Temple of Artemis at Ephesus – Sanctuary of the Ephesian Diana

The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus was a Greek temple devoted to the deity Artemis, also known as Diana of the Ephesians. But how was the Temple of Artemis built and how was the Temple of Artemis destroyed? Today, we will answer all those questions as we explore the history and facts about the Temple of Artemis.

An Exploration of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

| Architect | Chersiphron (c. 6th century BC) |

| Date Built | c. 550 BC |

| Function | Temple |

| Location | Selçuk, Turkey |

The Temple of Diana of the Ephesians was constructed in the sixth century BC on the west coast of modern-day Turkey. It was massive, twice the size of other temples in Greece, even the Parthenon. The huge Ionic temple was razed by an intentional fire in the fourth century BC and subsequently reconstructed. After being reconstructed numerous times, it was finally destroyed in 401 AD by a mob of Christians. Nowadays, just the foundations and a single column remain to inform us of the location of what was once the finest temple in the ancient Mediterranean world.

Who Was Artemis/Diana of the Ephesians?

Ephesus was a Greek settlement founded in the eighth century BC; however, Greek migrants had been present from before 1200 BC. The Ephesians revered the Greek goddess Artemis (or Diana of the Ephesians to the Romans), and her birthplace was said to be nearby Ortygia. Artemis represented forests, wild creatures, hunting, purity, childbirth, and prosperity. The goddess’ religion in Ephesus featured eastern characteristics adopted from deities like Cybele and Isis. Her portrayal in artworks, with surviving sculptures being adorned with symbolic eggs, alludes to her status as a goddess of fertility, unlike everywhere else in Greece. As a result, the goddess worshipped in Ephesus is frequently called Artemis Ephesia.

The Artemisian Cult

The ancient temeton under the subsequent temples certainly housed some type of “Great Goddess,” but nothing about her religion is known. The later founder-myths of Greek emigrants who established the worship and temple of Artemis Ephesia are referred to in literary records as “Amazonian.” The riches and magnificence of the temple and city were viewed as proof of Artemis Ephesia’s omnipotence, and served as the foundation for her local and worldwide reputation: despite the serial tragedies of Temple demolition, each restoration – a tribute and homage to the goddess – brought greater prosperity. Large crowds flocked to Ephesus in March and early May to observe the annual Artemis Procession.

Temples, shrines, and festivals dedicated to Artemis could be found across the Greek realm, but Ephesian Artemis was special. The Ephesians regarded her as their own and hated any foreign assertions to her protection. When Persia deposed and succeeded their Lydian ruler Croesus, the Ephesians downplayed his role in the temple’s reconstruction. Overall, the Persians treated Ephesus well, although they took several holy treasures from Artemis’ Temple to Sardis and introduced Persian clergy into her Ephesian worship, which was not forgotten. When Alexander defeated the Persians, his proposal to fund the temple’s second reconstruction was respectfully but firmly declined. Ephesian Artemis provided a tremendous religious edge to her city’s diplomacy.

Alexander the Great Mosaic. Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Alexander the Great Mosaic. Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Ephesian Artemisia festival was extensively emphasized as a vital component in the pan-Hellenic festival circuit throughout the Hellenic and later Roman administrations. It was an important part of the region’s cultural and political character, as well as a good chance for youthful, single Greeks to find marriage partners. Pliny recalls the goddess’ procession as a great crowd-puller, and it was immortalized in one of Apelles’ best artworks, which featured the goddess’s portrait paraded through the streets and accompanied by maidens. The festival games were named after and maybe sponsored by Emperor Commodus during the Roman Empire.

Bust of Emperor Commodus. Paul Getty Museum, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Bust of Emperor Commodus. Paul Getty Museum, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

According to the Greeks, the Ephesian Artemis is a unique version of their deity. In Greek mythology, Artemis is Apollo’s twin sister, a virgin deity of hunting, the wild, and the moon who, although being a deity of childbirth, was noted for her virginity.

At Ephesus, a goddess affiliated with Artemis was adored in a pre-Hellenic cult figure made of wood and ornamented with jewels. The traits are most reminiscent of Egyptian and Near Eastern deities, and least reminiscent of Greek goddesses.

The goddess’ legs and body are contained inside a tapered pillar-like shaft, from which her feet emerge. The deity wears a mural crown on coins produced in Ephesus, a characteristic of Cybele as a city protector. The round pieces covering the upper section of the Ephesian Artemis are traditionally thought to represent numerous breasts, indicating her vitality. This interpretation arose in late antiquity and culminated in the Ephesian goddess being referred to as Diana of the Ephesians, among other things. This view was based on Christian criticisms of pagan common mythology by Minucius Felix, and the current study has placed doubt on the conventional interpretation that the sculpture shows a many-breasted goddess.

Artemis Ephesus. Kharmacher, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Artemis Ephesus. Kharmacher, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The evidence reveals that the oval items were not meant to depict any aspect of the goddess’ body. The goddess’ skin has been painted black in certain replicas of the statue (presumably to mimic the old wood of the original), but her garments and regalia, including the so-called “breasts,” have been left unpainted or created in various colors. Some historians believe that the oval items, rather than breasts, were ornaments that would have been hanging ritualistically on the initial wood statue – maybe the sacs of sacrificial bulls or perhaps eggs – and were sculpted features on later versions.

Why Was the Temple of Artemis Built?

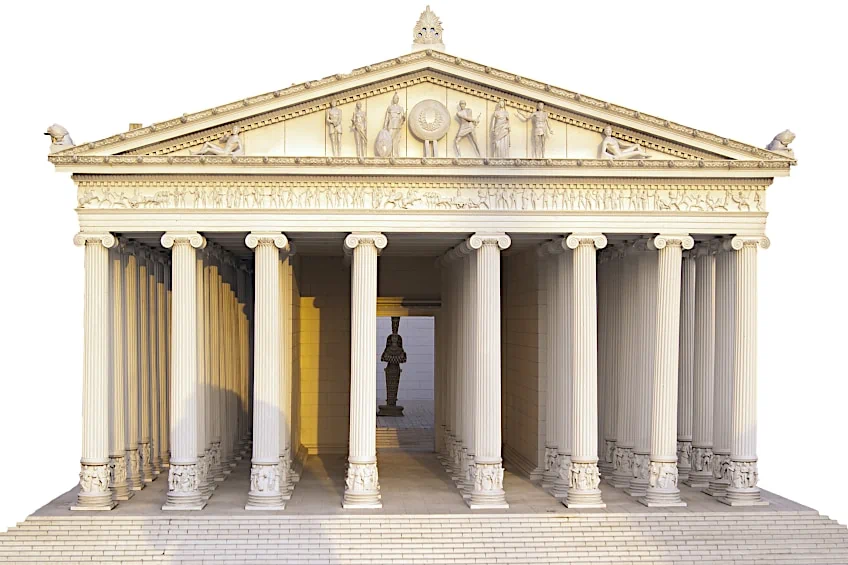

The city had tense relations with the neighboring kingdom of Lydia, surviving numerous invasions while assimilating certain cultural aspects. Around 550 BC, the Lydian king Croesus seized Ephesus and financed the development of new structures, including a huge new temple dedicated to Artemis. Many historians believe that it was the very first temple in Greece to be made from marble. Chersiphron of Knossos and his son Metagenes oversaw the construction of the remarkable Ionic temple. Many academics believe that just Chersiphron was involved. Nonetheless, Chersiphron and Metagenes are credited for writing a temple treatise in the mid-6th century BC. The structure was then completed by Paeonius of Ephesus, according to the Roman writer Vitruvius.

Croesus and Solon by Johann Georg Platzer. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Croesus and Solon by Johann Georg Platzer. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Construction of the Temple of Artemis

The temple site was inhabited as far back as the Bronze Age, with a series of earthenware artifacts dating back to the Middle Geometric period, when a peripteral sanctuary with a hardened floor made of clay was built in the later part of the 8th century BC. Ephesus’ peripteral sanctuary is the oldest representative of a peripteral form on the coast of Asia Minor, and possibly the first Greek sanctuary enclosed by colonnades worldwide. A deluge destroyed the sanctuary in the 7th century BC, leaving almost half a meter of sand on top of the temple’s clay floor.

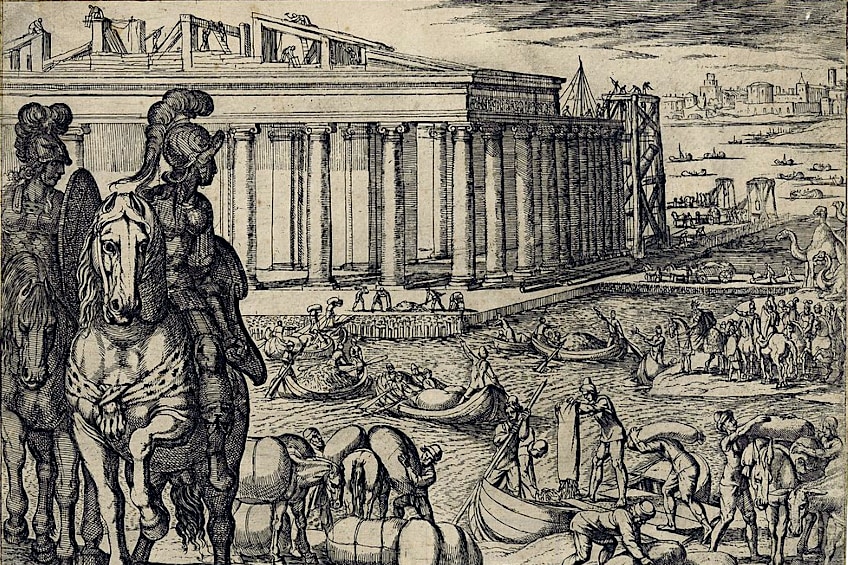

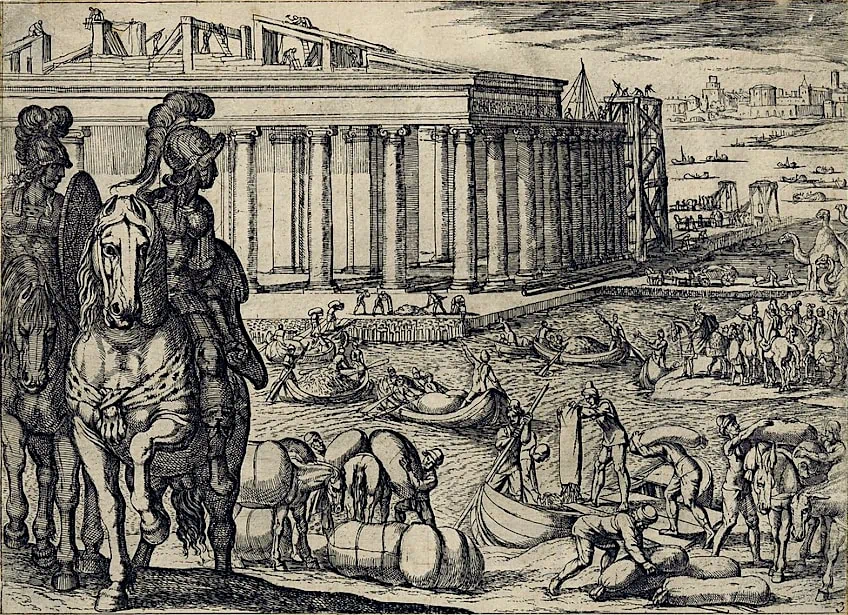

17th Century Depiction of the Construction of the Temple of Artemis. Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

17th Century Depiction of the Construction of the Temple of Artemis. Rijksmuseum, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Then, in 559 BC, Chersiphron would be ordered by Croesus to reconstruct the temple. Its columns were 13 meters in height, arranged in two rows to create a spacious ceremonial corridor surrounding the cella (“small chamber”) that contained the deity’s image. The front columns were adorned with relief images from Greek mythology. The temple’s ornamental frieze included scenarios featuring Amazons, who were said to have taken refuge from Hercules at Ephesus in Greek mythology. The architrave blocks that topped the columns are believed to have weighed 24 tons apiece, and the engineering skill that it took to set them in place prompted the Ephesians to believe it was the goddess Artemis herself who had put them there.

The cult figure of Artemis that resided within the sanctuary (and for which the entire building was erected) was fashioned of cedar wood.

The temple’s foundations have attracted some interest, beginning with Pliny the Elder, who praised the engineer Theodorus of Samos for constructing them on swampy terrain, reducing the influence of earthquakes. Pliny also mentions using alternating layers of packed charcoal and sheepskins to create the required stability to withstand the immense weight of the buildings that were going to be erected on top. Archeological digs at the site in 1870 AD revealed that the temple’s foundations were made of layers of charcoal and a mortar medium. Layers of charcoal and marble fragments have also been unearthed in 20th-century digs, but no indication of sheepskins has been detected.

Destruction of the Temple of Artemis

The temple was destroyed by fire in 356 BC. According to many versions, this was a self-aggrandizing act of arson committed by a man named Herostratus who lit the wooden roof beams in order to obtain fame at whatever expense; he subsequently became one of the most notorious arsonists in the world – his single motivation for committing the act.

Modern research has called Herostratus’ role in the temple’s devastation into doubt. According to some historians, an attacker would have required access to the timber roof framework.

Some claim that the fire was intentionally and discreetly caused by temple officials who were aware that the foundation was eroding but that they were unable to re-position it elsewhere due to religious concerns. However, this does not explain why the temple was rebuilt several times in the same spot considering the ongoing issues with the foundations. And, the arsonist’s motivations have been questioned as they were only revealed when he was being tortured which does not make sense if his intention was to become famous – he would have told them straight away rather than suffer through unnecessary physical torment. Therefore, the “arsonist” could very well just have been a scapegoat for the clergy of the temple.

Rebuilding the Temple of Diana of the Ephesians

Alexander proposed to fund the temple’s reconstruction; the Ephesians graciously declined, stating that it would be wrong for one deity to construct a monument to another, and finally reconstructed it after his passing, at their own expenses. Work began around 323 BC and lasted for several years. With almost 127 columns, this third temple was considerably bigger than the last. Endoeus was designated by Athenagoras as the sculptor of the principal cult image of Artemis. Another altar dedicated to Artemis Protothronia, and a series of figures above this altar, including an archaic representation of Nyx by the sculptor Rhoecus, are mentioned by writers from the time. Pliny recounts Scopas’ carvings of Amazons, the mythological founders of Ephesus. The temple was adorned with murals, columns decorated with silver and gold, and religious artworks by prominent Greek sculptors Pheidias (famous for his work on the Parthenon and the monumental sculpture of Zeus at Olympia), Polyclitus, Cresilas, and Phradmon.

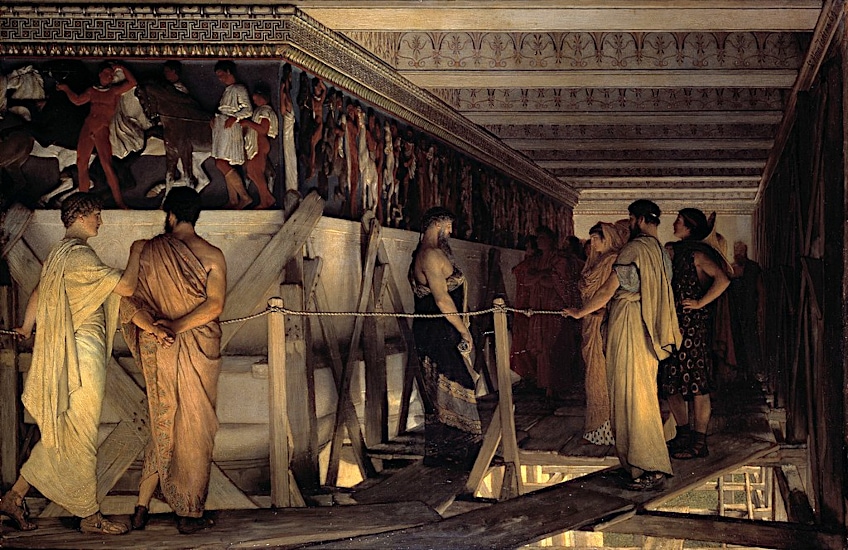

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Damage to the Rebuilt Temple

This structure lasted 600 years and is mentioned several times in ancient Christian records of Ephesus. The arrival of the first Christian missionary at Ephesus, based on the New Testament, prompted citizens to worry about the temple’s potential defilement. The story of the destruction of the temple is told in the 2nd-century Acts of John: the disciple John was praying openly in the Temple of Artemis, vanquishing its demons, when suddenly the shrine of Artemis separated into several pieces and parts of the temple collapsed, immediately converting the Ephesians, who broke down in tears, prayed, or fled. A Roman decree from 162 AD recognized the annual Ephesian festival’s significance to Artemis and formally extended it from a few holy days in March and April to an entire month, which made it one of the biggest and most spectacular religious celebrations in Ephesus’ religious calendar.

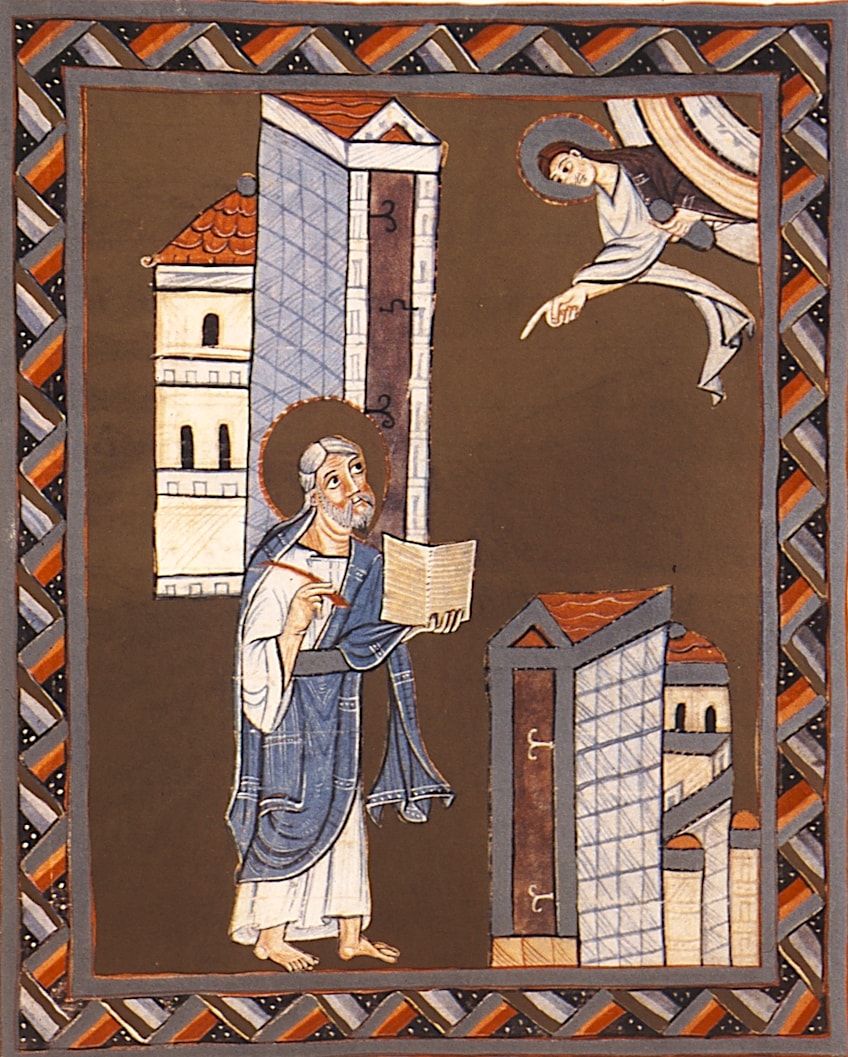

Saint John at Ephesus, Bamberg Apocalypse Folio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Saint John at Ephesus, Bamberg Apocalypse Folio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 268 AD, the Goths, led by Veduc, Respa, and Thurar, raided numerous prominent cities and burned down the famed Temple of Artemis at Ephesus. “The degree and seriousness of the devastation are unknown; the sanctuary may have stayed abandoned until its formal destruction during the eradication of pagans in the late Roman Empire. Ammonius of Alexandria mentions its destruction, maybe as early as 407 AD and no later than the mid-fifth century.

The identity of Artemis seems to have been erased by the removal of plaques throughout Ephesus when the temple was destroyed and the city became Christian.

Coin Depicting Laodicean Zeus and Ephesian Artemis. Münzkabinett Berlin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Coin Depicting Laodicean Zeus and Ephesian Artemis. Münzkabinett Berlin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Cyril of Alexandria attributed the temple’s destruction to John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, describing him as “the exterminator of devils and destructor of the temple of Diana of the Ephesians.” Proclus acknowledged John’s efforts, claiming, “In Ephesus, he desecrated the arts of Midas,” however there is little proof to back up this assertion. At least a portion of the stones from the demolished temple was utilized in the building of other structures. There is no validity to a late medieval myth that several of the columns in the Hagia Sophia were removed from the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus.

Excavation of the Temple of Artemis

The location of the temple was unearthed in 1869 by a team directed by John Turtle Wood and supported by the British Museum following six years of research, and excavations proceeded until 1874. Several more sculptural fragments were discovered during the 1904 to 1906 excavations supervised by David George Hogarth. The discovered sculptured elements from the 4th-century reconstruction, as well as a few from the previous temple that had been included in the rubble fill for the restoration, were reassembled and exhibited in the British Museum’s “Ephesus Room.” Furthermore, the museum has a portion of what is believed to be the world’s oldest hoard of coins, which was discovered in the foundations of the temple. The temple’s site, which is close to Selçuk, is now identified by a single column made of fragmentary parts unearthed there.

That concludes our look at the facts about the Temple of Artemis. The Temple of Artemis is one of the world’s seven wonders and is also the world’s oldest marble temple. The temple was planned and erected in the sixth century BC, with early work funded by Croesus, the affluent ruler of Lydia. Merchants, monarchs, and visitors visited the temple, which became a pilgrimage destination and tourist attraction. Many people paid respect to Artemis with jewelry and other valuable items. The temple was a well-respected sanctuary, a tradition associated with the Amazons who sought safety there.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Was the Temple of Artemis Built?

The temple was built on a site that had been inhabited since the Bronze Age, and it is not known for what reason it was originally built, except that it had always been dedicated to a Goddess of some sort. It was built again in 550 BC and it became a place of devotion for people of many religions from all over the world, including an Ephesian sect that venerated Cybele, the Greek Earth Mother deity. It was mostly used as the place of worship of Diana of the Ephesians, the goddess of fertility, hunting, and the forests.

How Was the Temple of Artemis Destroyed?

The official story is that a man by the name of Herostratus burnt it down. It is said that he did it purely to gain fame as an arsonist. However, this theory has been widely disputed as he only confessed to burning down the temple after intense torture. Other theories are that it was intentionally burnt down by the temple’s clergy who were aware that the temple’s foundations were collapsing.

I am deeply passionate about history and am constantly fascinated by the rich and complex stories of the past. As the editor-in-chief of learning-history.com, I have the opportunity to share this passion with a wide audience through the creation and distribution of engaging and informative content about historical events, persons, and cultures. Whether it’s through writing articles and blog posts or creating videos or podcasts, I strive to bring the past to life in a way that is both accurate and enjoyable. My expertise in history, combined with my strong writing and communication skills, allows me to effectively communicate complex historical concepts and make them accessible and interesting to a wide range of readers. I am truly grateful for the opportunity to share my love of history with others through my work on learning-history.com.