Famous Renaissance Sculptures – Highlights from Italy and Spain

In the early to late Renaissance art period in Italy, Renaissance sculptors had actual examples of ancient Greek sculpture to be inspired by and to draw from – the very work they adored – whereas the Renaissance painters had no ancient paintings to reference. While sculptures of the Renaissance period relied heavily on the works that came before them, they also offered new themes and techniques. Italian Renaissance sculpture in the 15th to 16th centuries was largely commissioned by royal families, the church, and nobility. Today, we shall explore the famous Renaissance sculptures that set new standards in the medium.

Italian Renaissance Sculpture

During the 15th century, Italy was made up of several regional entities, such as the Duchies of Savoy and Milan, as well as the Republics of Genoa, Venice, Florence, and Siena. Furthermore, the States of the Church controlled a substantial portion of Central Italy, whereas the Kingdom of Naples controlled the entirety of Southern Italy, including Sicily. In general, these territories were controlled by individuals and families, many of whom were prominent supporters of Renaissance artworks, including painting and sculpture. The Gonzagas of Mantua, the Visconti and Sforza of Milan, the Este of Ferrara and Modena, the Montefeltro of Urbino, and the famous Medici family of Florence were among the most powerful reigning families.

Sculptures of the Renaissance Characteristics

Individualism defined painting and sculpture almost from the beginning, as advancement became increasingly less a representation of movements and more about the works of individual creators. Naturalism was another major aspect of late Renaissance art. This was shown in sculpture with a rise in modern topics, as well as a more naturalistic treatment of proportionality, fabric, perspective, and anatomy. The revival of classical themes and styles was a third element.

Since Rome’s fall in the 5th century, Italy never totally abandoned Greek sculpture, nor has it been able to disregard the visible bulk of Roman remains. However, it was the excavation of a sculptural group depicting the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons killed by snakes in 1506 that sparked a revived interest in classical art.

The famous sculpture of Laocoön and his Sons that reignited interest in ancient art and inspired the sculptors of the Renaissance has been dated to between 27 BCE and 68 CE

The famous sculpture of Laocoön and his Sons that reignited interest in ancient art and inspired the sculptors of the Renaissance has been dated to between 27 BCE and 68 CE

The rebirth of classicism in the sculptures of the Renaissance started during the time of Nicola Pisano and was popular all through the 15th century. Gothic traditions persisted for most of the early renaissance, but they usually took on a more classic appearance. Only in the High Renaissance period did classicism totally take hold.

The primary focus of Italian Renaissance sculpture was religion. Perhaps less so than during the Romanesque and Gothic eras – after all, Europe was getting wealthy – but Christianity continued to be a significant presence in the lives and artworks of both rulers and peasants.

Famous Renaissance Sculptures

Sculpture themes were nearly identical to those employed in early Renaissance artwork. Subjects for religious works were almost usually drawn from both the Old and New Testaments. If the Mother and Child is the most popular topic, other prominent subjects include events from Christ’s or Mary’s life, as well as Genesis tales. With the exception of Putti and Cupids, decorative themes of classical heritage were occasionally integrated into religious artworks. However, throughout the High Renaissance, themes diversified, and themes for non-church sculptures could include scenes from ancient mythology, portraiture of (or themes associated with) the patron involved, and Biblical themes.

Tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici with Night and Day (1536 – 1531)

Tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de’ Medici with Night and Day (1536 – 1531)

Saint Matthew (1420) by Lorenzo Ghiberti

| Sculptor | Lorenzo Ghiberti (born Lorenzo di Bartolo) (1378 – 1455) |

| Date Completed | 1420 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 270 |

| Current Location | Museo di Orsanmichele, Florence, Italy |

Saint Matthew by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1420); Lorenzo Ghiberti, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Saint Matthew by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1420); Lorenzo Ghiberti, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Lorenzo Ghiberti finished many bronze statues for the Orsanmichele in Florence, one of which is St. Matthew. To mirror the continuity of the outside niches on this structure, they are all around the same height. To keep the sculptures intact for decades to come, they have now been brought indoors. Four years after it was commissioned in 1419, the sculpture was finished. At that time, the sculptor was in great demand and frequently had many projects going at once. His first batch of bronze doors, which were also made in Florence, significantly increased his notoriety and spurred him to enlarge his workshop.

Ghiberti intentionally portrayed St. Matthew with his weight disproportionately on one side to simulate mobility.

David (c. 1440s) by Donatello

| Sculptor | Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (1386 – 1466) |

| Date Completed | c. 1440s |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 158 |

| Current Location | Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy |

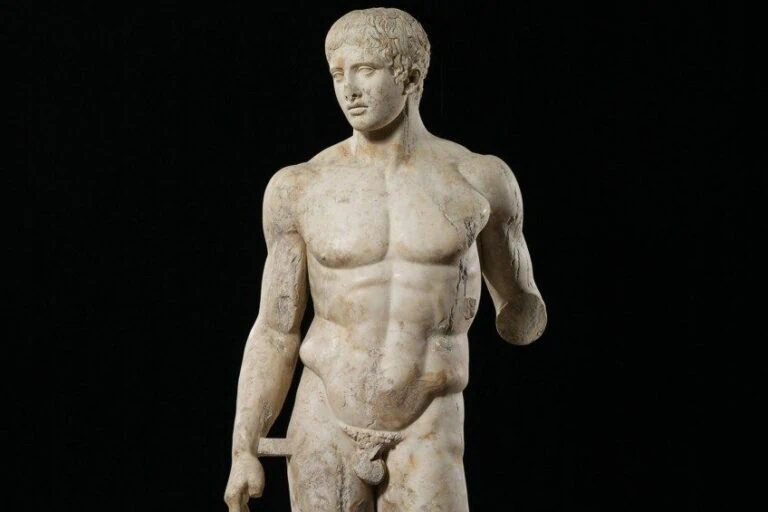

There are various younger variations of Donatello’s David statue, which was created during the first 10 years of the 15th century. Donatello’s subsequent sculpture was the very first freestanding bronze sculpture of the Renaissance era, as well as the first male naked figure since classical Greek statues. The bronze monument was controversial throughout the Renaissance and afterward because of the sexual undertones some experts saw.

David by Donatello (c. 1440’s); Rufus46, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

David by Donatello (c. 1440’s); Rufus46, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The statue depicts the evolution of his approach and vision from his youth’s considerable Gothic influence, defined by decoration and grace, to his latter years’ more realistic style, which was less exaggerated and more natural. The distinctions between Donatello’s first and second sculptures demonstrate the progression of the artist’s humanist outlook, which is typical of the Renaissance awakening. As such, the bronze exemplifies the fusion of classical inspirations with nudity and naturalism, such as the Renaissance sculptor’s decision to depict David as the developing adolescent of the Bible tale instead of a traditional hero.

Christ and St. Thomas (1483) by Andrea del Verrocchio

| Sculptor | Andrea del Verrocchio (1435 – 1488) |

| Date Completed | 1483 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 230 |

| Current Location | Orsanmichele, Florence, Italy |

The giant statue by Verrocchio was produced to be used as one of the 14 niches on the facade of the Orsanmichele in Florence, Italy. It has since been recast, and the original sculpture has been moved within the building, which has become a museum. It features Thomas’s Incredulity, a theme that has been used to express many theological concerns in Christian artwork at least since the 5th century. Thomas the Apostle had to personally feel the wounds to be convinced that Christ had indeed risen from the dead.

Christ and St. Thomas by Andrea del Verrocchio (1483); Dimitris Kamaras from Athens, Greece, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Christ and St. Thomas by Andrea del Verrocchio (1483); Dimitris Kamaras from Athens, Greece, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Donatello built the accompanying niche for his Saint Louis of Toulouse (1413) but when the niche was purchased by the Tribunale di Mercanzia, who ordered the Verrochio piece, the figure was moved to Santa Croce. The piece was Orsanmichele’s debut narrative composition. The craftsmanship of Verrocchio reveals a profound knowledge of the form and subject matter of classical sculpture.

Since the figures would only be visible from the front, they were not cast with backs. By saving money on bronze, which cost approximately 10 times more than marble, the sculpture became easier and lighter to fit into the niche.

Moses (1515) by Michelangelo

| Sculptor | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475 – 1564) |

| Date Completed | 1515 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 235 |

| Current Location | San Pietro, Vincoli, Rome, Italy |

Giorgio Vasari described the statue, noting that it was seated in a solemn posture, with Moses laying one arm on the tablet and the other on his long, lustrous beard, the hairs of which were so silky and soft that the iron chisel appeared to have turned into a brush. The handsome face, like that of a saint or a strong ruler, seemed to require a shroud to conceal it, so magnificent and bright it was, and so beautifully had the artist depicted in marble the purity with which the Lord had bestowed his holy visage.

Moses by Michelangelo for the Tomb of Pope Julius II (1513); Luca Casartelli, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Moses by Michelangelo for the Tomb of Pope Julius II (1513); Luca Casartelli, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The biblical scriptures only refer to Moses having “horns” when he returned to the Hebrew people after the second giving of the Law, thus scholars have noticed that Moses is pictured carrying blank tablets, which God had directed Moses to construct in preparation for the second imparting of the Law. They believe that the monument captures the scene from Exodus 33 where Moses first meets God.

Cristo Della Minerva (1521) By Michelangelo

| Sculptor | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (1475 – 1564) |

| Date Completed | 1521 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 205 |

| Current Location | Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, Rome, Italy |

This was a long-overlooked sculpture from the Italian High Renaissance, created by Michelangelo, one of the masters of sculpting. Metello Vari, a Roman nobleman, commissioned the piece in 1514 and requested that the naked Christ carry the cross in his hands. The statue was begun in Michelangelo’s workshop but was discarded in 1515 after Michelangelo discovered a dark vein in the marble. In 1519, Michelangelo rushed to complete a fresh version in order to fulfill his half of the commission arrangement.

Cristo della Minerva by Michelangelo (1521); My Past, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Cristo della Minerva by Michelangelo (1521); My Past, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

He began work on the statue in Florence and eventually delegated the finishing touches to his Rome-based pupil, Pietro Urbano. Unfortunately, Urbano ruined the sculpture, so the sculptor had to locate another substitute to complete it. He enlisted the help of Federico Frizzi this time.

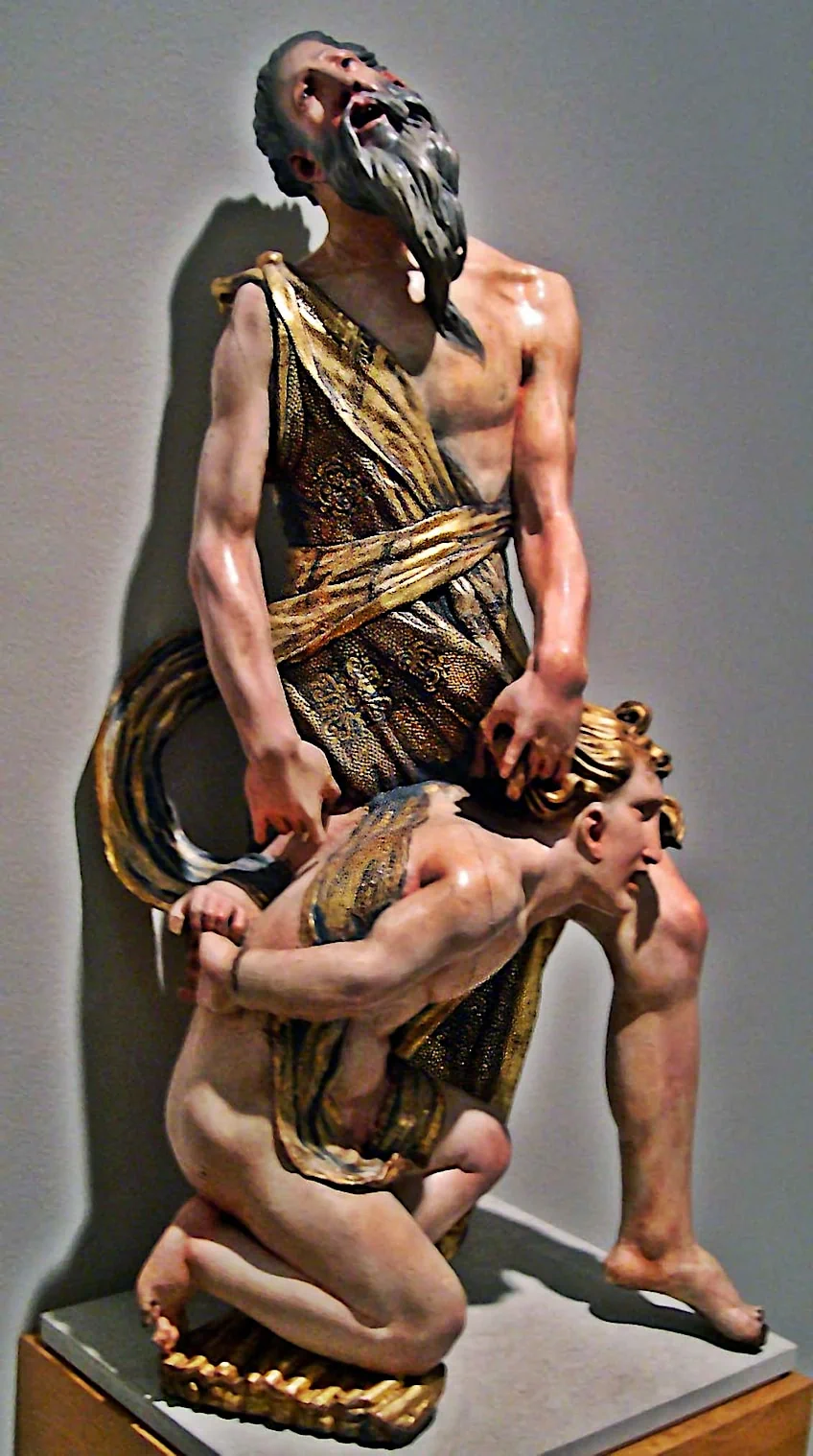

Abraham and Isaac (1532) by Alonso Berruguete

| Sculptor | Alonso Berruguete (1490 – 1561) |

| Date Completed | 1532 |

| Medium | Polychromed wood |

| Dimensions (cm) | 89 x 46 x 32 |

| Current Location | Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid, Spain |

Abraham and Isaac by Alonso Berruguete (1532); Locutus Borg, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Abraham and Isaac by Alonso Berruguete (1532); Locutus Borg, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Berruguete created works for a wide range of rich clients around the Iberian Peninsula. While numerous renderings of the famous biblical story have been done with theatrical flair, Berruguete concentrates on the subjects’ strong emotions. Berruguete masterfully conveys Abraham and Isaac’s moment of despair before their moment of deliverance when an angel chooses to halt the sacrifice. Despite being made of wood, the statue is painted in gorgeous polychrome hues and has superb technical execution. Estofado was used to create the curtains around Abraham’s body and Isaac’s torso.

Berruguete and his workmen built the figure, which was then covered in gold leaf and polished.

Hercules and Cacus (1534) by Baccio Bandinelli

| Sculptor | Baccio Bandinelli (1493 – 1560) |

| Date Completed | 1534 |

| Medium | White marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 73 |

| Current Location | Piazza della Signoria, Florence, Italy |

The republican government of Florence, directed by Piero Soderini, ordered this work by Florentine sculptor Baccio Bandinelli as a companion piece to David to commemorate the fall of the Medici. The colossus was initially handed to Michelangelo to accompany the David statue, but once the Medici dynasty returned from exile in 1512 and once more in 1530, they used it as a symbol of their regained dominance.

Hercules and Cacus by Bartolommeo Bandinelli (c. 1525-1534); Morio, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hercules and Cacus by Bartolommeo Bandinelli (c. 1525-1534); Morio, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Although vocal and written critiques of the marble were offered during accounts of its presentation in 1534, the majority of these critiques were not aesthetic and rather targeted at the Medici family for collapsing the Republic. The fact that some of the authors of these harsh lines were put in prison by Alessandro de Medici further suggests a political agenda. Benvenuto Cellini and Giorgio Vasari, both supporters of Michelangelo and competitors of Bandinelli for Medici support, were the two fiercest detractors.

Vasari bemoaned the change in designers and hands from Michelangelo to Bandinelli.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545) by Benvenuto Cellini

| Sculptor | Benvenuto Cellini (1500 – 1571) |

| Date Completed | 1545 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 71 x 24 |

| Current Location | Loggia Dei Lanzi, Piazza Della Signoria, Florence, Italy |

Benvenuto Cellini, the famed goldsmith, served under the patronage of Cosimo de Medici, the most prominent individual in Florence and the head of the significant banking dynasty. In one of Florence’s most important piazzas, he created a sculpture of Perseus carrying the severed head of the terrifying Medusa. The sculpture has numerous noteworthy aspects aside from its remarkable beauty. For one thing, it is made of a solitary bronze cast instead of being assembled from many sections, as most bronze statues were in the period.

Perseus with the Head of Medusa by Benvenuto Cellini (1545-1554); Bradley Weber, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Perseus with the Head of Medusa by Benvenuto Cellini (1545-1554); Bradley Weber, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Second, the sculpture’s fundamental foundation is part of the larger design, since the hero stands atop Medusa’s slain body. Cellini’s personal reflection may also be seen in the rear of Perseus’ helmet. This, like Jan van Eyck’s artwork, invites the observer to reflect on the artist’s involvement in his creation. It also alludes to the myth of Perseus, who defeated the Gorgon by staring at her in the mirror of his shield.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman (1583) by Giambologna

| Sculptor | Giambologna (1529 – 1608) |

| Date Completed | 1583 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 410 |

| Current Location | Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence, Italy |

Giambologna, a Flemish artist and craftsman, created this enormous and elaborate marble Italian Renaissance sculpture. It was sculpted around 1583 when the sculptor was studying at Rome’s esteemed Accademia Delle Arti del Disegno, which was funded by Cosimo I de Medici. Giambologna received a great deal of acclaim during his lifetime, and this artwork is frequently said to be his best. Since August 1582, it has been located at the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence. The sculpture has a figura serpentina design.

Abduction of a Sabine Woman by Giambologna (c. 1579-1583); Rufus46, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Abduction of a Sabine Woman by Giambologna (c. 1579-1583); Rufus46, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Three nude people can be seen, including a younger man in the center who appears to have taken a woman from an old man below. It is said to be modeled on the Sabine Women event from Rome’s early history, in which the city’s males perpetrated the rape of young women from neighboring villages.

It was Giambologna’s first sculpture for Tuscany’s Francesco de’ Medici, and it was created in the Mannerist style popular during the period of the Italian High Renaissance. It features three full figures and was sculpted from one piece of white marble.

Apollo and Daphne (1625) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Sculptor | Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598 – 1680) |

| Date Completed | 1625 |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 243 |

| Current Location | Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy |

Bernini’s sculpture, carved from a solitary block of marble, conveys all of the action and romance of the original narrative. The lustful Roman deity Apollo attempts to abduct the beautiful Daphne, but she is unexpectedly transformed into a laurel tree at the last moment. Bernini depicts the transition in a single frame. The subject and medium are clearly contrasted. Despite being made of solid, unforgiving rock, the sculpture is dynamic and fluid.

Apollo and Daphne by Bernini (1625); Architas, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Apollo and Daphne by Bernini (1625); Architas, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The imprint of his hand on her waistline (now tree bark), the spreading of her fingers into leaves, and the flowing robes barely covering the bodies all suggest movement and delicacy.

Bernini’s statue exemplifies the technical proficiency of the sculptures of the Renaissance, classical inspiration, and aesthetic creativity.

Although Bernini’s fame declined after his death, appreciation for the sculpture persisted. Historians of today describe it as a magnificent work of art that is infused with a force that emanates from the tips of the laurel leaves, Apollo’s hand, and the drapery.

The works of ancient antiquity and its mythology served as the foundation and model for famous Renaissance sculptures, which combined a new concept of humanist ideas and the purpose of sculpture in art. The lifelike portrayal of the nude human body, just like in Greek sculptures, was achieved with a highly developed method, owing to the rigorous research of human anatomy. In Italy, secular and religious subjects coexisted equally; in other nations, such as Germany and Spain, religious themes predominated.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are the Characteristics of the Sculptures of the Renaissance?

The human form symbolized ultimate beauty, with the well-defined mathematical connection between the components, and the contrapposto was utilized continually from Michelangelo to Donatello. It was during this period that Italian Renaissance sculpture was practically liberated from the architectural framework, reliefs were created using point of view guidelines, and characters were depicted with striking expressions, creating a sense of fantastic terribilità in the emotions conveyed in Michelangelo’s statues, such as the face of his David (c. the 1440s).

What Defined Late Renaissance Art?

The Late Renaissance, often known as the Mannerism period, is distinguished by works that used previous works of art as models. The human body was their major subject, which was frequently stretched, exaggerated, beautiful, and organized in twisted configurations. This was the court’s aesthetic, and many of the works include hidden messages and pictorial games intended to challenge the spectators’ intellect.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.