Egyptian Artifacts – Famous Antiquities From Egyptian History

When it comes to archaeological discoveries, the long and rich history of ancient Egypt means that very few cultures can match the number and variety of Egyptian artifacts. For over 4000 years, the ancient Egyptians developed some of the most captivating and exquisite objects and monuments the world has ever seen, many of which have remained remarkably well-preserved to the present day. The creative designs of ancient Egypt artifacts were primarily influenced by their intense devotion to the gods (which included the pharaoh). Egyptian sculptures and images were also used to represent the power of the pharaoh across Egypt, depict sacred spells and texts designed to protect and guide the dead, and narrate the tales of the aristocracy. Today, we will look at some of the most famous Egyptian artifacts and ancient Egyptian relics.

Exploring Famous Egyptian Artifacts

Egypt has a history that stretches back into the ancient era, and therefore, features many remarkable and enigmatic ancient Egypt artifacts that were discovered inside Egyptian tombs and monuments. Ancient Egyptian objects and structures reflect a cultural and religious obsession with achieving an absolute ideal of perfection, order, and symmetry. When studying ancient artifacts, it is important to remember that ancient artists created these objects for a range of purposes and with specific audiences in mind, which may not always be immediately apparent, or even logical to modern observers.

Let us now explore the most famous Egyptian artifacts, and by doing so, answer several questions, such as what is the oldest Egyptian artifact, what can we learn from ancient Egyptian artifacts, and which museum has the most Egyptian artifacts?

Narmer Palette (c. 3000 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 3000 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 3000 BCE |

| Medium | Siltstone |

| Site Found | Hierakonpolis, Aswan Governorate, Egypt |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

Narmer Palette (c. 3000 BCE); Cairo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Narmer Palette (c. 3000 BCE); Cairo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Some ancient Egyptian relics are so important to our comprehension of ancient society that they are really one-of-a-kind and irreplaceable. The gold mask of Tutankhamun was authorized to leave Egypt for international display; however, the Narmer Palette is so rare that it has never been allowed to travel outside Egypt.

This massive ceremonial artifact was discovered amid a set of holy instruments ritually deposited in a pit inside an early temple of the falcon deity Horus at the site of Hierakonpolis. It is one of the most important ancient Egyptian artifacts from the beginnings of Egyptian civilization.

The wonderfully carved palette is composed of polished greyish-green siltstone and is adorned with intricate low reliefs on both sides. These images depict a monarch, identified as Narmer, and a succession of unclear events that have been challenging to understand, leading to a variety of opinions about their significance. The excellent quality of the craftsmanship, its original role as a ceremonial item devoted to a deity, and the richness of the artwork all imply that this was an important object, yet a reasonable interpretation of the images has remained elusive.

Statue of Djoser (c. 2600 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 2600 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 2600 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone |

| Site Found | Saqqara, Egypt |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

Statue of Djoser (c. 2600 BCE); Jon Bodsworth, Copyrighted free use, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of Djoser (c. 2600 BCE); Jon Bodsworth, Copyrighted free use, via Wikimedia Commons

Around 2650 BCE, King Djoser governed Egypt during the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Djoser was said to be the first pharaoh to spend his whole reign at Memphis rather than touring between palaces. He also stretched Egypt’s power all the way from Sinai to Aswan.

Djoser is famous for two reasons.

First, he is renowned for rescuing Egypt from a seven-year drought by reconstructing the Temple of Khnum, the source of the Nile River. Second, and perhaps more crucially, Djoser is remembered for his burial monument, which was erected using stone blocks instead of mud bricks under the supervision of the renowned architect Imhotep.

Khafre Enthroned (c. 2569 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 2569 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 2569 BCE |

| Medium | Anorthosite gneiss |

| Site Found | Temple of Khafre, Egypt |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

Khafre Enthroned (c. 2569 BCE); Jon Bodsworth, Copyrighted free use, via Wikimedia Commons

Khafre Enthroned (c. 2569 BCE); Jon Bodsworth, Copyrighted free use, via Wikimedia Commons

This statue portrays King Khafre, the architect of Giza’s second biggest pyramid. It was discovered in his pyramid complex’s valley temple. The king sits gloriously on his throne, full of the grandeur of a Pharaoh. His throne is adorned on both sides with the sema-tawy, a symbol of Lower and Upper Egypt’s unification, indicating his reign over both parts of the kingdom. The deity Horus, in the shape of a falcon, perches on the backrest of the throne, behind the king’s head, spreading his wings in a protective gesture. The symmetrical pharaoh exhibits no motion or change, eliminating all movement and time to produce an everlasting stillness; his powerful physique and permanent attitude reveal no concept of time – Khafre is eternal, and his authority will persist even after death.

Egyptian idealized portraiture is not intended to capture human characteristics, but rather to depict the divine essence of an Egyptian pharaoh. The sculpture is entirely frontal, completely immovable, and completely calm: typical features of an Egyptian block statue.

Seated Statue of Menkaure (c. 2490 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 2490 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 2490 BCE |

| Medium | Indurated limestone |

| Site Found | Menkaure Temple, Egypt |

| Current Location | Metropolitan Museum, New York |

This incomplete Menkaure figurine was discovered in a sculptor’s studio near his pyramid’s valley temple. It was one of 14 incomplete king statuettes discovered there, all in various phases of the sculpting process. It shows the monarch in the usual stance, sitting with his hand placed flat on his thigh, palm down; his other hand, which has broken off, would have traditionally formed a fist. The statuette’s feet and the front half of the pedestal on which they sat were also damaged.

The monarch is seated on a block-like seat that, when finished, would have been engraved with the sematawy sign, which depicts Lower and Upper Egypt’s unification.

The statuette is constructed of high-quality hard limestone and has remnants of the figure’s initial blocking-out, which have been somewhat disguised by the first polishing of the surface. The musculature of the body has been emphasized, and the figurine depicts the contours of Menkaure’s square adult face, as seen in the massive alabaster and greywacke sculptures found throughout his temple. Menkaure is also the subject another remarkably well-crafted sculpture, where he is depicted alongside his queen.

Nefertiti Bust (1345 BCE)

| Artist | Thutmose (c. 14th century BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 1345 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone and stucco |

| Site Found | Tell el-Amarna, Egypt |

| Current Location | Neues Museum Berlin, Germany |

Nefertiti Bust (1345 BCE); Philip Pikart, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Nefertiti Bust (1345 BCE); Philip Pikart, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The sculpture created in 1340 BCE in the ancient Egyptian capital of Akhenaten, is a sculpted figure of Queen Nefertiti, who reigned with her Pharaoh Amenhotep IV, afterward known as Akhenaten. The bust was unearthed at the studio of Thutmose, a prominent sculptor who sculpted plaster busts of the ruling household. It is one of the most well-known artifacts from ancient Egypt.

Despite being found among statues of other members of the royal family, the Bust of Nefertiti is undoubtedly his most famous work.

The Bust of Nefertiti is famous not just for its bright hues and iconic portrayals of beauty, but also for its contentious past as an antique.

While historians lack written evidence, there is a complicated history around Nefertiti. The body of Nefertiti has yet to be discovered, limiting our knowledge of her to limited documented history and images of her found in ancient Egyptian art. The artwork was incomplete, and it was most likely merely a model constructed by Thutmose to utilize as a reference while he worked on other royal family items. While this sculpture was not intended to last, it is one of the few artifacts from ancient Egyptian art that has endured to inform us about a vivid history.

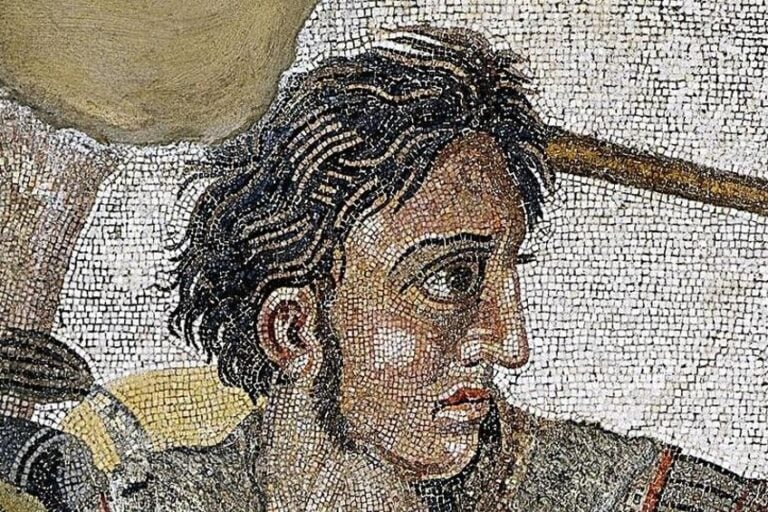

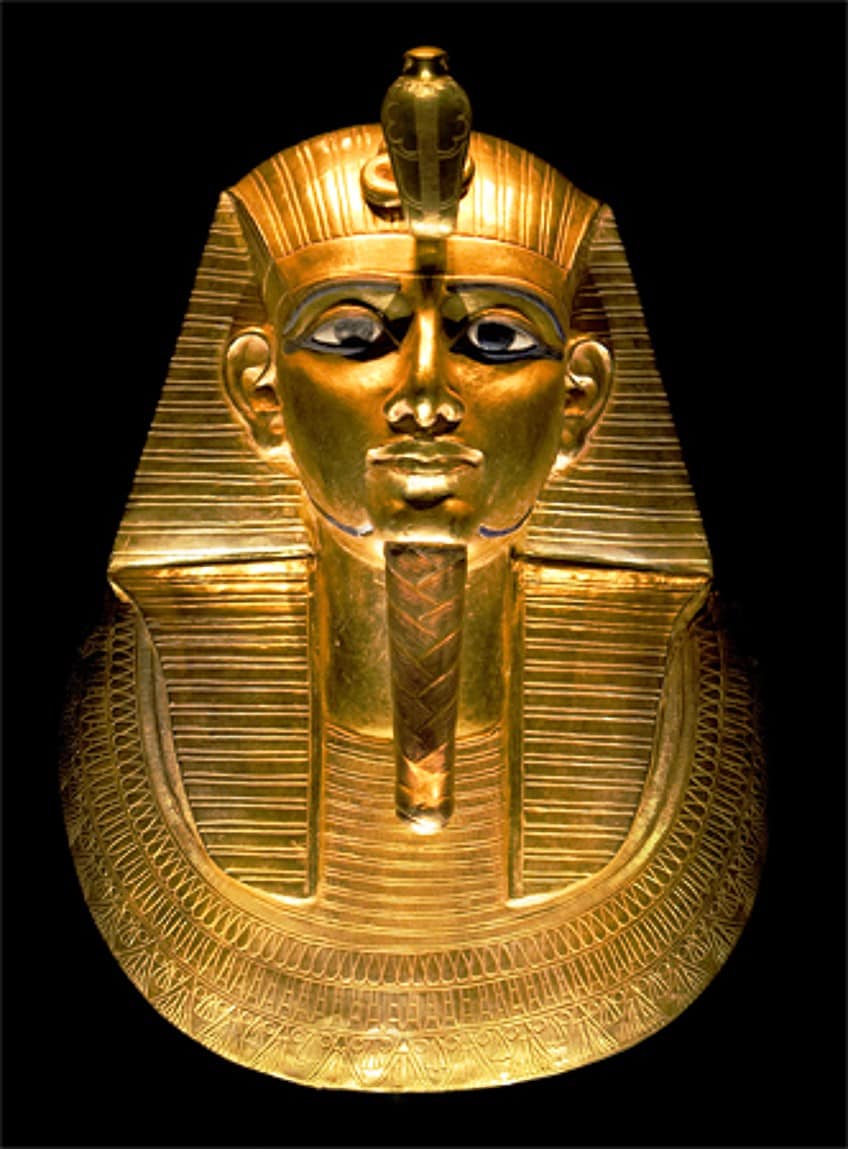

Mask of Tutankhamun (c. 1323 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 1323 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 1323 BCE |

| Medium | Gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian, obsidian, turquoise, and glass paste |

| Site Found | Tomb KV62, Valley of the Kings, Egypt |

| Current Location | The Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

Mask of Tutankhamun (1323 BCE); Roland Unger, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mask of Tutankhamun (1323 BCE); Roland Unger, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This is one of the finest artifacts from ancient Egypt and it was closest to the king’s mummified remains. It’s both iconic and loaded with meaning. It was a revered artifact with a purpose: to assure the king’s resurrection. Egypt’s funeral art served a function other than commemorating deceased loved ones.

Art played a part in their religion, in the philosophy that promoted royalty, and in cementing society’s hierarchy.

In this mask, we see a young man’s face. In truth, he was hardly more than a boy. Tutankhamun, sometimes known as “The Boy King,” was about 19 years old when he died.

His skin is flawless and nearly heart-shaped. He has a delicate, tapering jawline, wide almond-shaped eyes, round cheeks, and high cheekbones. His lips are large and sensual, but not too intense. They’re virtually bow-shaped, with a pucker like that of a baby. The deep indentations at the ends of his lips appear to give him a calm expression, nearly but not entirely smiling.

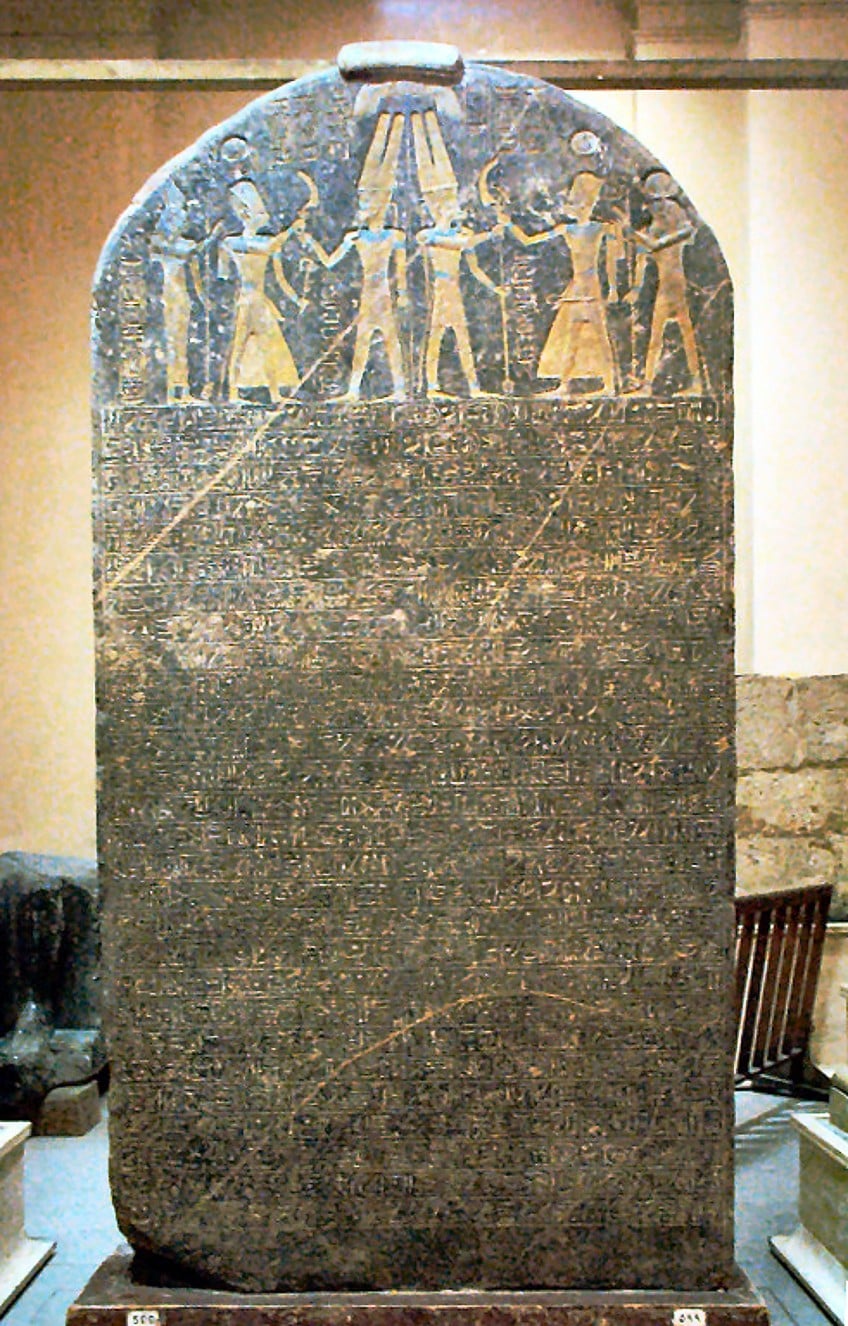

Merneptah Stele (c. 1208 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 1208 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 1028 BCE |

| Medium | Granite |

| Site Found | Merneptah’s funerary chapel, Thebes, Egypt |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

Merneptah Stele (c. 1208 BCE); Webscribe, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Merneptah Stele (c. 1208 BCE); Webscribe, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Merneptah Stele is an inscription written by Merneptah, an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who ruled approximately 1213 BCE. The text is mostly about Merneptah’s triumph over the ancient Libyans and their collaborators, but the final three lines of the 28-line poem are about a military campaign in Canaan, which was then part of Egypt’s imperial conquests. It is also known as the “Israel Stele” since Biblical archaeologists translated a group of hieroglyphs as “Israel.” Other translations have been proposed, but the exact meaning of the text remains in dispute.

The stele is widely regarded in the Biblical research community as the first written mention of Israel outside of the Bible, and the only such example from ancient Egypt.

The four reliefs depict the conquest of three cities, one of which is identified as Ashkelon; Yurco speculated that the other two are Gezer and Yanoam. The fourth depicts combat in open hilly land against a Canaanite enemy. While the concept that Merneptah’s Israelites may be seen on the temple walls has influenced numerous hypotheses about the meaning of the text, not all Egyptologists agree with Yurco’s attribution of the reliefs to Merneptah.

Mask of Psusennes I (c. 1000 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 1000 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 1000 BCE |

| Medium | Gold and lapis lazuli |

| Site Found | The tomb of Pharaoh Psusennes, Egypt |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

Mask of Psusennes I (c. 1000 BCE); The original uploader was Nrbelex at English Wikipedia., CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Mask of Psusennes I (c. 1000 BCE); The original uploader was Nrbelex at English Wikipedia., CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Professor Pierre Montent, a French Egyptologist, found Pseusennes I’s tomb near Tanis in 1940. Unfortunately, most of the wooden artifacts had decomposed owing to the wetness of the earth in Lower Egypt. The mask, however, which is composed of gold and lapis lazuli, was unearthed.

The mask is regarded as “one of the finest of Tanis’ treasures.” Psusennes I appears with the royal headpiece topped with the royal cobra, on this golden mask.

He is adorned with a gorgeous plaited fake beard. The mask is comprised of two pieces of beaten gold that are soldered together and held together by five visible nails from the rear. The monarch wears the royal Nemes headdress, often composed of linen, and is crowned by the royal cobra. This shielded the monarch from opponents and adversaries both while living and after death. The pharaoh wears a heavenly-plaited fake beard as a sign of majesty. He also wears a wide Usekh collar with flowery carved embellishments.

The Mask of Wendjebauendjed (c. 1000 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 1000 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 1000 BCE |

| Medium | Gold |

| Site Found | The royal necropolis of Tanis (NRT III), Egypt |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

The Mask of Wendjebauendjed (c. 1000 BCE); Jon Bodsworth, Copyrighted free use, via Wikimedia Commons

The Mask of Wendjebauendjed (c. 1000 BCE); Jon Bodsworth, Copyrighted free use, via Wikimedia Commons

This mask depicts General Wendjebauendjed as a young man with a tranquil countenance softened by a sweet grin. The mask hid the wearer’s neck, face, and ears. It stopped at the mummy’s forehead, where six small-perforated hooks allowed it to be attached to the mummy’s head. The inlaid eyeballs are composed of various colored glass pastes. The nose is well-shaped, and the lips are small and plump. The ears are asymmetrical, with the left protruding farther than the right.

During the reign of Psusennes I, Wendjebauendjed was an ancient Egyptian commander and high priest. He is well known for his undamaged tomb, which was discovered by Pierre Montet inside Tanis’ royal necropolis.

Numerous jewelry items, including rings, pectorals, bracelets, and gold statuettes, were discovered within the tomb, together with a statuette of Amun made of lapis lazuli and the mask that covered Wendjebauendjed’s face. A large number of Wendjebauendjed’s four canopic jars were also discovered outside the tomb.

The Grave Mask of King Amenemope (c. 990 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 990 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 990 BCE |

| Medium | Gold |

| Site Found | The Royal Necropolis of Tanis, Egypt |

| Current Location | The Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

The Grave Mask of King Amenemope (c. 990 BCE); tutincommon (John Campana), CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Grave Mask of King Amenemope (c. 990 BCE); tutincommon (John Campana), CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The golden Grave Mask of King Amenemope, unearthed in the royal necropolis by Pierre Montet in 1939, was the first complete Egyptian Pharaoh’s tomb ever uncovered. This grave mask was part of Amenemope’s mummy-shaped gilded wood coffin. It is made of thick gold sheets fashioned with the king’s features. The royal cobra, which is mounted to the king’s forehead, crowns his round-shaped face. The sinuous, long body of the cobra falls from the headpiece and coils around itself before lifting its head.

The mask is constructed of pure gold with blue turquoise and red stone inlays. Bronze is used for the pupils, eye, and brow outlines.

Amenemope was initially interred in the single chamber of a modest tomb in Tanis’ royal necropolis; a few years later, during Siamun’s dynasty, the Grave Mask of King Amenemope was transferred and reburied within the chamber previously belonging to his presumed mother Mutnedjmet. When the excavators explored the little burial room, they originally thought it was built for Queen Mutnedjmet. Amenemope is best known for an influential text attributed to him titled The Instructions of Amenemope.

Statue of Khufu (c. 600 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 600 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 600 BCE |

| Medium | Ivory |

| Site Found | Kom el-Sultan, Abydos, Egypt. |

| Current Location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

Statue of Khufu (c. 600 BCE); Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of Khufu (c. 600 BCE); Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Although there are other statue pieces, this little sitting figure is the only known three-dimensional portrayal of Khufu that exists completely intact. Most Egyptologists believe the statue is contemporaneous with Khufu and most likely dates from his reign. However, because of its odd provenance, its date has been called into question on several occasions. Egyptologist Zahi Hawass denies that the sculpture is from the Old Kingdom. His claim that the figurine is from the 26th Dynasty has gained little attention and has not yet been challenged.

The statuette’s ritual function is likewise unknown. If it existed during the time of Khufu, it was either a typical statue cult or a funeral cult.

The king sits on an unadorned throne with a low backrest. He carries a flail over his shoulder with his right hand placed over his chest, the flail laying over his upper arm. The left arm is bent, and the lower arm is resting against his left leg. The palm of his left hand is lying on his left knee. His feet, like the pedestal, have broken away. Both the ridges at the rear and the ornamental spiral at the front of the red crown have fallen off. His head is significantly out of proportion to his body, with huge, protruding ears.

Dendera Zodiac (c. 50 BCE)

| Artist | Egyptian craftsmen (c. 50 BCE) |

| Date Completed | c. 50 BCE |

| Medium | Sandstone |

| Site Found | Temple ceiling, Dendera, Egypt |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum, Paris |

Dendera Zodiac (c. 50 BCE); Louvre Museum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Dendera Zodiac (c. 50 BCE); Louvre Museum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This sandstone bas-relief illustrates the constellations in pictorial style. In approximately 5 BCE, during the Greco-Roman Period, it was installed on the ceiling inside the Hathor Temple in Upper Egypt. It was removed from the temple and transported to France by an antique dealer in the early 19th century after being found during Napoleon’s campaign to Egypt. It is one of the oldest representations of the viewable stars that have been preserved.

Even though it includes many of the modern Zodiac symbols, it is more appropriately referred to as a star map.

It depicts both a lunar and solar eclipse as well as all five planets known to the ancient Egyptians in an arrangement that only happens once every thousand years. Many historians believe that the death of Ptolemy Auletes in 51 BCE and the subsequent ascent to power of his daughter the following year, are related directly to its creation. However, the precise use or purpose of this unusual depiction of celestial bodies is unknown.

That concludes our look at famous artifacts from Egypt. Egypt is among the most established and rich civilizations on the planet, and ancient Egypt artifacts have withstood the test of time. Ancient Egyptian architecture and art are unmistakable, from the sky-scraping pyramids to the fascinating sphinx that serves as a gatekeeper to the pharaohs’ graves. Yet, it is the smaller famous Egyptian artifacts that provide insight into the people behind the monuments.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Oldest Egyptian Artifact Ever Discovered?

The first Egyptian artifacts were not created by the ancient Egyptians, or at least not by the people associated with mummies, pyramids, and hieroglyphs. These amber-colored stones may appear simple, but they are hand axes created by our human predecessors roughly half a million years ago. These are amongst the most significant museum artifacts, not because they are shiny or gilded, but because they give insight into hominid behavior in pre-historic Egypt.

Which Museum Has the Most Egyptian Artifacts?

The place to go where you will find the largest collection of ancient Egyptian relics in the world is the Egyptian Museum. Situated in Cairo in Egypt, the Egyptian Museum is estimated to house more than 120,000 artifacts from ancient Egypt.

What Can We Learn From Ancient Egyptian Artifacts in the Modern Day?

Ancient Egypt artifacts have revealed important details about the life of the ancient Egyptians. They believed in a life after death and buried the deceased with items that they would need to survive in the afterlife. As a consequence, the tombs of the ancient Egyptians include a plethora of items that shed light on their unique and advanced society and lifestyle.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.