek god Crius is a vague mover in ancient Greek mythology, known only through associations and ancient history. As one of the Titan brothers who castrated Uranus and ruled during the Golden Age, Crius has been a mystery for centuries. Come with us as we explore the various speculations surrounding the Titan Crius, from the celestial motions of the seasons to the ties and tides of war below!

The Pillar of the South: The Greek God Crius

| Name | Crius (Also known as Krios or Megamedes) |

| Gender | Male |

| God of | The southern heavenly pillar and constellations |

| Personality | Truculent and virile |

| Consorts | Eurybia |

| Children | Astraios, Pallas, Perses, and sometimes Python |

| Parents | Gaia and Uranus |

Crius, the Latinized version of the original Greek name Krios, was believed to belong to the group of ancient gods known as the Titans, and is one of the twelve primary godly offspring of mother Gaia and father Uranus known by this title. The Greek god Crius’s surviving classical references are few, and usually restricted to being a Titan of the Golden Age and his role as the origin of his more notable descendants.

Like many Titans he had very little cult presence, however, his legend has much speculation and associations with the South, stars, and combat.

The Titan Crius’ Background

The Greek god Crius is also known by the Greek name “Krios” or “Kreios”, with Crius being the Latinized version. The name Krios is thought to translate from ‘krios’ the Greek word for ‘ram’ and has much debated etymology, while Kreios is suggested to derive from ‘kreiôn’ meaning ‘ruler’. He is also referred to as the father of Pallas by the name Megamedes, which is derived to mean ‘great lord’ from the words ‘megas’ and ‘mêdos’), in the Homeric Hymn 4 to Hermes (7th – 4th century BCE).

As one of the defeated Titan sons of Gaia and Uranus, he gets little reference in surviving classical records, and his origins are thus largely speculative.

The collective roles of Titans are to explain the origins of many concepts as well as the authority and genealogy of their successors, the Olympian gods. It has been proposed that the Titans and the pillars upholding the sky in particular, of which Crius is one, are taken from Near East mythology. Crius has gained popular associations with the south, stars, and war, through speculation surrounding the meaning of his name and the domains of his descendants.

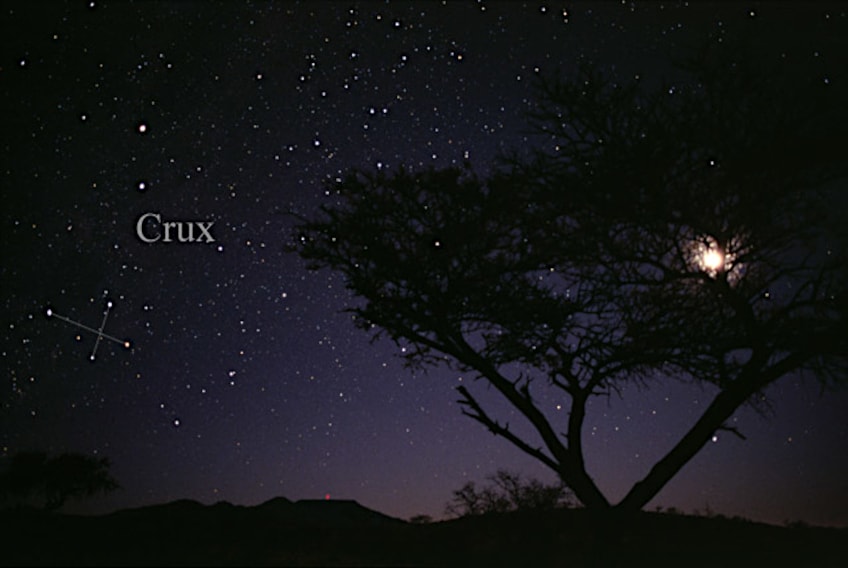

The constellation Crux also known as the Southern Cross as seen from the southern hemisphere; Till Credner, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The constellation Crux also known as the Southern Cross as seen from the southern hemisphere; Till Credner, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Crius’ Genealogical Connections

The Titan Crius was named in Hesiod’s list of the Titan offspring of the primordial earth goddess Gaia, and the primordial sky god Uranus. His siblings include the eleven other Titans listed in Hesiod’s Theogony (8th-7th century BCE) and most other established traditions, namely Hyperion, Iapetus, Koios, Kronos, Mnemosyne, Oceanus, Phoebe, Rhea, Tethys, Theia, and Themis.

Crius’ sibling groups include those of the hundred-handed Hecatoncheiries, the one-eyed Cyclopes, The Furies or Erinyes, the Gigantes, the Ourea, and the tree nymphs the Meliae.

Crius has many more siblings and half-siblings in mythology, from the beautiful Aphrodite to the monstrous Typhon. They also include names such as Nereus, Thaumus, Phorcys, Ceto, Python, Pontus, and Eurybia. His only known consort was his half-sister Eurybia, the daughter of Gaia and a pre-olympian sea-god Pontus who was himself a son of Gaia. By the goddess Eurybia, Crius is the father of three sons named Astraeus, Perses, and Pallas. In the description of how Pytho, also known as Delphi, got its name in Pausanias’ Description of Greece (2nd century CE), an alternative myth to Apollo striking down its guardian Drakon is listed. Instead of Python the Drakon, the one slain by Apollo was a violent “son of Crius” of power in Euboea, who went pillaging the houses of gods and wealthy men alike until the Delphians sought Apollo’s aid.

Apollo shoots Python, the Dragon by Hendrick Goltzius after Hendrick Goltziusschrijver (1589); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Apollo shoots Python, the Dragon by Hendrick Goltzius after Hendrick Goltziusschrijver (1589); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Through his three sons, the Titan Crius has some notable descendants in Greek mythology. Astraeus is the father of the Anemoi, the four winds, and the gods Astraea, Eosphorus, and Hesperus. Through Perses, Crius is the grandfather of Hecate, and in one myth Chariclo. His son Pallas fathered the gods Bia, Kratos, Nike, Zelus, and in some interpretations, Scylla, Selene, and Eos.

The Greek God Crius in Mythology

Classical references to Crius are few amongst the surviving literature, and thus his role in Greek mythology is by and large conjectural. Similar to other Titans, his role is mostly as an embodiment of a cognitive or geographical concept, and an ancestor to the more popular generation of Greek gods.

The Titan Crius

Titans in Greek mythology serve to populate the narrative prior to the Olympian gods, explaining concepts and geographical features as the ancient Greeks understood them. They also serve as the origin of the lineage, domains, and general authority of the Olympian gods who overthrew the Titans for rulership of the cosmos. The Titans, of which Crius is one, came into power themselves when Cronus castrated the sky father Uranus at the behest of their mother Gaia.

The earth goddess was suffering because the sky god kept pushing her children back into her as soon as they were born.

According to established tradition, Crius and his Titan brothers assisted Cronus in this task, by going to the corners of the world and holding Uranus down when he came to couple with Gaia. Cronus became king of the Titans and cosmos, while his brothers were a part of his reign, a period of paradise and plenty known by some as the Greek Golden Age.

The Golden Age by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1862); Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Golden Age by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1862); Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

One myth holds that his four brothers, Crius (Krios), Coeus (Koios), Hyperion, and Iapetus, were given great honors. They became known as the four pillars that upheld the heavens separate from the earth, a notion speculated to be adopted from Near East mythology. Crius was attributed to be the southern of these heavenly pillars generally, with Hyperion in the East, Iapetus in the West, and Coeus in the North. While no sources are named for this myth it has made its way into common thought surrounding the Titan Crius.

Crius fought alongside his brother Kronos against Zeus during the 10-year Titanomachy, and for his part in the war was imprisoned in the tortuous abyss of Tartarus with the other male Titans.

He may have been part of his mad brother Ceous’ doomed escape from the abyss, detailed in the Argonautica 3 (1st century AC) but was not named. According to descriptions of the lost play Prometheus Unbound, Zeus eventually released the Titans, presumably including his uncle Crius, and granted them clemency.

Crius the Ram Constellation

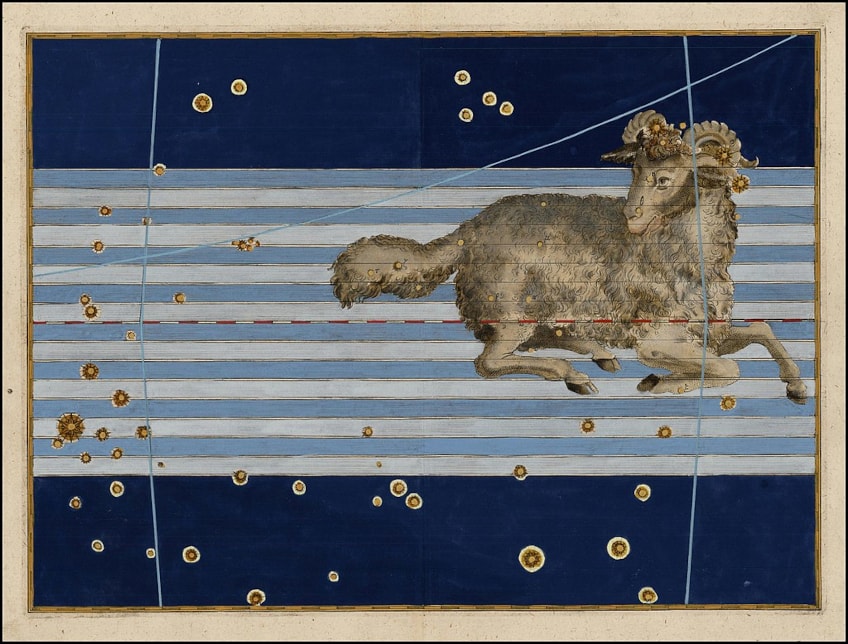

The Titan Crius was known by the Greek name Krios, which has been translated from the Greek word for ‘ram’. An interpretation of an excerpt of Nonnus Dionysiaca 38 (5th century CE) seems to refer to Krios in the capacity of “the Ram” constellation known commonly as Aries.

The constellation is a southern one, and its appearance at the beginning of spring placed it at the start of the new calendar years of ancient Rome, however ancient Greek calendars themselves were incredibly diverse in their regional variants, foundational uses, and frequent changes.

It is also possible Crius as Aries would herald the “fighting season” of the ancient world, the months of fairer weather that began in spring and ran through summer which were favored for their general lack of harsh and cold weather. The war-like connotations may continue with his sons Perses “the destroyer”, and Pallas “the spear-bearing” father of the personifications of might, power, victory, and zeal or emulation, known as Bia, Kratos, Nike, and Zelus respectively.

Astrological chart showing the constellation of Aries by Johann Bayer (1603); Johann Bayer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Astrological chart showing the constellation of Aries by Johann Bayer (1603); Johann Bayer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Come commentary has linked Krios as the Aries constellation with the Titan’s brother Hyperion, the father of the sun, moon, and dawn. It is suggested that much like Hyperion brought order to the cycle of days, his brother Crius brought order to the cycle of years, as the rising constellations and stars were sometimes used to measure the parts of the year. His sons could also be loosely linked to this idea. The star-god Astraeus may have links with Aristaeus who brought cooling winds in the heat of midsummer that was heralded by the Dog-star Sirius. Perses may also have had ties with Sirius, like his hound-associated daughter Hecate, or the constellation Perseus. Pallas, whose skin became a type of goatskin aegis for Athena, is connected with the storm season herald goat-star Capella or Auriga. In this way, Crius is connected to seasonal stars and winds and is proposed to be the ancient father and god of constellations and their role in measuring and ordering the seasons.

His chthonic role in mythology can be used as either a detraction from his non-classical celestial association or support through the idea of constellations normally passing below the horizon in Greek cosmology.

The Titan Crius’ role as the “ram” god and his descendants possibly connecting with animals, like the “goat-skinned” Pallas and the canine associations of Perses and Hecate, has impacted his image directly. Some popular non-classical descriptions of Crius include bestial attributes, such as having horns or a ram’s head. While his connection with the Aries constellation and ram imagery may not be remarked upon in any surviving writings, the associations have become a part of his mythos in this modern day.

The Surviving Legacy of Crius

Very little survives of most Titans of Greek myth, and it has been speculated that many were simply names used to fill holes in group numbers and family trees. Most have known descriptions or worship, which is befitting their place as ‘bygone’ gods of a previous ancient era. The Titan Crius is a prime example of this limbo in mythology. As far as we have found, classically Crius is rarely if ever mentioned outside of listings of the twelve Titan children of Gaia and Uranus, or referrals to his relations.

No descriptions of the god have been made commonly known, nor have any detail of Crius’ symbols, his worship, sacred places, or local customs involving him.

A Titan in Greek mythology is classed as an ancient being, powerful and nebulous as the concepts and primordial forces they embody. Male Titans in particular gain a bias of being wilder and more willing to fight than the succeeding Olympians, with their depictions that of muscular and imposing forms.

The Titans were considered wild and unruly gods; artist’s impression

The Titans were considered wild and unruly gods; artist’s impression

Crius through his association with the ram constellation, has gained a popular imagery of ram features, such as horns or a ram’s head, as well as the associated symbolism of strength, virility, and a defiant boldness that may sometimes err into brashness. The current ideal of Crius is one of determined power, energy, and fierceness, only emphasized when taken alongside his grandchildren embodying energizing concepts of force, might, victory, and zeal. We have no definite answers on Crius’ symbols nor any mentions in cult traditions of his own or his relatives, but his colloquial associations with the ram and southern heavenly pillar means that either of them could count as one of Crius’ symbols.

Aside from Krios, other names for Crius, namely Kerius and Megamedes, translate to ruler and great ruler, which adds to the Titan’s capacity for dominion and overall imposing nature.

Other associations of Crius include a tributary of the Akhaian river Hermos described in Pausanias’ Description of Greece, suggested to be connected to the Lydian river of the same name. Lydia was a place commonly associated with Titans, most notably that of Crius’ nephews, Atlas and Prometheus. Karystos of Euboea is another semi-divine ancient figure with possible ties to Crius. Crius’ modern affiliations are largely that of popular fictional portrayals of Greek mythology, such as appearing in The Coming of The Titans (1962), and The Last Olympians written by Rick Roirdan.

Lessons Learned from the Titan Crius

Crius is a tricky figure, in that we do not get a glimpse of him through any interactions in mythology or preference in cult writings. A once great god, he was defeated and left to disappear from the annals of history more for the crime of complacence rather than any detailed contempt.

One lesson that could be taken from our Titan of constellations and seasonal order, is a dual cautionary tale and reminder of hope.

Crius as Aries rises from beneath the horizon to begin the spring, a time of renewal, of energy, and the endless hope of possibility. Crius as the son of Uranus rose to rule the cosmos when he answered his brother’s call and was a pillar of the most peaceful age of Greek mythology. Crius as the brother of Kronos fell into Tartarus when he stood beside his brother against Zeus. Crius as the defeated Titan suffered centuries in the dark abyss of Tartarus, but his descendants roam powerful and free across the world, and in some myths walked free under the sky once more.

As demonstrated in the iconic final scene of the film Planet of the Apes, even the greatest powers will eventually fall; artist’s impression

As demonstrated in the iconic final scene of the film Planet of the Apes, even the greatest powers will eventually fall; artist’s impression

The story of Crius shows that empires rise and fall, and good and bad times come and go like the seasons.

You may be thriving now but the winds may change at any time. You may have a good relationship with someone now, but that does not mean you are obligated to stick with them if their behavior becomes harmful to you. Crius shows that just as the golden days cannot last, neither can the dark ones, and that stars may fall but they may also rise again with time.

Much like Aries rises to begin each year and brings the hope of wars that might be won, anything can happen in the future if you are determined enough to pursue it. Whether it be energetic resolutions for the new year, or quiet dedication to moving forward from your situation, Crius shows that tomorrow is not set in stone and that all things end in time, for good or for ill. In life you have the endless capacity for change, but only if you make the decision to try and dedicate your energy to it. Be bold, be brave, and be belligerent in your pursuit of fortunes, lest you languish in an abyss of your own making.

The Greek god Crius is a figure of Greek mythology who is believed to be a Titan who helped usher in the Golden Age, was the southern pillar upholding the very heavens, and was the ancestor of stars and powerful forces of nature and emotion. The Greek god Crius is speculated to be the origin of ancient seasonal order, and the constellations that measure and herald them. This ghost of a god has little classical relevance beyond his relations, but the modern ram-god is a character of power and energy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Crius the God Of?

Crius’ domain has been speculated to be the Greek god of constellations. He is associated with the springtime constellation Aries, the ram, and is father and grandfather to many star-associated gods. He is also considered to be the southern pillar upholding the heavens, though this may be more metaphorical for his role in ushering in and ruling during the Greek Golden Age.

What Does Crius Mean?

The name Crius is a Latin spelling of the Greek name Krios, from the Greek word krios meaning ram whose etymology is still currently debated, or Kreios from the word kreiôn, which translates to ruler. Another name attributed to Crius is Megamedes, the father of Pallas, taken to mean great lord from the words megas and mêdos.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.