Greek Goddess Hestia – Keeper of Warmth and Light

What is Hestia the god of in ancient Greek mythology, and what is Hestia’s Roman name? Hestia is the Greek goddess of the hearth, and her Roman name is Vesta. The Greek goddess Hestia is also connected to the home and other matters related to family life. Today, we shall explore Hestia’s facts related to her mythology, such as finding out the identity of Hestia’s parents and the role that she played in the ancient Greek myths.

The Greek Goddess Hestia Myths

| Name | Hestia |

| Gender | Female |

| Personality | Gentle and mild |

| Parents | Cronus and Rhea |

| Siblings | Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, Zeus, and Chiron |

| Domain | The family hearth |

| Spouse | None |

| Symbols | The hearth and fire |

Hestia’s parents are the Titans Rhea and Cronus. Hestia was one of the famous siblings that their father, Cronus, devoured. He had feared that one of his children would one day dethrone him from his position as the ruler of the gods. One of his children, Zeus, was replaced with a stone before he was swallowed and thus escaped the same fate as his fellow siblings. He then managed to make his father to vomit up all of his brothers and sister, the Greek goddess Hestia included.

As Cronus had feared, his children eventually dethroned him and took their place as the Olympian gods and goddesses.

Background and Family

Despite her rank, Hestia faded from significance in Greek mythology after the foundation of the new order, with very few appearances in Greek myths. Hestia, like Artemis and Athena, chose not to marry and decided to stay an immortal virgin goddess, tending to Olympus’ hearth. Considering her limited mythology, Hestia was still regarded as a powerful deity in ancient Greek civilization.

As the goddess of the sacrificial fire, the Greek goddess Hestia was expected to be presented with the very first offering at every home sacrifice.

The prytaneum’s hearth served as her formal sanctuary in the public sphere. A flame from her public hearth in the mother city was conveyed to the new community whenever a new colony was created.

Remains of the Prytaneum at Butrint in modern-day Albania (3rd Century BCE); Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Remains of the Prytaneum at Butrint in modern-day Albania (3rd Century BCE); Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

She is ranked among the first generation of Olympian gods. She was Zeus and Rhea’s eldest daughter, and sister to the other Olympians such as Zeus, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon. She was the first to be devoured by her father, Cronus, and the last to be regurgitated back out after Zeus made Cronus drink a special drink. Zeus tasked Hestia with feeding and maintaining the Olympian hearth flames using the fatty, flammable portions of animal sacrifices to the deities.

Hestia had her portion of honor whenever food was prepared or a sacrifice was burned; she also had a place of honor in all the gods’ temples. She was the most familiar to mortals of all the deities.

The Role of the Goddess of the Hearth

Hestia’s worship was based on the hearth, both household and civic. The fireplace was necessary for keeping warm, preparing food, and completing sacrifice offerings to deities. The Greek goddess Hestia was given the very first and last offerings of wine during feasts. According to Pausanias, the Eleans first made sacrifices to Hestia and subsequently to other gods. According to Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, Cyrus the Great offered first to Hestia, then to the ruler Zeus, and last to any other deity proposed by the magi.

The hearth was regarded as central to the home and any neglect of this fireplace was seen as a symbolic failure to care for one’s family and home.

Likewise, if her public hearth was neglected it was seen as a breach of one’s duty to the community at large. While the fire of the hearth could potentially be put out deliberately for ritualistic reasons, upon being relit, there were various purification rituals that had to be performed alongside the relighting.

Hestia as goddess of the home and hearth; artist’s impression

Hestia as goddess of the home and hearth; artist’s impression

The senior lady of the home was normally in charge of Hestia’s domestic cult, however, this was not always the case. Hestia’s ceremonies were frequently led by civil authorities at the hearths of structures in public; Dionysius of Halicarnassus indicates that the prytaneum of a Greek state or town was dedicated to the Greek goddess Hestia, who was attended to by the most prominent officials in the state. Hestia was there during the meal’s preparation and cooking. However, the hearth was utilized for much more than just cooking. When a baby was born in ancient Greece, a birth ritual was held in which the newborn was brought around the family hearth.

New members of the family, such as slaves or brides, sat in front of the fire and were bathed in the Greek goddess Hestia’s blessings of figs and nuts.

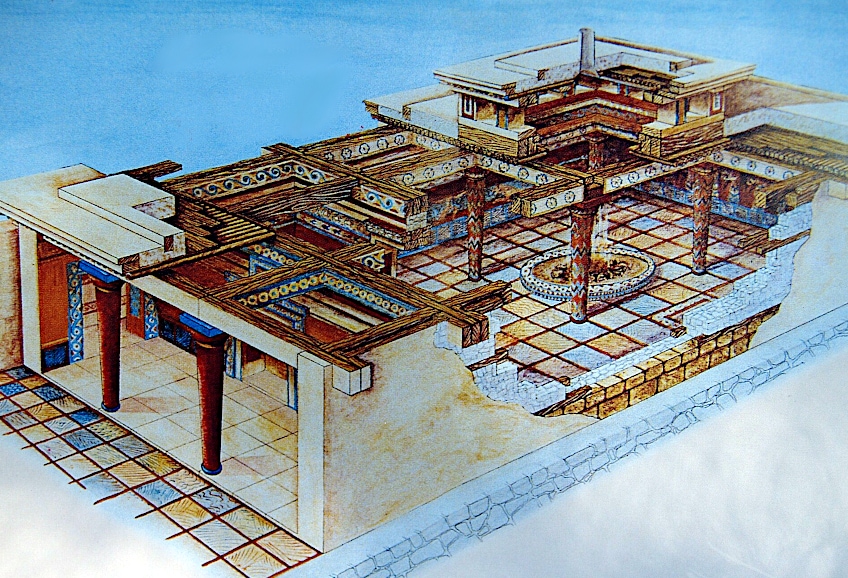

The flames would be quenched and then relit to represent the loss of a loved one if a family member passed away. The importance of the fireplace may be traced back to the Mycenaean era when the hearth was the center point of the dwelling. Palaces from the period had a central hall (megaron) with a throne room and a hearth; its existence in such a prominent location indicates that Hestia worship dates back to that time.

Reconstruction of a Mycenean palace with a hearth at the center of the great hall; Ken Russell Salvador, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Reconstruction of a Mycenean palace with a hearth at the center of the great hall; Ken Russell Salvador, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Consorts and Children

Apollo and Poseidon both fell in love with the Greek goddess Hestia and competed for her affection and hand in marriage. But the goddess of the hearth refused both of them, instead going to Zeus and swearing a huge oath that she would stay a virgin for all eternity and not ever marry. Aphrodite is characterized as having “absolutely no control” over Hestia in Homer’s Hymn to Aphrodite.

The link between Hestia, Poseidon, and Apollo, is also documented at the Temple of Delphi, where all three were worshiped together.

Poseidon and Hestia are also frequently seen together in Olympia. Because the three gods were so inextricably intertwined, the Greek goddess Hestia would have been aware of the rivalry between the two male divinities, which may have influenced her decision to stay unmarried. The Greek goddess Hestia knew that no matter who she selected, the dismissed god would cause havoc, so she sacrificed her longing for marriage in order to keep the Olympian gods at peace. Homer recalls Zeus’s reaction to his sister’s decision and the reverence he showed Hestia.

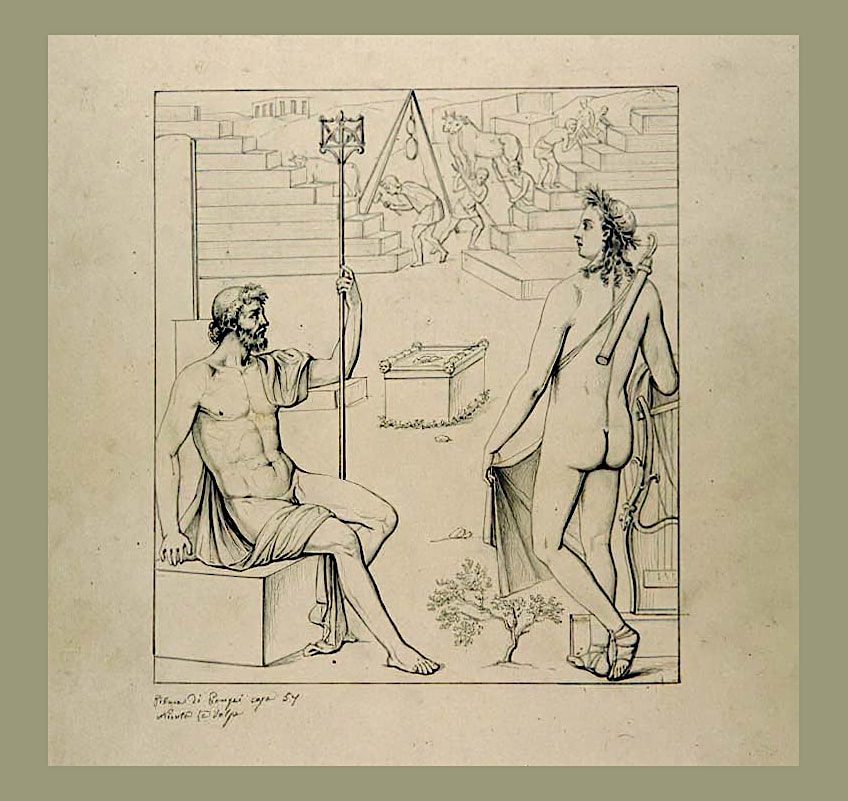

Poseidon and Apollo at the Walls of Troy by Nicola la Volpe after a fresco in the 1st Century BCE-CE House of Siricus Exedra (19th Century); Nicola La Volpe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Poseidon and Apollo at the Walls of Troy by Nicola la Volpe after a fresco in the 1st Century BCE-CE House of Siricus Exedra (19th Century); Nicola La Volpe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

“Zeus bestowed her with a high honor instead of a marriage and gave her the largest share of the household. She enjoys a place of prominence in all the gods’ temples, and she is the foremost of the goddesses among mortal men”. The phrase “the richest portion” implies that the most valuable and first part of any sacrifice will be offered to Hestia, followed by the other gods.

As a result, the Greek goddess Hestia was called before all other gods, and her altars could be found at all religious temples.

Hestia’s Status Among the Gods

During Plato’s time in Athens, there was a disagreement about whether Dionysus or Hestia should be included among the 12 major gods. The shrine to them at the agora, for instance, featured the Greek goddess Hestia, but the eastern frieze of the Parthenon featured Dionysus instead. However, the hearth remained immovable, and no account exists of Hestia ever being taken from her set residence. Burkert observes that because the hearth is immobile, The Greek goddess Hestia is unable to participate in the the Olympians’ various antics.

Relief depicting a procession of the 12 Olympian gods including Hestia (far left) instead of Dionysus (1st Century BCE/CE); Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Relief depicting a procession of the 12 Olympian gods including Hestia (far left) instead of Dionysus (1st Century BCE/CE); Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hestia is traditionally omitted from early images of the Gigantomachy since she is responsible for keeping the house fires blazing while the other gods are out. Nonetheless, a text on the north frieze of the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi indicates that the letter lines of one of the two divinities right next to Hephaestus could have been repaired as “Hestia,” though other potential candidates include Persephone and Demeter, or two of the three Fates.

Her mythographic role as Rhea and Cronus’ firstborn appears to explain the practice of making a modest gift to Hestia before any sacrifice, but this was not necessarily reflected in literature.

In the Odyssey, Eumaeus, Odysseus’ loyal swineherd, starts the meal for his master Odysseus by picking strands from the head of a boar and placing them into the hearth with an offering addressed to all the powers, then carves the carcass into seven equal portions, one of which he sets aside, raising a prayer to Maia’s son, Hermes, and the forest nymphs.

Hestia’s Roman Name

Vesta, the Roman counterpart of Hestia, performs comparable responsibilities as a heavenly personification of Rome’s “public,” household, and colonial hearths, uniting Romans in a type of extended family. Vesta is also associated with another story not found in the Greek tradition, which is told by Ovid, the Roman poet, in his poem Fasti, in which Vesta is nearly sexually assaulted by the god Priapus in her sleep, and only escapes this dreadful fate when a donkey shouts out, warning Vesta and leading the other gods to confront Priapus in defense of the goddess of the hearth.

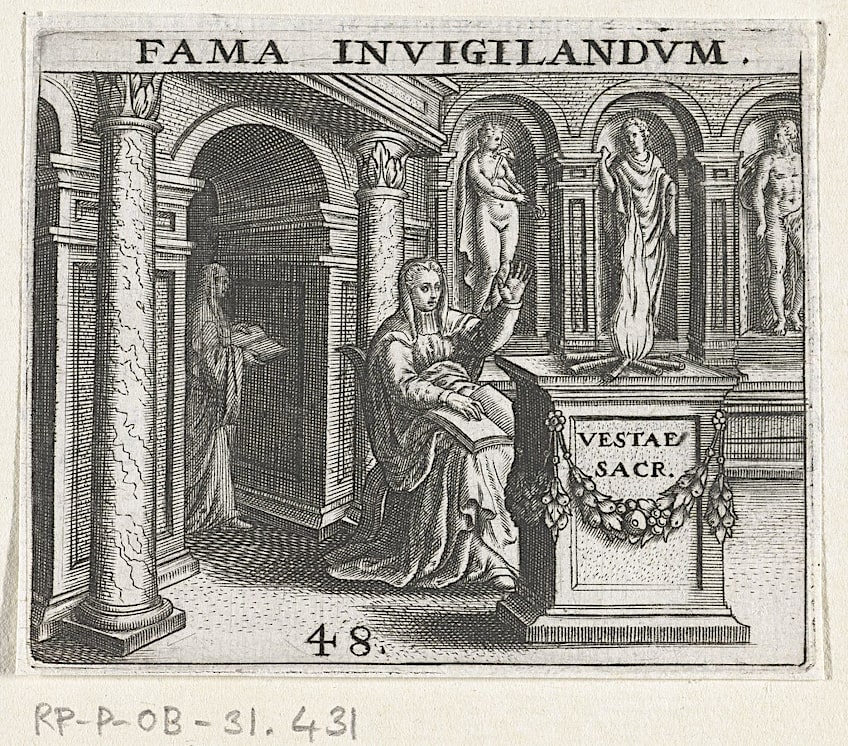

Vestal Virgin seated in front of the altar of Vesta by Theodor de Brynaar (1596); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Vestal Virgin seated in front of the altar of Vesta by Theodor de Brynaar (1596); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

This story is a near-word-for-word repetition of the myth of Lotis and Priapus, which was recounted earlier in the same book, with the exception that Lotis was forced to change into a lotus tree to escape Priapus, leading some scholars to speculate that the account in which Vesta replaces Lotis is merely there for the purpose of developing some cult drama.

In the Roman colosseum, the priestesses of Vesta known as the Vestal Virgins were the only women provided with special ringside seats. All other women, irrespective of status were required to sit with the slaves in the seats furthest removed from the arena.

Personality and Attributes of Hestia

Hestia is well-known for her cool and collected temperament. She is a domestic symbol, highlighting the value of family, community, and a peaceful living environment. Hestia is often portrayed as being modest and self-effacing, putting other people’s requirements and well-being first. Her personality features include a strong sense of hospitality and a strong desire to keep her house serene and welcoming. Because of her connection to the hearth fire, the Greek goddess Hestia also signifies the upholding of traditions and the holy rites performed in the home. The Greek goddess of the hearth is well-known for her passion, as well as her commitment to the sacred flame.

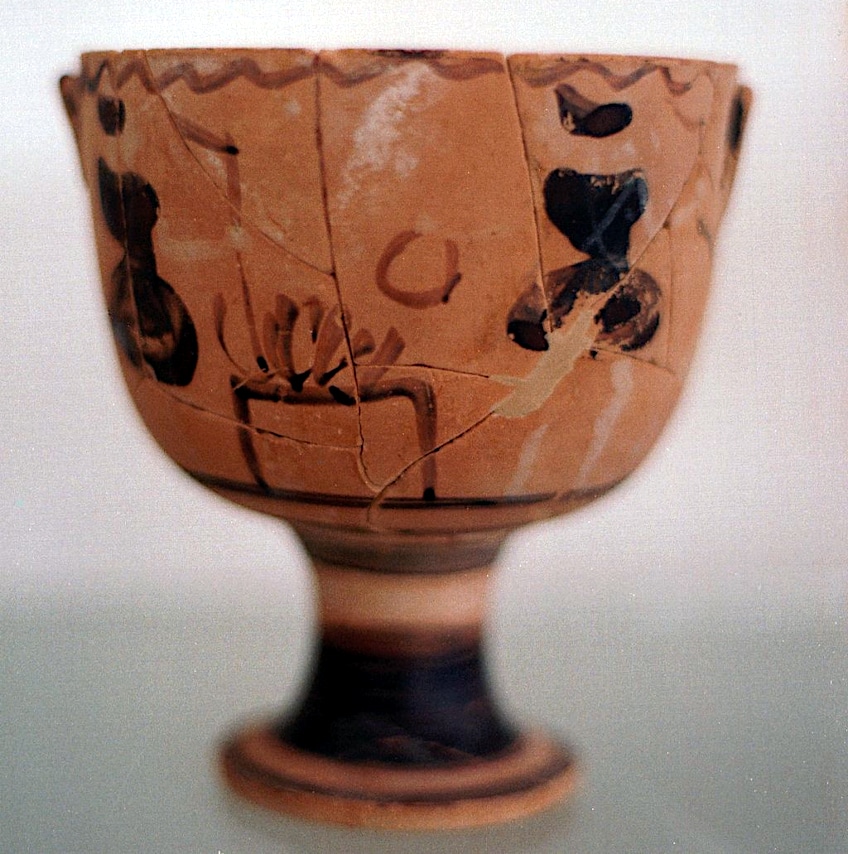

Small black-figure cup with a depiction of women around an altar on which a fire burns (c. 500 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Small black-figure cup with a depiction of women around an altar on which a fire burns (c. 500 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hestia’s Symbols

The Hearth is undoubtedly Hestia’s most important symbol. It is the focal point of the dwelling, where the sacred fire is kept blazing. The fireplace represents stability, warmth, and the coming together of one’s family and community.

Hestia’s holy fire is an important symbol for her.

It signifies the perpetual flame that remains on the hearth, representing the home’s enduring energy and vitality. The sacred fire of the Greek goddess Hestia is a sign of purification and her divine presence. Hestia is sometimes represented with a veil which symbolizes her humility and the sanctity of her function as a Greek virgin goddess.

Fresco from Pompeii depicting Hestia/Vesta (1st Century BCE-CE); Mario Enzo Migliori, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco from Pompeii depicting Hestia/Vesta (1st Century BCE-CE); Mario Enzo Migliori, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The veil also symbolizes her seclusion from the public domain and emphasis on the personal sphere. As a symbol of home and hearth, the kettle is often associated with the Greek goddess Hestia. It denotes dinner preparation, family caring, and the soothing warmth of the hearth fire. In some portrayals, she was accompanied by a donkey, which represents domesticity and the humble aspect of her vocation as the goddess of the hearth.

Hestia’s Physical Appearance

The Greek goddess Hestia is typically depicted as veiled, highlighting her humility and the sacredness of her function as a virgin goddess. Her face is obscured by the veil, indicating her retirement from the public domain and prioritization of domestic life. The Greek goddess Hestia is usually shown with a tranquil and calm look, which reflects her soft and loving personality.

Her manner conveys a sense of calm and inner serenity.

Hestia often appears wearing traditional Greek clothes, such as a flowing robe, emphasizing her connection to domesticity and tradition. As the goddess of the hearth, is sometimes represented carrying a flame or a torch, indicating the holy fire that she protects and keeps burning. This aspect symbolizes her attachment to the house as well as the warmth and stability of the fireplace.

Hestia’s Portrayal in Art

Because the Greek goddess Hestia did not have any specific mythology associated with her, she was not often featured in ancient Greek artworks.

When she was featured, it could prove difficult to distinguish her from many of the other Greek goddesses, particularly because she did not always possess any specific objects that were associated with her.

Hestia is typically depicted as a young woman with a head covering and modest dress, and she is occasionally distributing a libation, as in a red-figure kylix from c. 500 BCE currently housed in the Berlin Staatliche Museum, which depicts her alongside Hermes and Apollo as they take Hercules to Mount Olympus.

2nd Century BCE Roman copy of a c. 460 BCE Greek sculpture of Hestia; TimeTravelRome, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

2nd Century BCE Roman copy of a c. 460 BCE Greek sculpture of Hestia; TimeTravelRome, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Greek goddess of the hearth and the home appears on the renowned Francois Vase and, for the first time, on the northern frieze of Delphi’s Siphinian Treasury, where she and an unnamed goddess battle two giants in hoplite costume. Hestia could represent a seated figure in the group from the Parthenon’s eastern pediment, although the marble statue is severely damaged, making identification uncertain. Another probable figure is the so-called ‘Hestia Giustiniani’ – a standing female with a shrouded head and appropriately austere peplos attire – although this might equally be Demeter or Hera.

Hestia’s Shrines

Every public and private hearth was considered a sanctuary of the Greek goddess Hestia. Aeschines said that the Prytaneum’s fireplace served as the state’s “general hearth,” and that it included both an altar and an image of the Greek goddess Hestia in the Senate House. Ephesus had a temple devoted to Hestia Boulaea. Pausanias mentions a figurative statue of Hestia, as well as one of the deities Eirene, at the Athenian Prytaneum.

The Greek goddess Hestia promised protection from condemnation to those who respected her and would bring down anyone who insulted her.

According to Diodorus Siculus, “Theramenes sought refuge from the Greek goddess Hestia in the Council Chamber, jumping onto her hearth not for the sake of saving himself, rather in hopes that his slayers would prove their immorality by killing him there. There were very few free-standing temples devoted to Hestia. Pausanias describes one at Ermioni and another in Sparta, the latter of which has an altar but no image. Fighting is mentioned in Xenophon’s Hellenica within and around Olympia’s temple of Hestia, which is distinct from the city’s council chamber and surrounding theater: Andros has a temple dedicated to Hestia.

Inscribed fragment of an altar to Hestia Isthmia (5th-4th Century BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Inscribed fragment of an altar to Hestia Isthmia (5th-4th Century BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Prospective city-state and colonial founders sought permission and direction not only from their “mother city,” but also from Apollo, via one of his several oracles. At Delphi, he served as a consultant archegetes. He was the patron deity of colonies, constitutions, architecture, and city planning, among other things.

Other patron deities could be convinced to assist the new community, but there could be no polis without the Greek goddess Hestia, an agora, her holy hearth, and a prytaneum.

The Hestia Tapestry

The Hestia tapestry is a Byzantine-era pagan tapestry created in Egypt’s Diocese in the first part of the sixth century. It is presently housed at the Dumbarton Oaks Collection in Washington, DC, but is rarely seen. The Hestia tapestry is a late portrayal of the goddess Hestia woven of wool. It depicts the goddess seated on her throne, surrounded by two servants and six putti. The tapestry is known in Greek as “Hestia full of Blessings” and is typically shown with pomegranate fruit. Her headpiece and earrings are fashioned of pomegranates, and the favors Hestia bestows are also formed of the fruit.

Hestia’s Domains

Hestia is strongly connected to the virtue of hospitality. Offering hospitality and welcoming guests into one’s house was considered a holy obligation in Greek society. Hestia personifies hospitality, highlighting the value of charity, compassion, and making others feel welcome. The presence of Hestia gives peace and stability to the home.

Hestia emphasizes the preservation of traditions and social customs.

She symbolizes the significance of honoring and sustaining the beliefs and traditions passed down through generations. The power of Hestia extends to inner peace and tranquility. She exudes a calm and controlled temperament, urging others to find peace and harmony within themselves.

Hestia’s Myths

The Greek goddess Hestia, as an original Olympian goddess, was privy to several conspiracies to dethrone the King of the Gods, the mighty Zeus although they were always originating outside the circle. However, when Hera, Zeus’ wife, launched a revolution, the Olympians were compelled to choose sides. The Greek goddess Hera sought the help of Poseidon, Apollo, and Athena, but these gods all wanted the throne for themselves. Hera administered a drug to her husband, causing him to go into a profound slumber, after which the other gods bound the sleeping deity.

Jupiter (Zeus) seduced by Juno (Hera) by Crispijn van de Passe (1613); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Jupiter (Zeus) seduced by Juno (Hera) by Crispijn van de Passe (1613); Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

After Zeus was no longer a danger, the question of who would be the new monarch arose. Hestia, who was not interested in power, was the sole Olympian deity who did not take part in the coup. Hestia, on the other hand, opted to keep her distance because she lacked the strength to stand up to her bigger siblings. Zeus was eventually rescued by his supporters, the Hecatoncheires who assisted Zeus in regaining power and authority.

Zeus would inflict justice if he was deceived by those he trusted. While the other gods were punished, such as Poseidon, Hera, and Apollo, Hestia was spared.

Hestia and the Donkey

The gods and goddesses gathered to revel at Rhea’s big feast. There was eating and there was much delight, and the wine flowed freely, causing the entire group to become inebriated. The Greek goddess Hestia had elected to sleep outside after tending to her tasks. Priapus, a minor fertility deity searching for nymphs to have amorous with, was among the inebriated partygoers stumbling about attempting to sober up.

Roman fresco from Pompeii depicting Priapus (1st Century BCE-CE); Fer.filol, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman fresco from Pompeii depicting Priapus (1st Century BCE-CE); Fer.filol, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When he saw Hestia asleep, he carefully approached her, yet before he was actually able to do anything, Silenus appeared on the scene with his donkey. The donkey began to bray, waking up the slumbering goddess and alerting the gods. The Greek goddess Hestia then pushed Priapus away, while the other deities thrashed him for attempting to injure Hestia. The donkey who had awoken the Greek goddess Hestia was praised; on Hestia’s feast day, the Greeks decorated the donkeys and allowed them to relax all day.

That wraps up our look at Hestia’s facts. The Greek goddess Hestia was a goddess committed to her mission of keeping the Olympian hearth blazing in ancient Greek mythology. She guarded the Greek residence and kept the flames going inside. The Greek goddess of the hearth may not have been one of Greek mythology’s most well-known deities, yet her significance is unparalleled. After all, home is where the heart and hearth are, thus she had a particular place in the Greek people’s hearts.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Hestia’s Roman Name?

Hestia’s Roman equivalent is Vesta, the Roman goddess of the hearth and household. Vesta’s status was reinforced by her priestesses, the Vestal Virgins, who shared the same importance in the state and household. The Vestal Virgins’ major responsibility was to tend to the holy fire, which was placed in the temple of Vesta in the Roman forum. The Romans believed that if the sacred fire was ever extinguished, Rome would perish. Apart from the Roman goddess Vesta, Hestia was also affiliated with the Penates, according to Cicero. The Penates were thought to be the Roman deities of the household, and they were frequently connected with other house deities like Vesta.

What Is Hestia the Goddess Of?

In Greek mythology, Hestia is regarded as the goddess of the hearth. The family fireplace served as the household’s religious focus as well. Offerings and modest sacrifices were sent to the Greek goddess Hestia at the hearth by the people of the dwelling. The ladies carefully kept the fire in honor of Hestia, for the Greeks thought that if the fire went out, it would bring bad luck to the household. It was interpreted as a sign that the goddess had withdrawn her favor from the household. If the fire does go out, people can go to the communal hearth and relight their house fire. The fact that no temples were built in her honor is significant. However, in ancient Greece, a public hearth was frequently found in the prytaneum, which was a public structure. Hestia was symbolized by the sacrificial fire, at which prytanes or city leaders gave offerings to the Greek goddess of the hearth upon taking office.

What Were Hestia’s Symbols?

The most fundamental symbol for the Greek goddess Hestia is the family hearth. Along with this family fireplace, where the family would stay warm and make food, the sacred fire is also regarded as an important aspect of Hestia. Another of the goddess of the hearth’s important symbols is the veil or head covering. This was meant to symbolize her turning away from the public sphere in order to focus on the tasks involved in family life and in the family home.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.