Wives of Zeus – Why Did Zeus Have So Many Lovers?

Sometimes Greek mythology seems like an ancient type of soap opera, full of dramatic twists, turns, and conflicts between the characters. No soap opera would be complete without its fair share of sexual scandals and affairs, and the story of Zeus and his many wives and lovers is no exception. But while it is tempting to respond to ancient myths as though they were modern novels or reality shows, questions such as “who was Zeus married to?” and “did Zeus marry his sister?” have less to do with salacious entertainment than how Zeus structured his Olympian order, and the origins of the mythical heroes and heroines whose lives and deaths molded the ideas and values of ancient Greek society.

The Many Wives and Lovers of Zeus

Marriage in ancient Greek society was largely a monogamous affair, and in Greek literature and mythology, gods are presented as not only having one consort, but responding with jealousy when their husband or wife cheats on them with another. Such as Hephaestus exposing his wife Aphrodite’s adultery with Ares to the other gods.

By the same token, in Greek myth, Hera the goddess of marriage is unambiguously the wife of Zeus and Queen of Olympus, and there is no mention of the idea that the king of the gods had a harem filled with consorts and concubines.

Hera’s jealous rage whenever she discovers that Zeus has taken another lover is commonly presented as the justified response of a wife whose reasonable expectation of her husband’s fidelity has been broken. So where does the tradition of Zeus having not just a multitude of lovers, but at least seven wives fit in?

Silver Tetradrachm of Tenedos with a Janiform head of Zeus and Hera (c. 100-70 BCE); Exekias, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Silver Tetradrachm of Tenedos with a Janiform head of Zeus and Hera (c. 100-70 BCE); Exekias, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The first description of Zeus having seven wives occurs in the ancient poem ascribed to Hesiod that is known as the Theogony (the genealogy of the gods). The list of wives follows the moment where Zeus has become king of the immortals and he is dividing various honors and roles amongst the gods. The seven goddess are listed in the order Zeus married them, along with the divine children these unions produced.

In the context of the Theogony, these unions function less like conventional marriages and more like cosmic alliances, where Zeus fuses his powers with these divinities to produce a generation of new gods who represent essential aspects of the new Olympian order.

The notion of Zeus having multiple wives also reflects the ritual of hieros gamos (sacred marriage). In ancient fertility cults, the wedding of the god and goddess responsible for bringing good harvests were celebrated yearly, and was represented either as a union between the god and goddess, or with a priestess performing the role of the goddess copulating with the god, or a priest as the lover of the goddess. In antiquity, such regional cults and their mythologies gradually fused to produce the Greek myths known today, resulting in many characters that seem to share core traits.

Elsewhere in Greek myth and literature, it is stories of Zeus’ many lovers and the adventures of their children, often persecuted by a jealous Hera, that predominate.

In antiquity, kings commonly claimed descent from gods to justify their rule. As a result, legends of gods such as Zeus fathering children by mortal women abounded, with various city-states and regions celebrating their own local hero-cults. Add to that Zeus’ role as father of both gods and humans, as well as being the divinity associated with the fertilizing sky, and you have a recipe for endless love-affairs.

The Seven Wives of Zeus

The seven wives of Zeus tradition is first mentioned in lines 886-929 of Hesiod’s Theogony. Some of the main characteristics of Hesiod’s poetry include collective lists, the use of etymology (the meaning/origin of words and names), and a concern with the correct structure and order of things.

In keeping with these traits, the list of seven wives of Zeus represent a collection of goddesses ranging from abstract concepts to more familiar characters from myth, all of whom produce children who will characterize essential functions within Zeus’ new regime.

Metis

Zeus’ first wife was the Titaness Metis, daughter of Tethys and Oceanus. Her name means “wisdom, skill, or craft”. Described by Hesiod as “all-knowing”, Metis was the ideal choice of spouse for the third generation king of the gods whose reign would be the antithesis of the savage cycle of oppression and rebellion that characterized those of his forebears. However, there was a catch: Once Metis fell pregnant, Gaia and Ouranos warned Zeus that a son born to him and Metis would use his superior strength to overthrow him, just as Cronus and Zeus had rebelled against their fathers. To avert this disaster, Zeus tricked Metis and swallowed her, absorbing her power into himself.

Attic black-figure Exaleiptron with a depiction of the birth of Athena. Metis is shown underneath Zeus’ throne, symbolizing that she is now part of Zeus (c. 570-560); C Painter, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic black-figure Exaleiptron with a depiction of the birth of Athena. Metis is shown underneath Zeus’ throne, symbolizing that she is now part of Zeus (c. 570-560); C Painter, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hesiod does not tell how Athena was born, only that she was as wise as her father. But according to most versions of the myth, Zeus developed a terrible headache after swallowing Metis. It became so severe that he asked Hephaestus to relieve the pressure in his skull by cleaving it open with an axe. Hephaestus complied, and a young woman sprang fully armed from Zeus’ head.

This was the goddess Athena, daughter of Zeus and Metis. She would serve as mentor and protector of the greatest heroes in Greek myth.

Themis

Zeus’ second wife was the Titaness Themis whose name derives from tithemi which denotes something that is laid down as customary law or practice. She and Zeus had two sets of daughters. The first three were known collectively as the Seasons or Horae and they governed how humans should spent their time. Their names were Eunomia (good governance), Dike (justice), Eirene (flowering peace). The second set of daughters born to Themis and Zeus were known as the Fates or Moirai. Clotho spins the thread of an individual life, Lachesis weaves the thread into a person’s actions, while Atropos cuts it to bring that person’s life to its end.

Mosaic depicting the Thetis and Peleus giving the infant Achilles his first bath while the Moirai determine his fate (5th Century CE); Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mosaic depicting the Thetis and Peleus giving the infant Achilles his first bath while the Moirai determine his fate (5th Century CE); Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Eurynome

Zeus third wife was Eurynome “she of the broad (eurys) pastures (nomia)”. Eurynome was an Oceanide and according to Hesiod, exceptionally beautiful. Unsurprisingly, her daughters by Zeus were equally enticing. Known collectively as the Charites, Euphrosyne (good-hearted), Aglaea (splendor), and Thalia (to blossom) were charged with enhancing the enjoyment of life. While the daughters of Zeus and Themis governed how life was lived, the daughters of Zeus and Eurynome made that life worth living.

Roman fresco showing the Three Graces (1st Century CE); Bridgeman Art Library: Object 509706, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman fresco showing the Three Graces (1st Century CE); Bridgeman Art Library: Object 509706, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Demeter

Zeus’ fourth wife was Demeter. As the goddess of agriculture in Greek mythology, it has been suggested that her name derives from the combination of gê (earth) and mḗtēr (mother). Demeter was Zeus’ sister by their parents Rhea and Cronus. Hesiod’s description of their liaison is quite short. He states only that they had a daughter named Persephone whose abduction by Hades was approved by Zeus. This incident played a significant role in Greek myth and cult.

The consequences of Demeter’s loss of her daughter and the compromise that saw her partial return from the Underworld were celebrated in the Eleusinian Mysteries.

In Plato’s Republic he recounts the myth of El, which is widely believed to reflect the beliefs enshrined by the Mysteries: El dies in battle, but because his soul knows not to drink from the river Lethe (forgetfulness) he retains his memory, and when he is reincarnated, he tells the living of his experiences in Hades.

Marble relief showing Demeter and Persephone (500-475 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Marble relief showing Demeter and Persephone (500-475 BCE); Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mnemosyne

Zeus’ fifth wife was Mnemosyne whose name derives from mnēmē (a memory or remembrance). Elsewhere in the Theogony Hesiod recounts that Mnemosyne ruled the hills of Eleuther (a place far removed from other gods) where Zeus spent nine nights with her, resulting in nine daughters known collectively as the Muses.

Mnemosyne, Mother of the Muses by Frederic Leighton (1884); Frederic Leighton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mnemosyne, Mother of the Muses by Frederic Leighton (1884); Frederic Leighton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hesiod described the Muses making him a poet by handing him a staff and breathing a voice into him to signal his ability to speak on their behalf. Poets routinely requested first-hand information of distant events from these goddesses who were tasked with being present whenever anything occurred. As such, the Muses conferred reputational immortality, enabling humans to live long past their natural lives by committing deeds worthy of commemoration in art. Through choral singing and dancing, they fostered communal engagement in religious and social activities.

Hesiod also notes that the chief Muse Calliope gifted kings the ability to speak persuasively, enabling them to rule through reasoning rather than brute force.

Leto

Zeus’ sixth wife was Leto, daughter of Gaia and Uranus. Many ancient sources connected her name to lethe (forgetfulness) while modern etymologists find a connection with the Lycian word lada (wife).

Relief showing the hieros gamos (sacred wedding) of Zeus and Leto (2nd Century CE); Cobija, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Relief showing the hieros gamos (sacred wedding) of Zeus and Leto (2nd Century CE); Cobija, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Zeus and Leto’s children were Artemis and Apollo. Both were believed to bring death through sickness to humans with their arrows. While Artemis as “Mistress of the Beasts” presided over every wild and untamed thing, Apollo was the god most associated with music, the intellect, and civilized norms of behavior.

Hera

According to Hesiod’s list, Zeus’ seventh wife was Hera. This goddess was well-established long before Hesiod’s time, with her name appearing in Mycenean Linear B texts. Modern scholars cannot agree on the origins and meaning of “Hera”, but ancient folk etymologies linked her name with words meaning either “air” or “the lovely one”. Hesiod describes her as Zeus’ “lush and fertile wife”. Like Demeter, Hera was Zeus’ sister. Their children were Hebe, goddess of youth, Ares, the much-despised god of mindless violence, and Eileithyia, goddess of childbirth.

While Hera’s jealous rages spurred by Zeus’ various lovers are well known, Hesiod instead focuses on Hera’s jealousy towards Zeus for having given birth to Athena from his head. Hera responds by producing a child on her own, Hephaestus, the craftsman god whose skills are unmatched by anyone.

By ending his list of Zeus’ wives with a comparison of the births of Athena and Hephaestus, Hesiod uses one of his favorite poetic devices, known as ring-composition, where a narrative or a list ends with a reference to something mentioned at its beginning. The sequence in which Zeus marries his wives make many events from Greek mythology chronologically impossible. For example, both Hephaestus and Eileithyia are often present at Athena’s birth from Zeus’ head, yet in the context of this list, Athena is born first. Additionally, much of the mythology surrounding Leto is of her persecution by a jealous Hera, but here Leto not only precedes Hera, her children are born before Eileithyia, who also plays a prominent role in Apollo and Artemis’ birth story.

Roman fresco depicting the wedding of Zeus and Hera on mount Ida (c. 60-79 CE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Roman fresco depicting the wedding of Zeus and Hera on mount Ida (c. 60-79 CE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Maia, daughter of the Titan Atlas, who was mother by Zeus of the Olympian god Hermes, is not named along with these wives, but a few lines later where Hermes appears amongst other descendants of Zeus. Also, in Homer’s Iliad, the Titaness/Oceanid Dione was not only the mother of Aphrodite by Zeus, she even lived on Olympus. Is it because Hesiod has Aphrodite born from the severed genitals of Ouranos that Dione is not included on his list?

It is possible that the “seven wives of Zeus” was Hesiod’s literary invention, created to explore the role these specific goddesses and their children play in the broad structuring of the Olympian order. On the other hand, in mythology, inconsistencies such as those mentioned above are the norm.

The Lovers of Zeus

In antiquity, not only royal families, but entire peoples defined their identities in terms of ancestral links to the gods. The sons and daughters of gods and goddesses were the focus their own local hero-cults where rituals often involved having events from their lives and deaths commemorated in song. Such performances played a significant role in the development and transmission of the many ancient Greek myths we know of today.

As the king of the gods, Zeus was the ultimate divine ancestor, and the stories of how his children were conceived formed a major part of their myths.

In addition, most of these myths employ the figure of Zeus’ jealous wife Hera as an essential protagonist, whose efforts to either prevent their birth, or punish them for existing serves as proof of their status as special to Zeus. Below is a selection of some of Zeus’ most famous lovers and their children.

Semele

In Greek mythology, children born from the union of a god and a mortal typically do not inherit the divine parent’s immortality. That is why the story of Semele and her son Dionysus is so intriguing. Semele was the daughter of King Cadmus of Thebes. Zeus fell madly in love with her and secretly visited her when she was alone in her room every night. When Semele boasted of her divine lover to her sisters they mocked her and suggested that she was being deceived by an ordinary man pretending to be a god.

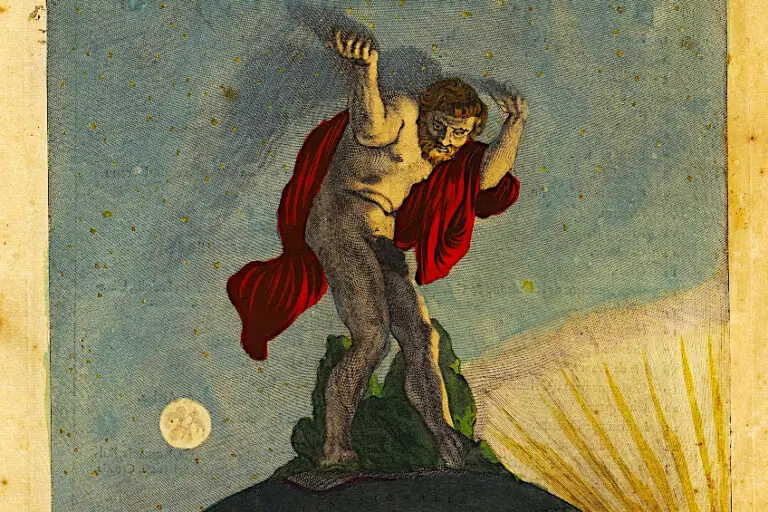

Jupiter and Semele by Gustave Moreau (between 1894 and 1895); Gustave Moreau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jupiter and Semele by Gustave Moreau (between 1894 and 1895); Gustave Moreau, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hera had discovered Zeus’ dalliance and disguised herself as Semele’s old nurse Beroe. She convinced the girl that since Zeus had promised to fulfill any request she made of him, she should ask him to appear before her in his full divine splendor. As Zeus was bound by his own promise, he had no choice but to comply.

Stripped of his protective disguise, Zeus in his true form as god of lighting instantly incinerated Semele.

At this moment Zeus spotted a fetus in his lover’s womb. He grabbed the child and placed it in his thigh to complete gestation. When the infant reached full-term, Dionysus was born from his father’s thigh. For this reason, Dionysus was described as “twice-born” and a fully-fledged god, since he was born from Zeus himself. Zeus’ sister Hestia even ceded her role as one of the great Olympians so that Dionysus could take her place in the Pantheon. Rumors spread among the Thebans, seeded by Hera, that Zeus was not Semele’s true lover. Many myths relating to Dionysus describe him proving his divinity to unbelievers.

With Zeus’ permission, Dionysus traveled to the Underworld and resurrected his mother Semele, so that, like Psyche, she could dwell among the gods alongside her child.

Danae

Danae was the daughter of Acrisius, king of Argos. The king had learnt from an oracle that his grandson would kill him, so to prevent this he locked his daughter in an impenetrable bronze tower. Zeus took notice and as the fortifications were not match for him, he visited Danae in the form of a golden shower. When Acrisius discovered that his daughter had given birth to a son she named Perseus, he locked them both in a chest and cast it out to sea.

Boeotian red-figure bell-krater with a depiction of Zeus visiting Danae in the form of a shower of gold (c. 450-425 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Boeotian red-figure bell-krater with a depiction of Zeus visiting Danae in the form of a shower of gold (c. 450-425 BCE); Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Perseus became one of Greece’s greatest heroes and famously beheaded the Gorgon Medusa with the help of Athena. Acrisius was ultimately killed by his grandson, but it was purely by accident. In antiquity, Perseus was considered the ancestor of the Myceneans, the Persians, and the greatest hero of all, Herakles.

Io

One of Zeus’ more intriguing lovers was a priestess of Hera named Io. She dreamt that she should become Zeus’ lover, but resisted. Her father consulted the oracles of Dodona and Delphi and both told him that Io should obey the dream. To hide his lover from his wife, Zeus transformed Io into an exceptionally white heifer. Hera was not fooled and instructed the giant Argus to keep watch over her. Hermes tricked Argus and decapitated him. Hera then sent a gadfly to torment Io who fled across the ancient world.

The route Io took has was the source of great debate for centuries. Along the way she met the chained Prometheus, the Amazons, Graeae, and the Gorgons.

The Ionian Gulf was named after her because she crossed it, as well as the Bosphorus (cow-crossing) Strait. Many plants across the Mediterranean region were believed to owe their origin to plants Zeus sent to sustain Io during her wanderings. She finally settled in Egypt where she supposedly either founded the cult of Isis, or was deified and worshiped as Isis. Io was also said to have invented the five vowels of the Greek alphabet.

Jupiter and Io from the Loves of Jupiter series by Antonio Allegri / Correggio (1520-1540); Kunsthistorisches Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Jupiter and Io from the Loves of Jupiter series by Antonio Allegri / Correggio (1520-1540); Kunsthistorisches Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Io and Zeus produced two sons, Epaphus and Iasus, and a daughter, Ceroessa. In some versions of her myth, Io was also the mother of Dionysus. Epaphus was believed to have founded the Egyptian town of Memphis, while Ceroessa married the sea deity Poseidon and had a son, Byzas, who founded the city of Byzantium, now known as Constantinople.

Europa

The myth of Europa encompassed multiple significant developments in the ancient Greek world.

Since antiquity, mythographers have connected Europa with the origins of the Minoan Civilization, Cretan bull-worshiping cults, the expansion of the Phoenician Empire, and even the invention of the Greek alphabet.

Zeus spotted Europa on the beach, either at Tyre or Sidon. He approached her in the shape of a dazzlingly white bull with horns like a crescent moon. When the bull lay down at Europa’s feet, she climbed onto it back, at which point Zeus leapt into the ocean and carried her to Crete where their five sons were born. Europa married Asterius, king of Crete and he adopted her sons as his own.

Terracotta figurine depicting Zeus disguised as a bull abducting Europa (400-300 BCE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Terracotta figurine depicting Zeus disguised as a bull abducting Europa (400-300 BCE); Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Minos became king of Crete, and the Minoan Civilization takes its name from him. Sarpedon became king of Lycia and was credited with the founding of Miletus. Rhadamanthus was famed for his wisdom and was believed to have created the “Cretan Code” on which the legal systems of Greek city-states were modeled. After death he was appointed a judge in the Underworld alongside Minos and Aeacus. Carneius was raised by Apollo and Leto, while the oracle at Dodona was named after Zeus and Europa’s son Dodon.

When Europa was kidnapped her father sent her brothers to retrieve her. Their travels resulted in the founding of various territories ranging from the city of Thebes to the island of Thasos, while the Phoenicians supposedly took their name from her brother Phoenix.

Alcmene

Alcmene’s encounter with Zeus marked the origin of many of the most compelling stories in ancient Greek myth. Renowned for her chastity, Alcmene refused to consummate her marriage to her new husband Amphitryon until he had avenged the murder of her brothers. When her husband came to her room and recounted the details of his expedition she rewarded him with three nights of love-making. However, the man she thought was her husband was actually Zeus disguised as Amphitryon. Her outraged husband tried to burn Alcmene alive, but Zeus put out the fire with a rainstorm. Aphitryon relented and remained married to Alcmene who gave birth to Herakles, son of Zeus and Iphicles, son of Amphitryon.

Paestan red-figure bell-krater with a depiction of Alcmene on the pyre saved by a rainstorm sent by Zeus (c. 340 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Paestan red-figure bell-krater with a depiction of Alcmene on the pyre saved by a rainstorm sent by Zeus (c. 340 BCE); ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Zeus was so excited about Herakles’ future greatness that he declared that the child born on the date of Herakles’ expected birth would be the next ruler in the dynasty of Perseus, Alcmene’s grandfather. When Hera heard this she instructed the goddess of childbirth to delay Alcmene’s delivery and induce the birth of another descendant of Perseus, Eurystheus. Zeus was bound by his oath, and Herakles could not claim the crown.

Hera would torment Herakles for the duration of his life. In fact the hero’s name itself reflects his complex relationship with the queen of the gods.

Herakles translates as Hera + kleos, the kleos (fame/renown) of Hera, which may sound odd, given Hera’s enmity towards Herakles. However, were it not for Hera constantly devising new challenges for him, the greatest hero of Greek mythology would not have achieved many of his most famous feats. In addition, when he died and was admitted to Olympus as a god, Hera gave him her daughter Hebe, goddess of youth in marriage.

Like Semele, Alcmene was also believed to have been granted immortality after death. In some accounts she married Europa’s wise son Rhadamanthus and lived with him in the Isles of the Blessed, in others she lived on Olympus.

Ganymede

While family structures in ancient Greece were based on the institution of heterosexual monogamy, homosexual relationships were not uncommon. In mythology the gods frequently took lovers of both sexes.

Zeus’ most famous male lover was a young shepherd from Troy named Ganymede.

He was said to be the most beautiful human alive, which meant that it was inevitable that he would catch the eye of Zeus. The king of the gods either sent an eagle to snatch Ganymede and carry him to Olympus, or Zeus took the form of an eagle to do so himself. Ganymede was granted immortality so that he could serve as cup-bearer to the gods. A role that had formerly belonged to Hebe until she married Herakles.

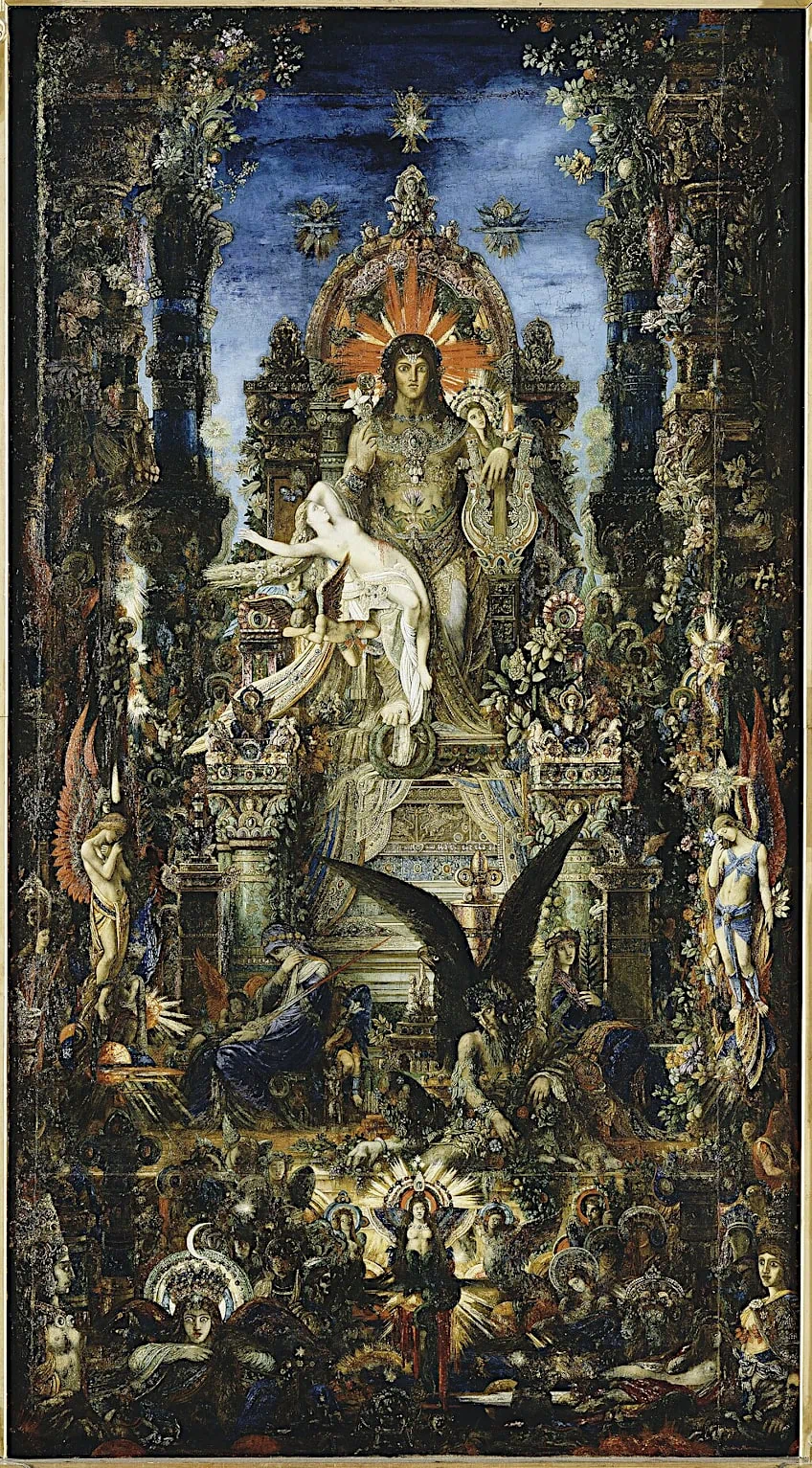

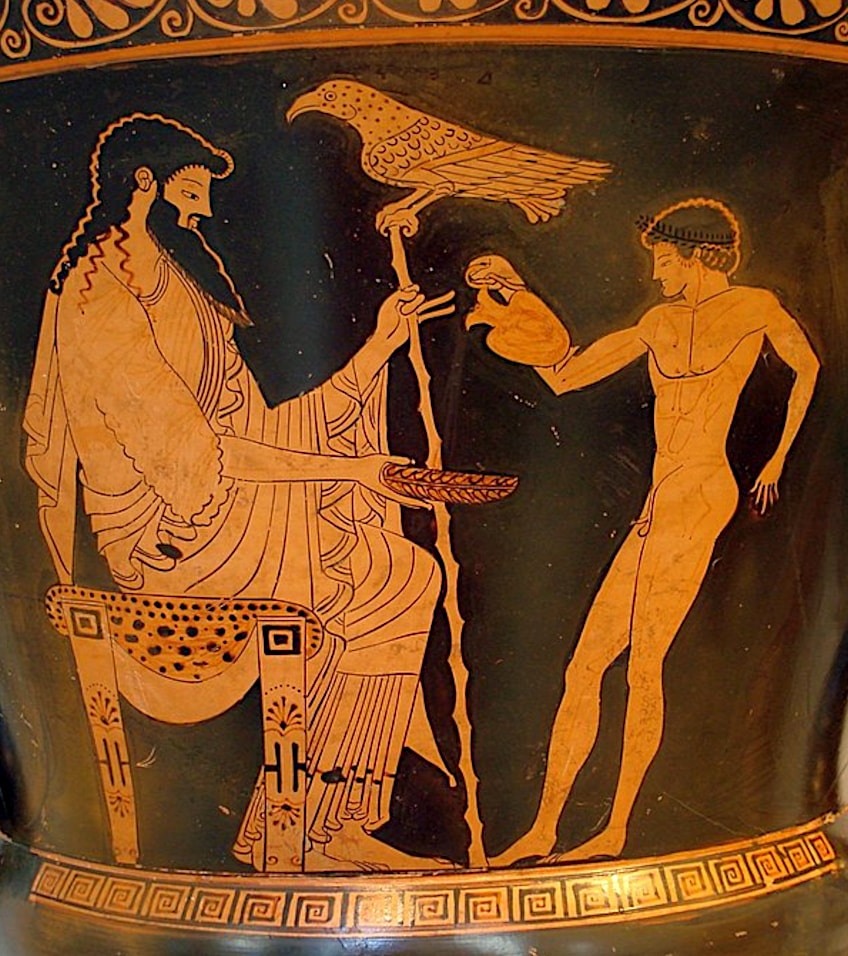

Attic red-figure calyx-crater with a depiction of Ganymede pouring Zeus a libation (490-480 BCE); David Liam Moran (= User:One dead president), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Attic red-figure calyx-crater with a depiction of Ganymede pouring Zeus a libation (490-480 BCE); David Liam Moran (= User:One dead president), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

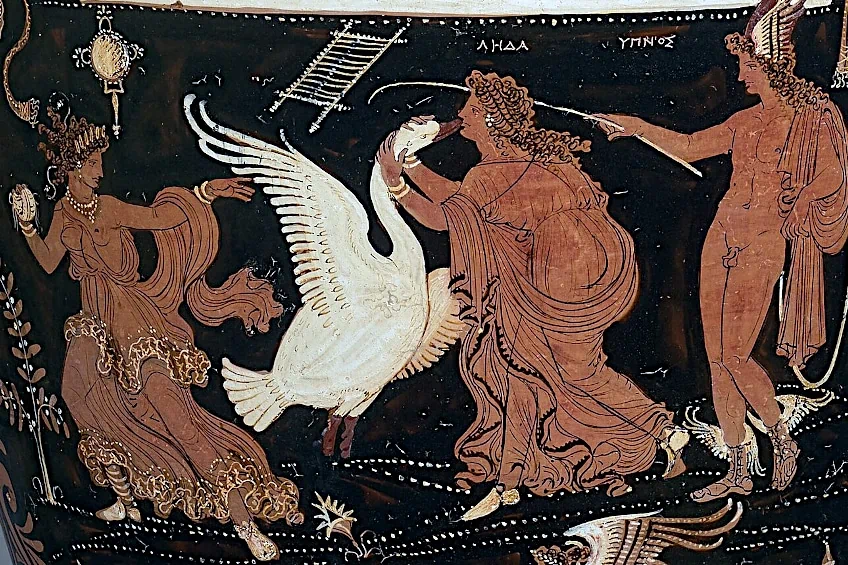

Leda

Leda was the daughter of King Thestios of Pleuron and wife of King Tyndareus of Sparta. Leda’s beauty caught the eye of Zeus. The god approached her in the form a swan while she was bathing. Zeus laid down close to Leda and then impregnated her. Later that same day Leda also became pregnant by her husband.

As Zeus had slept with her disguised as a swan, Leda’ pregnancy resulted in two eggs. Each egg produced a set of twins: Polydeukes and Helen were generally considered to be Zeus’ children, whereas Castor and Clytemnestra were Tyndareus’.

Castor and Polydeukes were known as the Dioscuri and were considered protectors of sailors and travelers. Their myth is believed to have derived from an ancient Indo-European cult of twin gods of horsemanship. When they died, Polydeukes as son of Zeus was offered immortality, but he declined to be immortal alone and asked to share it with his brother, so the Dioscuri alternate their time between the gods and the underworld.

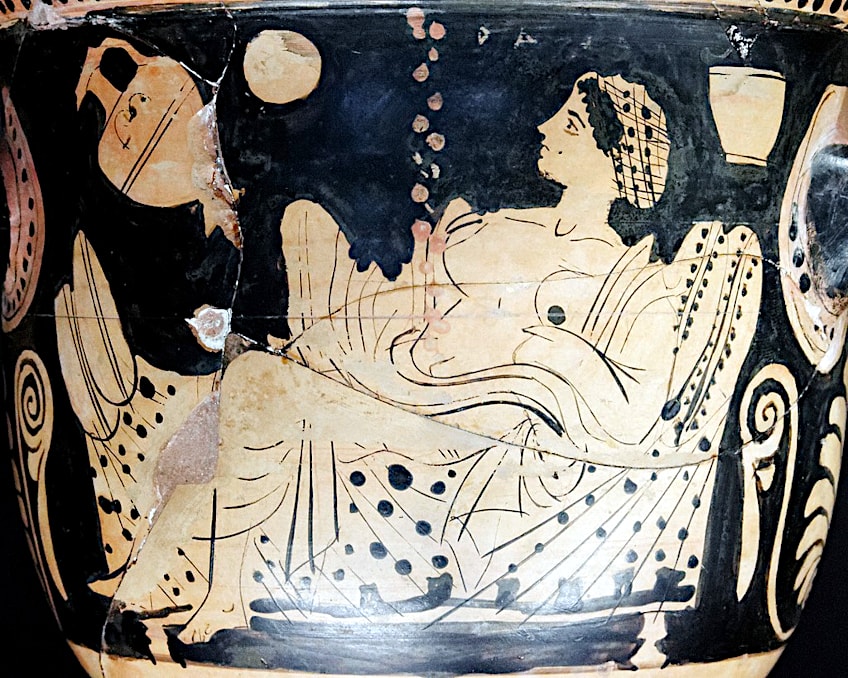

Detail from an Apulian Louthropos showing Leda with the swan (c. 330 BCE); Getty Museum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from an Apulian Louthropos showing Leda with the swan (c. 330 BCE); Getty Museum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Helen was considered the most beautiful woman in the world, and young men came from all over to court her. To avoid conflict, King Tyndareus asked each man to swear an oath to come to the aid of whichever man she chose for her husband. Helen married King Menelaus of Sparta and lived happily until the goddess Eris instigated a disagreement amongst the goddesses Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. Prince Paris of Troy was asked to decide which of the three goddesses was the most beautiful. Aphrodite won after promising Paris that she would help him to seduce Helen.

When Menelaus found that his wife had absconded with the Trojan prince, he asked every man who had sworn to come to his aid for assistance in getting her back. The result was the Trojan War.

Clytemnestra married King Agamemnon of Mycenae. She famously murdered him in his bath with the help of her lover after he returned home after the Trojan War. She did so in revenge for Agamemnon sacrificing their daughter Iphigeneia to secure favorable winds when he left to invade Troy. Clytemnestra was then murdered by her son Orestes, who was duty-bound to avenge his father’s death. Leda’s encounter with Zeus gave rise to stories that formed the basis of some of ancient Greece’s greatest myths and works of literature, including the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Oresteia, to mention but a few.

That wraps up our list of the wives and lovers of Zeus, the mighty king of the Olympian gods. Their number and strange narratives reflect the complexities of ancient Greek myth and cult. Sometimes they fell in love with him, other times they were simply fooled by his shapeshifting magic. However, thanks to all of these unions, we have a pantheon of gods, heroes, and heroines that that make Greek mythology and literature so compelling.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Many Wives Did Zeus Have?

The list of seven wives of Zeus is first provided by the ancient poet Hesiod in the Theogony. In this origin story Zeus allied himself with various goddesses while establishing his new Olympian order. They were Metis, Themis, Eurynome, Demeter, Mnemosyne, Leto, and finally Hera. In Greek mythology the goddess most often described as the wife of Zeus was his sister Hera, goddess of marriage. In addition to these seven consorts, there were many other goddesses and humans who were lovers of Zeus and mothers to his children.

Did Zeus Marry His Sister?

Yes, the king of the Olympian gods shared the same mother and father as the other Olympians. Hera, for example, was not only his principal wife but also his sister. Their father was the Titan Cronus and their mother was Rhea. He also had a daughter by another of his sisters, Demeter. Sibling-consorts are a common occurrence in mythology across the world. In the case of Zeus, the king and father of the gods is also a fertility god and the father of mortal heroes from whom many royal dynasties traced their origins.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.