Greek Goddess Selene – Ancient Personification of the Moon

The moon has been humanity’s constant companion for millennia as a source of light, timekeeping, and inspiration to countless peoples. The Greek world held the moon personified in the form of the beautiful Greek goddess Selene, the chariot-rider of the night sky. As a patron of love and vigilant guard of order, find out about her many interesting connections below!

What to Know About the Goddess of the Moon

| Name | Selene, or Mene |

| Gender | Female |

| God of | The moon personified |

| Personality | Benevolent, dedicated, and zealous |

| Symbols | The moon, lunar disk or crescent, bull horns, bulls, nimbus, billowing cloak, and the torch |

| Consorts | Endymion, Zeus, and Pan |

| Children | Fifty daughters and Narcissus by Endymion, Pandia and Ersa by Zeus, the four Horae by Helios, and the mortal Musaeus of Athens |

| Parents | Hyperion and Theia |

Selene was upheld to be the moon incarnate to the ancient Greeks, riding over the world after her brother the sun-god and beaming down silver light.

She was an illuminating and watchful presence in the Grecian myth, helping to explain and maintain the order of the world while holding elements of time-keeping and seasonal connections.

Selene was identified with many other ‘moon’ goddesses and was mostly worshiped in connection to them, such as Artemis and Hekate with whom she is closely associated. Her romanticized central mythos also upheld her as a figure sympathetic to plights of the heart and a paragon of eternal love and passionate longing.

Relief depicting Selene in her chariot on a Roman sarcophagus (3rd Century CE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Relief depicting Selene in her chariot on a Roman sarcophagus (3rd Century CE); Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Selene’s Background and Family

The ancient Greeks knew the sun and moon as a brother and sister pair, who rode their shining chariots across the sky and through the underworld, lighting up the world as day and night. The Olympian pair of Apollo and Artemis may be more familiar to you, but their roles as chariot riders are actually much older. Before the rise of the Olympians, these domains naturally belonged to the Titans, who preceded them as ruling gods.

The Sun was known as the tireless Helios, and the moon was his sister, the Titan Selene.

The Greek goddess Selene, as well as Helios and Eos, are the only gods besides Zeus to have certain Proto-Indo-European origins. Her name in Greek originates from selas (σέλας), a noun meaning “light” or “brightness” or “gleam”. She was also called by the name Mene, with the dual meaning of moon and lunar month, which seems to have older origins through the Proto-Helenic word for month (*méns). The word itself may have been derived from the Proto-Indo-European word *mḗh₁n̥s meaning “moon” or “lunar month”, from the root word *meh₁- or .”to measure”.

Roman Intaglio depicting Helios in his chariot and Selene with a star in the sky; Naples National Archaeological Museum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman Intaglio depicting Helios in his chariot and Selene with a star in the sky; Naples National Archaeological Museum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

It seems that the Proto-Indo-European version has the genders of the sun and moon swapped, and the male moon god went by the reconstructed name of *Meh₁not. Not only does this name share the same root word as “Mene” but like Selene he too was a god of lesser importance in mythology.

Selene herself has no dedicated temple. It is argued she was always in view anyway; however, she was worshiped in conjunction with other deities like her siblings and at certain temples as Luna, the Roman counterpart of Selene.

Family

The Greek goddess Selene is named by Hesiod’s Theogony (C8th or C7th BCE), the Homeric Hymn 31 to Helius (C7th – 4th BCE.), and other writings, to be a daughter to the Titan Hyperion and his sister Theia. This pair belongs to the original twelve or thirteen Titan children of Gaia and Uranus and is her most common parentage. Through these two Selene is also made sister to Helios, the sun, and Eos, the dawn. Other later sources say her father is Pallas, son of Megamedes, or have her as being the daughter of Helios.

Selene is named mother to the Menai, the fifty goddesses of the lunar months in the Greek Olympiad, who were fathered by her mortal lover Endymion.

The poet Nonnus also ascribed Narcissus to be a son of the famous pair. She is considered the mother of Ersa, the personification of Dew, and Pandia by Zeus. It has been suggested that Pandia was at first an aspect or epithet of Selene, as the festival Pandia that is dedicated to Zeus is celebrated on a full moon. She is also considered the mother of the Horae by Helios and the great priest poet Musaeus of Athens was reputedly her son by Eumolpus.

Roman relief depicting the dance of the Horae (c. 320 CE); Cavaceppi (c. 1700’s), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman relief depicting the dance of the Horae (c. 320 CE); Cavaceppi (c. 1700’s), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Significance of Selene in Greek Mythology

Selene is a second-generation Titaness and a moon goddess. There are many gods associated with the moon but if you ask an ancient Greek what Selene is the goddess of, they will tell you that she alone is the moon as its divine incarnation. She is part of the natural order, explaining its make-up and the rules that govern the ancient Greek world. The moon and its predictable cycles have long been used for keeping track of time and the duration of the seasons.

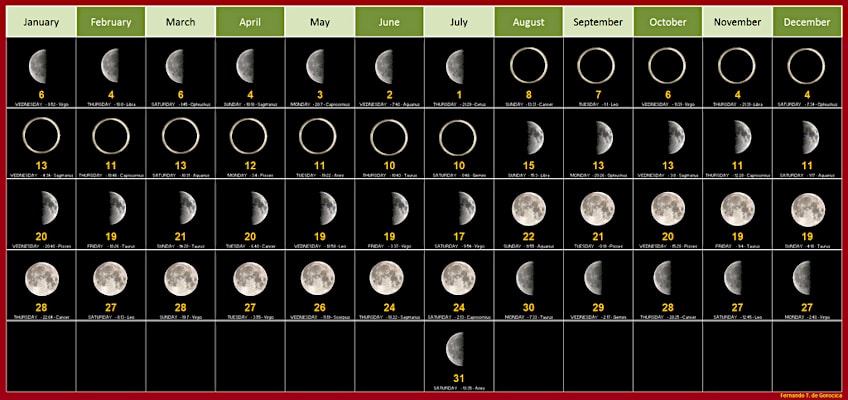

Lunar Calendar for 2021; Fernando de Gorocica, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Lunar Calendar for 2021; Fernando de Gorocica, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Selene is said to denote the lucky work on specific days and warn farmers of the weather to come. Alongside measuring months, she also controls the duration of nights and the lighting of the world during them, something Zeus himself takes advantage of in myth.

Selene is the ruler of months and mother of the 50 goddesses known as the Menai, who themselves rule the 50 lunar months in the four-year Olympiad cycle.

As lady of the moon, she brings cool and restful nights to the world and is believed to nourish the earth. She is believed the origin of dew, personified in her daughter Ersa, which rejuvenates nature. She is often noted as a ‘nurse’ of all, and a Homeric hymn addresses her as the one who gives “to nature’s works their destined end”. Selene is also connected to childbirth, which is measured in months and held as being easiest during the full moon.

Lovelorn Lady Moon

The association of the moon and love is an old one, and our Titaness Selene is no different. Her central myth details her intense and desperate desire for the beautiful mortal Endymion who is put to sleep so she may look upon him forever.

Her love is her most frequent reference in its capacity for good and ill and is used as a metaphor in many literary works.

She held a real influence as a figure of love, possibly in combination with her ties to Hekate, as she was believed to be invoked in love spells. Her eternal love became a defining trait of hers in both mythologies and how the Greeks perceived and invoked her.

The Attributes and Personality of Selene

Selene is a fascinating figure because her sterner attributes upholding order and being watchful of strife are juxtaposed by her portrayal as a quintessential figure of beauty and the eternal joys and desperate longings of love. Like the moon has a bright and dark side, so too does Selene show warmth and benevolence alongside sorrow and severity.

Appearance and Personality

The main descriptors of the Greek goddess Selene come from the Homeric Hymns where she is uniquely described as long-winged.

The crescent or lunar disk usually depicted upon her brow has matched the common naming of her as a “horned” and ‘brightly crowned’ goddess.

Homeric Hymns to both her and her brother describe her as “bright-tressed” while other sources include “lovely-tressed” and “white-armed” along with other high praise of her feminine beauty. Most often she is noted as a figure bright and shining, either through her gleaming silver rays or her pale countenance. She is also described as “dark-”, “bright-” and “cow-eyed” along with having white cheeks.

Roman altar with a depiction of Selene accompanied by either the Dioscuri or Phospherus and Hesperios (the morning and evening stars) (2nd Century CE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman altar with a depiction of Selene accompanied by either the Dioscuri or Phospherus and Hesperios (the morning and evening stars) (2nd Century CE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Her personality is described as “mild” and “benevolent”, and in writings, she often takes pity upon those who remind her of her love for Endymion. The Orphic Hymns flesh out the role of this mysterious moon goddess more, attributing her bullhorns and adding a flaming torch with which she is often depicted after the Hellenistic period.

She is a ruler of the night and granted titles like “all-seeing” and “all-wise” while she is said to be of vigilant character and notably against strife, having been named as being one who rejoices in peace and admires horses.

Another trait associated with her through her myths is her depth of love, as seen in her central myth with Endymion and Attica associating her with Aphrodite. She is shown as a passionate deity, in both her amorous relations with Zeus and her love and longing for Endymion. Her passions can sometimes be to a reckless degree as some myths have her abandoning her cosmic course to be with the latter. The dark side to her capacity for passionate love is the depth of her pain, as she is driven to desperation in longing and is named “love-wounded moon” and called upon by the lovelorn and betrayed.

Selene and Endymion by Ubaldo Gandolfi (c. 1770); Ubaldo Gandolfi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Selene and Endymion by Ubaldo Gandolfi (c. 1770); Ubaldo Gandolfi, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Selene is a deeply empathetic figure, however, her status as a goddess worthy of the highest respect is apparent and her aptitude for challenge is clear. Her divine pride leads her in swift and efficient retribution towards Ampelus upon his ‘challenge’ of her, while her might is evidenced in both her domain powers and martial prowess. Her weighty role as an active agent of order can be seen in her purported vigilance over the world and her preference for peace. She is noted as a key fighter in the battle with the Giants known as the Gigantomachy.

Eclipses known as kathaireseis or “casting downs” were believed the work of witches pulling down the “all-seeing” and “all-wise” “eye of the night” so they could perform their spells undisturbed. The practice was thought to bring ill-fortune and there was a Greek proverb for self-inflicted pains that went that you were “bringing down the Moon on yourself”.

On the whole, she is viewed as benevolent, evidenced by the prevalence of prayers to her in practice and in literary and theatrical works, though whether this was particular to women or not is a mystery. In her Endymion myth, some versions say she never abandons her duty, simply looking forward to seeing her eternally sleeping lover each night, and in combination with her dutiful vigilance and steadfast actions against the giants, she portrays a zealous personality in the depth of her decisive drive and the reliability and unfaltering nature of the moon in its motions.

Symbols Attributed to Selene

The moon itself is a symbol of Selene, as while many other goddesses are associated with it, she alone is its personification. In a similar vein, she is crowned with a lunar disk or crescent moon, commonly placed on her head or brow but may be placed on her shoulders. The crescent is often placed in mimicry of horns, and she is associated with having bullhorns in particular. Her steeds are usually horses, cows, or oxen.

Attic red-figure cup with an image on the interior of Selene in her chariot drawn by winged horse (c. 490 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure cup with an image on the interior of Selene in her chariot drawn by winged horse (c. 490 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As the shining moon, she is depicted as having a nimbus, which is a surrounding halo of shining rays or a disk of light. Another of her descriptions is that she is noted to have an arcing veil or cloak about her person or head, and this has become a staple of her representations in works of art and a clear distinction from goddesses like Artemis. She also came to be associated with holding a torch after the Hellenistic period, an item which may be hers due to the dual symbolism of the literal lighting of the darkness of the night and the metaphorical enlightenment of knowledge. Another who shares this symbol is Hekate with whom she is closely associated.

Detail from a Roman sarcophagus depicting Selene holding a torch and veil (3rd Century CE); Baths of Diocletian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from a Roman sarcophagus depicting Selene holding a torch and veil (3rd Century CE); Baths of Diocletian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Selene’s Worship and Domain of Influence

The worship of Selene is an interesting topic as her personal cult was not as prominent as other gods in the pantheon, even in comparison to her brother Helios whom she was often honored alongside. The Greco-Roman culture was also famous for attempting to match their gods to foreign ones and held very disparate representations of deities across territories.

While Selene has very little direct worship, as the Greek goddess of the moon she had many possible associations and was often worshiped according to them.

Selene’s Places of Influence

Through Strabo, we know of a temple estate of Selene and the localized moon god known as Mēn. It was founded in Armenia during the 2nd century BCE and was supposedly an effort to fight the influence of a different moon goddess called Ma of Comana.

These sorts of localized deities being used as a form of diplomacy were common throughout the Greco-Roman world.

Another example was a pair of statues in a Laconian oracular sanctuary of Helios and Pasiphaë, the latter being used to refer to Selene in her capacity as Helios’ daughter, where she was said to send answers in dreams through an oracle.

Syrian-Roman cameo depicting Luna / Selene in her ox-drawn chariot; I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Syrian-Roman cameo depicting Luna / Selene in her ox-drawn chariot; I, Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

We also know of two stone images, one of a sun with beaming rays and the other the horned crescent moon, in Elis which was believed to be the kingdom of Endymion in his kinglier mythos. Selene also had an altar in Epidaurus, Argolis; but it is argued that she was mainly worshiped outside temples, as the “all-seeing, eye of night” that was the moon could be observed directly from anywhere in the world at any time. Her possible importance in rural farmlands through her connections with seasons and agriculture could support this view.

Her Roman counterpart Luna was listed by Varro as one of the 20 principal gods of Rome and had two temples in the city, one on the Aventine Hill and another one reported as shining on the Palatine Hill.

Worship Practices Surrounding Selene

While little of how Selene herself was honored is known, we do know she was worshiped on the new and full moon. Monday is dedicated to her, the word itself meaning “day of the moon”. Her importance as a keeper of time and cosmic order is common among moon goddesses, and she may have had connections to the famous Orphic Mysteries. The few instances we have of people invoking her seem to portray her role as a figure of protection and enlightenment. Sources say she could bestow safe passage through the night and give sleep.

Allegory of the Night (Luna / Selene) by Jan can den Hoecke (c. 1650); Jan van den Hoecke, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Allegory of the Night (Luna / Selene) by Jan can den Hoecke (c. 1650); Jan van den Hoecke, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As the watcher of the night, she may also have had a connection to dreams and visions as the roman counterpart of Selene, Luna, was also reported to have. It was also believed that women could pray to Selene for help during love spells and childbirth. These may have been a part, or the cause, of her associations with childbirth goddesses like Hera (Juno) and Eileithyia which may have ‘Selene’ as an epithet. Depictions of her coming down to Endymion became popular on Roman sarcophagi in the 2nd century BCE as a symbol of eternal love, longing, and reunion. Around the 5th century CE Nonnus also writes identifying her with Bacchus as a goddess of lunacy.

We know from records that there was a kind of flat cake made in the shape of the moon called ‘selene’ used as an offering to her. Another cake was decorated in the style of horns which could represent the full moon or ox, both symbols of Selene, by the name of boûs meaning “ox”. The boûs was recorded as being used as an offering to Selene as well as other gods such as Hecate, Artemis, and Apollo, though whether it was a case of their association to Selene or hers to them is unclear.

Selene as the moon has become associated with many gods over time. She was honored and had altars with her siblings and other celestial gods, such as in Pergamon at the sanctuary of Demeter. It seems she was primarily worshiped through association with more important deities. Most prominent in her worship was her entwinement with that of Artemis the goddess of the hunt and Hecate the goddess of witchcraft, which she later formed a functional triad with. She is notably invoked with Hekate in reference to magical forces and Artemis as a moon goddess.

Votive altar dedicated to Luna / Selene (turn of the 2nd/3rd Century CE); Landesmuseum Württemberg, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Votive altar dedicated to Luna / Selene (turn of the 2nd/3rd Century CE); Landesmuseum Württemberg, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

As the ages progressed, Selene and her brother Helios as the moon and sun-drivers became amalgamated with Artemis and Apollo, and both were sometimes referred to as Phoebe and Phoebus respectively. She has also obtained the name “Cynthia” in reference to being from Mount Cynthia, known as one of the origins of Artemis.

Selene: One of the Three-in-One

The triad of Artemis/Selene/Hekate was established largely by Roman writers and was not as prevalent as one might think. The triad came to be conflated with the popular themes of the ‘primordial triple-headed goddess’ of modern neopaganism. The Horea, the three seasons, and the Morae, the three fates, were connected by Orpheus as being phases of Selene. This connection with time and seasons and fates, reinforced associations with the phases of fertility and womanhood, as well as the triple goddess as representing the journey of ‘birth’, ‘growth’, and ‘death’.

Phrygian grave marker depicting a Triple Hekate flanked by fertility goddesses below two stars and the moon (3rd Century CE); Calvet Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Phrygian grave marker depicting a Triple Hekate flanked by fertility goddesses below two stars and the moon (3rd Century CE); Calvet Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Artemis was considered the huntress of the Earth, Selene was the moon in the sky, and Hekate brought with her connections to the sea and underworld where the moon dives at the end of the night.

Modern neopaganism like Wiccan has popularized this view and it has made its way into various media representations, art, and popular thought alongside her popularity as a beautiful moon goddess and symbol of eternal and doomed love.

Selene in Mythology

The goddess’ central myth surrounding her eternal love of Endymion has gained many different iterations and messages. In some versions, Endymion was the king of Elis who won the boon of choosing his end in unageing sleep from Zeus before she ever saw him, in others he was a simple but beautiful shepherd who caught her eye. In all, Selene falls for him and longs to see him every night. In some versions it is her sorrow at his looming mortality that led her to place him asleep eternally, in others she pleads with Zeus to make him immortal, and he places the enchanted sleep upon him.

Fresco from Pompeii depicting Selene and Endymion (1st Century CE); Sash, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco from Pompeii depicting Selene and Endymion (1st Century CE); Sash, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The story always ends with Selene visiting and lovingly gazing at her lover asleep in his cave at Mount Latmos, with whom she bore the Menae and became a symbol of eternal and deep love.

Selene was also said to be seduced by Pan using a sheepskin, but it has been argued that Pan may have been an allegory for the shepherd Endymion.

Selene in the Gigantomachy

The defeat and imprisonment of her Titan children in Tartarus enraged Gaia. She spurred her other children, the aggressive and powerful Giants, to challenge the Olympians for rule over the cosmos.

Fragments of the Great Altar of Pergamon depicting Selene astride an ox participating in the Gigantomachy (2nd Century BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Fragments of the Great Altar of Pergamon depicting Selene astride an ox participating in the Gigantomachy (2nd Century BCE); Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A decisive part of one version of the myths holds that Gaia sought a herb that would have made the Giants undefeatable. Selene suppressed her light, as did her siblings Helios and Eos, to hide the herb from Gaia while Zeus raced to find them first and took them for himself.

According to Nonnus, Selene is also said to have fought Typhon directly, locking her lunar crescent ‘horns’ to his, and the engagement left scars upon the smooth surface of the lunar disk which explains why the moon is so marred.

The Pergamon Altar, famously depicting the Gigantomachy, has her riding side-saddle into battle accompanying her mother Theia alongside her siblings, showing her role in this victory of order over chaos was not trivial.

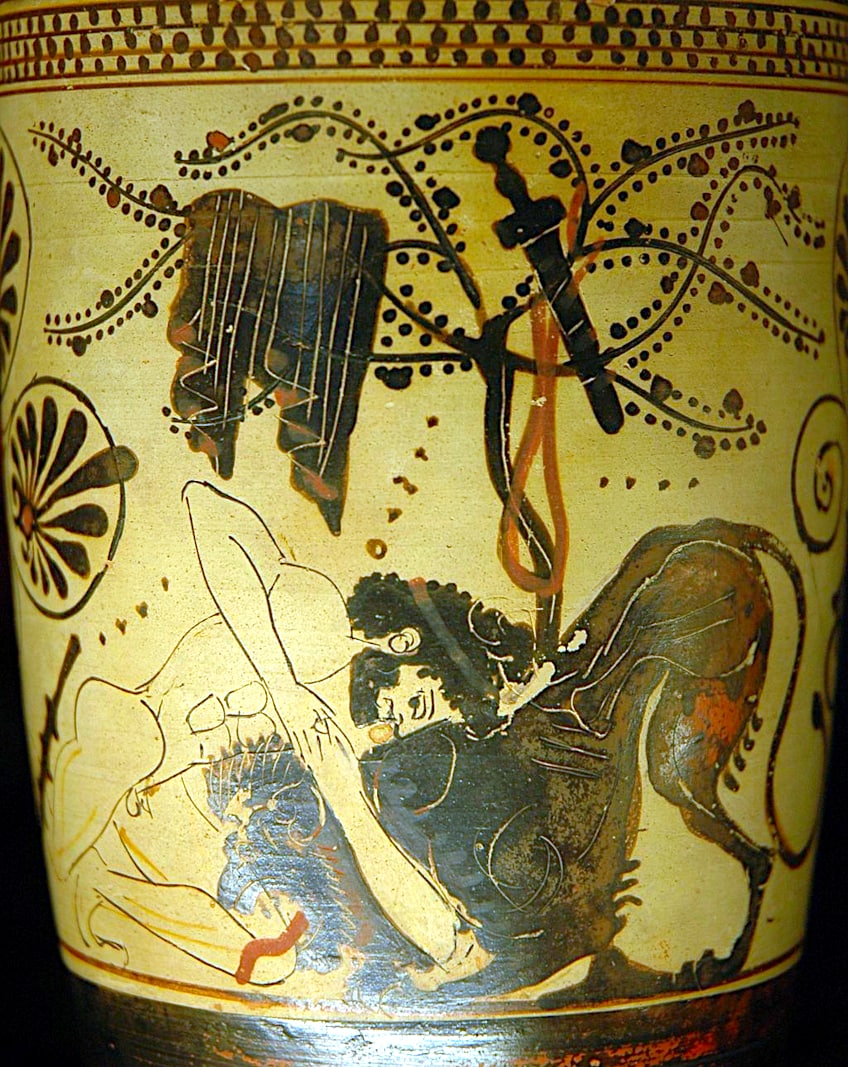

The Arrogance of Ampelus

It was well known not to challenge the Greek gods, for even without their very real influence in every aspect of human life, they were characterized as very temperamental by nature. Ampelos was a satyr, one of the wild companions of Dionysus.

One day he rode an ox and likened himself to the horned Selene who also rode one across the sky.

In a show of her divine wrath, the goddess sent a gadfly to bother his steed, which promptly threw and gorged Ampelus to death.

Attic red-figure plate with a depiction of a satyr (520-500 BCE); BnF Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure plate with a depiction of a satyr (520-500 BCE); BnF Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Connections to Heracles

Selene was also connected to the mythos of Heracles in two ways. Heracles’ parents are Zeus and Alcmena, however in order to conceive the hero, Zeus took on the form of her husband Amphitryon.

Zeus stretched one night to the duration of three by ordering Helios not to rise, and Selene to linger in the sky for the duration.

Later, the first of Hercules’ 12 Labors set by his cousin King Eurystheus was to slay the Nemean Lion. Later Roman sources (1st – 2nd century ACE) say that the monster fell from the moon, having been born or simply reared by Selene (Luna), possibly at the behest of Hera (Juno). Her role is mostly a small contextual one but frames the origins of arguably the most important hero in Greek mythology, setting the stage for the much-worshiped figure and the lessons he upheld in ancient Greek society.

White-ground lekythos with a depiction of Heracles killing the Nemean Lion (c. 500-475 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

White-ground lekythos with a depiction of Heracles killing the Nemean Lion (c. 500-475 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Lessons of the Greek Goddess Selene

Aside from explaining what is Selene the goddess of, the stories of Selene are deeply emphatic ones, that the Greeks identified with and respected in their emotive works. They are ostensibly about love, the power of the gods, and how the ancient Greek world came to be, but we can also find other themes in the tales of Selene, like the power of our passions and the promise of hope.

Through Endymion, we see the power of love and how deep emotions can influence us for good or ill, if we let them.

Having a deep passion, as Selene did for Endymion, shows how they can light up your life and drive you onward like nothing else can. The immortal Titaness who goes toe-to-toe with Giants, mover of the very cosmos, is helpless before the power of emotion and the joy it brings her. But like the moon, the only constant is their presence, as emotions can be ever-changing.

Two Men Contemplating the Moon by Caspar David Friedrich (c. 1825-30); Caspar David Friedrich, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Two Men Contemplating the Moon by Caspar David Friedrich (c. 1825-30); Caspar David Friedrich, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Endymion was mortal, and it was her fervid love for him that also brought her such deep sorrow and tunnel vision. In some myths she abandons her cosmic course to be with him and in most it is her wish to have him made immortal that condemns him to eternal sleep, whether she intended to or not. If looking at the version where she only asked for his immortality and Zeus placed him in eternal sleep as an obstacle, one can also be warned to be careful what you wish for, and that haste and obsession can make curses of the best of intentions.

These are the dangers of our passions, but the myths also give us something else alongside it, hope.

Selene is the moon that watches over the world, vigilant and benevolent. In the darkest of nights, she pities the wretched and wronged and offers light that you might find your way. She guides the months and seasons and may even guide you in dreams and visions. In the face of her love’s mortality, they found a solution. In the face of betrayal and strife, Selene stands firm and helpful. In the face of the scorching day, the moon revitalizes the world in the coolness of dew and the calmness of night. The moon may fluctuate in form or seem faint during the day, but it is always there. And in a similar vein, just as everything has an end it also has a new beginning just beyond it.

In Peril by John Atkinson Grimshaw (1879); John Atkinson Grimshaw, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In Peril by John Atkinson Grimshaw (1879); John Atkinson Grimshaw, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Be mindful of your emotions and situation, but do not hyper-focus on them. People live and grow at a constant rate, and there is always some way to change your fate and some faint hope for the future in the deepest despair. And whatever course you set in your personal or professional journey, devote yourself to it as fully and unfaltering as the goddess Selene.

Selene represents an ancient yet fundamental figure in Greek mythology, working to not only explain but maintain cosmic order. Her passionate portrayal and mysterious might have painted an attractive figure in practices and writings since ancient times. Her famous beauty and deep nature have inspired countless artworks and modern religious movements, captivating us just like the moon itself has done since time immemorable. Selene’s story touches our human spirit in all its duality. She displays unabashed empathy and zeal in life, comforting and calm diligence in her eternal duty, and that even in the darkest of nights, there is hope for light.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are Selene’s Symbols?

The Greek goddess Selene is the personification of the moon as the ancient Greeks understood it. She was said to drive her shining chariot or ride side-saddle on a horse or ox across the night sky. As such, her symbols are the crescent and lunar disk, often depicted as horns, as well as the chariot and ox. She is also depicted with a billowing cloak or veil about her and in the post-Hellenistic period, she gained the torch as one of her symbols.

What Is Selene the Goddess Of?

She was the moon personified and drove it across the sky every night. As the moon, she was a vigilant watcher of the world and ally of Zeus, as well as used for tracking time and seasons in the ancient world. She designated work to specific days and the lengths of the nights and months. She was also invoked in spells concerning love, as well as prayers for protection at night and concerns about childbirth.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.